The term “Third World” emerged in the 1950s to describe nations, many of them newly independent, that did not fall into either of the two Cold War camps. But only with the publication of The Global Cold War (2005) by Odd Arne Wested, was the Third World properly situated in its Cold War context.

It is a history of how the geopolitical atmosphere dominated by the U.S.-Soviet rivalry shaped the decolonization and radicalization processes in the Global South, including Afghanistan, Vietnam, and Algeria, to name a few.

Yet, aside from the high-profile case studies of Cuba and Nicaragua, one region of the Global South has remained conspicuously absent from the recent literature inspired by this new understanding of the Third World: Latin America.

Enter into this void, and with a nod to Wested’s book, Latin America and the Global Cold War (2020).

The “fruit of a multinational, multilingual effort by fifteen scholars,” this collection of essays reexamines Latin American history from a “Third Worldist” perspective, defining the Third World as a global political project devoted to anti-imperialist liberation, sovereignty, and development.

Latin America is a vast region comprising 33 individual countries in the southern half of the Western Hemisphere. To account for the diversity of political, cultural, and economic differences, the authors offer “two conceptual halves” to explore the “various manifestations of Latin American Third Worldism” during the Cold War.

Part I, entitled “Third World Nationalism,” focuses on the utilization of anti-imperialism to serve nation-state agendas of various political colors. For example, Thomas C. Field describes how revolutionary Bolivia worked to remain the “darling of U.S. foreign policy elites” even as it sought economic resources from the Eastern socialist bloc, and Vanni Pettinà documents a similar “hybrid international position” adopted by Mexico in the 1960s and 1970s as it sought deeper diplomatic and economic ties with the Soviet Union directly through purchase of Soviet tractors.

Both Bolivia and Mexico relied on economic ties with the United States, ties often dependent on political alignment. Thus, while each exercised diplomatic freedom, they undertook actions with a constant eye to the potential consequences from their Northern neighbors.

Part II, “Third World Internationalism,” adopts a transnational approach to examine moments of “solidarity, heterogeneity, and inclusion” between non-state actors and organizations.

The first summit of the Non-Aligned Movement in Belgrade, 1961.

Both Miguel Serra Coelho and Stella Krepp examine Brazil’s application of Third Worldism, Coelho through its relations with India and Krepp through consideration of its attention to the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM). Ultimately, although Brazilian political elites gestured toward anti-colonialism, they simply “perceived themselves to be Western, both culturally and politically,” tending to support colonial powers in international forums.

Argentina under Perón provides another example of limited engagement with more internationally focused Third Worldism. As David K. Sheinin chronicles, despite the nation’s willingness to defy the trade embargo against Cuba “as a mark of Latin American unity, their shared revolutionary voice, and Third World development,” Argentina’s otherwise “tepid” approach to a third way never truly abandoned its “strong, consistent pro-United States strategic and commercial biases and interests.”

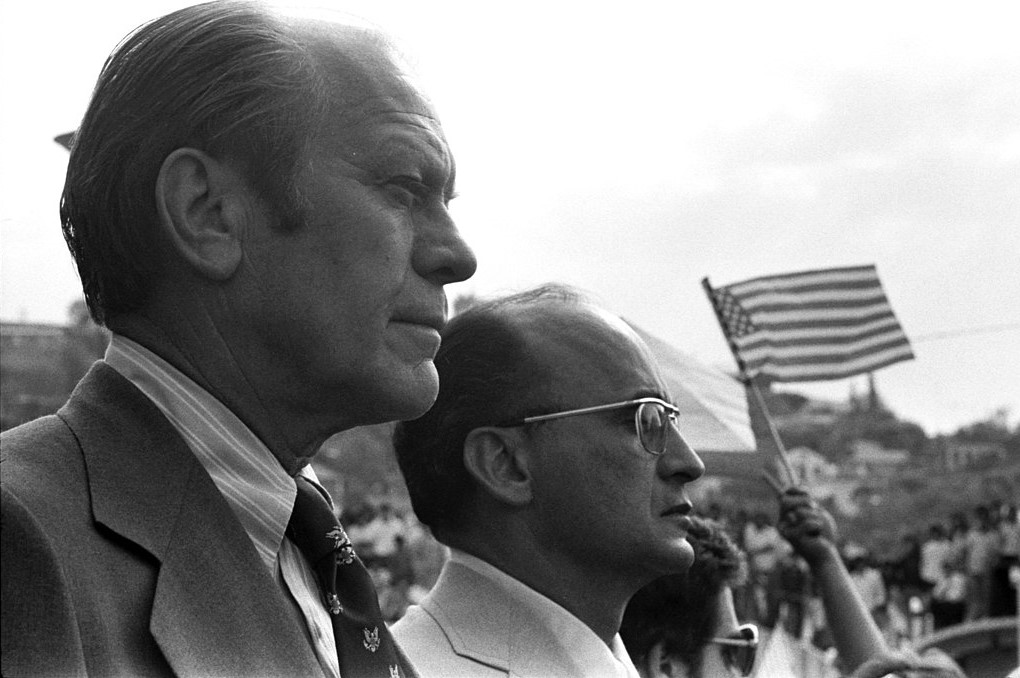

Other authors consider foreign connections forged beyond formal politics to advance nationalist agendas. Miriam Elizabeth Villanueva recounts the Panamanian military government’s efforts to complete the Torrijos-Carter Treaties that would restore its control over the Panama Canal. Not only did they deploy anti-imperialist rhetoric in the UN, the NAM, and the Organization of American States (OAS), but also collaborated with the intellectual Left to produce cinematic and performative art that would build local, regional, and global support for Panamanian liberation.

Likewise, in the late 1970s, the Nicaraguan Sandanistas appealed to an international audience to fund their efforts against President/dictator Anastasio Somoza Debayle, turning to Socialist International and Third World solidarity activists in Western Europe, as Eline Van Ommen shows.

There are some outlier essays that do not fit neatly into the “conceptual halves” set up by the editors. Essays from Alan McPherson and Christy Thorton both turn to events before the Cold War and decolonization. McPherson illustrates the transnational networks mobilized by Haitians and African Americans to oppose U.S. occupation of the island nation from 1919-1934.

Likewise, Thorton demonstrates that the adoption of the Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States in the UN was the “culmination” of decades of advocacy by Mexico dating back to its “developmental vision” first articulated during its 1910 Revolution. What, then, should the chronological bounds of Third Worldism as a political project be?

In the only essay that treats the grassroots formulation of Third Worldist identity, Sarah Foss details the National Program of Community Development undertaken in Guatemala during the 1960s, in which government-sponsored project planners deployed a Third Worldist identity to convince rural communities to buy into the existing political system rather than undertaking their own revolution. Local actors, though, recognized the political agenda of the project thanks to their international awareness, and pursued an “alternative model of development and citizenship.”

This first attempt to merge the fields of Latin American, Third World, and Cold War history points the way toward much future research. With memorable anecdotes, concise chapters, and accessible theory, there is much to discover from Latin America and the Global Cold War for professional and general readers alike.