The Guatemala inoculation experiments entailed a series of human rights violations that reminds us of the dangers involved in allowing scientific knowledge and national security to justify what the New York Times called, in 1947, “ethically impossible” actions.

Between 1946-1948, around 1,500 people in Guatemala—including prisoners, soldiers, prostitutes, psychiatric patients, and children—were enrolled without consent in unethical studies related to the testing and treatment of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) including syphilis, gonorrhea and chancroid. Among many procedures, they were intentionally infected with these diseases through sexual contact with paid prostitutes and by smearing the bacteria on open cuts and sores or inserting it in the eyes, rectum, or urethra.

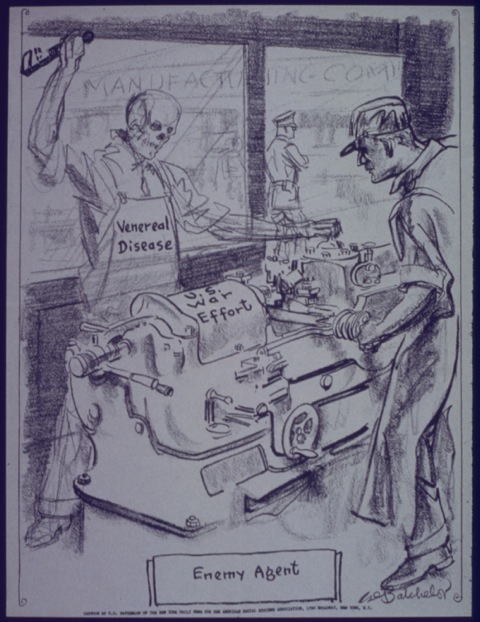

This World War Two cartoon portrayed venereal disease as dangerous to the U.S. war effort

The Guatemalan studies only fully became public when they were accidentally discovered in 2010. The U.S. National Institutes of Health and the Pan American Sanitary Bureau (which would later become the Pan American Health Organization) financed and institutionally supported the experiments. The Guatemalan government was also complicit and received compensation for its participation.

The documents discovered in 2010 revealed that Dr. John Cutler of the Public Health Service headed the Guatemalan experiments. Cutler would later be involved in the now-infamous (and more well-known) Tuskegee experiments in which hundreds of African Americans with syphilis were studied without being provided treatment for the disease.

The U.S. government’s support for the Guatemalan experiments came primarily out of its need to reduce Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) in the military. Ever since the Civil War, STIs like gonorrhea and syphilis had incapacitated large numbers of troops and resulted in the loss of significant man-hours.

During World War Two, the government launched a full campaign to educate soldiers about the dangers of “VD” (venereal disease) and prevent it through the use of condoms and “Pro Kits” (prophylactic kits). This campaign made an explicit link between unprotected sex and the nation’s security. Government propaganda emphasized the image of women as carriers of VD and of VD as a threat to the war effort.

The prevention campaign was not effective enough, however. GIs continued to contract STIs, and the government wanted to find ways to treat and cure these diseases. Originally, scientists had begun to study STI treatments in 1944 in the U.S. Penitentiary in Terre Haute, Indiana using documented consent. Yet the scientists were unable artificially to provoke infection in the prisoners. Backed by the U.S. government’s need to control VD in the military, scientists decided to move their operations out of the country—and into foreign bodies—in the hopes that they could expedite their findings.

On the left, government propaganda encouraging the use of 'Pro Kits.' On the right, government propaganda emphasizing the image of women as carriers of VD.

By moving the study to Guatemala, researchers would have the option to test and observe “naturally” infected subjects (that is, infected through sex) without the need to obtain consent.

One of the first aims of the Guatemala experiments was to better understand serological testing for syphilis. Prisoners, leprosy patients, and psychiatric patients were all tested, but because of the high rate of false positive tests, Cutler also carried out hundreds of tests on children—primarily orphans—as a way to verify the testing methods themselves. There was no documentation of consent by the children’s parents or guardians for their participation in these tests.

In order to study STI treatments, multiple rounds of “natural infection” were attempted on the Guatemalan subjects. Prostitutes were used to infect men; some of these prostitutes were deliberately infected via cervical swabs of infected pus. When this method also proved highly ineffective in provoking infection, men were infected by having pus from men with gonorrhea or syphilitic material painfully rubbed onto their genitals or into their urethras, ingesting syphilitic material, or having it injected directly into their spinal fluid.

The goal was to provoke infection in order to test the effectiveness of prophylactic treatments. Ultimately, however, only some of the infected participants received any treatment at all, and the original goal of fully testing the efficacy of prophylactic treatment was never carried through.

|

The story of the Guatemala inoculation experiments reminds us that the ethics of human subject research need to be continually re-examined and enforced (even when national security is raised as the justification). Also, they highlight that scientific inquiry must not only benefit developed regions at the expense of developing ones. As clinical trials continue to expand in regions like Latin America, ethical considerations must not only focus on consent, but also on addressing the healthcare needs of the populations where studies take place.

Over the twentieth century, the United States has put laws into place to protect human subjects in scientific research—largely inspired by outrage at the Tuskegee experiments. Nonetheless, the lesson of the need for constant vigilance is important because ethical breaches are not always as obvious as those of the Guatemala experiments.

Recently, the WHO has found that despite a marked increase in the export of Western clinical trials to Latin America, test populations there are not always ultimately able to afford or access the medications being tested. Further, in many parts of Latin America, access to healthcare is difficult or expensive. When faced with the option to participate in a clinical trial, people may sign up because of the lack of other options for possible treatments—even if they may only be receiving a placebo and even if their treatments may end when the trial concludes.

Despite advances in research and treatment for STIs, the prevalence of treatable STIs remains high in Latin America. This reflects underlying structural issues regarding access to healthcare and health information, and has serious public health implications. For example, up to 10% of pregnancies in Latin America occur in women with untreated syphilis – a condition that can lead to as many perinatal deaths as malaria or HIV. In the U.S. and northern Europe, the percentage of pregnant women testing positive for syphilis in recent years is less than half of what it is today in Latin America.

The legacy of unethical medical experiments has also led to distrust of the medical establishment. Amid the current crisis surrounding the Zika virus, Guatemalan citizens do not know where to turn for information and do not have access to adequate healthcare services for testing and treatment.