I stand at the bow of the ferry as the water of the White Sea comes in wave after wave through the hole in the gunwale for the anchor chain. Stepping up on the coiled ropes lying on the deck, my feet stay dry and I look out with excitement at the outstretched sea in front of me. The weather could not be more perfect—sun, light winds, calm seas, easy sailing across a Sea known for its nausea-inducing swells.

A mother and son play in the running water beside me while a young couple stands draped over each other. A middle-aged man discusses cameras with a young photographer taking “art” photos.

And then, about an hour and half into the trip, we all see it. The Solovetskii islands (a.k.a. Solovki) and the spires of its amazing Monastery complex appear on the distant horizon.

First Sighting: The Solovetskii Islands (a.k.a. Solovki) and the Solovetskii Monastery as they come into view from the ferry.

Coming Closer: The Solovetskii Monastery as the ferry enters the harbor.

I marvel at the approaching human and environmental wonder of Russia’s Solovetskii Islands—an archipelago of six major islands (and about 100 smaller ones) in the White Sea not far to the south of the Arctic Circle. A center of Russian Orthodoxy for centuries, the islands are a Russian national park and have been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1992.

Map of the White Sea and Solovetskii Islands (Solovki) in Russia.

A Bit about the Islands

People have come to Solovki for thousands of years, but it wasn’t until the late 15th century that humans began to live full-time on the island.

For centuries, fishermen would take boats to the islands in the summer months to take advantage of the rich fishing in the waters nearby. When winter came they would return to their homes on the mainland with fish aplenty for the long, cold months ahead. These pre-historic fishers have left behind amazing stone constructions: labyrinths and burial mounds.

In 1429, the first two permanent settlers on the island were Orthodox monks—Savvatii and German. They sought out the islands not for the fish but for solitude; to be able to worship God more fully without any of the distractions of humanity.

The Solovetskii islands were hardly an easy place to live, and Savvatii was an old man. But they sought the most distant point imaginable where they might live an ascetic life. They searched for a place where they could pray and work without interruption, and where the forces of nature and the cold climate would test their spirits and their bodies each day.

A Diverse Landscape: The forest on Solovki (left), and the tundra-like landscape of Big Zayatskii Island (right).

While I stood comfortably on the ferry as it plowed the waters to Solovki, I couldn’t stop thinking that these two men so many centuries before had rowed out across the sea to an island they had never seen before to start a life as distant from other people and as physically grueling as possible.

The historian Roy Robson who has written a marvelous book on Solovki asks, “What would make someone leave life behind, seeking an existence of unremitting toil and prayer, where sleep and food were considered weaknesses of the flesh.” What indeed?

In one of the great paradoxes, word spread quickly of the holiness of these two men and soon others wished to join them or live nearby, to learn from them and their ascetic life. And so began one of the great struggles of the religious community on Solovki: whether to search for complete isolation so better to pray and to live a godly life of renunciation or to share and spread the asceticism and to build a larger religious community.

As the years passed, the monks on Solovki labored with the question of how best to serve God. In the end, it was the latter view that won the day. And one of the most glorious monasteries exists now as a result.

View of the Solovetskii Monastery.

The Solovetskii Monastery's massive stone walls were initially built stone on stone without any bonding between them. A beautiful rearranging of nature for human needs.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the monastery expanded rapidly. It attracted more and more monks, and more and more pilgrims. There were ups and downs to be sure (especially during the great Russian religious Schism of the 17th century, when the monastery was at war with the Orthodox Church). But, the monastery grew, becoming one of the most impressive monastic complexes in the Orthodox world. A spiritual center for generations, it also became one of the most economically successful ventures in the region—especially through the sustainable and immensely profitable fishing industry.

And then in the 1920s and 1930s, the monastery became the stage for one of the darkest stories of the 20th century: the GULAG–the Soviet prison system. Today it is a working monastery once again, a destination for large numbers of pilgrims and tourists alike.

Solovetskii Monastery: Sunset across the harbor.

Labyrinths

I’ve spent my career studying and teaching modern history—events and processes from the 16th century on and especially after the mid-eighteenth century when industrial change began.

Yet, as I travel, I find myself ever more fascinated by the creations and constructions that were erected by humans thousands of years ago. Standing at Stonehenge earlier this summer, I was amazed at the thought and care (not to mention muscle power) that it took to conceive and build the complex.

These stone monuments to human ingenuity and vision—like the menhirs in Brittany (France) or the native mounds in Ohio, not to mention the pyramids and Valley of the Kings and Queens in Egypt, Gobekli Tepe in Turkey, and any number of sites in Australia, China, India, and Central America—are a reminder that human history is so much longer than we usually care to remember; that our current industrial moment in the human story is just a tiny sliver in the longer run of homo sapiens on the planet.

Of course, we may never know how humans in the past built these amazing structures, or perhaps more importantly, why.

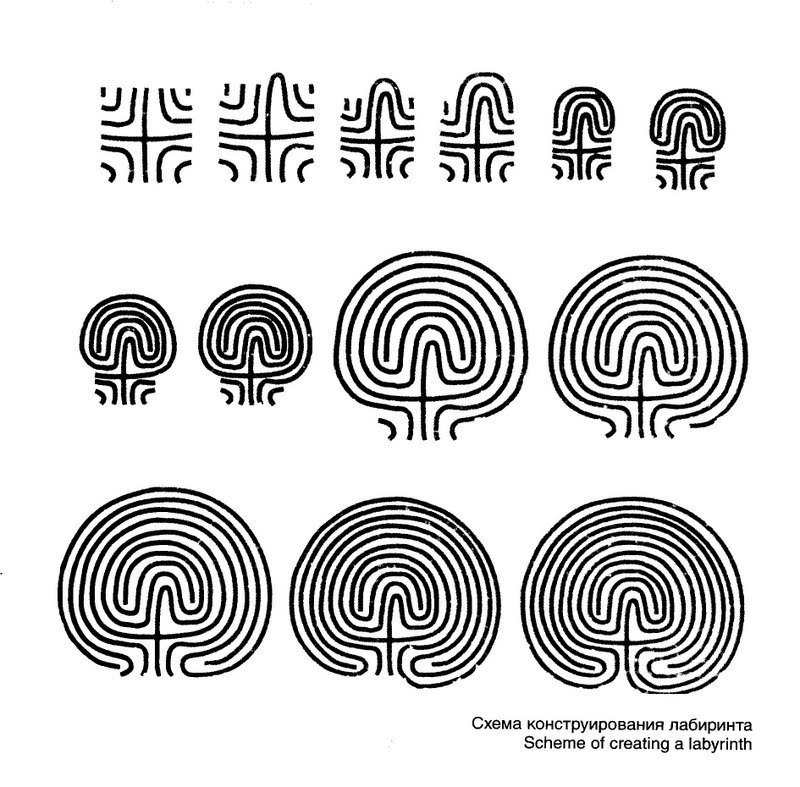

Solovki offers its own prehistoric stone structures. On the Zayatskii islands, there are some 20 labyrinths and about 900 stone piles and funeral mounds.

While no two of these fascinating labyrinths are the same design, they are usually spiral figures with a system of intricate paths lined with stones. They were made, it appears, by first tracing the patterns in the dirt and then placing the stones along the sketched designs. The largest of the labyrinths has almost 5000 stones. The stones are now covered in plant growth that shows off the circular patterns.

A view of the labyrinths.

A view of the labyrinths.

Diagram of the labyrinth designs of Solovki.

No one knows for sure what they were for or why they were built. But, there they are nonetheless, challenging us today to wrap our insufficient brains around what fishing communities in the first millennium before the Common Era might have been thinking as they took time out of their days to move these stones into concentric shapes.

Some have argued that they were designed as part of the fishing experience. That fisherman began the fishing season by walking through the labyrinth to the center. The hope was to help the fisherman find his way to an abundant catch and then return from the sea safely.

For others, the fact that the labyrinths are so close to burial mounds indicates that these labyrinths were somehow connected to the spiritual world; and the circular paths were the paths that a spirit would walk to make it to the spiritual world.

Near the burial mounds is a much more recent layout of stones: a cross laid out near the burial mounds in an effort to consecrate and Christianize what the monks saw was an unacceptably pagan site.

Christianizing the Labyrinths: Cross of stones on Big Zayatskii Island.

It is of course not unusual in Christian history for priests and others to erect crosses or paint/draw on crosses over prehistoric sites in an effort to consecrate them.

But, I was struck at Big Zayatskii Island how the priests had laid out stones to materially endow the place with specific meanings—just as the people before them. The shapes may have been different—crosses versus labyrinths—but the effort to use stones for cultural and religious purposes remained in many ways constant, reflecting the similar building materials these people—separated by so many centuries—found available for their purposes on the island.

That the cross and the labyrinths have both similarly been covered over in plant growth reflects— Ozymandias style—the way that the best laid plans and aspirations of humans disappear, collapse, or are engulfed over time.

More recently, larger, standing wood crosses have been erected on the shores.

Cross on shores of Big Zayatskii Island.

Our Ever Changing World

On Solovki, I’m reminded at every turn of the ever-changing, ever-shifting world in which we live. Even the rock under our feet is not always as solid and sedentary as we like to believe.

It is now centuries since the last glaciers retreated from atop the geological formations that now make up the Solovetskii islands. Yet, the effect of the glaciers is still being felt.

As in many places, the weight of the glaciers compressed the stone of the islands. When the glaciers receded, the islands have been experiencing a rebound effect, rising ever so slowly as the weight of the ice no longer holds them down. As a result, the islands are getting, bit by bit, a little higher out of the water. (And scientists talk about this phenomenon with Greenland, as the ice cover melts away there, freed from the weight, Greenland will rise up.)

Now, you can’t see or feel this rise day-to-day, but you can see its effects on things that humans have built.

When Russians built a church on the Big Zayatskii Island, they also built a little harbor of stone walls for boats to weather storms. Once there were five slips for boats, but today the island has rebounded to the point that there is but a trickle of water that runs through the entry way. The picture below shows the now-narrow entry way to the harbor and the berths for the boats, outlined in stone, are now dry land.

Old harbor on Big Zayatskii Island.

It’s a reminder that as we plan for our future on this planet, we have to plan for change: in the climate, in the flora and fauna, and in the landscapes and geologies we move on. Change, Solovki reminds us, is as constant in the non-human world as the human.

Lakes and Canals

I was glad I chose to rent the high-performance mountain bike as I bounced my way up the roads of the main island to spend an afternoon rowing, paddling, and otherwise exploring the remarkable system of lakes and canals that run through the island. This was one of the most beautiful and peaceful systems of water I’d been to in years, spreading a calm serenity through me each time I pulled with the oars.

At the boat rental dock, the young man handed me two oars and a paddle. “Why all three,” I asked, cursing yet again that I only had two arms. The oars were for rowing the lakes, the paddle for the narrow canals. “Lifejacket?” I inquired. “As you like,” he shrugged.

There are no rivers on Solovki, but there are some 500 lakes that fill high each spring from the melting snow and overflow. The waters then run overland from one lake to another.

The Sacred Lake providing fresh water storage for the Monastery.

If the White Sea offered the monks a seemingly endless bounty of fish to eat, they had to work a little harder to ensure fresh water for their communities. And they did so through extensive hydrological engineering systems that connected the different lakes together to provide both fresh water and also water transport possibilities up and down the island. (Even today, plying the water in a small rowboat was much more pleasant than bumping my away along the roads on bike).

Over the course of the 15th to 19th centuries, some 20 lake-canal systems were developed across the archipelago.

As the first parts of the monastery complex were being built in the 14th century, the monks needed to ensure a constant supply of potable, fresh water. They dug out a lake on one side of the monastery to capture water and then filled that lake with water that flowed down island in canals dug through the forests.

The water was then channeled in pipes and other water transport systems into the monastery (where a water wheel for milling was eventually set up, and where a collection tank was kept to ensure water in times of attack). The water then went back out through a weir to the harbor and sea.

Eventually, the system of lakes and rivers that flowed down into the Sacred Lake next to the monastery connected 70 lakes and canals up the island.

The system worked well. It ensured that the collected water didn’t sit stagnant but moved through the mill canal, powering the wheels, and then out to the harbor.

The hydrological works of the monks are a reminder to those of us accustomed to water appearing as if by magic from a tap that extended effort was so often needed to ensure sufficient, usable water available for communities. Great physical effort reconfigured landscapes and waterways to meet the monastery’s needs.

Perhaps most remarkable for me as I paddled along were the canals between the lakes that the monks built in the early 20th century for transportation purposes.

Over the years, the monks had watched the natural flows of water when the lakes overflowed in the spring. And, when they decided to carve connector canals between the lakes, they followed these paths of least water resistance.

A view of a stone-lined canal, Solovki.

A view of a stone-lined canal, Solovki.

And the canals were a marvel. The monks dug them out to allow row boats and small steam powered boats to go through. They lined the banks of the canals with large stones. And they built underwater wood and stone foundations to keep the canals open and navigable.

They were both form and function. Boats could now navigate their ways up and down the islands through the lakes. And fresh water would be in uninterrupted supply. The canals also created tree-covered aqua-pathways. As I paddled through I felt a certain warm embrace of the trees and green shores on either side.

The Botanical Gardens

In addition to the Canals and the Monastery complex, perhaps the most marvelous site on the islands was the Botanical Garden, about four kilometers from the main village.

The trees and flowers of the Botanical Gardens, Solovki.

Founded in 1822 by Archimandrite Makarii, the Gardens are located in a little ravine-valley that produces its own micro-climate (a micro-climate within the micro-climates that are Solovki). Here, the walls of the ravine block out the wind and the temperature during the year is warmer than other parts of the island.

This micro-climate allowed the monks to be able to grow all sorts of plants and trees that were non-native to the region and would otherwise be unable to survive such a northern location. Here, both monks and others experimented with what sorts of plants and trees might grow there, and learned a great deal about the effects of temperature, latitude, wind, water, and other factors on the growth patterns of this flora.

Visitors stroll in the Botanical Gardens, Solovki.

The monks grew all sorts of medicinal herbs and plants, which they sold on the mainland. They also planted trees from different parts of the Russian empire. Some trees that grew out of the protective shield of the valley had their tops knocked off again and again. A lovely tree-lined pathway was planted, but too close together and the branches grow primarily to the outside of the alley.

A tree with wind-damage and re-growth of two trunks (left), and the path of the Botanical Gardens, with branches mostly facing out because the trees were too closely planted together (right).

Some photos of the gardens. Still very active. Very unusual flowers for that far north!

Botanical Gardens. Solovki.

Botanical Gardens. Solovki.

The Gulag Prison Camp

I have taught the history of the GULAG—the forced prison system of the Soviet Union—for many years now. And as many of my students will attest, I often have a hard time getting through the discussion without tears in my eyes. For all the years I’ve studied the past and wrestled with what it means to be human, I’ve never quite come to terms with the horrifyingly deep capacity of humans to unleash terrible and unspeakable cruelty on others. We are gluttons for our doom, and particular gluttons for the doom of others.

Yet, for all the years teaching and reading about the Gulag, I had never actually visited the site of one. I’d seen prisons but never a camp. And I was intrigued to be there to feel it and sense it.

Solovki plays a special role in what Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn famously called the “Gulag Archipelago.” It was in many ways at Solovki that the Gulag got its start and also began its horrifying expansion. It was also at Solovki that the idea filtered into the minds of certain members of the Soviet leadership that the camps could be economically profitable. They never were, but the idea of profit from penal labor was held tightly and ever hopefully.

The monastery was shut in 1920—not an unexpected decision from the atheist Soviet state. But then what to do with the marvelous buildings and infrastructure?

The monastery had been used for centuries as a place of banishment and exile for opponents to the tsarist regime and to the Orthodox Church—and some prisoners had lived for decades cramped into tiny, dark, stone cells. There had never been that many prisoners, and the prison function was always a minor part of the larger monastic religious purpose. However, it set a precedent and it was not a huge leap of imagination to turn the entire monastic complex on a distant island into a prison camp.

In 1923, Solovetskii Monastery became known as the Solovetskii Camp of Special Importance (SLON in its Russian acronym, a word that means “elephant” in Russian. There were endless plays on words.)

The camp saw some 80,000 people come to it, about half of whom perished there and are now part of the Solovki ecosystem. [There are archeological digs going on in the mass graves—but I noted that the tour guide was uninterested in taking us there.]

The types of prisoners that came to Solovki tended to be elite ones: political opponents of the Bolsheviks (especially members of other socialist parties), former tsarist nobles, officers of the Imperial Army or White Army that fought the Bolsheviks in the Civil War, and Russian intellectuals and cultural icons. In the words of one tour guide: “the very light of the Russian nation.”

And they were horribly mistreated. The savagery of humanity was once again on nauseating display. Who would do these things, I kept asking myself, and how can we avoid a repeat? (And just how naïve a question is that?)

Daily life was extraordinarily hard and abusive. Cold, poorly clothed (if clothed at all), they were jammed into cells to sleep and then marched through the islands to carry out various forms of work (logging in particular) with insufficient food and clothing and broken, inappropriate tools.

On Sekirka, one of the hills of Solovki, a Church stood (with a lighthouse on top) and during the Gulag period it was used as a place of special punishment.

The church and lighthouse on Sekirka.

As historian Roy Robson describes in his book: “there, men were made to sit perfectly still atop the “perch” or “pole”—about an arm’s width wide—for hours on end, stripped almost naked, teetering on the high-ceilinged, unheated Church of the Beheading of St. John. Though they shivered and caught frostbite, the slightest movement was reason for falling off and a beating. At night, the prisoners lay three or four atop another, hoping to stay warm.”

Savage creatures we humans are. And there are so many hundreds more of these cruel stories.

Dead or almost dead bodies were strapped to a log and sent careening down the staircase on the far side of the hill. 365 stairs to the bottom.

Pilgrim stairs, Gulag stairs: Looking down Sekirka, Solovki.

Ironically, these stairs had long before had a different meaning. They were the way that pilgrims would walk up to the Church, and the word was that for every step one walked up a sin was forgiven. With the Gulag, it was the world turned upside down.

Here too the human-nature relationship was transformed. The cold climate, geographic location, and very physical characteristics that had kept humans from the islands for so long (and had made the archipelago such a good place for monks seeking solitude and fortitude) met up with human aspirations to punish and torture those who might challenge the dominant political ideology. Over the centuries, people had come for fish and in search of God. Now they came because they were arrested and forced. Now they were forced to come to endure the pain that Solovki’s nature—manipulated by humans—might unleash on other humans.

I went to see Sekirka with a group of Russian tourists, and it was fascinating to watch them as they came face to face with the terrors of their history. All peoples and countries have moments of horror in their history, where violence and cruelty saturated society. We humans share this tendency. What is different is how we then deal with the memories and the legacies of the cruelty, and how we make amends.

Pilgrim stairs, Gulag stairs. Looking up Sekirka, Solovki.

The guide spared no horrible detail for the group. And there were tears all around as she told story after story of torture and the wanton brutalization of some humans by others. I don’t know what these tourists knew or didn’t know about the Gulag and Solovki before arriving, but they left with their souls weighed heavy by the knowledge.

Interestingly, the tour guide never discussed any details about the Gulag system that didn’t directly relate to Solovki. So, any sense of the larger political context wasn’t discussed—of the Bolshevik efforts to hold power, later of Stalin, the purges, collectivization, forced deportations, or of the larger Gulag system that stretched across the whole Eurasian landmass.

The focus here was only local; on the terrifying treatment of the people who came to Solovki between 1923 and 1939.

But perhaps that was enough.

[All photos by Nicholas Breyfogle, 2013]

My visit to the Solovetskii Islands was funded by the Leverhulme Trust, https://www.leverhulme.ac.uk/, and was part of a larger project on Russian environmental history https://www.york.ac.uk/news-and-events/features/russian-environmental-history/