On March 20, 2003, a U.S.-led coalition invaded Iraq. A decade on, how do we—and how should we—remember this war?

Tactically, it was one of the most successful military operations in history, but many Americans will not remember the war as an overwhelming victory. Within only twenty-one days’ time, an enemy army of some 400,000 men dissipated in the face of an invasion force just over half its size. The coalition ended an oppressive, murderous regime and occupied the country at the cost of approximately 155 U.S. soldiers killed. Yet, despite this initial military success, Americans are more likely to remember it as a tragic war—a near loss at best, a debacle at worst.

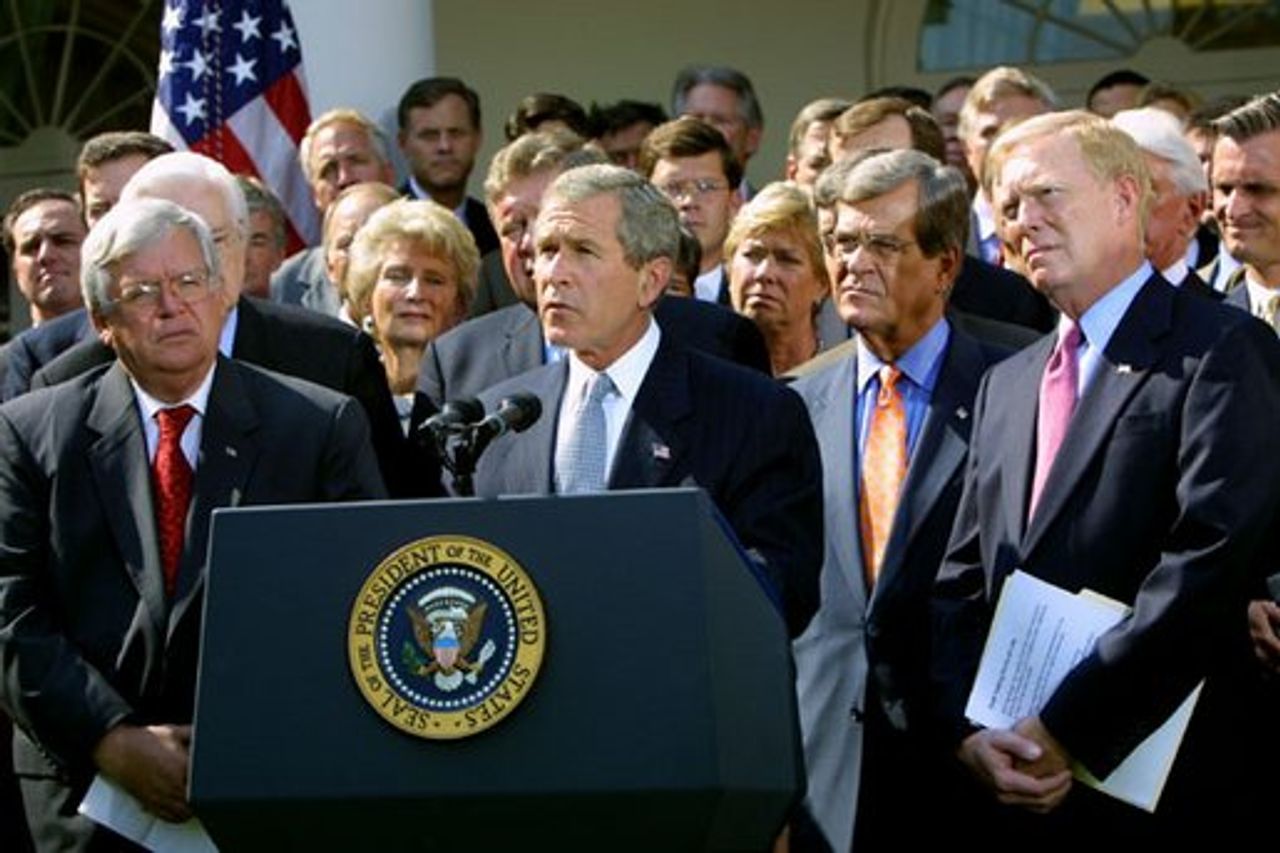

It will also likely be remembered as George W. Bush’s war: a war that he initiated almost unilaterally, with a willful misleading of the public, and a war that committed a democratic nation’s armed forces to a strategically disastrous regime-changing invasion. To color the war in such a way may be emotionally satisfying, but it oversimplifies a much more complicated picture. All three branches of the U.S. government within its system of checks and balances approved the war and, as a poll from the Pew Research Center indicates, a majority of Americans cheered as the first bombs fell.

President Bush’s decision to invade Iraq was first approved in Congress and then upheld in federal court.

In October 2002, the U.S. Congress passed the Iraq War Resolution, authorizing the President to use military force against Saddam Hussein.

In the February 2003 lawsuit Doe v. Bush, which attempted to strike down the Iraq War Resolution as unconstitutional, the plaintiffs cited Thomas Jefferson and argued that a formal congressional declaration of war is beneficial because it “slow[s] the ‘dogs of war’…Congress, the voice of the people, should make this momentous decision.”

The plaintiffs’ rhetoric was ironic in two ways. For one, Thomas Jefferson was the first U.S. president to commit military forces to the Middle East without a formal declaration of war. Undeclared wars are not therefore recent in U.S. history, nor is it clear that they are contrary to the Founding Fathers’ intent. Second, the plaintiffs failed to realize that Congress, the voice of the people, had indeed made the momentous decision by approving Bush’s resolution.

The U.S. First Circuit Court of Appeals summarily struck down Doe v. Bush, thus ruling the Iraq War constitutional. President Bush continued to press his case for war now that he was legally unfettered, despite flagging U.N. support and deteriorating international popular opinion. In the late evening of March 19, 2003, he announced the beginning of the invasion that Congress had authorized.

In a rush of patriotic enthusiasm that ensued in the wake of the initial military successes, many supporters failed to appreciate the tragic irony of Bush’s May 2003 “Mission Accomplished” speech. With a flourish, President Bush arrived aboard the USS Abraham Lincoln in a full flight suit and then, appearing in a more traditional suit and tie, proudly gave Americans a thumbs-up. In the coming years, another photograph of a U.S. soldier, Lynndie England, giving a thumbs-up of her own next to naked Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib prison, would embarrass Americans and darken a popular mood already spiraling downward as the war dragged on.

The war was a diplomatic nightmare, effectively squandering post-9/11 international sympathy and support. A far more deleterious effect of the Iraq invasion was that it distracted American resources from Afghanistan. It did not occur to American leaders or to most of the American public that diverting between 125,000 and 158,000 American troops to Iraq would seriously degrade the security-building effort in the highly porous, decentralized country of Afghanistan.

It did not occur to a majority of congressmen, either. Congress had supported the President because its members failed to ask the difficult questions, such as: What is the imminent threat? Even if Iraq had weapons of mass destruction, how does that make it any different from Iran, Syria, or North Korea? How would a “second front” in the Global War on Terror affect the primary campaign against the group directly responsible for the 9/11 attacks?

Today, we are still groping for ways to provide security to the Afghan people after the Taliban resurgence, which took place precisely during the “Surge” campaign in Iraq, when U.S. troop levels were at their highest.

— All photos via WIkimedia Commons. Photographers in order: Kevin C. Quihuis Jr., Paul Morse, Scott Reed