We take off our shoes and coats and send them through the X-ray machine with our laptops (separate bins, please), while subjecting ourselves to a full body-scan. Airline passengers in the United States have come to expect these kinds of security measures as a guarantee that their flight will be safe, in the wake of the 9/11 terrorists attacks and subsequent threats in the 21st century.

The FAA is sometimes called a “tombstone agency”: change only comes after a death —and usually only after a large number of deaths. The reactive nature of the FAA continues today, with many criticizing its failure to prevent the crash of two Boeing 737 MAX aircrafts and the loss of nearly 350 lives. Yet this pattern of commercial aviation disasters triggering the subsequent enactment of safety measures dates back the early 1930s. As a result of each of these ten tragedies, commercial aviation really is safer today than it was in the past.

1. The “Knute Rockne” Crash, 1931

An advertisement for the 1940 film Knute Rockne, All American (left). The remains of the crash of TWA Flight 5 in 1931 [Photo from the Kansas Historical Society] (right).

There had been many air crashes before, but none seemed to catch the attention of the American public as much as the one that killed legendary Notre Dame football coach Knute Rockne. On March 31, 1931, Transcontinental and Western Airlines Flight 5 took off from Kansas City, MO for Los Angeles, CA. Before it reached its scheduled stop in Wichita, KS, however, it crashed near the small town of Bazaar, KS. All eight persons on board perished.

The crash received extensive media coverage and the public demanded answers. Investigators arriving at the scene had their job made more difficult by souvenir hunters who had stripped the wreckage of the Fokker F10, leaving behind only the engine, propeller, and wings. Investigators determined that the airplane wing, made of laminated wood, had failed in flight. Moisture had weakened the glue that held it together. In response, the Bureau of Air Commerce grounded all Fokker F-10s.

Prior to the so-called “Rockne Crash,” the results of accident investigations were not released to the public. Afterwards, the Bureau publicly released all accident reports. The Bureau also increased the number and kind of inspections commercial aircraft needed to be deemed airworthy. With the grounding of the F-10, airlines eventually turned to the all-metal Boeing 247 (the first modern airliner) and the Douglas DC-2.

2. TWA Flight 6, 1935

A TWA Douglas DC-2, like the one that crashed in 1935 (left). Senator Bronson Cutting in 1928 (right).

On May 6, 1935, TWA Flight 6, travelling from Los Angeles, CA, to Newark, NJ, crashed near Atlanta, MO. On board were thirteen passenger and crew. Five died in the accident, including Senator Bronson Cutting (R-NM).

Shortly before its scheduled arrival in Kansas City, foggy conditions caused the pilot of the DC-2 to divert to Kirksville, MO. However, there seemed to be issues with the radio navigation aid, making it impossible to find the field with instruments alone. Low on fuel, the pilot descended through the fog hoping to catch sight of the landing field. In the dark and fog, the plane’s wing tip struck the ground.

Congress directed a great deal of criticism at the Bureau of Air Commerce. Bronson’s fellow Senator, Royal S. Copeland (D-NY), headed a special sub-committee investigating the Bureau. The committee’s final report blamed the crash on the Bureau’s mismanagement of civil aviation, including providing insufficient funding for navigation aids. The report played a large role in the passage of the Air Commerce Act of 1938 that significantly reorganized aviation regulation in the United States. The legislation created the Civil Aeronautics Authority (the Civil Aeronautics Agency after 1940) and the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB), which had the authority to investigate accidents, establish air safety rules, as well as set the airline fare structure. CAB investigated air crashes until the creation of the independent National Transportation Safety Board in 1967.

3. The Elizabeth, New Jersey, Crashes, 1951-1952

A 1947 advertisement for the Douglas DC-6.

In less than three months, three commercial aircraft crashed in the city of Elizabeth, NJ, a town located near the Newark Airport.

The first accident involved a Miami Airline’s Curtiss C-46 Commando on December 16, 1951. Shortly after take-off, witnesses observed smoke trailing from the airplane’s right side. As the aircraft continued to climb, the situation worsened as witnesses could see black smoke and flames coming from the right engine nacelle and the plane began to lose altitude. While flying over Elizabeth the plane, now at 200 feet, suddenly entered a 90 degree bank. Although the pilot managed to avoid several buildings, the wing tip hit a rooftop and then crashed into a one-story building. All aboard the aircraft died and one person on the ground was seriously injured.

Little over a month later, on January 22, 1952, an American Airlines flight crashed in Elizabeth while on approach to Newark Airport. All 23 people aboard the aircraft died as did seven people on the ground. No cause was ever determined. Then on February 11, 1952, a National Airlines DC-6, crashed less than two minutes after departure from Newark Airport, again in Elizabeth.

Crash investigators blamed a faulty propeller governor in engine 3. It caused the propeller to suddenly go into reverse and the crew mistakenly feathered the number four engine propeller. No longer able to maintain altitude, the plane hit an apartment building and crashed into a nearby field, narrowly missing an orphanage. Twenty-nine of the 63 persons aboard died as well as four people in the apartment building. This third crash led to the temporary closure of Newark Airport.

The National Airlines DC-6, 1952.

Following the crash of a military C-46 while on approach to Idlewild (now JFK), some began to demand the closure of all the New York City area airports. Aviation officials saw the series of crashes as civil aviation’s “Pearl Harbor” event. In response, President Dwight Eisenhower called on aviation icon James “Jimmy” Doolittle to head a commission to investigate safety issues.

The “Doolittle Report” called for a number of measures aimed at making aviation safer in the air and on the ground. The recommendations included the acquisition of more and better aids to navigation, especially those near heavily used airports, the creation of “clear zones” on the approach ends of runways, and new air traffic control rules.

4. Grand Canyon Mid-Air, 1956

A United Air Lines Douglas DC-7 (left). A TWA Lockheed L-1049 Super Constellation (right).

There are basically two sets of “rules” under which pilots fly aircraft–Visual Flight Rules (VFR) and Instrument Flight Rules (IFR). Today, all commercial airliners operate under IFR at all times. Before the mid-1950s, however, commercial airliners could operate under VFR if weather conditions permitted. One of the big differences between VFR and IFR is that under VFR pilots are responsible to “see and avoid” any other aircraft while under IFR air traffic control is responsible for providing information to pilots to help them avoid colliding with other aircraft.

On June 30, 1956, the pilots of United Airlines Flight 718 (DC-7) and TWA Flight 2 (Lockheed Constellation) both decided to shift from IFR flight to VFR flight on a bright and sunny day while flying over the desert of the Southwest. Neither aircraft’s crew were in contact with air traffic control and were essentially flying “off airways.” Over the Grand Canyon, the two aircraft collided, killing 128 people. It was the first airplane accident to result in more than 100 casualties.

The tail section of TWA Flight 2 after its collision with United Flight 718 in 1956.

The tragedy came at a time when Americans were taking to the air in ever greater numbers. And they were flying on larger and faster planes. Congress came under great pressure to once again reorganize the regulation of aviation and modernize the air traffic control system. Additionally, there were immediate calls to place both civilian and military aircraft under a single control system (following mid-air collisions between civilian and military aircraft) and to create a national system of radar control coverage.

Congress responded with the Federal Aviation Act of 1958 that replaced the Civil Aeronautics Authority with the Federal Aviation Agency (the Federal Aviation Administration after 1966) and passed legislation aimed specifically at modernizing the air traffic control system.

5. Trans Australian Airlines Flight 538, 1960

Today, after a commercial aircraft accident, we know that the first thing investigators will do is to carefully examine the aircraft’s “black boxes.” The “boxes” are actually bright orange and contain a flight data recorder and a cockpit voice recorder. The path mandating their use began with Trans Australian Flight 538.

On June 10, 1960, Flight 538, a Fokker F-27, was en route from Brisbane to Mackay, Queensland. Sometime after 10:00 p.m. local time air traffic controllers at Brisbane lost contact with the flight. Earlier in the evening, the pilot had twice aborted approaches into the airport due to low clouds and poor visibility. The plane had been holding off the coast for over an hour at the time of its disappearance.

The interior of a Fokker F-27 in the 1960s.

At 10:00 p.m., the air traffic controller reported improved local conditions to the pilot, who announced he would initiate an approach to the airport. When the air traffic controller sent an update at 10:05 p.m. there was no response. Rescue boats sighted wreckage at 3 a.m. the next day. Two more days would pass before boats found the crash site. It took two weeks to salvage the wreck. Twenty-nine people, including a group of schoolchildren traveling on holiday, perished.

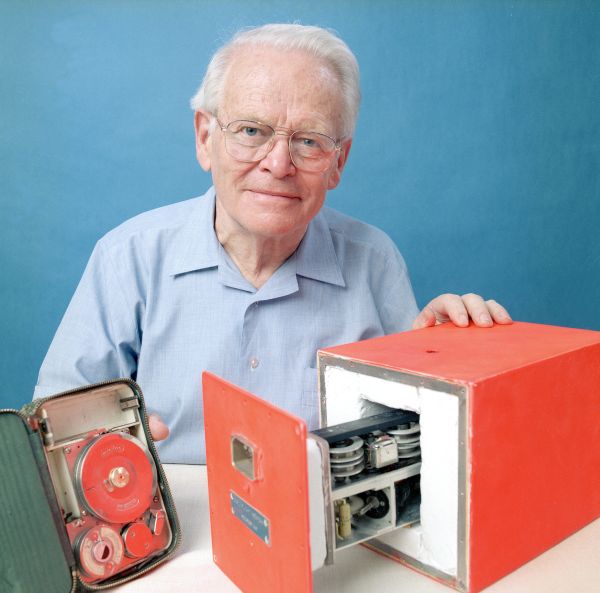

David Warren with his initial prototype of his Flight Data Recorder.

As a result, Australia became the first country to mandate that all commercial aircraft the size of the F-27 or larger carry a cockpit voice recorder, a device invented by Australian David Warren in 1957. Other nations followed the example and by 1967 international regulations required the use of both cockpit voice recorders and flight data recorders. The investigation could not determine a cause. Attention focused on the altimeter, but there was no clear evidence of any malfunction and investigators doubted that the experienced pilot had difficulty reading the instrument. One investigator seized on a small brown bottle found in the cockpit to theorize that one of the schoolchildren aboard had been invited to the cockpit, spilled the bottle, and the pilots had been distracted. Importantly, yet another investigator indicated that it would be very helpful to know what the pilots had been talking about before the crash.

6. Dawson's Field Hijackings (1970)

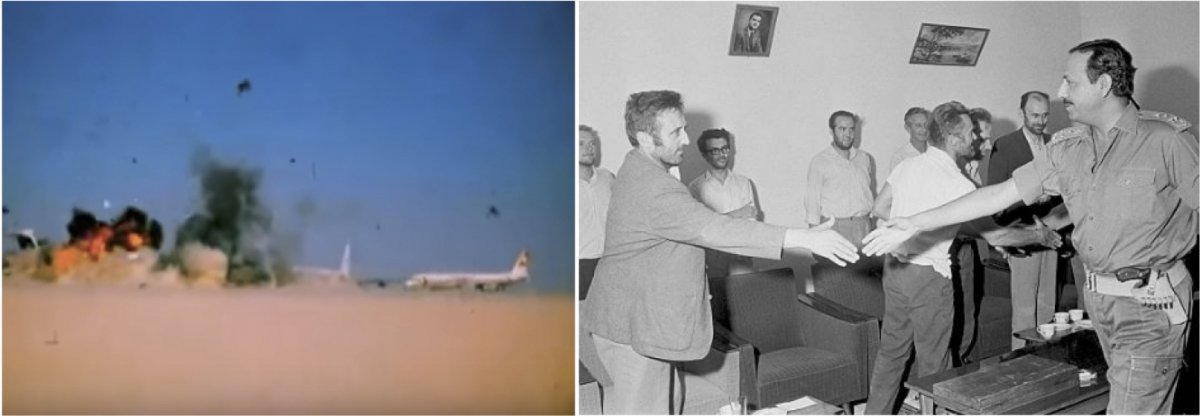

The hijacked planes at Dawson’s Field in Zarqa, Jordan.

Hijackings were not new in 1970. Aircraft hijackings dated back to the 1930s and had become increasingly common beginning in the 1950s despite laws designed to deter them. After numerous hijackings in the 1960s—incidents where, for example, U.S. planes were forced to fly to Cuba—some government officials and individuals involved in commercial aviation called for stricter security measures at U.S. airports.

Oftentimes measures were adopted in the immediate aftermath of an incident, only to be phased out over time as memories of the precipitating incident faded in the public mind. More importantly, most airline and airport officials did not want security measures to interfere with the “flight experience” of travelers. The hijackings in early September 1970, however, were of such a scale as to begin a permanent change in security at U.S. airports.

One of the bombs exploding in front of the international press (left). Jordanian Army chief of staff checking on hostages (right).

Between September 9 and September 13, 1970, members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) successfully hijacked four commercial airliners (a fifth attempt on an Israeli airliner was foiled). Three of the four—a TWA 707, a Swissair DC-8, and a BOAC VC 10—ended up at Dawson’s Field, a former military base in Jordan. The fourth, a Pan Am 747, ended up in Cairo, Egypt. A Pam Am crew member successfully led the rapid evacuation of the passengers upon landing. As the hijackers had threatened, the plane exploded shortly after the last of the crew exited the aircraft. Egyptian police arrested the hijackers.

At Dawson’s Field, the hijackers also planned to destroy the aircraft. As in Egypt, they allowed the evacuation of all passengers and crew before detonating the bombs. Most of the 310 passengers and crew were transferred from Dawson’s Field to Amman, Jordan, but a number of mostly Jewish passengers were held as hostages. On September 12, 1970, the hijackers used explosives to destroy the three planes.

Security measures at Columbia Metropolitan Airport in South Carolina in the early 1970s.

King Hussain of Jordan, who saw the Palestinian actions as threats to his monarchy, declared martial law on September 16. The following day he ordered troops into Palestinian controlled areas of Jordan. Though the action threatened a larger regional war, the quick victory of the Jordanian troops led to an agreement in which the remaining hostages were released in exchange for the members of the PFLP being held by Swiss and British authorities.

The Dawson’s Field hijackings set the stage for the implementation of more strict passenger screening measures that would become familiar to airline customers starting in the early 1970s—the use of the so-called “hijacker profile,” of magnetometers, and of X-ray machines to “search” passenger luggage.

7. Air Canada Flight 797, 1983

Fire damage to the lavatory of Air Canada Flight 797, where the fire is believed to have begun.

Air Canada was en route from Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport to Montreal’s Dorval International Airport on June 2, 1983, when a fire broke out behind the lavatory on the DC-9-32 while the plane was over Louisville, KY. The fire soon spread between the outer skin of the aircraft and the interior panels, filling the aircraft with toxic smoke. The fire also burned through electrical cables servicing the cockpit, disabling most the aircraft’s instrumentation.

The pilot diverted the aircraft to the Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport. The pilot, though struggling to maintain control of the aircraft, made a successful landing and passengers began evacuating through the open doors. However, 90 seconds later, fresh air from those open doors combined with the existing fire to create flashover conditions within the aircraft. The 23 passengers who had not yet evacuated were killed.

The inside of Air Canada Flight 797 after the fire (left). The exterior of the plane (right).

The cause of the fire was never determined. However, as a result the FAA later adopted many fire safety measures suggested by the National Transportation Safety Board. These included the installation of smoke detectors in aircraft lavatories and floor lighting to mark the path to the nearest exit, the use of fire-blocking materials in aircraft seats, better fire detection and fighting training for crewmembers, and the instruction of passengers in the operation of emergency exit doors.

8. Delta Flight 191 (1985)

The wreckage of Delta Flight 191.

Delta Flight 191 was on approach for a scheduled stop at Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport on August 2, 1985. As the pilots began their approach to the airport, they can be heard commenting on rain and poor visibility on the cockpit voice recorder (CVR). A Lear Jet flying three miles ahead of Delta 191 and on approach to the same runway encountered heavy rain, no visibility, and some turbulence. The pilot, however, was able to land the aircraft without incident.

Shortly after the Lear landed, an air traffic controller saw lightning from the storm cell over the approach. The CVR indicated that the pilots of the Delta flight also saw lightning and were soon heard struggling as the plane began to lose altitude. The CVR also recorded the sounds of the engines spooling up as the crew added power. Investigators also heard the pilot order a “go around” or aborted landing just before the ground proximity warning horn sounded.

The aircraft, with its gear down, hit the ground in a plowed field a little over a mile from the end of the runway. The aircraft traveled across the field on its gear until it reached Texas Highway 141 where the plane hit a streetlight and its left engine hit an automobile, killing the driver. The aircraft continued skidding on the highway, hitting two more lights before breaking apart. Most of the aircraft, though, continued its forward momentum, carrying it onto airport property where it collided with two water tanks. By the time the aircraft came to rest, it was fully engulfed in flames. Of the 163 people on the aircraft, 136 passengers and crew died.Shortly after the Lear landed, an air traffic controller saw lightning from the storm cell over the approach. The CVR indicated that the pilots of the Delta flight also saw lightning and were soon heard struggling as the plane began to lose altitude. The CVR also recorded the sounds of the engines spooling up as the crew added power. Investigators also heard the pilot order a “go around” or aborted landing just before the ground proximity warning horn sounded.

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) determined that an intense down draft (wind shear), associated with thunderstorms and rain showers, contributed to the crash. While it also cited pilot error (the decision to attempt the landing through the storm), the NTSB report highlighted the lack of equipment to detect wind shear as well as a lack of training as to how to deal with this weather phenomenon.

Following the crash, researchers at NASA’s Langley Research Center developed an on-board Doppler radar system to allow crew to detect not just thunderstorms, but the drastic wind shifts within them. The FAA mandated the installation of airborne wind shear detection and alert systems on all commercial aircraft. The FAA also mandated that pilots receive training to react to such phenomenon, take evasive action, and land the plane safely.

9. Cerritos Mid-Air, 1986

An AeroMexico Douglas DC-9-30 plane (left). A Piper Pa-28-181 (right).

On August 31, 1986, AeroMexico Flight 498 (DC-9), which had taken off from Mexico City International Airport earlier that day, began its approach into Los Angeles International airport just before noon. At 11:52 a.m., a Piper PA-28-181, a small single engine aircraft on a flight from Torrance to Big Bear City, CA, collided with the DC-9. The larger plane’s horizontal stabilizer sliced through the Piper’s fuselage, killing the pilot and his two passengers.

The Piper then plunged into an empty school playground in Cerritos, CA. The DC-9, which lost its horizontal stabilizer and most of its vertical stabilizer in the collision, nose-dived into a residential community, exploding on impact. The plane’s wreckage scattered across the Cerritos neighborhood destroying four homes and damaging seven. The 64 passengers and crew on the DC-9 died as well as 15 people on the ground.

Investigators determined that the Piper had entered the terminal control area (TCA) for the Los Angeles Airport without the proper clearance. At the time, the air traffic controller was also dealing with an incursion from another private aircraft that had also entered the TCA without clearance. The NTSB placed blame for the crash on the pilot of the Piper.

In the aftermath of this mid-air collision, the FAA required all commercial aircraft to have on-board traffic collision avoidance systems installed by 1989. It also required all aircraft operating within 30 miles of a major airport to have and activate a transponder with Mode C—basically a radio that automatically transmits an aircraft’s position and altitude to air traffic controllers.

10. United Airlines Flight 585 (1991) and USAir Flight 427 (1994)

The United Airlines Boeing 737 plane five years before the 1991 crash.

The recent experience with the 737 Max is not the first time it has required more than one disaster to result in the adoption of safety measures. This was the case with an earlier model of the 737 also involved in two commercial airline crashes.

On March 3, 1991, United Flight 585 was on approach to the airport in Colorado Springs when it experienced a sudden, extreme movement in its rudder. The rapid deflection of the rudder put the aircraft into a right roll in a nose-down attitude. Though the highly experienced flight crew attempted to abort the landing, the aircraft continued to descend and slammed into a park four miles from the end of the runway at 245 miles per hour.

All 25 passengers and crew died in the fiery crash. Despite an extensive and lengthy investigation, the NTSB could not find a definitive cause for the crash. It was only the fourth time in history that a report was issued without a firm conclusion as to cause.

The cause remained a mystery until a similar crash on September 8, 1994, in Pittsburgh, PA. USAir Flight 427, en route from Chicago, was on final approach to the Greater Pittsburgh International Airport. It was flying behind a Delta 727. As USAir 427 experienced the wake turbulence of the Delta aircraft, it also experienced a sudden roll to the left in a nose down attitude and stalled.

A photo taken of the impact crater from USAir Flight 427 taken during the investigation (left). Wreckage recovered from the site for analysis (right).

The pilots fought for control, but the aircraft continued to roll left and descend, subjecting the passengers and crew to a 4g load. While in an 80-degree nose-down position, banked 60 degrees left, and while traveling at approximately 300 miles per hour, the plane crashed and burst into flames. It had been 28 seconds since the aircraft first experienced the wake turbulence. All 132 on board died.

The crash of USAir 427 resulted in the longest investigation in NTSB history.

The final report was released four and a half years after the crash. Investigators determined that the accident had been caused by mechanical failure—a faulty servo valve in the plane’s rudder control system. The NTSB also concluded that the mechanical failure had been the cause of the United Airline disaster in 1991 and well as an incident with Eastwind’s Flight 517 in June 1996, though in that case the pilots had been able to successfully regain control of the aircraft.

Though Boeing rejected the findings, it did agree to redesign the rudder control system, including a redundant back-up, and paid for the retrofitting of all existing 737s worldwide. Since the rudder redesign, there have been no similar accidents or incidents. The FAA also required that flight data recorders receive and capture additional information on pilot rudder commands, a change made by August 2001.