From the Editors: 2014 was a year of tremendous and unfinished change for Ukraine: a dramatic political revolution in Kyiv's Independence (Maidan) Square and the overthrow of President Viktor Yanukovych, the surprise annexation of Crimea into Russia, ongoing fighting in the eastern regions of Ukraine, and rising tensions between Russia and the United States/European Union that are reminiscent of the darkest of Cold War days.

Andriy Lyubka sends us a postcard from Kyiv about the emotional and spiritual fallout of the events of 2014. Born in 1987, Lyubka is a poet, essayist, and prose fiction writer who lives in Uzhhorod, Ukraine. He spent much of December 2013 on Kyiv’s Maidan Square and has been writing about political events in Ukraine ever since.

|

| Riot police officers in Kyiv, December 2013 |

The year 2014 will no doubt become a caesura, a line dividing Ukraine’s history into "before" and "after," dividing society into the generation of participants of Maidan and the next generation that will enjoy the fruits of either our success or defeat.

More than that, though, 2014 erects a wall between supporters and opponents of Maidan. In other words, we find ourselves in a situation where we cannot even enjoy our victory there. Because people died, people who in the critical moment, with wooden boards as their shields, intentionally faced bullets.

The German philosopher Karl Jaspers posed a similar question after World War II. He was a critic of National Socialism at the dawn of Hitler's career. In particular, he strongly criticized the Reich Concordat with the Vatican in ‘33 and the Olympic Games in Berlin in ‘36. No wonder the Nazis quickly "asked" him to leave the university and banned him from publishing. Moreover, his wife Gertrude Jaspers was Jewish, so the philosopher initially was advised to divorce her, and after he refused, the couple was in jeopardy of deportation and death.

Despite all this, Jaspers and his wife continued to live in Nazi Germany and survived Hitler's regime. Most likely, they were not killed because of the philosopher’s worldwide fame, but Karl didn’t count on it; he made sure to get ahold of cyanide. He and Gertrude decided to commit suicide if they heard the “rap.” But no one knocked on their door. And in 1945-46, Karl Jaspers wrote a brief and brilliant essay – "The question of guilt."

|

| Protestors clashed with security forces in Kyiv, often coming to resemble a war zone more than mere protests. |

In the text, the philosopher distinguishes between four kinds of guilt, the last of which is metaphysical guilt. This guilt is felt by people who have not committed any crime or sin, but who managed to survive the tragedy of the Second World War. It is not only that these people did not fight Nazism, voted for the Nazis in the elections, did not go to protest demonstrations. They might even have helped others, hid Jews or misled the SS; but the guilt exists in the fact that they have survived in a situation where others did not.

Jaspers diagnosed an ailment of a generation of people: why did I survive when others died? Maybe I'm more base, more cunning, a bigger coward? Why did I live and they die?

After January and February 2014, Ukrainians asked themselves the same question.

People who understand the phenomenon of Central and Eastern Europe predicted long before the Revolution that everything would end in blood – that is the rule in this part of the world. However, this bloodiness might have had a political face – for example, in Armenia the shooting took place inside Parliament. In Ukraine, unfortunately, it was not high-level politicians, but ordinary citizens who died on Maidan, after failing to achieve any specific gains for EuroMaidan.

|

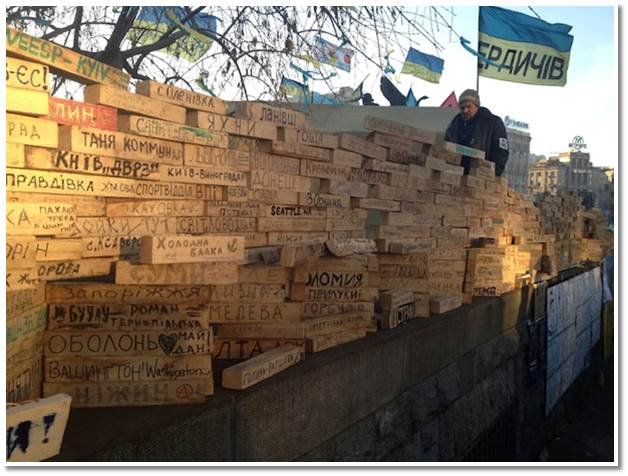

| Hundreds of city names on woodblocks, created in support of EuroMaidan. Photo by Rudy Hightower, December 2013 |

It was pure self-sacrifice, not only in the name of patriotism, but also self-respect: If I’m already here, there is no retreat back to the street. They were not only swept up in patriotic fervor, but - just as importantly – they were ashamed to return home humiliated. That's why the makeshift boards with printed photographs of the Heavenly Hundreds in every district center are so impressive – look at us, ordinary people who might have not died, who might have chosen to conform, or not to have been present at Maidan.

And now many Ukrainians ask themselves: why am I alive, why did I not appear there at that moment? Why does this writer write these words now, where was he at the most critical moment? You can find hundreds of rational arguments to justify, but the nature of metaphysical guilt is that it does not accept any excuses or explanations. It just burns.

|

| EuroMaidan Protests in Ukraine, December 2013 |

It is not necessary to be a distinguished German philosopher, with his fame, or even a German to suffer metaphysical guilt. Lydia Ostalovska in her book "Watercolors" describes the life of Jewish immigrants from Europe to their new homeland – Israel.

There they felt as though they were back in the ghetto; other Jews shunned them and couldn’t understand how millions voluntarily went to the gas chambers. Why did not they revolt, why didn’t they fight, why did they shame the whole Jewish nation? And so as a result European Jews found themselves marginalized – they lived in separate areas, no one spoke with them, no one wanted to marry their children, and the children themselves tried to escape their parents as quickly as possible.

As you see, it is not necessary to belong to the nation of executioners to suffer; nations of victims have the same guilt.

|

| EuroMaidan Protests in Ukraine, December 2013 |

This is especially true after the annexation of Crimea by Russia. Maybe it is for the best that we got rid of that region, like dropping ballast, but the way we lost the peninsula will be a trauma for an entire generation.

Adam Michnik, commenting on annexation, said: "The Poles would definitely have fought back." How will we live with the fact that Ukraine did not resist? How can we not to associate this with our age-old complex of victimhood which keeps us from finding our way in life? What will we answer in a few years, when children want to know about 2014 and ask, "Why did Ukraine surrender without a fight?"

Of course, there are hundreds of excuses and arguments, but metaphysical guilt does not recognize them. It merely burns.

|

| Protestors throw Molotov cocktails in direction of Interior Ministry Police. EuroMaidan Protests, January 2014 |

It burns individual people and it burns for society as a whole. I wish I could write that progress and victories – building a proper Ukraine, for example, in the name of the victims, the Heavenly Hundreds – will stifle the pain and memories. I would like to believe this argument, this method of renewal. But metaphysical guilt does not recognize it. Instead, it burns.

This article appeared originally in Ukrainian in the Kiev Times. Translation by Angela Brintlinger.