Like its neighbor South Africa, Zimbabwe emerged from colonial and white minority rule at the end of the last century. And since independence both countries have experienced single-party rule. In 2024, however, South Africans voted a new party into power while Zimbabwe remains in the grip of the ZANU-PF. This month Luke Marara examines the recent history of Zimbabwe and compares it to South Africa's to ask why the former hasn't developed like the latter.

The 2024 elections in South Africa marked a significant shift in the country’s political landscape, as the dominant African National Congress (ANC) failed to secure a majority vote, leading to the formation of a Government of National Unity (GNU) for the first time since 1994.

The same had occurred in Zimbabwe, formerly Southern Rhodesia, in 2008 when the dominant ZANU-PF party failed to secure a majority vote for the first time since independence in 1980. A coalition government was also formed between ZANU-PF and the main opposition party, Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), which lasted from 2009 to 2013.

South Africa, in fact, played a pivotal role in mediating the negotiations between ZANU-PF and the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC). Now the country might learn from the history of its northern neighbor, which has tried to balance multiparty rule for more than 15 years.

From Colony to White Minority Rule

The path to Zimbabwe’s independence from colonial control was not smooth. Unlike other countries such as Botswana, Zambia, Lesotho, and Swaziland (now Kingdom of Eswatini), all of which transitioned to independence through peaceful processes in the 1960s, resistance organizations had to engage the Rhodesian government in a lengthy and bloody civil war that lasted almost 15 years, from 1965 to official independence in 1980.

Political factors complicated matters. Since the early 1960s, the British government had been nudging Rhodesia’s white minority government to transition to black majority rule. This proposal was rejected by Prime Minister Ian Douglas Smith, who had assumed office in 1964.

Smith subsequently announced what is known as the Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) on November 11, 1965. The UDI called for cutting ties with Britain while maintaining white minority rule, a move that was condemned by the international community. In response, members of the United Nations (UN) imposed sanctions and increased diplomatic pressure on the government.

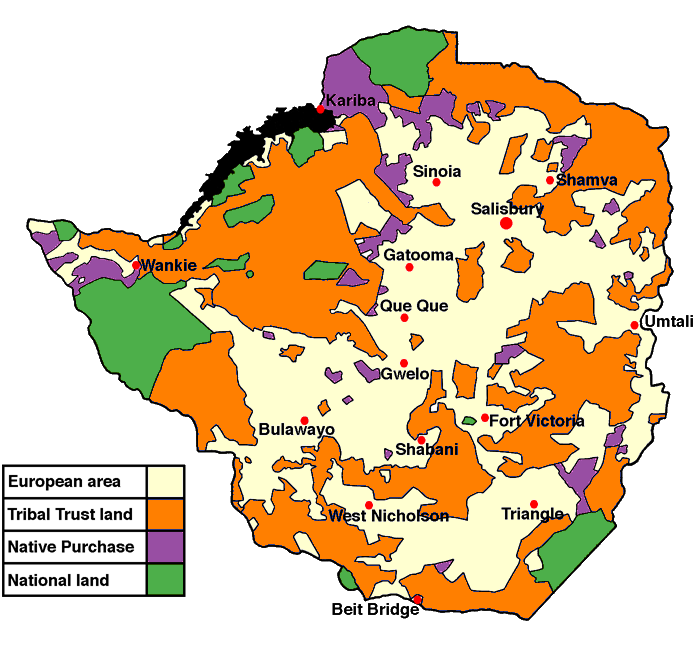

Smith adopted and implemented discriminatory government policies closer to those enforced by the apartheid regime in South Africa. The policies were designed to maintain white minority control over a black majority population.

He made his infamous speech: “I don’t believe in black majority rule ever in Rhodesia – not in a thousand years. I repeat that I believe in blacks and whites working together. If one day it is white, the next day it is black, I believe we have failed, and I think it will be a disaster for Rhodesia.”

Minority rule in Rhodesia was doomed, however, given the internal and external pressure the government was facing. Externally, the international community continued to isolate the colony through economic sanctions and diplomatic pressure. Internally, we saw the birth of many nationalist movements and political parties fighting for independence.

The Path to Independence

From the late 1950s, political parties were formed, but they were short-lived because the Rhodesian government could pass legislation that outlawed the formation of anti-colonial political parties. However, the nationalists did not give up, forming political parties one after the other.

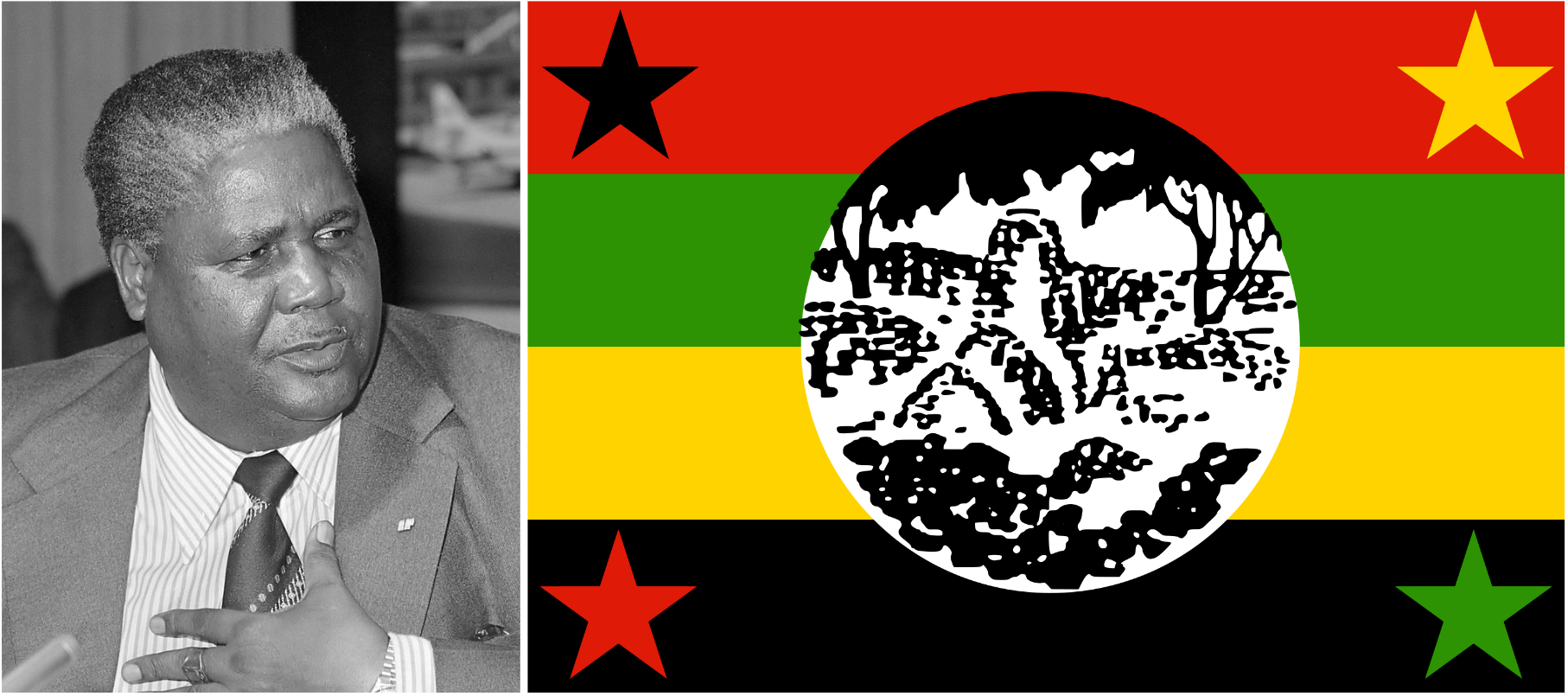

Zimbabwe’s popular nationalist, Joshua Nkomo, who later became vice president, formed a series of political parties in the late 1950s following the banning of each one by the colonial government.

The banning of the Southern Rhodesia African National Congress (SRANC) in the late 1950s led to the formation of National Democratic Party (NDP) in 1961. When the NDP was banned, Nkomo regrouped as Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU), a socialist-aligned political party that contributed significantly to the liberation of Zimbabwe in 1980.

In his quest for independence, Nkomo did not go it alone. He had fellow comrades including the future president, Robert Gabriel Mugabe, and Ndabaningi Sithole, one of the founders of the Zimbabwe African National Union - Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) in 1963 when ZAPU split.

Various theories are put forward to explain the ZAPU-ZANU split, a rupture between two leading political parties that won Zimbabwe’s independence in 1980.

There are historians who argue that the split was based on ethnic lines. Nkomo was ethnically Ndebele, the second most dominant ethnic group after the Shona. Robert Mugabe, on the other hand, was Shona. Yet both parties drew from both Ndebele and Shona ethnic groups.

Other historians believe that the ZAPU-ZANU split was a result of ideological differences between the two parties. From the beginning, Nkomo advocated for peaceful resolutions including negotiations and industrial action, renouncing a violent struggle for independence. To the contrary, Mugabe and his ZANU-PF comrades openly advocated for violent confrontation with the colonial government from the outset.

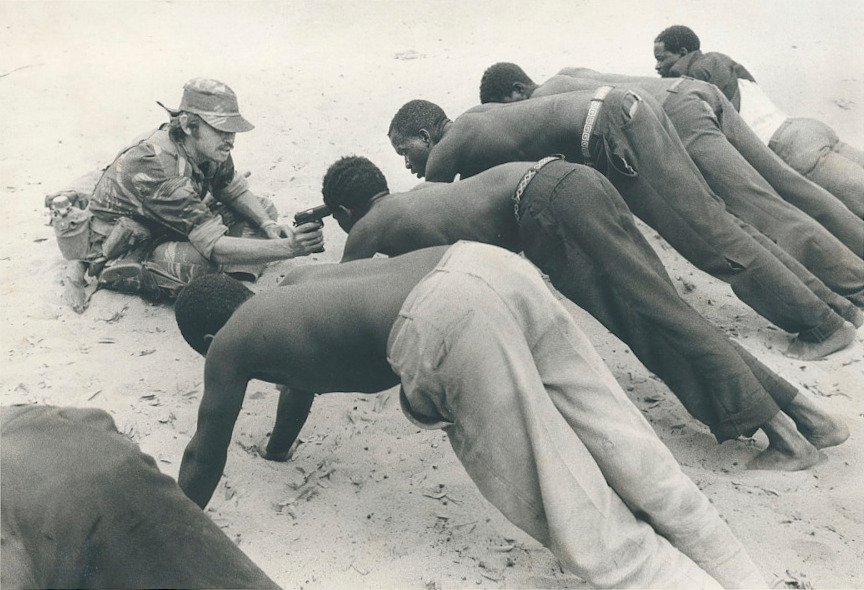

From 1964 on, following the intensification of political repression by Ian Smith’s government, ZANU adopted violent tactics, including sabotage, bombing of trains and railways, attacks on electric power plants, and murders of white farmers on their remote farms.

The same was happening in South Africa where anti-apartheid movements led by Nelson Mandela had resorted to a violent campaign following an escalation of brutality by the apartheid regime.

At the time, Mozambique to the east was also embroiled in a lengthy civil war against the Portuguese colonial government. It attained its independence in 1975 following a protracted and bloody civil war. The independence of Mozambique was critical to the independence of Zimbabwe because it provided a strategic military base for their nationalist movements.

After conducting military operations in Rhodesia, nationalists could retreat into now independent Mozambique and Zambia, which had attained its independence from British colonial rule on October 24, 1964.

The liberation struggle of Zimbabwe reached its climax in 1978 when the Rhodesian government engaged ZANU and ZAPU in a bloody direct confrontation. If ZANU and ZAPU had been united, the struggle might have been less protracted. Each nationalist movement was riven by factionalism, and struggles for power rocked them from within. Still, they continued to fight for independence.

The Rhodesian Bush War was concluded on December 21, 1979, after a diplomatic conference in London resulted in the negotiation of the Lancaster House Agreement, which included terms for creating a post-independence Zimbabwe.

Leaders of various political parties including Joshua Nkomo (ZAPU), Robert Mugabe (ZANU-PF), and Bishop Abel Muzorewa of the United African National Council (UANC) gathered around the negotiation table to map the future of Zimbabwe.

Muzorewa had formed a short-lived coalition government with the white minority Rhodesian government from June 1, 1979 to April 18, 1980. However, the international community refused to recognize the coalition because it did not represent majority rule.

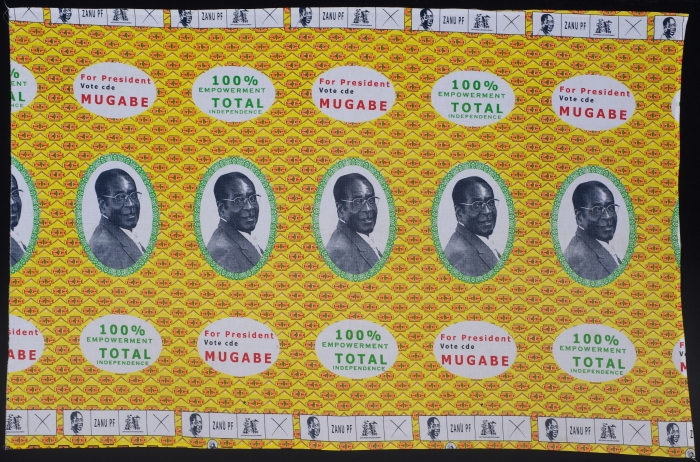

Under the terms of the Lancaster House Agreement, general elections were held in February 1980, and Mugabe’s ZANU-PF party won 63% of the vote. Mugabe became the first prime minister of independent Zimbabwe, and Canaan Banana became its first president, a largely ceremonial position under the constitutional framework established at independence, which vested all the executive powers in the prime minister.

Post-Independence Zimbabwe and Regional Challenges

Zimbabwe’s independence in 1980 came with its own challenges. Most important was the threat posed by the apartheid regime in South Africa, which lasted until 1994. The South African government was concerned that the influence of independent southern African states like Zimbabwe would fuel similar efforts at home. They knew that the wave of independence was not going to spare their own regime.

In a preemptive move, the regime implemented the infamous Destabilization Policy (1960-1990), designed to weaken and destabilize independent countries that could assist anti-apartheid movements in South Africa, such as Angola, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Zambia, and Botswana.

Through a series of covert operations, the apartheid government provided support to rebels and opposition groups to undermine the governments of their independent neighbors. The Destabilization Policy resulted in regional instability as countries such as Mozambique and Angola became embroiled in lengthy civil wars sponsored by apartheid South Africa and the Western bloc during the Cold War.

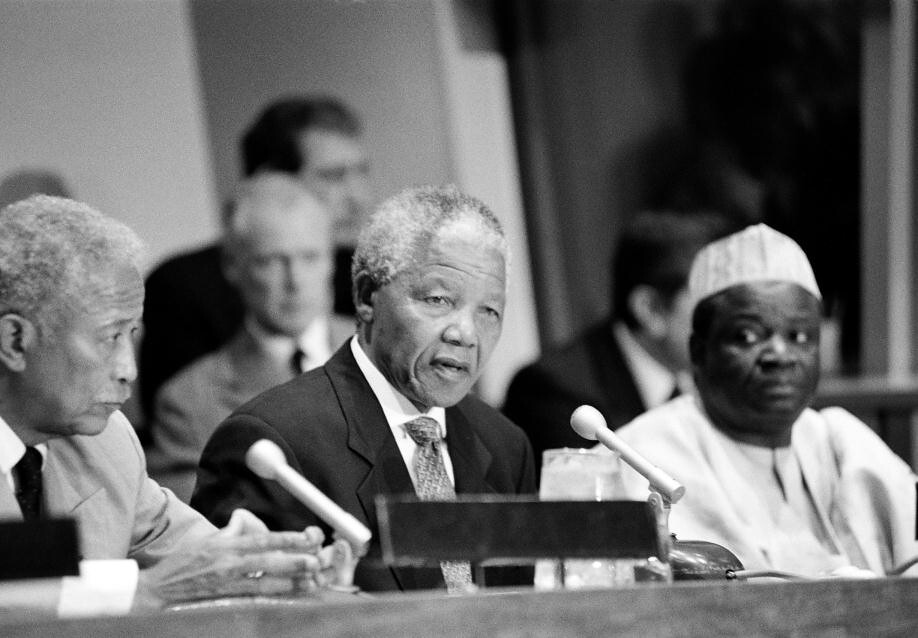

Following the end of the Cold War in 1991, regional and diplomatic isolation and internal pressure from nationalist movements such as African National Congress (ANC), Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), and Umkhonto weSizwe (MK), the apartheid regime finally collapsed in 1994. This was a watershed moment in the history of South Africa as the first democratic, multiracial elections were held.

The African National Congress led by Nelson Mandela won a decisive victory, securing nearly 63% of the vote. Despite this victory, the ANC had to form a Government of National Unity with IFP, which received 10%, and the National Party (NP), which received 20%. Mandela was the first black president of the Republic of South Africa (RSA) from 1994 to 1999.

Zimbabwe and South Africa have shared somewhat parallel political and historical trajectories. The two nations have had their first democratic, multiracial elections after a long struggle against white minority governments that were reluctant to yield to a majority rule. The historic elections held in these two countries resulted in black majority rule, followed by the establishment of coalition governments.

When Mugabe’s ZANU-PF resoundingly won the elections in 1980, a government of national unity was also formed with Nkomo’s ZAPU, with the latter becoming the minister of home affairs.

From Unity Governments to Single Party Rule

The post-independence period in Zimbabwe and South Africa was marked by an ever-growing support for, and dominance by, the liberation movements, ANC & ZANU-PF respectively, which won electoral victories in their subsequent elections. Their dominance was deeply rooted in their historical role in the struggle against racial segregation and minority rule.

In Zimbabwe, the rivalry between two liberation movements, ZANU-PF and ZAPU escalated after independence despite a Government of National Unity they had agreed to establish at independence. Political violence and instability rocked Zimbabwe, reflecting a simmering power struggle between the two main liberation movements predating independence.

The power struggle between ZANU-PF and ZAPU resulted in the consolidation of power by the ZANU-PF party through the Unity Accord signed by Nkomo and Mugabe on December 22, 1987. The Accord facilitated a merger that combined ZANU-PF and ZAPU into a single party. The constitutional amendment in the same year abolished the office of the prime minister, and Mugabe assumed the presidency.

Under the new arrangement, Nkomo joined Mugabe as one of his two vice presidents. The accord ended ethnopolitical violence and subsequently fostered national unity, peace, and reconciliation between the two political parties. This was a political victory for Mugabe, for he had managed to neutralize what he considered to be the biggest political rivalry to his rule since independence.

South Africa and Zimbabwe continue to draw lessons and influence from each other. The Unity Accord of 1987 provided crucial lessons on the need for peace and reconciliation if a country is committed to national unity, nation-building, and economic development.

Mandela gained significant political mileage following his remarkable commitment to forgiveness, peace, and reconciliation with his former captors who had detained him for 27 years.

Mugabe and Nkomo had successfully set a stage for reconciliation towards national and regional peace and development. The absorption of ZAPU, however, meant the death of opposition politics for a while, and Zimbabwe was set for unofficial one-party rule.

This was reflected in the 1990 elections when Mugabe won resoundingly against his former liberation comrades, Edgar Tekere of Zimbabwe Unity Movement (ZUM) and Ndabaningi Sithole of ZANU-Ndonga.

In the election, out of 120 contested seats, Mugabe’s ZANU-PF party garnered 117 seats, ZUM won 2 seats and ZANU-Ndonga won a single seat. The elections in 1995 finally sealed the fate of opposition politics during that decade. ZANU-PF won 118 seats against ZANU-Ndonga’s 2 seats, securing another uncontested tenure in office. These electoral results highlighted a total political eclipse of opposition politics by ZANU-PF, leaving little or no room for dissenting voices.

The Emergence of Contested Politics: Zimbabwe’s Path to GNU

It was not until 2000, 20 years after he came to power, that Mugabe first faced meaningful opposition. ZANU-PF suffered its first electoral defeat in a constitutional referendum to the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), led by Morgan Tsvangirai, as 55% voted “NO” against the government’s proposed constitutional amendment.

MDC was formed in September 1999, marking a historic turning point in the political history of Zimbabwe. It was a formidable opposition party and transformed the political landscape of Zimbabwe. The MDC advocated for democratic reforms, human rights, and economic policies that were different from those of the ruling party.

The MDC had its roots in the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Union (ZCTU) led by Morgan Tsvangirai. The ZCTU was a labor organization that had represented workers since independence. As its leader, Tsvangirai developed good relations with the working class across the country. At the same time, his relationship with the government deteriorated, which led him to break away and form his political party which ended the dominance of a single political party.

The formation of MDC triggered the intensification of the Fast Track Land Reform Program (FTLRP) in 2000. Fearing another defeat in the upcoming parliamentary elections in June 2000, the ruling party embarked on an unprecedented, radical land reform program meant to redress the historical imbalances that had been facilitated by colonialism. More than 10 million hectares of land were confiscated from about 4000 white commercial farmers and redistributed to hundreds of thousands of blacks across the country between 2000 and 2002.

The impact of the MDC party became evident in the 2008 elections when the ruling party failed to secure a majority vote for the first time in the post-independence era. Robert Mugabe of ZANU-PF received 43.2% of the vote, while Morgan Tsvangirai of the MDC party garnered 47.9% of the vote.

No candidate received an outright majority and the result was a runoff on June 27, 2008. However, Tsvangirai withdrew from the runoff citing widespread state-sponsored political violence against his supporters. Mugabe declared himself the winner in an uncontested runoff but the result was internationally condemned.

The disputed election results led to the negotiations brokered by former South African president, Thabo Mbeki. This resulted in the historic formation of a Government of National Unity on February 11, 2009.

ZANU-PF had to share political power, for the first time since 1980, with Morgan Tsvangirai’s MDC-T (Tsvangirai) and Professor Arthur Mutambara’s MDC-M (Mutambara) that had split shortly before the elections. In the new government of national unity, Mugabe retained the presidency but shared his executive powers with Prime Minister Tsvangirai who was deputized by Prof. Mutambara.

The coalition brought political and economic stability. The hyperinflation that had severely disrupted Zimbabwe since the turn of the millennium came to an end through the dollarization of the economy. The country, under new Finance Minister Tendai Biti of the MDC-T party, adopted a multicurrency system that allowed the use of foreign currencies like the U.S. dollar, the South African rand, and Botswana’s pula, for all transactions. The U.S. dollar became the most commonly used currency following Prime Minister Tsvangirai’s visit to the U.S. in 2009, and it has remained so to date.

The Government of National Unity brought far-reaching positive socioeconomic impacts in Zimbabwe, highlighting the importance of political unity in fostering economic development.

The recent Government of National Unity in South Africa has much to learn from Zimbabwe’s 2009-2013 experience, particularly in how political collaboration can positively drive economic progress and nation-building. There is no historical moment that Zimbabweans cherish more than the GNU era, which brought political stability and economic development that remains today.

The period that followed post-GNU in Zimbabwe highlighted a renewal of political tensions between the ruling party and the MDC party. The era was also marked by economic uncertainty characterized by unemployment, inflation, and currency instability. Reflecting on Zimbabwe’s post-GNU period can offer valuable insights and cautionary lessons for South Africa, and the southern African region at large, in navigating their own political and economic challenges.

Lessons drawn from Zimbabwe and South Africa’s historical and political trajectories highlight the importance of robust democratic institutions, political collaborations, and peace and reconciliation in multi-party democracies across the African continent. Zimbabwe’s political history offers valuable insights into how political polarization can stifle economic progress. In light of Zimbabwe’s post-independence political history, it is evident that political collaboration unlocks economic development and stability.

Masipula, S. Zimbabwe: Struggles within the Struggle. (Salisbury: Rujeko Publishers, 1979)

Masunungure, E. “Travails of Opposition Politics in Zimbabwe since Independence,” in D.H Barry (Eds), Zimbabwe: The Past is the Future (Harare, Weaver Press, 2004).

Noyes H. Alexander, A New Zimbabwe? Assessing Continuity and Change After Mugabe (Rand Corporation, 2020)

Raftopoulos, Brian, Reflections on Opposition Politics in Zimbabwe: The Politics of MDC, (University of Western Cape, 2013).

Sadomba, W. A. Decade of Zimbabwe’s Land Revolution: The Politics of War Veteran Vanguard, (James Currey & Harare, Weaver Press, 2011).