Zimbabwe, formerly Southern Rhodesia, gained independence from British colonialism on April 18, 1980. The nation commemorates this political milestone annually, with the president attending the main event in Harare, the capital.

Despite these political celebrations, Zimbabwe continues to grapple with the international community over land questions, which are rooted in the British conquest in 1890 and have shaped its national politics and economic relations with the West since 2000.

Britain’s formal colonization took place nearly 6 years after the landmark Berlin Conference convened in 1884-85. At that meeting, the European powers carved the African continent among themselves based on their strategic, economic, and political interests. The General Act of Berlin ratified colonization by establishing the principles of “effective occupation” and “sphere of influence” that guided their colonial claims.

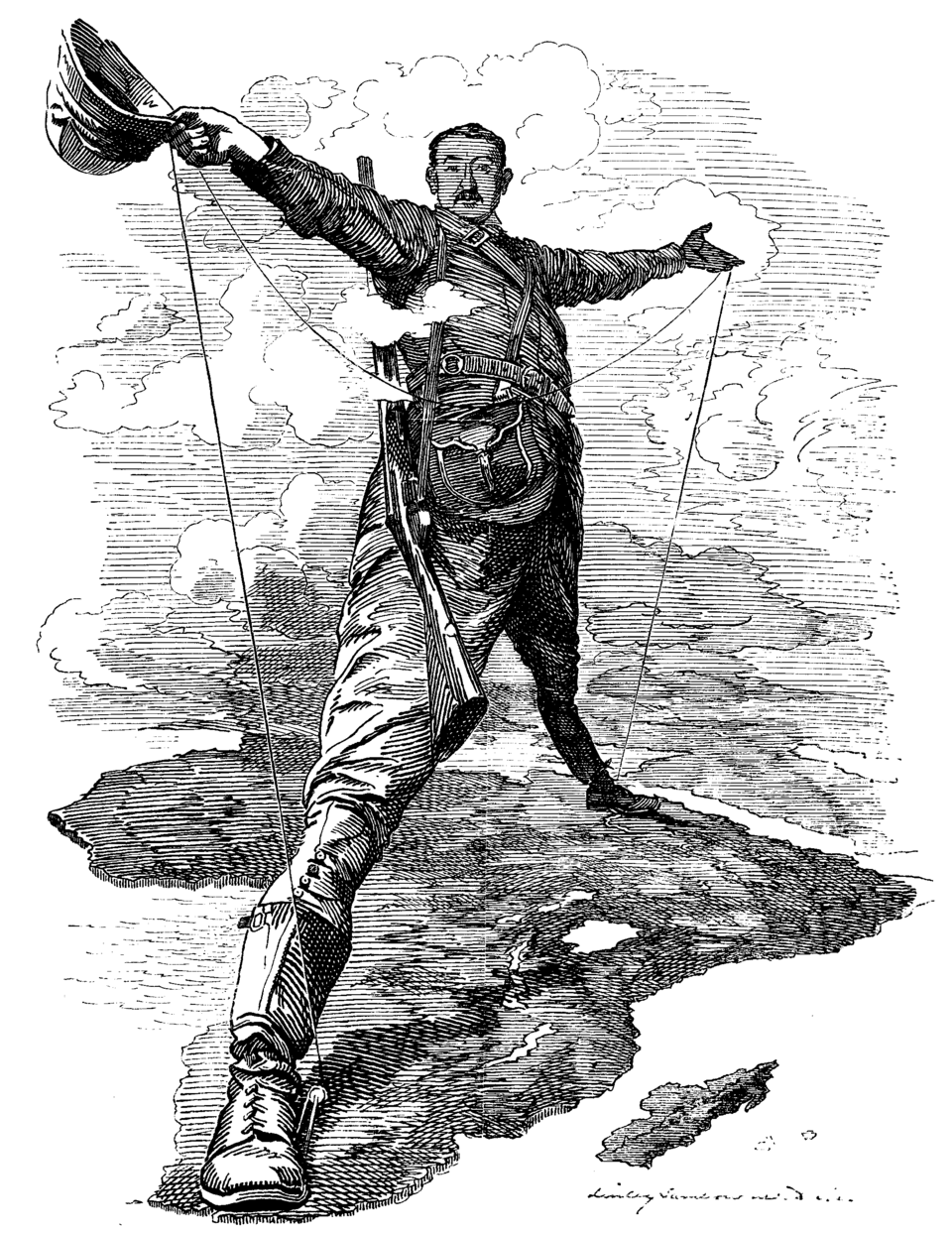

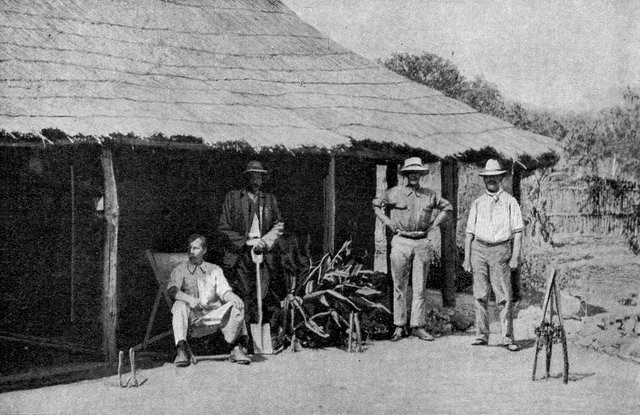

Zimbabwe fell into the British sphere of influence before the British South Africa Company (BSAC), led by Cecil John Rhodes, effectively occupied the territory on September 12, 1890, and raised the Union Jack flag to symbolize British control over its fertile land and mineral-endowed deposits.

The BSAC named the territory Rhodesia in honor of Rhodes, who financed the colonization project. The Pioneer Column, a unit of British soldiers and settlers, administered the occupation of Zimbabwean territory by the BSAC.

The BSAC’s northward expansion resulted from Rhodes’ desire to control the region’s fertile land and mineral-endowed deposits following the discovery of diamonds and gold in South Africa in the late 1800s. Rhodes demonstrated his imperial ambitions when he planned to establish a Cape to Cairo railway & telegraph line that connected British territories from South Africa to Egypt.

The occupation of Zimbabwe in 1890 gave Rhodes and his British South Africa Company exclusive rights to practice mining, hunting, and farming. The colonial administration enacted legislation that deprived the indigenous people of access to the land they had owned for centuries.

Realizing they had lost their independence, the Ndebele kingdom, under King Lobengula, declared war against the British, initiating the first organized African resistance in what is known as the Anglo-Ndebele War (or First Matebele War) of 1893. However, their efforts were futile due to the superiority of colonial weaponry coupled with a lack of unity among the indigenous people.

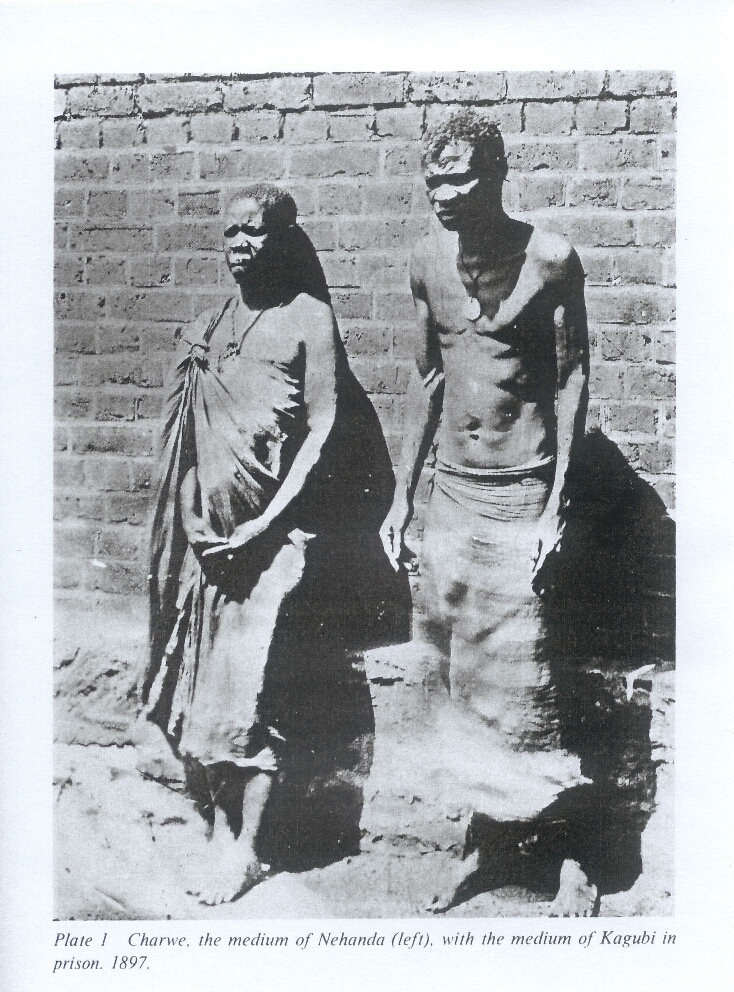

The Shona, the dominant ethnic group, also declared war to reclaim their freedom from the BSAC in the popular First Chimurenga (struggle) of 1896-98. The lack of unity between the Shona people and the Ndebele led to defeat by the British, and the execution of two spirit mediums, Nehanda Nyakasikana and Sekuru Kaguvi, who had organized the revolts against the British South Africa Company.

Ultimately, the First Chimurenga of 1896 inspired the Second Chimurenga (liberation struggle) of 1972-80, which liberated Zimbabwe from colonialism.

In 1898, the colonial administration enacted the Native Reserve Order, a mass expropriation of fertile land from the indigenous people, and the subsequent creation of resettlements for blacks called Native Reserves.

In 1930, the Southern Rhodesian government passed the infamous Land Apportionment Act (LAA), a segregationist legislation that allocated land along racial lines. The most productive land was granted to white settlers, a small minority, while the majority of Africans were restricted to infertile lands in the native reserves.

The colonial administration intensified the dispossession of land from Africans by passing the Native Land Husbandry Act in 1951. The NLHA resulted in compulsory livestock destocking and downsizing of land owned by Africans to avoid overgrazing and degradation of land.

The rationale was not to regulate the land use but to impoverish Africans to force them into wage labor on white-owned farms. The land alienation policies intensified with the passing of the Land Tenure Act in 1969 by the new pro-white minority administration under Ian Douglas Smith, which openly opposed any African political and economic rights.

The intensification of colonial legislation under the Smith regime instigated African political activism, culminating in the liberation war. The formation of the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU) in 1962 and the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) in 1963 were watershed moments in the history of Zimbabwe. With the support of the Eastern Bloc at the height of the Cold War, ZAPU and ZANU militarily engaged the Rhodesian government in a bloody civil war that ended in 1979.

The Lancaster House Agreement, signed on December 21, 1979, concluded the war and nullified Rhodesia’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence that jeopardized black majority rule. Mugabe’s ZANU party resoundingly won the fresh elections observed by the international community.

Despite this political victory, Mugabe's administration still had no control over the land.

The Lancaster Agreement had a clause on land reform under the willing-buyer, willing-seller principle. White farmers would willingly sell land to the Zimbabwean government, and the government would buy it at market prices with funds donated by the British government.

The provision prohibited land seizures from white farmers for almost two decades until Mugabe launched the controversial Fast Track Land Reform Program (FTLRP) in 2000. To landless Zimbabweans, the FTLRP was a way to achieve the economic independence they had long awaited.

However, the international community condemned the FTLRP, citing violent land seizures, human rights abuses, and violations of property rights and the Lancaster House Agreement. Global leaders subsequently imposed economic sanctions on Zimbabwe that brought the economy to its knees for over two decades.

Zimbabwe’s FTLRP significantly affected South Africa. The program inspired radical political movements such as Julius Malema’s Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) party, which advocates for a radical redistribution of land in South Africa. They deem economic independence to be the total ownership of the means of production by the formerly colonized majority.

The South African government recently signed into law the Land Expropriation Act, legalizing the state to seize land from commercial white farmers without compensation. This act prompted an aggressive response from the Trump Administration, which cited gross human rights violations in South Africa.

The land question in Southern Africa continues to shape the economic relations between African states and the international community, with the former viewing it as a necessary step to correct the colonial justices. At the same time, the latter take the matter as a threat to their interests, framing their concerns around violations of human rights, economic stability, and legal protections.

![]()

Learn More

Rotberg, R. The Founder: Cecil John Rhodes and the Pursuit of Power, (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1988)

Ranger, T.O. Revolt in Southern Africa, 1896-7 (Northwestern University Press, 1967)

Stedman S. J The Lancaster House Constitutional Conference on Rhodesia, (Pew Charitable Trust, 1988)

Hanlon, J., Manjengwa, J.M., & Smart T., Zimbabwe Takes Back Its Land, (Kumarian Press, 2013)