Fifty years ago, in December 1969, the Provisional IRA was born from the widespread religious violence that had wracked the six counties of Northern Ireland since the preceding August. From modest beginnings, the Provisionals became the most important and dangerous separatist paramilitary group during the thirty-year conflict in Northern Ireland known as the Troubles. By the time the violence ended in the late 1990s, the Provisional IRA had killed more than 1800 people, roughly half of the victims of the entire conflict.

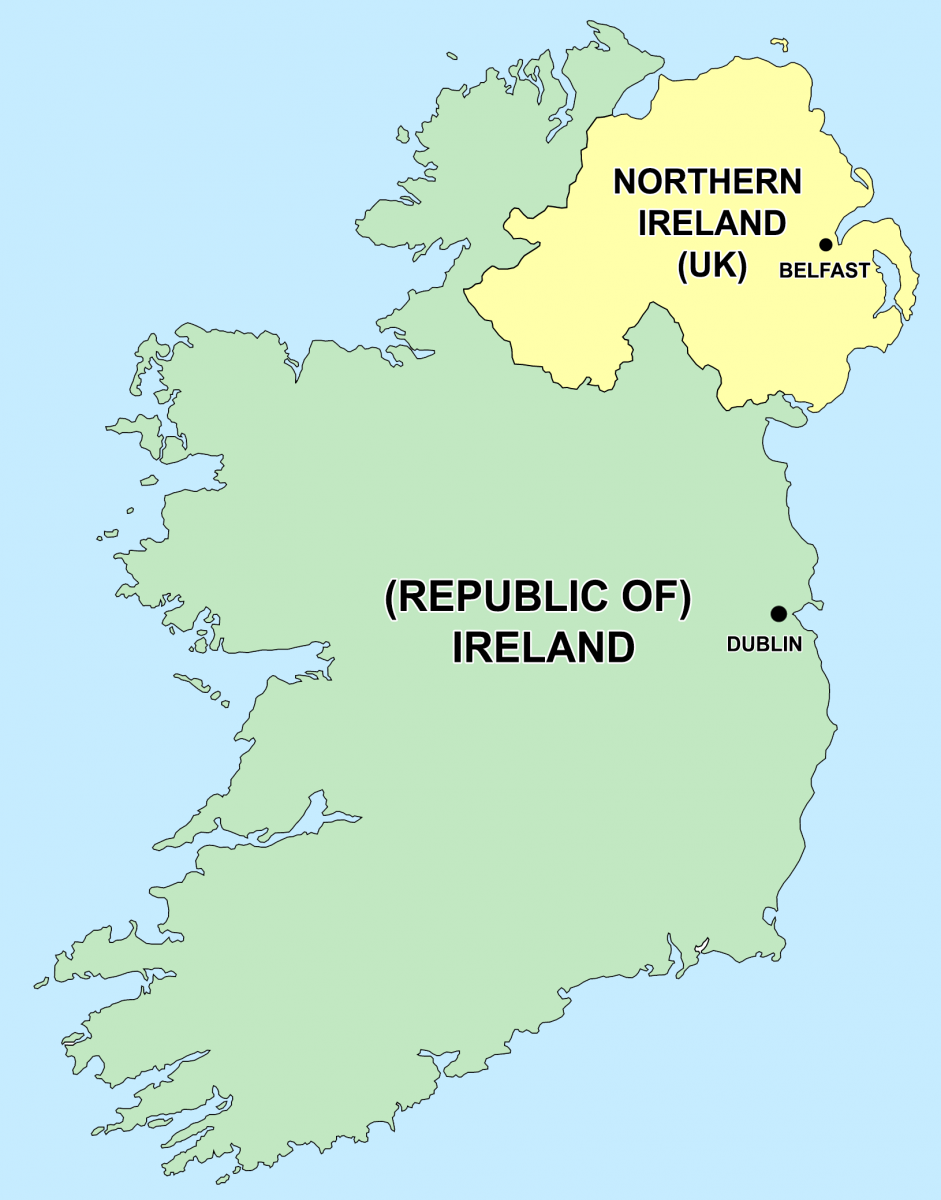

The six counties of Northern Ireland were and remain legally part of the United Kingdom, separated from the Republic of Ireland in 1922 in the aftermath of Ireland’s struggle for independence.

Two thirds of the population of Northern Ireland were Protestants, most of whom felt a strong sense of allegiance toward the United Kingdom. Known as Unionists, they monopolized political and economic power. The remaining third of the population, known as Nationalists, were Catholic and usually identified themselves as Irish rather than British. Most were bitterly resentful of their second-class status.

To rectify this inequality, in 1967 the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) was formed, inspired by the American Civil Rights movement. NICRA sought to end the widespread discrimination against Catholics in Northern Ireland by demonstrating peacefully for the full and equal civil rights that Catholics were due as citizens of the United Kingdom.

Unionists feared that Catholic equality might be the first step toward reunification with the overwhelmingly Catholic Republic of Ireland, an utterly unacceptable outcome. They therefore fiercely fought the civil rights movement—and all efforts to reform the six counties.

Peaceful Catholic marches were met with stones, police batons, and water cannons. By August 1969, demonstrations turned into widespread rioting, arson, and ethnic cleansing that left nearly a dozen Catholics dead and hundreds homeless in Belfast. The police, overwhelmingly Unionist, were complicit in the violence, leaving Catholics with no obvious defenders.

A civil rights march in Northern Ireland, 1968.

In years past, the role of defending Catholics in Ireland had been played by the Irish Republican Army (IRA). Formed in the early 1920s, the IRA originally served as the military muscle of Ireland’s independence movement. Afterward, members of the IRA rejected the conditions of the peace treaty, which included the division of Ireland. However, their political and military influence in both the north and the south declined in the following decades.

In Northern Ireland, the IRA had dwindled to a small number of poorly armed members, too few to respond to the violence of 1969. Humiliated into action, IRA members held a general army convention in December to coordinate their response to the crisis. It was clear that a resurgent IRA would play a central role, but the delegates were divided on the nature of this resurgent IRA.

Most delegates at the convention believed that the time had come for the IRA to drop its long-standing policy of abstention and to enter politics.

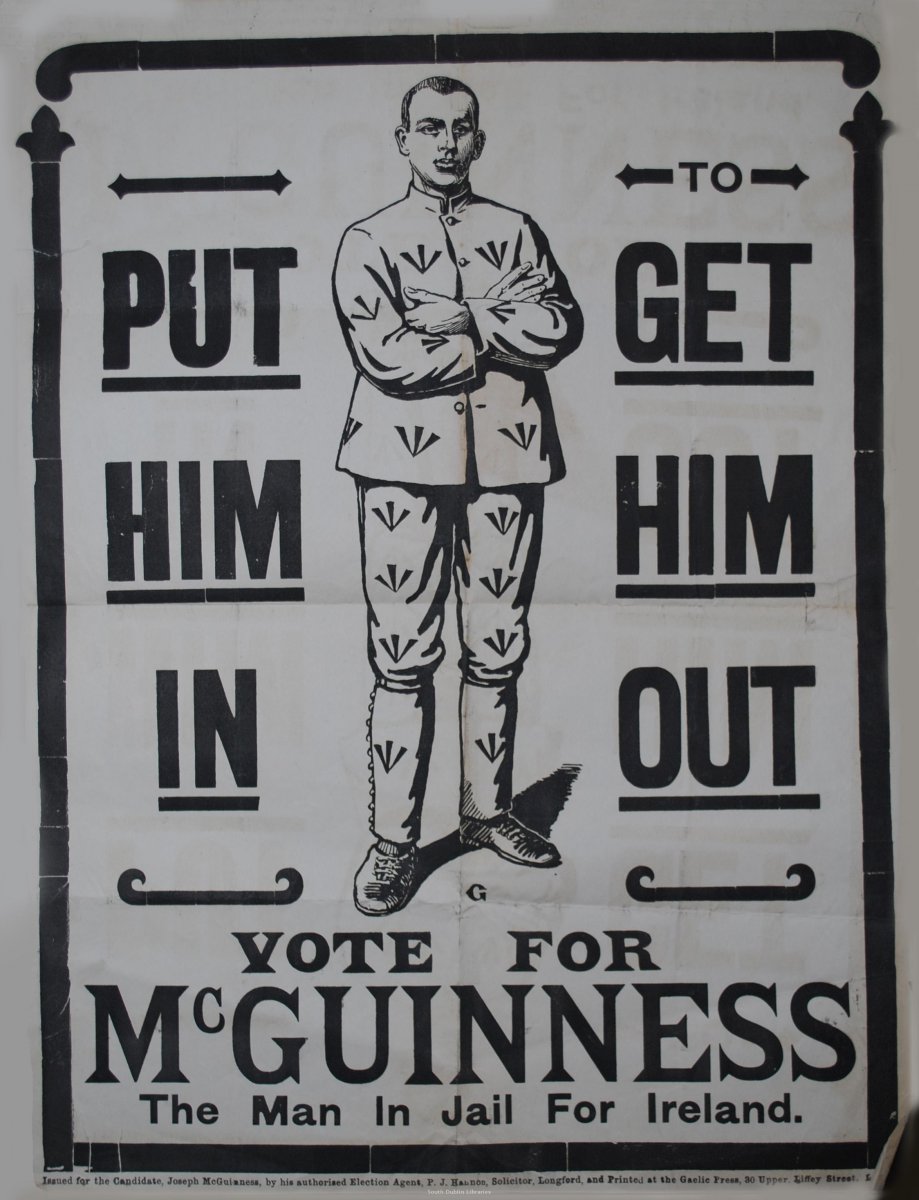

Abstention meant that political candidates affiliated with the IRA and its political counterpart, the Irish nationalist party Sinn Fein, pledged to abstain (that is, never to take a seat, even if elected) in either of the electoral bodies that represented the two halves of the island: the British Parliament or the Irish Oireachtas.

Abstention stemmed from the principle that the division of Ireland was wholly illegitimate and that no true Irish parliament could be held in anything less than a unified, 32-county Irish state.

Ending abstention was therefore a very controversial issue. In essence, it meant that IRA candidates would be accepting the legitimacy of the Parliaments in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland and therefore accepting partition in principle. A passionate minority believed that such a position would be a rejection of the core value of Irish Republicanism, a united Ireland.

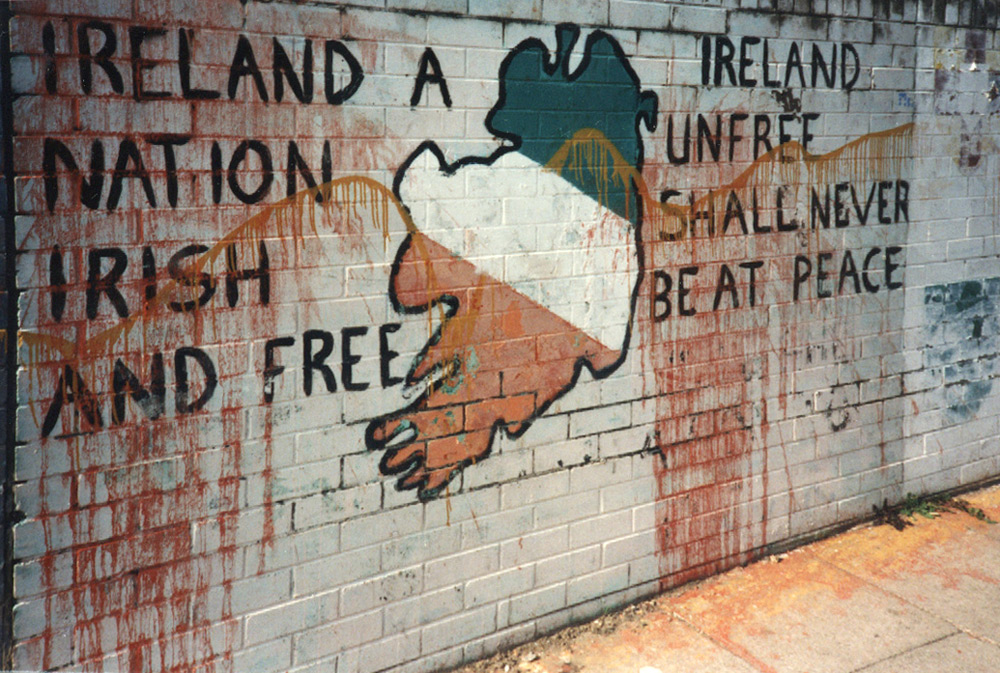

In more practical terms, the dissenters thought that the IRA’s leadership, many of whom were from the south and based in Dublin, completely misread the political situation in the north. The brutal sectarian violence of the previous summer indicated to them that there was no possibility of political reconciliation with Unionists. Instead, they believed that the Catholic community needed defenders and that participation in politics would foreclose the necessary armed struggle.

Originally outvoted 28-12, the dissenters gathered afterward and decided to hold a second convention. The main achievement of this second convention was the election of a seven-man Army Council—Joe Cahill, Leo Martin, Paddy Mulcahy, Sean MacStiofain, Ruari O’Bradaigh, Daithi O’Connell, and Sean Treacy—to lead a reborn IRA, dubbed the Provisional IRA. The majority faction came to be known as the Official IRA.

Shortly afterward, Sinn Fein split along similar lines. Hardline Irish republicanism was now fractured, with the Provisionals confident that they were the only ones who truly represented the Irish nation.

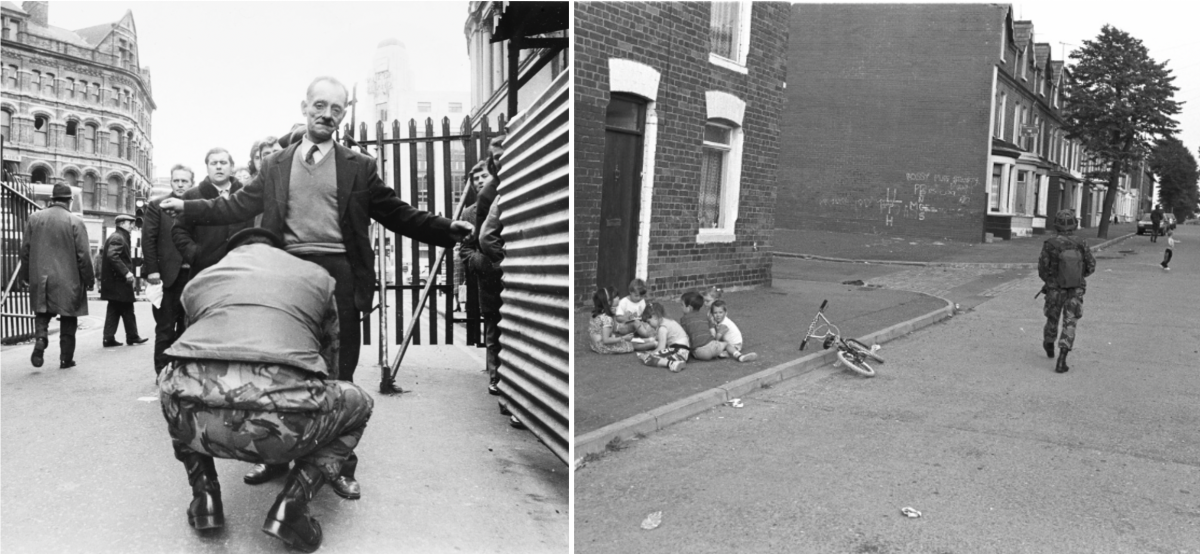

The Provisional IRA grew rapidly and soon eclipsed its predecessor, thanks largely to the poor handling of the crisis in Northern Ireland by the UK government. UK authorities initially tried to solve the problem militarily, by deploying the army in the major cities in Northern Ireland to provide security.

While effective in the short run, the British stopped short of a long-term solution, which would have entailed imposing comprehensive political reforms on the defiant Unionist community. With the political demands of the Catholic community went unanswered, the initially cordial relationship between Catholics and the army broke down, becoming increasingly antagonistic.

A British Army Checkpoint in Belfast, 1977, (left); British soldiers patrol a Belfast street as children play, 1980s (right).

As the Provisionals stepped up their violent campaign to reunify Ireland, the army responded by retaliating against Catholic communities. In 1970, the army began large scale cordon and search operations in Catholic neighborhoods. By 1971, the army was placing Catholic men by the hundreds in indefinite detention without charging them with any crime. Each of these steps drove more and more moderate Catholics into the arms of the Provisional IRA.

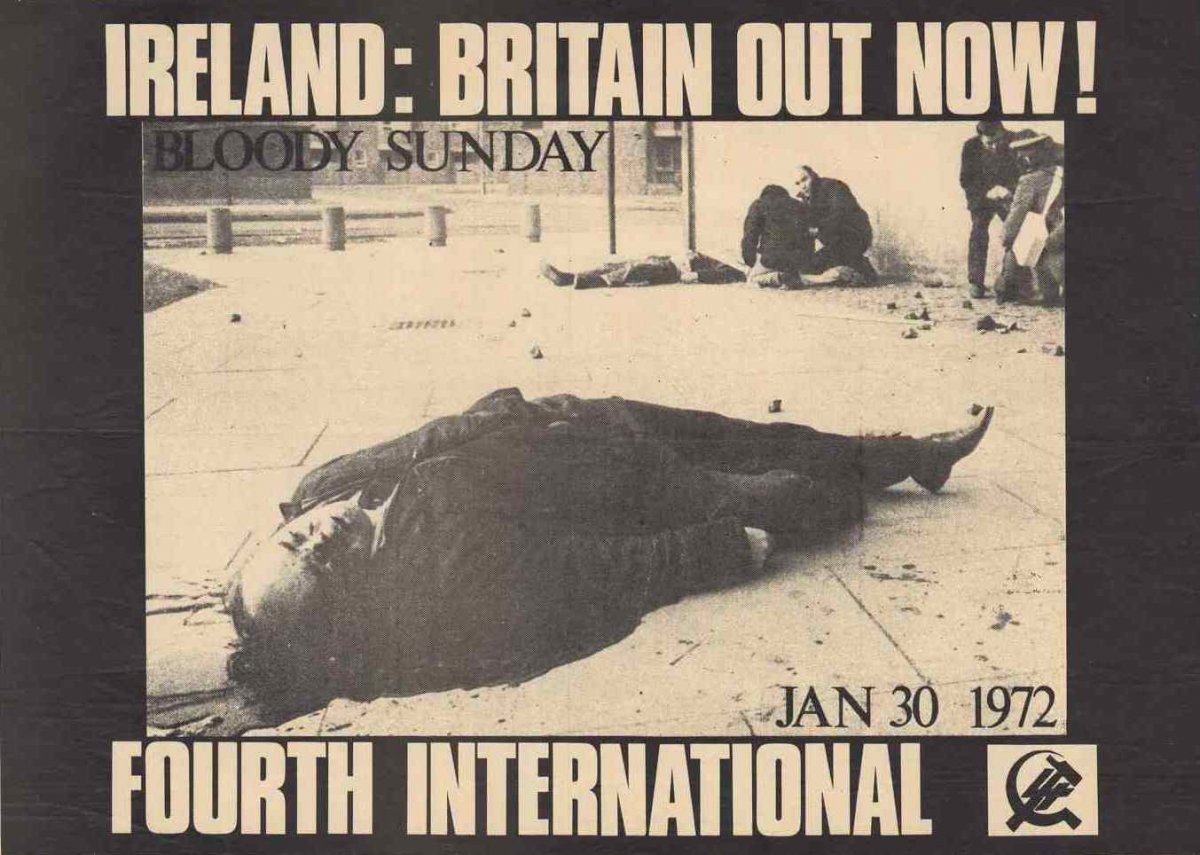

On January 30 1972, British paratroopers massacred Catholic protestors in the aftermath of a civil rights march in the streets of Derry/Londonderry, an event remembered as Bloody Sunday. From that point onward the Provisional IRA’s support was so strong that there could be no possibility of resolving the conflict without its consent.

The tragedy of the situation was that the Catholic people of Northern Ireland needed a political response to the inequality and discrimination they continued to suffer. The Provisional IRA had stepped in as their defenders, but because the identity of the Provisionals was rooted in the rejection of parliamentary politics, they would not help to provide any long-term political answer short of Irish unity.

Militarily, the Provisionals were too weak to defeat the British and unify Ireland. They were, however, strong enough to endure and guarantee that the conflict would drag on, year after year. Not until 1986 would the Provisionals abandon abstention and in doing so finally embark upon the long path that would lead to the resolution of the Troubles in 1998.