Last month, French presidential hopeful Emmanuel Macron provoked controversy in France during a visit to Algeria. There, he pronounced French colonialism to have been a “crime against humanity.”

For historians of colonialism, this may not seem like a particularly shocking statement. But in France the image of a presidential candidate making such a declaration in the capital of a former colony whose fight for independence tore France apart over half a century ago was cause for political scandal.

This was particularly true among rightwing politicians and their supporters, a substantial number of whom made up the 800,000 white European settlers (known as pieds-noirs) who fled Algeria in the months immediately preceding independence. For this vocal, but potent minority the real crime was that France, under the leadership of Charles de Gaulle, abandoned the fight to keep Algeria French and sought terms with the Algerian Front de Libération Nationale (National Liberation Front [FLN]).

In their eyes, peace was betrayal.

|

Today, the battle over how to remember those events continues to play out on both sides of the Mediterranean and is directly linked to the agreements signed fifty-five years ago this month between the FLN and the French government to end the Algerian War for Independence.

On Sunday, 18 March 1962 the Algerian War for Independence came to an end. At least, on paper. That paper, simply entitled “Declarations Drawn up in Common Agreement,” was signed in a town on the French side of Lake Geneva better known for its bottled water than its role in diplomatic history: Evian-les-Bains.

Known as the Evian Accords, this settlement called for an immediate ceasefire and ended a seven-and-a-half-year anticolonial war for Algerian independence that has since become immortalized in popular imagination by such cinematic representations as Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers (1966), which celebrated its own anniversary last October. The diplomatic accords laid the groundwork for Algeria’s transition to independence and allowed for post-independence cooperation between Algeria and France.

When independence did come by popular referendum in July 1962, it was seen as having been inevitable. Yet, only a year before the Evian Accords were signed the inevitability of independence seemed far less certain. Peace came only as the product of a long and painful process of negotiation. That the Algerian War was ultimately resolved by a diplomatic agreement was, in itself, a kind of miracle.

Algeria was France’s most entrenched settler colony. Invaded in 1830, the littoral of the colony became an administrative part of metropolitan France in 1848, which made Algiers an older French city than Nice (which was annexed by Napoleon III from the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1860).

When the Algerian War for Independence broke out on 1 November 1954, more than 1 million settlers of European descent (pieds-noirs) lived in Algeria and many of those families had been there for more than four generations. In a common refrain used by supporters of France’s presence in Algeria: Algeria was France. For many in the colony, as well as in Paris, Algeria was an extension of the French nation and giving it up was unthinkable.

After nearly seven years of guerilla warfare and a string of earlier failed attempts at negotiated ceasefires, there was little hope that a diplomatic solution could be found. After all, at the beginning of the conflict French policymakers were confident that the military could quell what were considered to be domestic disturbances by terrorists.

French soldiers patrol the hills above Souk Ahras, Algeria (1958).

On the Algerian side, the FLN had grown from a small clique of revolutionaries uncertain of their ability to win support among the masses to a nationalist movement that had succeeded not only in gaining support internally among Algerian Muslims, but also externally in the court of international opinion. FLN leadership perceived any peace offer from Paris as an attempt to undermine the goal of full independence.

|

1962 propaganda poster in Algiers reading, “The Algerian Revolution, a people at war against colonialist barbarity.” |

Meanwhile, the war took its toll on both sides: French counterinsurgency tactics including torture, large-scale internment, and deadly reprisals against civilians devastated Algeria’s Muslim population. In France, revelations about torture, the ever-increasing demand for young recruits, and growing pressure from the international community to end the conflict eroded popular support for the war.

Many French hoped that de Gaulle would come up with a solution for keeping Algeria French, but it would be de Gaulle who would first seriously consider the possibility of an “Algerian Algeria.” In January 1961, de Gaulle called for a referendum that would authorize the French government to pursue a policy of Algerian self-determination. Two months later, the French government and the FLN began negotiations in Evian. The French delegation was led by Louis Joxe, the Secretary of State for Algerian Affairs, and the Algerians by Krim Belkacem, a Kabyle who had been one of the original six founding members of the FLN.

Negotiations at Evian focused on four main questions about the nature of Algerian independence: guarantees for the pied-noir settler population expected to remain in Algeria; sovereignty over the Sahara (where the French had discovered petroleum deposits in 1956); the status of France’s military bases and its nuclear testing privileges on Algerian soil (the French had detonated their first atomic bomb in the Sahara in 1960); and the framework that would govern future associations between France and an independent Algeria.

The atmosphere at Evian, already tense given the stakes of the negotiations, was heightened by the threat of violence aimed at disrupting the talks by the Organisation de l’Armée Secrète (Secret Army Organization [OAS]), a right-wing paramilitary group formed in February 1961 by disaffected colonial officers and militant pied-noir ultras who vowed to keep Algeria French at all costs.

The danger was real: on 31 March 1961, an OAS commando team assassinated the pacifist mayor of Evian, Camille Blanc, who had lobbied for the negotiations to take place in his city.

Then in April 1961, the conflict in Algeria reached its nadir when a quartet of rogue French generals launched a putsch in Algiers that nearly succeeded in overthrowing President de Gaulle. The plot was foiled, but the incident underscored the extent to which the question of Algerian independence had divided French society.

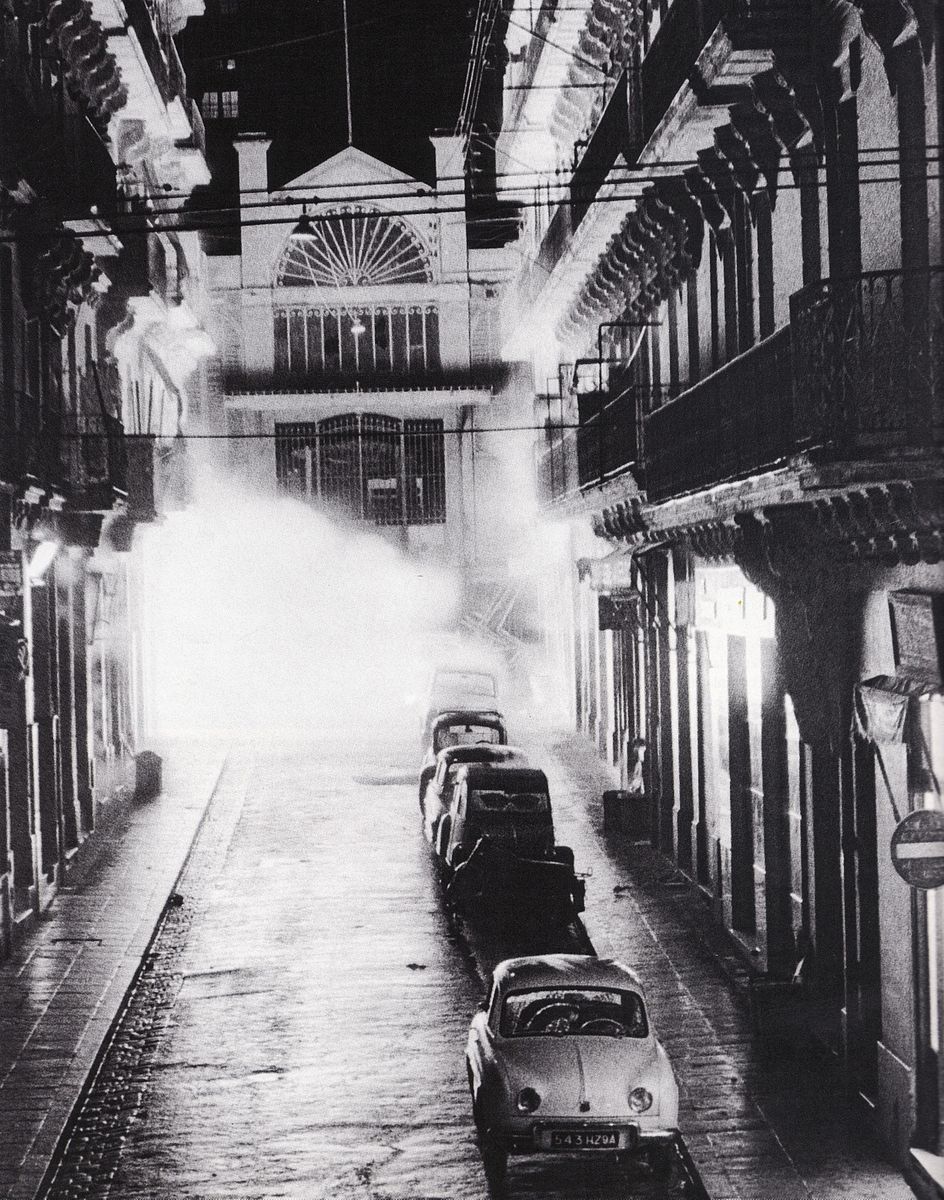

A bomb planted by the OAS explodes in downtown Algiers in January 1962.

After thirteen meetings, the talks at Evian fell apart in June over mutual intransigence to come to any agreement on the future of French settlers or the Algerian Sahara. Peace talks were resumed a month later six kilometers down the road at Lugrin, but these too quickly disintegrated. By the end of summer 1961, a negotiated peace settlement looked impossible.

Yet, for both sides, it became increasingly clear that some agreement had to be reached—lest both the FLN and the de Gaulle administration lose the confidence of their supporters. In December 1961, French and FLN representatives made mutual overtures and agreed to an exchange of documents that highlighted areas of disagreement that had scuttled their previous attempts. They agreed to a new round of secret talks as preliminaries to another meeting at Evian.

Between the end of January and mid-February 1962, French and Algerian negotiators toiled cheek-by-jowl, spending long nights working through the issues of Algeria’s territorial sovereignty, the future of the pieds-noirs, the presence of French military bases, and the main sticking point of the negotiations until that point: the status of the Sahara. Significant progress was made, including France’s willingness to forego claims to the Sahara in exchange for continued French access to petroleum rights.

By 5:00 am on 17 February a rough framework of an agreement had been assembled: a ceasefire followed by a transitional period leading to a vote on self-determination. The rest would be decided at a formal meeting to convene in Evian in early March 1962. This time the negotiators would succeed.

On 7 March 1962, with a late winter storm churning the waters of Lake Geneva, Krim Belkacem and Louis Joxe met once more with their teams at the Hôtel du Parc. For twelve days the negotiations continued, until on 18 March a formal agreement comprising over 90 pages was signed. At noon the next day, military units on both sides were ordered to hold their positions. The fighting stopped. The signing of the Evian Accords assured peace, but an uneasy peace it was.

British diplomatic officials were impressed that de Gaulle managed to extract so much from the Algerians, particularly in matters military. One Foreign Office report called it “a considerable triumph for General de Gaulle,” and de Gaulle had every right to be proud of what his technocrats were able to negotiate at Evian.

For their part, the Algerians had remained steadfast while negotiating and succeeded in wearing down initial French ambitions. Yet, the content of the Evian Accords almost immediately provoked controversy on both sides: in France, hardliners thought their countrymen had given up too much, while in Algeria, more radical factions of the FLN believed that Krim Belkacem and his negotiators had received too little and decried the accords a neo-colonial Trojan horse.

Episodes of violence severely tested the Evian ceasefire, but the provisional government and mixed ceasefire commissions managed to stave off the resumption of open hostilities between France and the FLN and assured that the referendum on self-determination took place in relative calm.

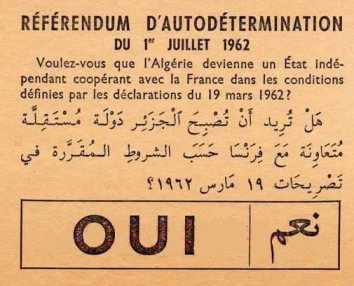

Scheduled for 1 July 1962, residents of Algeria were asked: “Do you want Algeria to become an independent state, co-operating with France under the conditions defined in the declarations of 19 March 1962?” By the end of the day 5,975,581 to 16,534 voted in favor. Two days later, at 10:30 a.m., Charles de Gaulle announced the French Republic’s official recognition of Algerian sovereignty.

Ballot marked “yes” used in the referendum on Algerian self-determination, held on 1 July 1962.

By 3 July 1962, the war had taken the lives of over 300,000 Algerians and mobilized almost 1.5 million French soldiers. Today, the specter of colonialism—further complicated by the dynamics of postcolonial immigration and messy economic entanglements—continues to haunt both Algerian and French societies. And debates over the legacy of French decolonization in Algeria remain fraught with the perils of a living memory barely fifty years old.

These days, the Evian Accords are seen as a sincere, if flawed attempt to bring peace to a conflict destined to end badly. But the Evian Accords brought an end to a nearly eight-year war of attrition and allowed for cooperation to continue between the two nations.

Perhaps now more than ever, the history of the Evian Accords underscores the importance of compromise and pragmatism, even in the face of impossible odds and intractable interests.

Ceremony in France marking the 50th anniversary of the Evian ceasefire agreement in March 2012.