The beginning of China’s Cultural Revolution in 1966 heralded a decade-long period of political turmoil that included attacks on alleged class enemies, the toppling of Party officials high and low, and the reinstatement of political control via revolutionary committees supported by the military. The Cultural Revolution was simultaneously a political and a cultural movement, aiming not only at political upheaval but also the transformation of social and cultural life through Mao Zedong Thought.

An exhibition of Mao badges at the Jianchuan Museum Cluster in Anren, Sichuan Province, a private collection of Mao-era artifacts. Photo by the author.

Historians refer to China’s Mao years as the period from the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 until his death in 1976. The Cultural Revolution decade that concluded the Mao years has been called “Mao’s Last Revolution,” the peak of high socialism. In 1981, the Chinese Communist Party offered its verdict of this era, but both popular memory and recent scholarship challenge the official interpretation.

The Cultural Revolution as Anniversary

What was the official beginning of the Cultural Revolution?

The scholars Roderick MacFarquhar and Michael Schoenhals call Mao’s attacks on the historian Wu Han in early 1966 the Cultural Revolution’s “first salvos.” This year journalists and others—including the Chinese Communist Party’s official newspaper, the People’s Daily—chose May 16 as the date when Mao Zedong articulated the justification for Cultural Revolution.

This article uses August 8 as the date when the central leadership adopted a decision on the Cultural Revolution, one that was published in the newspaper the following day.

|

| On the campus of Beijing’s Tsinghua University, a statue of the historian Wu Han was erected in 1986. During this relatively open period, the inscription on the back of the statue included his suffering during the Cultural Revolution. Photo by Yifu Dong. |

The convention for marking the end of the Cultural Revolution is less ambiguous; most link it to Mao’s death in September of 1976, or to the subsequent arrest and trial of the Gang of Four, a group of political allies that included Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing.

By the Communist Party’s own official verdict in 1981, known as the “Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party,” the Cultural Revolution lasted from May 1966 to October 1976. The resolution acknowledged the period’s tragedies and called them mistakes, laying blame at the feet of the Gang of Four and others, including Mao himself.

However, it was also a document of affirmation, one that—in condemning the Cultural Revolution’s excesses as leftist mistakes—underscored the priorities of socialism, the leadership of the Party, and Mao’s revolutionary legacy. Thirty-five years later this official pronouncement remains the accepted interpretation. Writing on the fiftieth anniversary this May, the People’s Daily reiterated that the resolution “gave correct conclusions on a succession of major historical issues,” and that these conclusions “possess unshakable scientific truth and authority.”

But the very need to state that the official historical interpretation is true belies a uniform and authoritative understanding. The Cultural Revolution, on the contrary, remains a period for historical debate. Just as we might debate what date marked its beginnings, we might also debate what the Cultural Revolution was. New accounts, both popular and scholarly, reveal multiple understandings of the Cultural Revolution: what it was, what it was to whom, and why it mattered.

The Cultural Revolution as High Politics

In its beginnings, the Cultural Revolution was viewed from the lens of high politics. The journalists who observed as it unfolded made note of hierarchies of power, and the political scientists who wrote its first histories used the sources then accessible, official news reports and speeches that were shaped and given by those in political control.

The Cultural Revolution as high politics is the story of Mao and his inner circle, of the Central Cultural Revolution Group, of loyalty and betrayal. The milestones of this narrative include the attack on and fall of Liu Shaoqi, the Chinese head of state, and later the alleged planned coup and mysterious death of Lin Biao, Mao’s right hand man.

The 1981 resolution is in large part a story of high politics; it exonerates Liu and excoriates Lin Biao and the Gang of Four. Though the resolution makes brief mention of the “masses” and the “people” as workers, peasants, soldiers, intellectuals, youth, and officials, they are a faceless and nameless backdrop to the drama of central power.

And yet we know that the Cultural Revolution as a political movement was far more than high politics. As ordinary people experienced it, the Cultural Revolution was decidedly local, whether it became factional fighting within one’s school or work unit, or attacks on local powerholders and the creation of new revolutionary committees, or punishment and violence meted on class enemies old and new.

In a recent book, historians Jeremy Brown and Matthew Johnson highlight the difficulty of trying to separate out state officials from others in society. They call instead for a focus on everyday life at the grassroots because this was a time when state and society at the local level shared the same face. To look beyond high politics is also to acknowledge that there were many Cultural Revolutions.

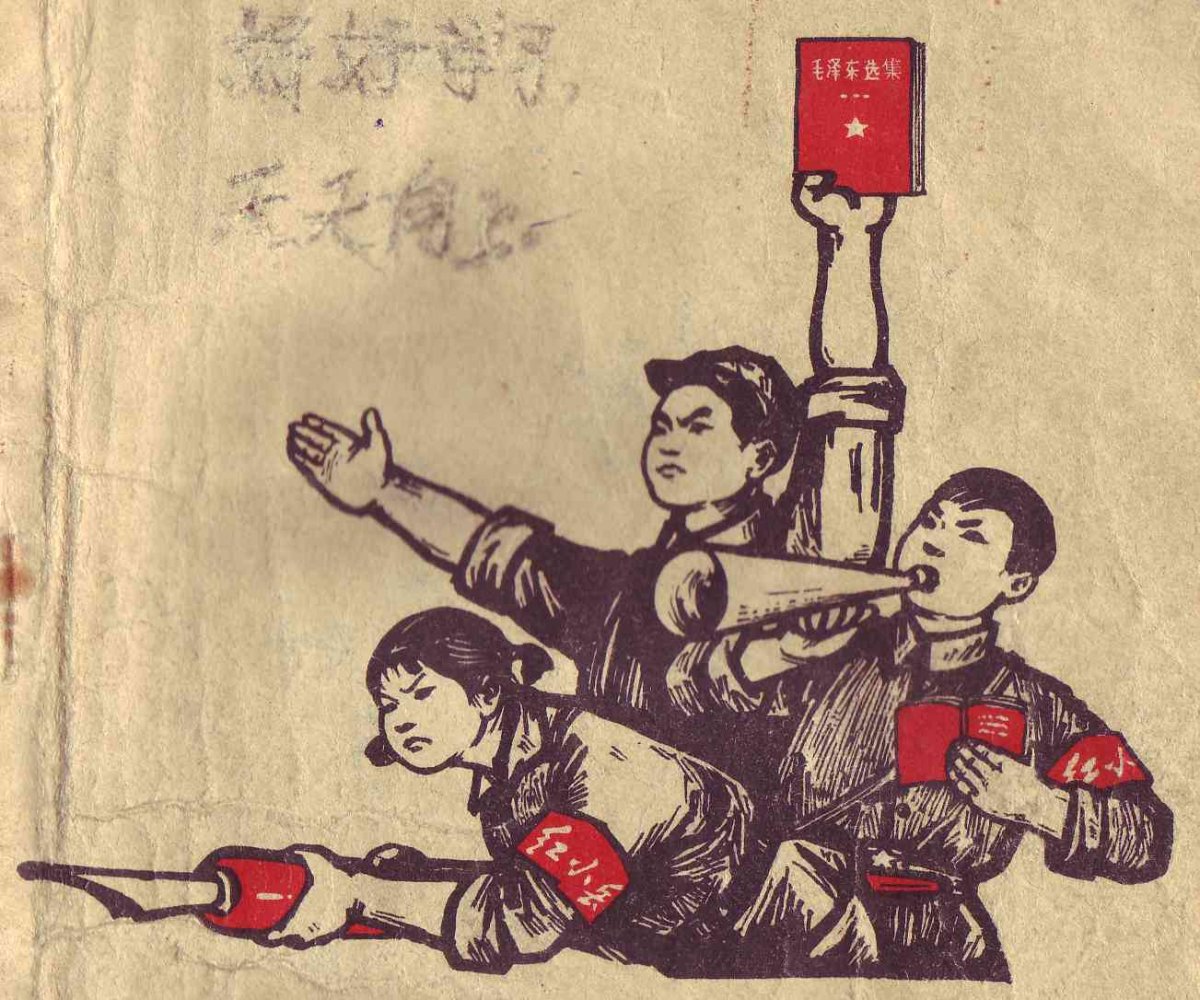

The Cultural Revolution as Red Guards

Use the word “Cultural Revolution” and people think immediately of the iconic Red Guards. There is good reason for this: Mao himself celebrated youth, young people were truly inspired to make revolution, the Red Guards were—through their actions and their portrayal—made a symbol of the Cultural Revolution.

They flooded the streets in military uniforms to destroy the “old world,” they gathered by the million in rallies on Tian’anmen Square, and they went on epic journeys to reenact the Red Army’s historic Long March and to “exchange revolutionary experience.” Red Guards were both the sources of terror and the subjects of propaganda, Chairman Mao’s “revolutionary successors.” They were demobilized and sent to the country by 1968, becoming the generation of the “sent-down youth” and coming of age in exile.

For young people the Cultural Revolution had its own chronology: the heady days of 1966, their rustification (moving from urban areas to the countryside) in 1968, and then long years of waiting before opportunities to go home were even possible.

But if Red Guards were the most visible—and today most remembered—group of participants, they were by no means the only one. Many young people did not participate in the Red Guard movement, and for them these years were marked by political apathy or other kinds of intellectual searching. Unmoored by the strictures of school and adult authority, they wandered and read forbidden books.

And of course, our focus on young people who would have been at school is to privilege a certain group. In Shanghai, for example, the Cultural Revolution’s participants included the industrial city’s workers, many of whom were discontent with stagnant economic conditions and systemic and rigid class structures. Other cities were engulfed with such factional violence to such an extent that order was restored only through military takeover.

However, it is the Red Guards who come to mind first, for a number of reasons—they were and are an icon that inspired others in the Global 1960s, and the youth of this generation became today’s leadership. In the Red Guards rest two central tropes of the Cultural Revolution: the utopianism of youth and the danger of chaos. The hot blood of youth is easier to forgive than the machine of the state, and chaos is easier to blame than power.

The Cultural Revolution as Urban and Intellectual

Scholars of the Mao period often make the point that we know much more of the Cultural Revolution, with its estimated over one million deaths, than we know of the Great Leap Forward movement and its subsequent rural famine (1958-1961), which claimed an estimated thirty million deaths. This is partly because many of those who suffered in the Cultural Revolution were intellectuals, but this is also because intellectuals are people who write, and after the Cultural Revolution these victims’ memoirs, literature, and essays were ways in which people could make sense of its suffering.

When people refer to a Cultural Revolution’s “lost generation,” they usually mean the young people who were sent to the countryside and who received limited schooling. But another way to think of a “lost generation” is to think of the elder generations who were silenced by previous political campaigns, who spent the decade imprisoned in so-called “ox pens” and assigned to menial labor, and who lost the opportunity to build “New China,” a chance some even returned from abroad to pursue. And of course many did not live to see the Cultural Revolution’s conclusion nor their names rehabilitated.

Without denying the tragedy of urban intellectuals, new scholarship has turned to the countryside to uncover different narratives. Some scholars, comparing the Mao years to the post-Mao years of reform, argue that some Cultural Revolution policies had a leveling effect that brought positive benefits to the countryside, including educational opportunities at all levels. Others have found the emergence of economic strategies that went against the planned economy, suggesting that reform-era policies built on a previous record of success.

But the countryside also had its tragedies. The sociologist Yang Su, for example, has shown how episodes of collective killings unfolded in the countryside in Guangdong and Guangxi Provinces, the distance from a center of power creating the conditions for violence against supposed class enemies. Systemic and targeted violence continued to unfold in later Cultural Revolution campaigns; unlike the Red Guard movement, this violence took place away from the public eye. We are only starting to explore the Cultural Revolution experience of those doubly marginalized: in rural areas and of ethnic minority status.

The Cultural Revolution as Social Transformation

The Cultural Revolution was the culmination of Mao’s efforts to transform Chinese society. This was manifest not only in slogans to “bombard the headquarters” and “overturn heaven-and-earth,” but also in the movement’s very premise. If others in the Communist Party leadership had believed that transforming society’s economic structure would ultimately lead to cultural transformation, Mao suggested otherwise: cultural transformation would herald the victory of China’s revolution.

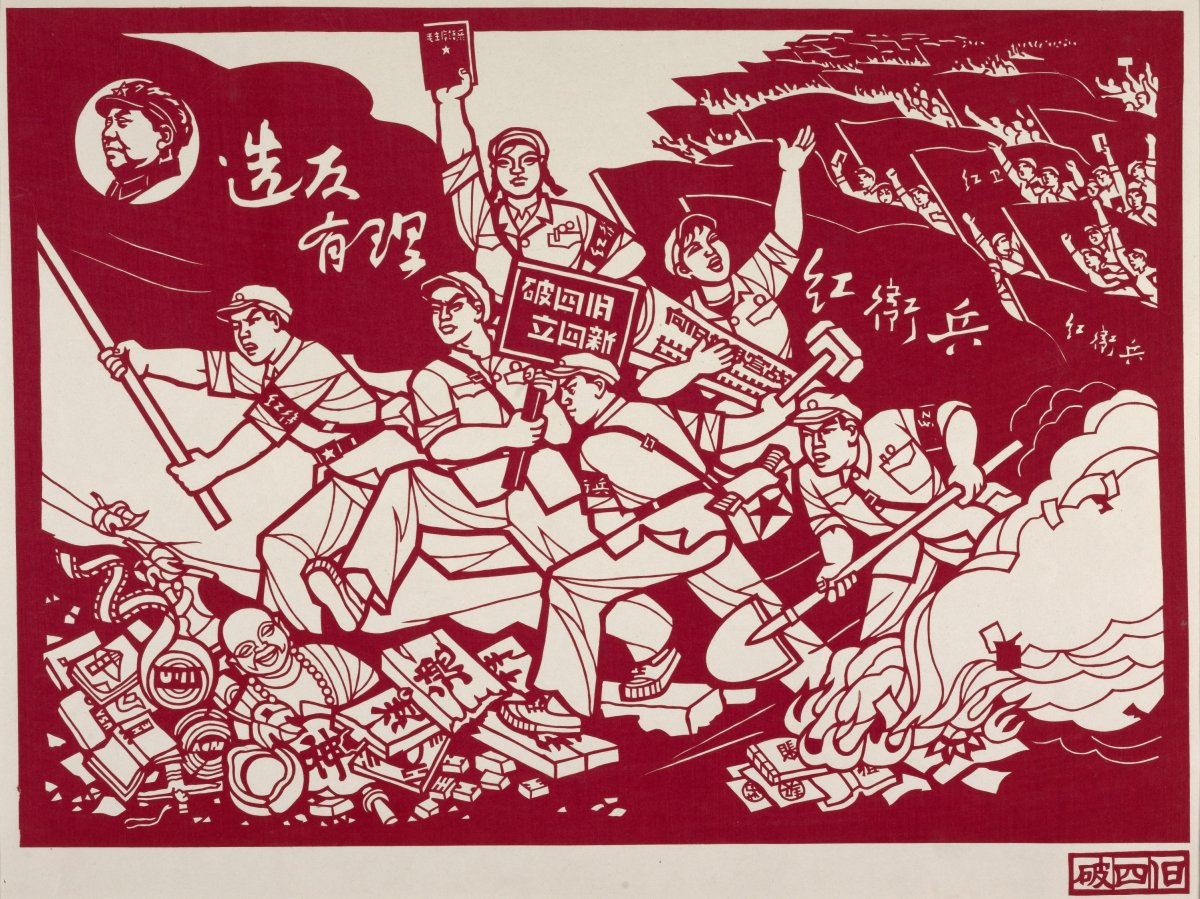

"Eliminate the Four Olds and Establish the Four News," 1967 propaganda poster.

To be sure, the Cultural Revolution—and the Mao years at large—did change Chinese society: it overturned traditional family relationships, it called knowledge into question (substituting “red” for “expert”), it discredited authority political and intellectual, and it defined class not just in terms of property but also through history, standpoint, and behavior. Some critics of the Cultural Revolution today regard it as period in which traditional Chinese society was destroyed, with deep repercussions in our present.

Yet there is another way of framing the narrative of social transformation, one that takes Cultural Revolution rhetoric at face value. That is, that the Cultural Revolution was truly—in its origins—an attempt to prevent revisionism from taking hold in China’s Communist Revolution, that it was an attack on the class privilege that arose from socialist China’s bureaucratic system, and that it was an argument that class behavior should matter more than class background.

Studying bottom-up responses, what he calls “the Cultural Revolution at the margins,” anthropologist Yiching Wu makes the case that some individuals did take all of Mao’s claims seriously, but in their—sometimes brutal—silencing, the state foreclosed discussion of both these critiques and their alternate utopian visions. This version of the Cultural Revolution story is a foundation narrative for today’s authoritarianism.

The Cultural Revolution as History

Can the Cultural Revolution be history?

For the Chinese Communist Party, the Cultural Revolution is history in the sense that it is past. There was a verdict in 1981, and an historical accounting that rendered Mao Zedong seventy percent good and thirty percent bad. If the 1981 resolution concluded by discussing economic gains—among others—achieved during the ten years of turmoil, today’s Chinese regime under Xi Jinping claims that the same document has “withstood the test of experience, the test of the people, and the test of history.”

What the People’s Daily means by “the test of the people” is unclear, but by “the test of history” the editorialist argues that the post-Mao era of reform was successful because it negated the Cultural Revolution. He also criticizes “meddling from the left and the right that focuses on the problems of the Cultural Revolution,” suggesting that somehow any investigation that does not accord with official interpretation might lead China on a backward slide to 1966.

On the side of the former home of the landlord Liu Wencai in Anren, Sichuan Province, remnants of a Mao Zedong quotation linger from the Cultural Revolution. Photo by the author.

But if “being history” is to be examined, researched, analyzed, critiqued, and debated, then the official history of the Cultural Revolution is not history. In China today, many individuals—from amateur historians who seek their family history to academics who must publish in limited ways or abroad—are doing history, even if they cannot do so openly.

Some of these scholars are doing the work of preservation, hoping that future generations may be able to write a people’s history of the Cultural Revolution. Outside of China more can be published, but these scholars also work with limited sources and restricted access. The Cultural Revolution will become history when all of these historians can submit to “the test of history,” to see if the images we make are indeed an accurate mirror.

The Cultural Revolution will be history when it belongs to the public, when it allows for grassroots accounts, access to sources, social reckoning, and the right to memorialize. In China today there is but one officially designed Cultural Revolution historic site, a graveyard in the city of Chongqing where Red Guards who died in factional fighting are buried—but it is locked, off-limits to all but descendants.

On university campuses, one can see busts and statues of individuals whose dates reveal that they died in the ten years of turmoil—but such monuments are celebrations of lives rather than investigations into their endings. There are few other traces, save glimpses of faded slogans on old buildings—but these markings are an idle curiosity, often slated for demolition (see photo above). Only when ordinary citizens can choose how to mourn, what to remember, and which traces to preserve can historical event face “the test of the people.”