“I don’t think they’re done conquering us yet. It just keeps happening.”

—Hugo Sánchez, street vendor of Mexico City, 2006. (Myers, 242)

After a brutal 75-day siege, the Mexica capital of Tenochtitlan surrendered on August 13, 1521. The war cost tens of thousands of lives, civilian and warrior alike. It was a war of atrocity, massacre, and systematic violence. By the end, a few thousand Spaniards under the command of Hernando Cortés fighting alongside many times more Indigenous warriors from places like Tlaxcala and Huexotzinco had destroyed one of the greatest cities of the early modern world, the seat of the Aztec Empire.

Of the devastation, one Nahuatl poem composed several years after gave the following lamentation: “Misery is pouring, misery is felt…tears are pouring, teardrops are raining there in Tlatelolco. The Mexican women have gone into the lagoon…The smoke is rising, the haze is spreading.”

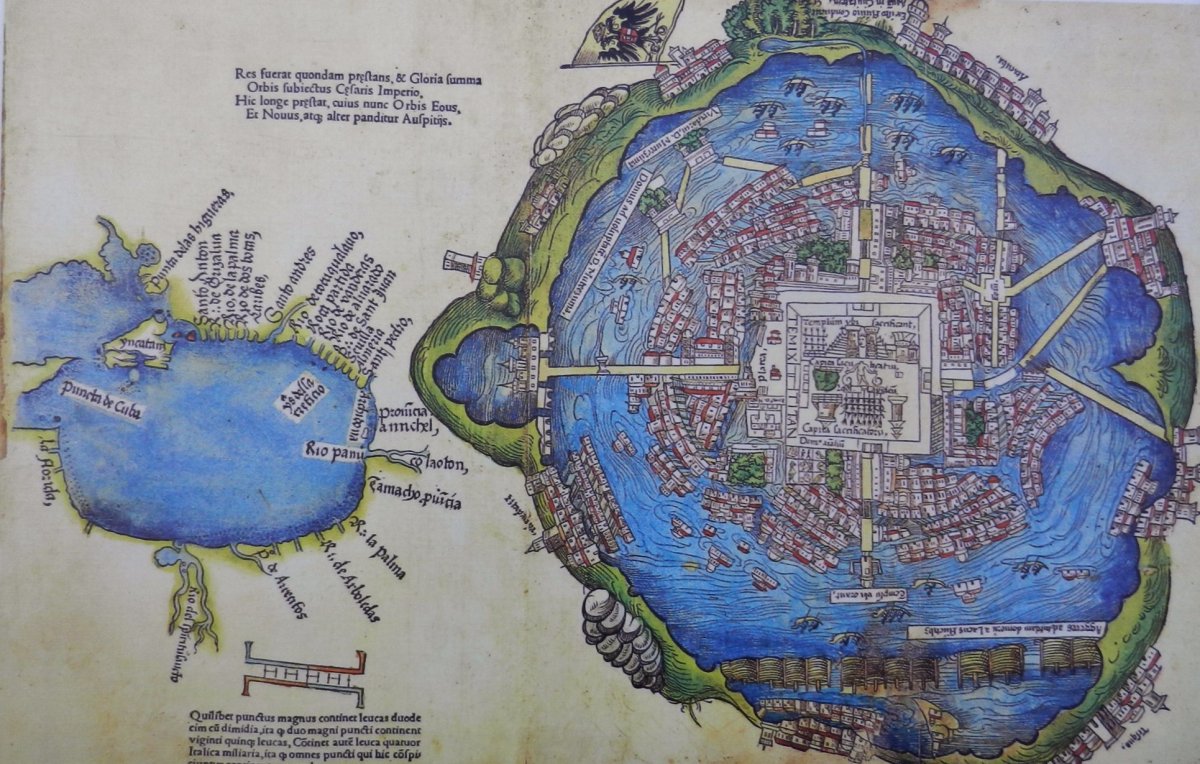

The Nuremburg Map of 1524 is the earliest known European visualization of Tenochtitlan.

Tenochtitlan was constructed on an island in the Valley of Mexico’s Lake Texcoco. Interconnected by canals and causeways and adorned with palaces, temples, marketplaces, and chinampas, Tenochtitlan was home to as many as 200,000 people in the early sixteenth century.

For a Spanish soldier fighting with Hernando Cortés named Bernal Díaz del Castillo, the city’s grandeur defied language. He wrote that upon looking down into the Valley of Mexico, “some of our soldiers asked whether it was not all a dream…It was all so wonderful that I do not know how to describe the first glimpse of things never heard of, seen or dreamed of before.”

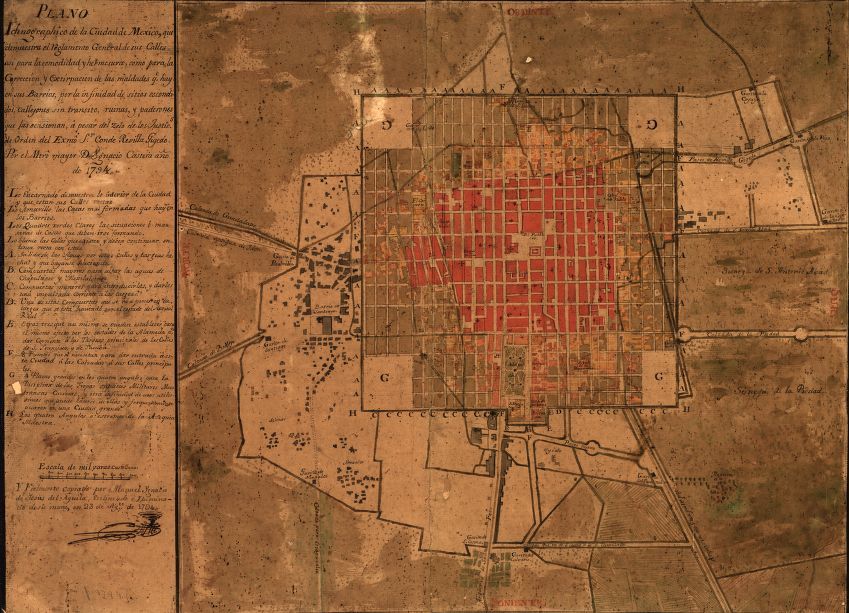

Twenty-one months from that moment, the city lay in ruins. The founding of Mexico City over its ashes continued the violence of the fall. Spanish attempts to control flooding in the Valley emptied and dried the region’s lakes, and a cityscape once dominated by towering pyramids now raised crosses to the heavens.

After 500 years, the story of this monumental, festering trauma is still being written. For scholars of the period, the central task remains fundamentally the same as the 499th anniversary, as the 498th, and so on. We must continue dispelling the tiresome myth that Europeans propagated: that a handful of Spaniards of inherently superior quality to Indigenous peoples in the Americas toppled a tyrannical empire.

This Cortésian fable resonated with generations of Spaniards born too late to share in the bloody plunder of Tenochtitlan. During a Chinese uprising in Spanish-controlled Manila in 1603, the commander Luis Pérez Dasmariñas rallied his troops to launch a counterattack into a larger force on unfamiliar terrain: “What chicken has sung to your ear? Keep going, for 25 soldiers are enough for all of China.”

Dasmariñas quickly learned the hard way that the myth was false. One chronicler recorded what a survivor reported of Dasmariñas’s end: “They came upon him so intently that they crushed him and broke his legs. And on his knees, he fought a long time, until they beat him senseless.”

Artistic rendition of the 1603 massacre of Chinese at the Bahay Tsinoy Museum in Manila, Philippines. Photograph courtesy of the author.

Despite the fatal consequences of this masculine myth of conquest for Dasmariñas and thousands like him, the grand narrative that the fall of Tenochtitlan inspired remains strong today.

In 2006, Kathleen Ann Myers conducted hundreds of interviews along Cortés’s path of invasion into central Mexico, and the results reveal the continuing divide about what happened in 1521 nearly 500 years later. One respondent said the Spaniards “were adventurers who wanted to know more, for scientific or personal reasons, or whatever. And they were good at fighting, very good at fighting. And the men had incredible resolve.” (Myers, 304)

By contrast, another respondent defined the mere idea of a “conquest” as a discourse that silences Indigenous identities, languages, and cultures today. He said, “Anyone who knows history has to agree that what those people [the Spaniards] did when they came to Mexico was a true crime against humanity.”(Myers, 163)

A provocative Mexican film-documentary entitled 499 offers an additional and revealing meditation on what 1521 means today. Directed by Rodrigo Reyes, the piece reexamines contemporary violence in Mexico through the eyes of a sixteenth-century Spaniard washed up on the twenty-first-century coast near Veracruz. Unable to speak, he is condemned to witness and listen to the testimonies of real people entangled in economies of violence today. The film parallels these stories with the Spaniard’s inner reflections of atrocity alongside Cortés, ultimately suggesting that the societal destabilization of invasion has lingered.

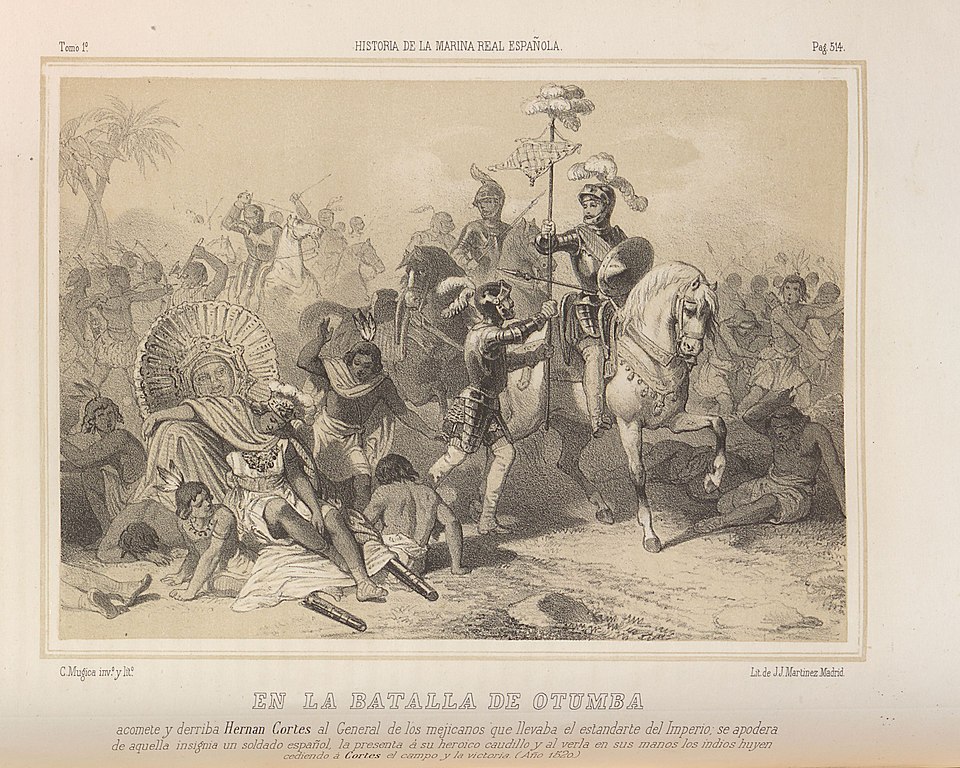

This negotiation of the grand narrative and who gets to control it reaches elsewhere in the digital realm as well. A popular strategy game entitled Medieval II: Total War (2008) revived the heroic narrative of conquest in its presentation of the Battle of Otumba. The Spaniards and their allies retreated towards Tlaxcala after being cast out of Tenochtitlan in the summer of 1520. Montezuma had already been murdered, and an Indigenous coalition trapped the Spanish force on the plains of Otumba and forced a decisive confrontation.

According to the game narration and mechanics, only Spanish cavalry could win the day, transforming Cortés into a hero in the style of a New World Alexander. Notwithstanding, historians have been suggesting since as early as 1958 that Cortés invented the Battle of Otumba to curry favor with the Spanish monarch, Carlos V. Cortés’s contemporaries presented radically different accounts of what supposedly happened at Otumba on July 7, 1520.

Ultimately, the issues of history and narration in the fall of Tenochtitlan underlie every 500-year retrospective on the topic. How does commemoration create grand narratives that resonate over time? How do we, in the twenty-first century, bolster or challenge these narratives with our actions and conversations?

Perhaps the most effective answers would return to the quote that opened this article. Processes of dispossession, environmental destruction, linguistic erasure, religious syncretism, and violent trauma persist in the Valley of Mexico. At the same time, many Indigenous communities maintain a certain autonomy, communal identity, shared history, and ancestral connection to the traumas of 1521.

“Conquer New Worlds” street ad for the Magic Island waterpark in Seville, Spain, summer 2018. Photograph courtesy of the author

Conquest was never complete, and it also never ended, merely shape shifted.

Sources and Suggestions for Further Reading

Kathleen Ann Myers, In the Shadow of Cortés: Conversations Along the Route of Conquest, Pablo García Loaeza and Grady C. Wray, eds., (Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 2015).

Matthew Restall, When Montezuma Met Cortés: The True Story of the Meeting that Changed History, (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2018).

John Bierhorst, trans., Cantares Mexicanos: Songs of the Aztecs (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1985).

Bernal Díaz del Castillo, The Conquest of New Spain, J.M. Cohen, trans., (New York: Penguin Group, 1963).

Bartolomé Leonardo de Argensola, Conqvista delas islas Malvcas, (Madrid: Alonso Martín, 1609), John Carter Brown Library.

Diego Javier Luis, “Rethinking the Battle of Otumba: Entangled Narrations and the Digitization of Colonial Violence,” Rethinking History 23:3 (2019).

Eulalia Guzmán, Relaciones de Hernan Cortes a Carlos V sobre la invasión de Anahuac, vol. 1, (Mexico City: Libros Anáhuac, 1958).

John E. Kicza and Arthur P. Stabler, “Ruy González’s 1553 Letter to Emperor Charles V: An Annotated Translation,” The Americas 42:4 (1986).

Jennifer Gómez Menjívar and Gloria Elizabeth Chacón, eds., Indigenous Interfaces: Spaces, Technology, and Social Networks in Mexico and Central America (Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 2019).

Gilbert M. Joseph and Timothy J. Henderson, eds., The Mexico Reader: History, Culture, Politics, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002).