Russians have featured prominently in the American press recently. Whether regarding Ukraine, Syria, or allegations of hacking in the 2016 American presidential election, those “mischievous Russkies” seem to be everywhere. Even though the U.S. and Russia have never engaged in a hot war with one another, American pundits and politicians almost always cast Moscow as the perpetual “enemy” of American national interests—a view informed by antagonism between the U.S. and the USSR in the Cold War.

However, have the U.S. and Russia always been “enemies” as American political and media elites contend? History tells us otherwise. Although the bad episodes are clearly what most Americans remember about the relationship, there were many friendly moments as well. These constructive episodes complicate a history that is often painted as invariably antagonistic. Keeping this complexity in mind, here are ten of the better moments in U.S.-Russian relations.

1. Russia and the American Revolution

Russian Empress Catherine the Great by Fyodor Roktov, 1770.

The original Thirteen Colonies began to engage in trade with Russia in 1763, in violation of the Navigation Acts. During the Revolutionary War, Russian Empress Catherine the Great decided to remain neutral in the conflict, despite British pleas for assistance. The Empress was sympathetic to the colonists and believed that an independent America would be beneficial to Russian commercial interests in North America. Russian neutrality proved significant for the victory of the American rebels. After the Revolution, the liberal-minded Tsar Alexander I famously corresponded with Thomas Jefferson and expressed his “great esteem” for the American project, which he viewed as a potential model for reform in Russia. In addition to the Tsar, several participants of the 1825 Decembrist Revolt were also influenced by the American Republic.

2. Russia and the American Civil War

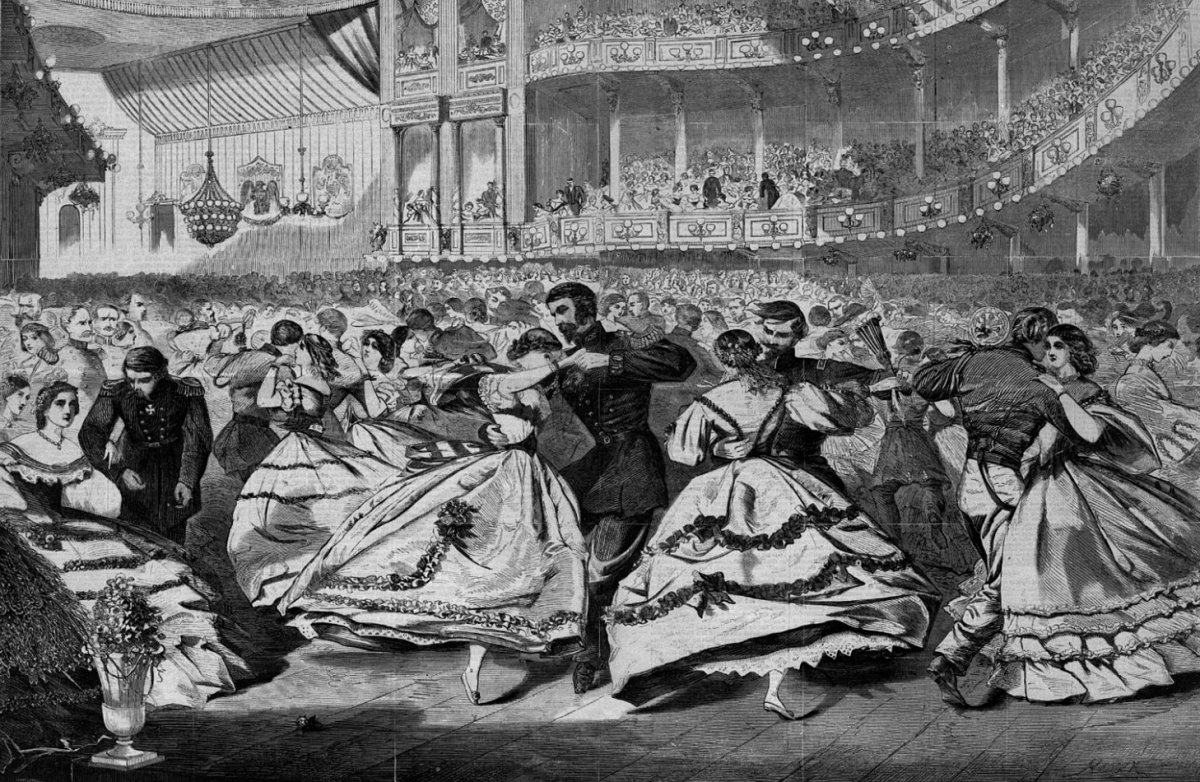

The Great Russian Ball at the Academy of Music, New York by Winslow Homer, 1863.

As the American Civil War unfolded, Tsar Alexander II pledged in a letter to President Abraham Lincoln that Russia supported the “maintenance of the American Union as one ‘indivisible nation.’” In 1863, the Tsarist state dispatched part of its fleet to the ports of New York and San Francisco with visits to Boston and Washington. Grand parades and elaborate balls were held in their honor. Indeed, the Union interpreted the Russian presence as a sign that Petersburg would intervene on their behalf if Britain and France chose to side with the Confederacy. However, the motivation for Russia’s action was not limited to a desire to support the Union alone. Fearing a possible British or French attack, Petersburg also sought to remove its ships from home waters and station them in Union ports.

3. The Friendship of Lincoln and Alexander

Alexander II by Ivan Tyurin (left), and Abraham Lincoln by George P. A. Healy, 1860s (right).

Both the American President Abraham Lincoln and Russian Tsar Alexander II played the role of emancipator. On March 3, 1861, roughly six weeks before the American Civil War began, Tsar Alexander II of Russia issued his Emancipation Proclamation, freeing 20 million Russian serfs. On January 1, 1863, Lincoln issued his own Emancipation Proclamation declaring all enslaved Americans to be free. Both proclamations changed the course of the histories of their respective countries, even if their effects were not immediately felt. Both men corresponded with one another and Alexander even referred to Lincoln in his letters as “your very affectionate friend.” “I – and with me all Russia – appreciate the testimonials of friendship which they [Congress] have given me,” wrote the Tsar to the President. “How heartily I shall congratulate myself on seeing the American nation growing in power and prosperity by the union and continued practice of the civic virtues which distinguish it.” Unfortunately, both men also met a similar fate: assassination.

4. The Sale of Alaska

Russia maintained a presence in North America for many years. Centered in present-day Sitka (then Novoarkhangelsk), Russian America eventually encompassed all of Alaska and parts of California and Hawaii. However, Alaska proved to be a costly possession for Petersburg to maintain and supply. A sale of the far-flung territory to the United States seemed to be the best option for the Tsarist state, given its warm relations with Washington. In the end, Alaska was sold to the U.S. for $7.2 million (total $123 million today) in 1867 in a treaty with Russia negotiated and signed by U.S. Secretary of State William Seward. At the time, the sale was domestically greeted with ridicule in the U.S. and was popularly derided as “Seward’s Folly.” How could America possibly benefit from a frozen Arctic wasteland?, Seward’s critics inquired. However, the criticism subsided after the Klondike Gold Strike in 1896, vindicating Seward.

5. FDR Restores Relations with USSR

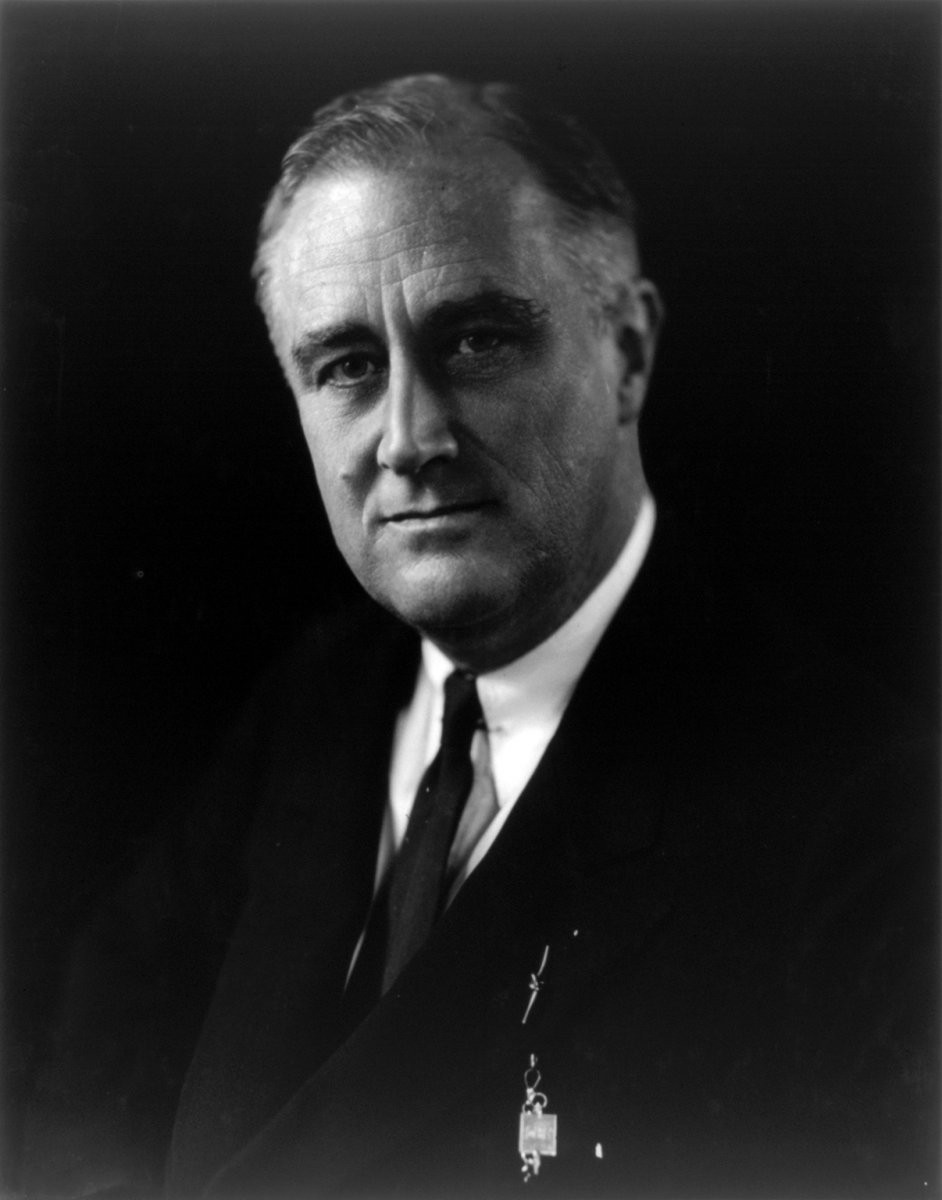

American President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 1933.

After the Russian Revolution and the victory of the Bolsheviks in the Russian Civil War, panic gripped the United States as the first Red Scare swept the country. Throughout the 1920s, Washington refused to recognize the newly established Soviet government. After his election to the presidency in 1932, Franklin Delano Roosevelt sought to challenge this orthodoxy. Though the State Department was dominated by individuals opposed to dialogue with Moscow, FDR succeeded and recognized the USSR in November 1933. In an interview with Origins, Ambassador William vanden Heuvel said that “FDR saw the Soviet Union as a possible counterweight to the emerging threat of Hitler and the Nazi movement in Germany. Having diplomatic relations with the USSR was a crucial dialogue. Both the U.S. and the Soviet Union saw the possibility of significant trade, which in the depth of the Great Depression, provided much hope.”

6. U.S.-Soviet Cooperation in World War II

On June 22, 1941, Nazi Germany launched an all-out assault on the Soviet Union’s western frontier, thus beginning Operation Barbarossa. Only a few months later, on December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor was attacked by the Japanese, signaling the entrance of the United States into World War II. Washington and Moscow were now allies in a major global conflict and cooperated extensively during the war. Most notably, the American Lend-Lease program was crucial to Soviet victory over the Germans. The Soviet contribution to the war effort was widely covered by the American press and became the subject of popular wartime songs and ballads. Perhaps the most important day of the war for the alliance was the historic meeting of Soviet and American soldiers on the Elbe River in Germany on April 25, 1945. The moment signaled a high point in American-Soviet relations immediately prior to the onset of the Cold War.

7. The U.S. and USSR Agree to Avoid Arms Race in Outer Space

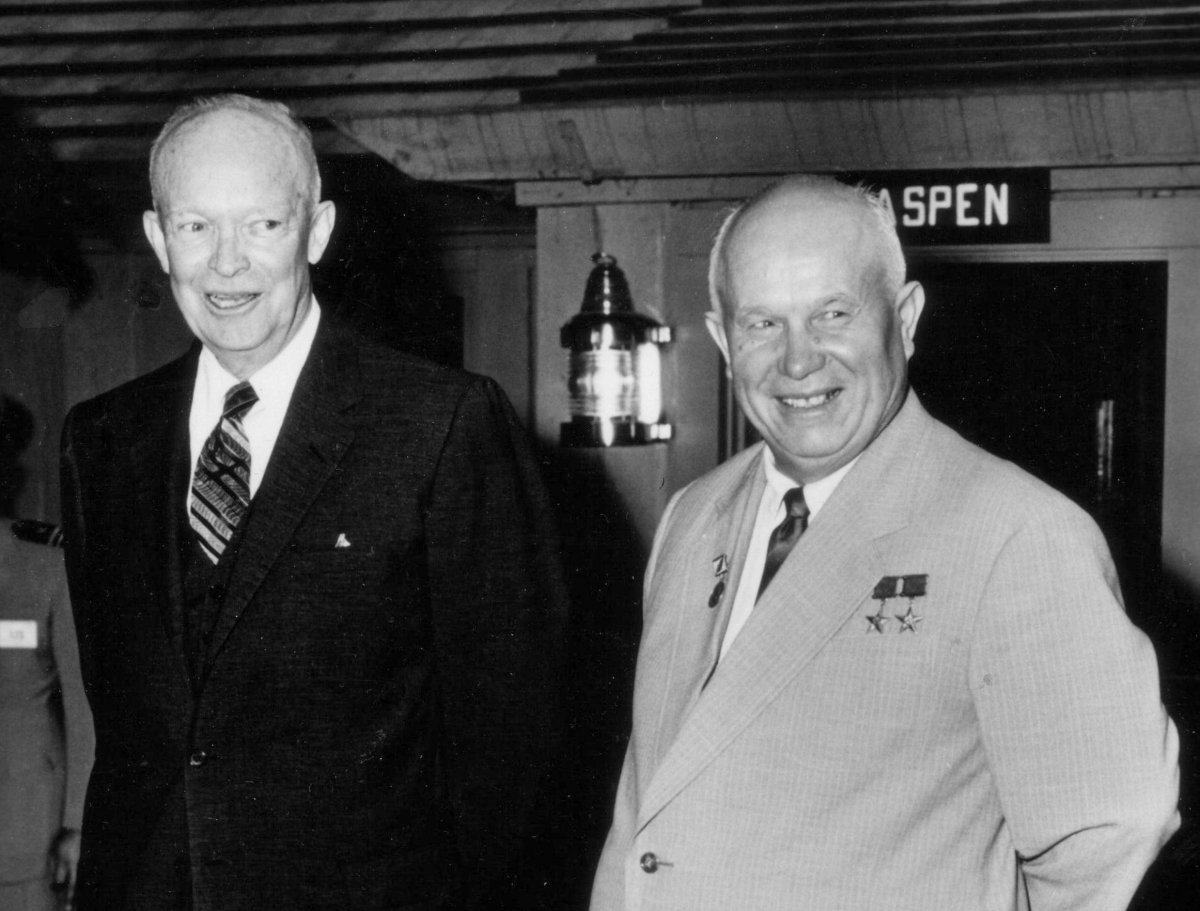

American President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev at Camp David, 1959.

In the darkest days of the Cold War, American President Dwight D. Eisenhower sought to stop a further escalation of conflict by preventing the expansion of the Soviet-American arms race into outer space. Instead of concentrating U.S. aeronautical development within the Air Force or Army, Eisenhower established a civilian space agency, NASA, in 1958. He also sent letters to Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev proposing the use of space for exclusively peaceful purposes. However, Khrushchev made Eisenhower’s plan conditional on the removal of nearby nuclear missile installations in Turkey. Thus began a process that finally culminated in the acceptance by both sides to keep outer space free from the arms race. The Kennedy administration appealed to Moscow for potential cooperation in space and, by this time, Khrushchev was ready to work with Washington. In 1967, the U.S. and the USSR signed the Outer Space Treaty, prohibiting the militarization of outer space.

8. Nixon’s Détente with the USSR

Soviet General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev and American President Richard Nixon, 1973.

Upon coming to office in 1969, U.S. President Richard Nixon sought a thaw in American-Soviet relations, known as détente. “I told [Nixon] the Soviet Union favored peaceful cooperation and if the United States would proceed from the same principle, broad possibilities would open for the solution of pressing international issues,” wrote former Soviet Ambassador to the U.S. Anatoly Dobrynin in his memoir In Confidence. “Nixon said that in principle he agreed with these goals and attached major importance to the improvement of relations with the Soviet Union.” Nixon held several high-level summits with Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev. The new policy of détente proved fruitful and led to three major agreements with the USSR: SALT I (Strategic Arms Limitation Talks), the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, and the Biological Weapons Convention in 1972, and the Helsinki Accords in 1975. These agreements served as a solid foundation for good relations between the two superpowers.

9. Samantha Smith’s Letter to Soviet General Secretary Yuri Andropov

Samantha Smith (center) at the all-Union Artek pioneer camp during her visit to the USSR, 1983.

In 1982, relations between the U.S. and the USSR were in a state of deep freeze. The prospect of nuclear war loomed large. However, this did not stop Samantha Smith, a ten-year-old girl from the U.S. state of Maine, from writing a letter to the leader of the “evil empire,” Yuri Andropov. “I have been worrying about Russia and the United States getting into a nuclear war,” she wrote. “I would like to know why you want to conquer the world or at least our country. God made the world for us to live together in peace and not to fight.” Ultimately, Andropov responded thanking Smith for her letter and invited her and her family to visit to USSR, where they spent two weeks in 1983. Unfortunately, Smith died in a tragic plane crash in 1985, but her letter set the stage for enhanced people-to-people contacts between the two societies.

10. Reagan and Gorbachev at Reykjavík

U.S. President Ronald Reagan, who was known for his tough stance on the Soviet Union, first met reform-minded Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in Geneva in 1985. Their next meeting would prove to be their most consequential. The two men met for talks at the Icelandic capital Reykjavík in October 1986. Jack Matlock, Reagan’s ambassador to the USSR, noted in an interview with Origins, that the Reykjavík Summit “seemed to many to be a failure at the time because there was no agreement on another meeting.” “However,” he added, “it was probably the turning point in Reagan’s relationship with Gorbachev. They agreed on much more than was acknowledged at the time.” The summit eventually resulted in the sweeping Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) of 1987 and in the end of the Cold War between the superpowers.

BONUS: Billy Joel’s Concert Tour of the Soviet Union

Mikhail Gorbachev’s policy of glasnost’ (openness) created new opportunities for encounters between the U.S. and the USSR. In 1987, the Soviet Union received a high-level visitor: American rock musician Billy Joel. Soviet society was no stranger to Western rock music and boasted its own prominent rock groups like Kino. However, Joel was the first major American rock musician to perform in the USSR, playing six concerts: three in Moscow, three in Leningrad (St. Petersburg). Accompanied by then-wife Christie Brinkley and his daughter Alexa, the piano man visited Soviet Georgia and the grave of Soviet bard Vladimir Vysotsky. Most consequential was his new friendship with Viktor, a Russian clown who became the inspiration for Joel’s hit song Leningrad. As U.S.-Russian relations enter what some fear to be a “new Cold War,” Joel decided to produce a film about his concert in 2014, highlighting the possibility of peace between both countries.