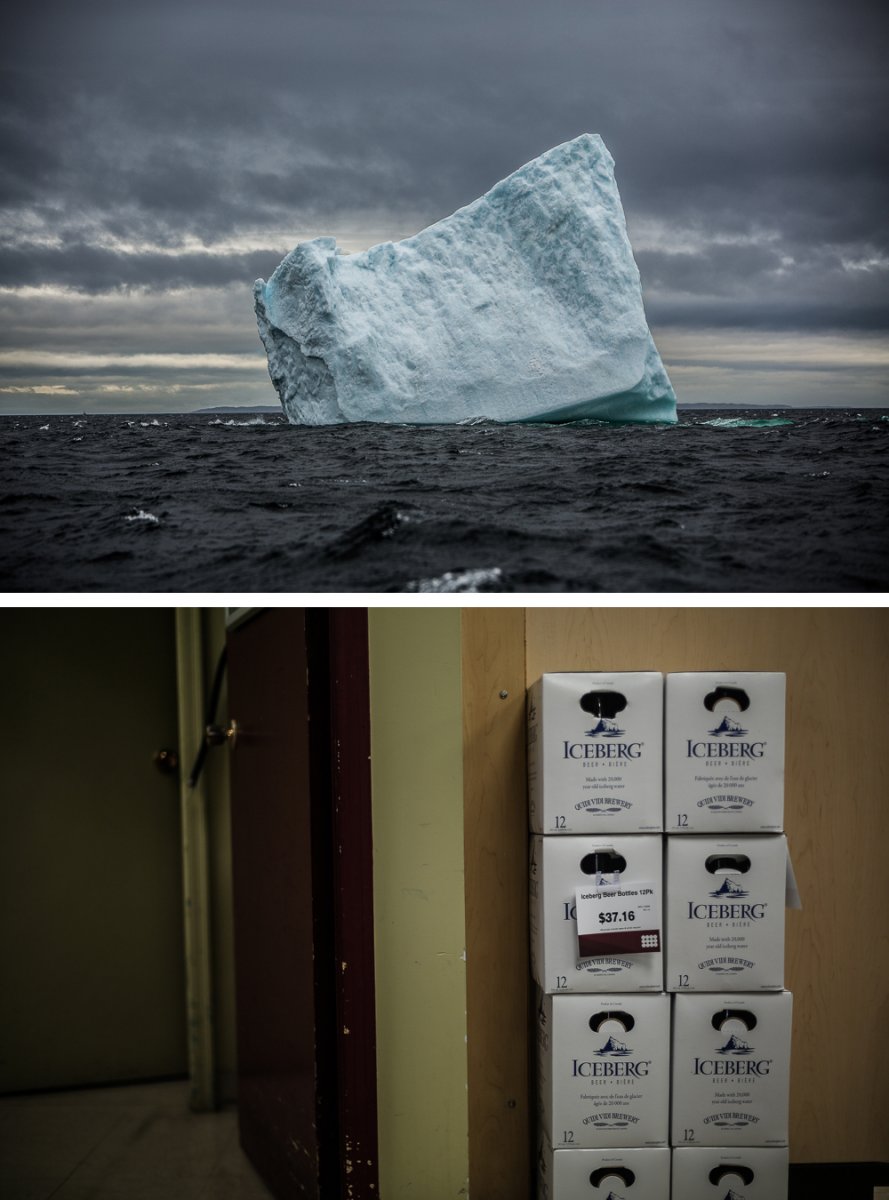

Iceberg, St. Lunaire.

In 1497, Venetian explorer John Cabot declared that the waters off the coast Newfoundland were so rich with cod that "fish that can be taken not only with nets but with fishing-baskets." I know this because this story, in various forms, was relayed to me by everyone from a museum docent to a checkout clerk. For nearly 500 years, Spanish, English, Portuguese, Basque, French, Irish, Celtic, and Scandinavian fisherman joined Indigenous people in harvesting sea life off the banks of what would become Canada’s eastern shore. Cod—so synonymous with fishing that it became known simply as “fish”—was such an integral part of life in Newfoundland that one anonymous source in the early 20th century declared that “Fish is everything. Without it, we are nothing. It is responsible for our culture, our music, our architecture, everything.”

Two events in twentieth century changed that. First, between 1950 and 1977 the Canadian government instituted a program of resettlement whereby residents of more than 1,300 small, self-sufficient villages on the coast were relocated to more centralized communities. It was argued that infrastructure projects such as road-building and electrification, as well as education and health services were impossible to provide to such disparate outports. The only way to bring Newfoundland into the cash-based economy with the rest of Canada was to create larger communities. Resettlement shattered the small-village life that revolved around fishing and communal agriculture.

A final blow came in July of 1992 when the Canadian government imposed a moratorium on the Northern Cod fisheries. After years of overfishing, the Northern Cod biomass had fallen to 1% of what it had been earlier in the century and the moratorium was viewed as the only way to save the industry. While the cod have rebounded some, these two events effectively ended Newfoundlander’s economic relationship with fish.

What do a people do when all the stories they tell about themselves are no longer valid?

This problem is not unique to Newfoundland. Hazard County, Kentucky; Youngstown, Ohio; Detroit, Michigan: residents of all of these places are figuring out how to tell new stories about themselves. Yet the singularity of the stories Newfoundlanders tell about their past reveals its discrepancy with their lived landscape in a unique way.

These photographic diptychs from summer 2017 highlight these struggles as Newfoundlanders try to figure out what stories they want to tell.

Cradled fishing boat, Parson's Pond (top); Oil rig, Bay Bulls (bottom).

Painted rock, Bonavista Peninsula (top); Avalon Wilderness Reserve, Avalon Peninsula (bottom).

Lighthouse, Trinity (top); Lighthouse, Twillingate (bottom).

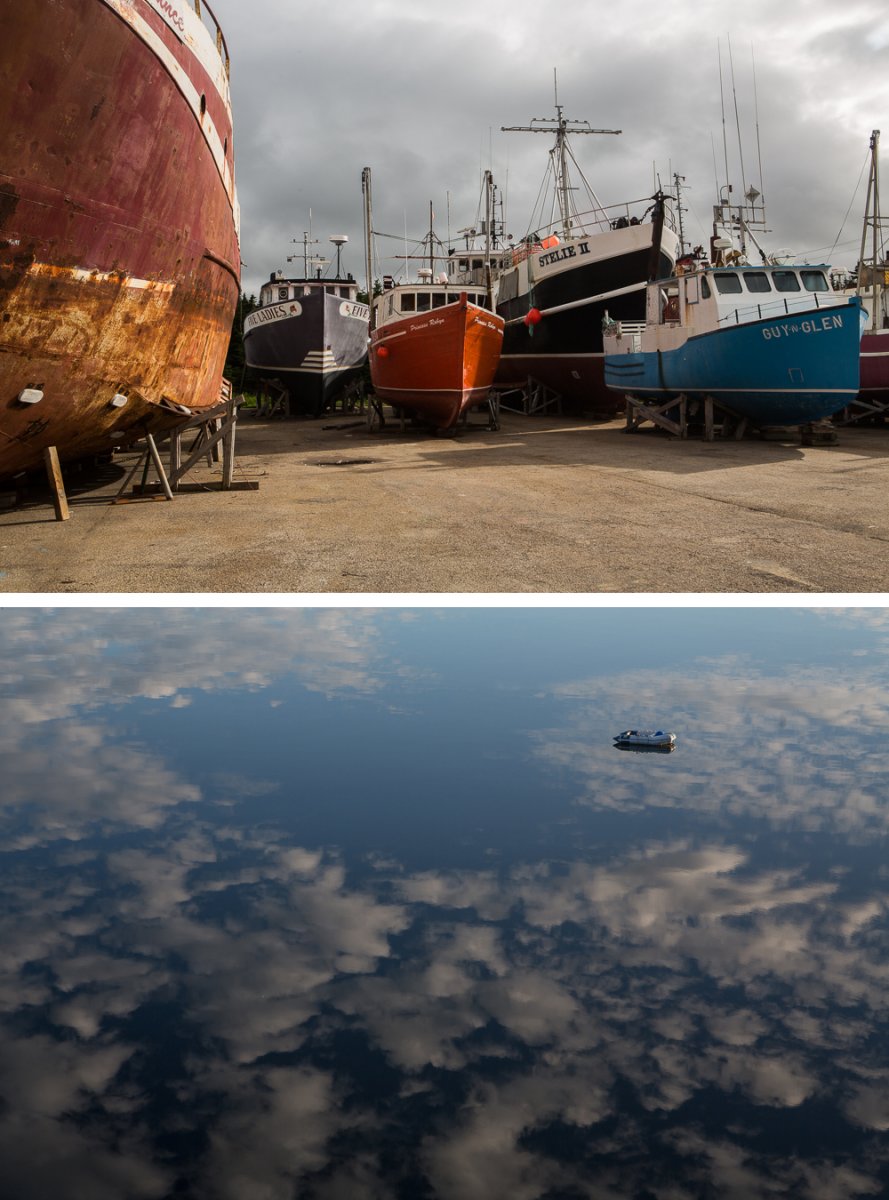

Cradled fishing boats, Port Saunders (top); Dinghy, Dunfield (bottom).

Clothesline, Avalon Peninsula (top); Fishing shacks, Northern Peninsula (bottom).

Camper, Back Harbor (top); Dusk, Trinity (bottom).

Iceberg, St. Lunaire (top); Iceberg, Placentia (bottom).

"The Trouting Newfoundlander", Duntara.

Upside-down boat, Northern Peninsula (top); Upside-down car and fishing shack, Northern Peninsula (bottom).

Fishing boats with crow, Parson's Pond (top); River of Boats model boats, Witless Bay (bottom).

House with model of itself, Twillingate (top); Three mobile homes, Job's Cove (bottom).

Jellybean guest houses, St. Anthony (top); Jellybean rocks, Birchy Cove (bottom).

Bench at World Heritage site, L'Ans aux Meadow (top); Church, Duntara (bottom).

Newtown Anglican Church (top); Power lines, Avalon Peninsula (bottom).

Clouds in Placentia Bay (top); Lighthouse-keepers house, River of Ponds (bottom).

This Postcard is an adaptation of David Bernstein's "The Stories We Tell: Newfoundland": http://www.davidbernsteinphotographer.com/the-stories-we-tell-newfoundland/

[All photos by author.]