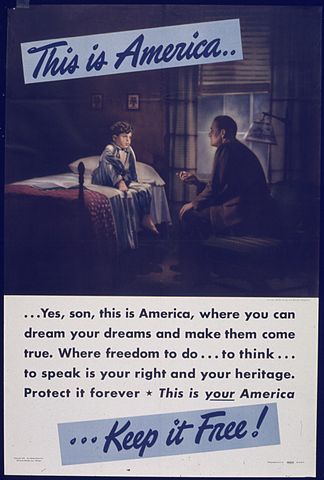

The American Dream. Even if people disagree over how to define it—freedom, economic prosperity, a fresh start—that phrase resonates powerfully in the American imagination. It has proven so powerful, in fact, that several years ago Chinese leader Xi Jinping began promoting what he called “The Chinese Dream.” In recent years, however, numbers of Americans have come to believe that The American Dream is dead, dying, or beyond reach. This month historian Paul Croce asks us to re-examine The American Dream and to take this opportunity not to mourn but to redefine it.

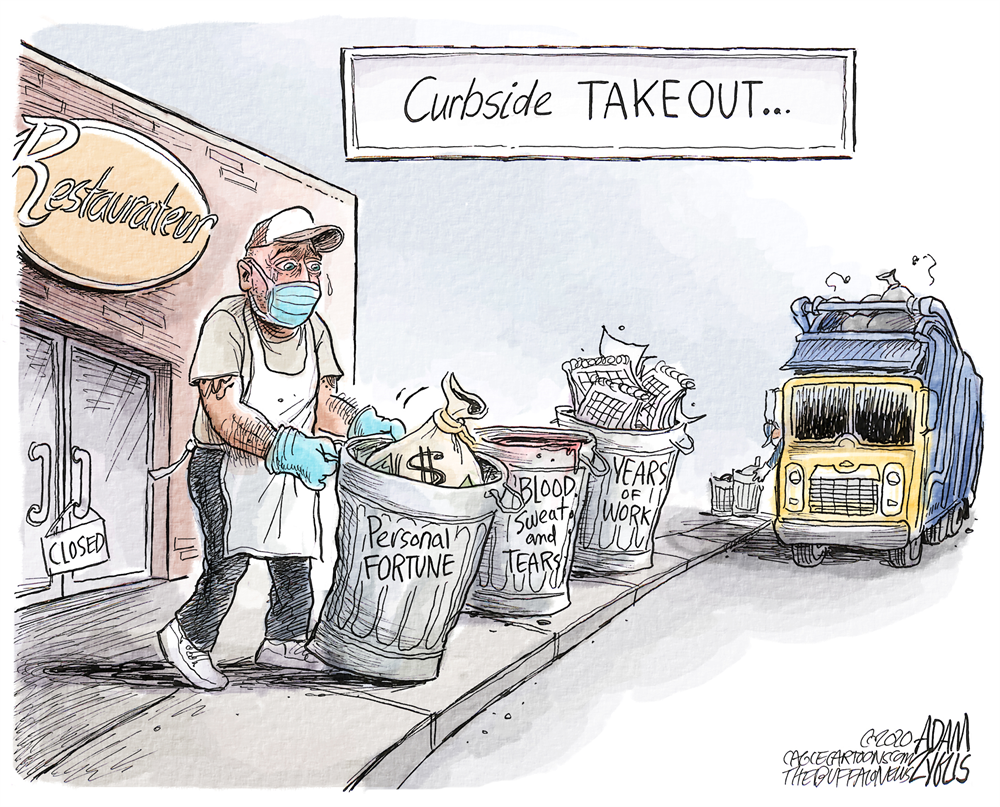

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought widespread changes to the United States and around the world at record speed, from tragic illnesses and deaths to the quirkiness of social distancing and binge-watching online shows.

After years of low unemployment, the initial economic fallout from the virus increased jobless claims in the United States by 3,000% in about a month. Now many American workers and their families cannot reap the fruits of the American Dream.

In fact, cracks in the sterling promises of the American Dream had already been showing up in recent history. Millennials have come of age hearing they are the first generation in American history who will not do as well as their parents.

That equation of the American Dream with wealth, however, misses a deeper sense of what the phrase has meant. It has always been about more than just acquisition of material goods.

Enter the COVID pandemic, which provides us an opportunity to rethink the American Dream and to reclaim the depths of democratic opportunities embedded in it.

The American Dream in American History

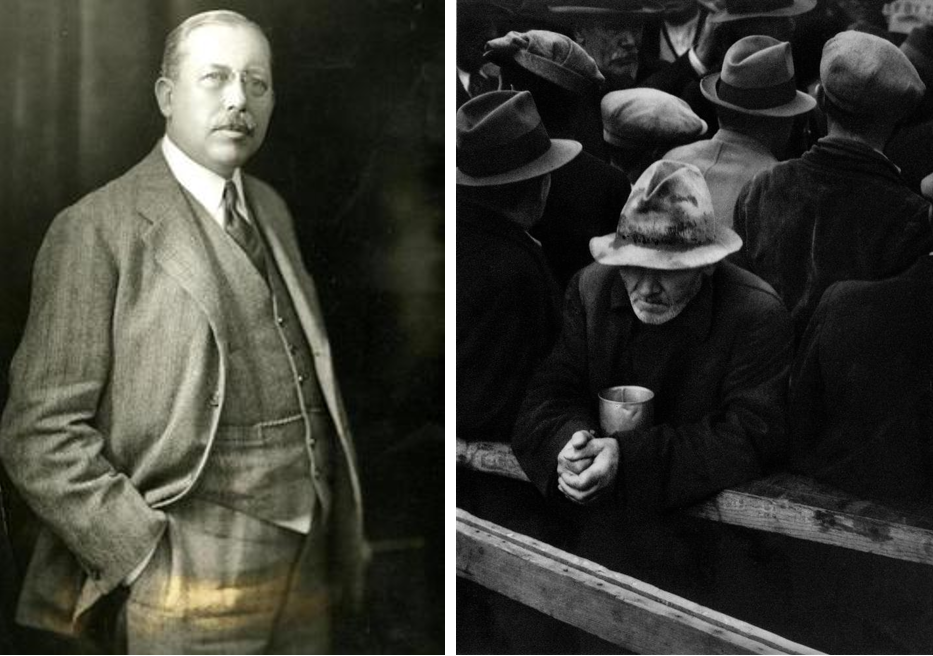

The phrase itself was coined in 1931 by historian James Truslow Adams. Adams expressed confidence, even at the outset of the Great Depression, that the traditional American social dynamics for improving one’s station in life applied to “any and every class.”

Historian James Truslow Adams who coined the term "The American Dream" (left). Requiem for the American Dream: Unemployed men at the White Angel Breadline in San Francisco, California 1933 (right).

Adams’ compelling phrase summarized his portrait of America. He believed that in this land, without the confining impediments of traditional hierarchies, the poor could rise in station based on their own abilities and hard work.

Adams did not acknowledge that these opportunities mostly went to white Protestants, with the hard work and the losses of non-whites and non-Protestants contributing to the opportunities of the privileged. Displaced Natives and enslaved African Americans lived with the cruelest opposite of the American Dream. Their abilities brought sneers and their hard work rarely won them rewards.

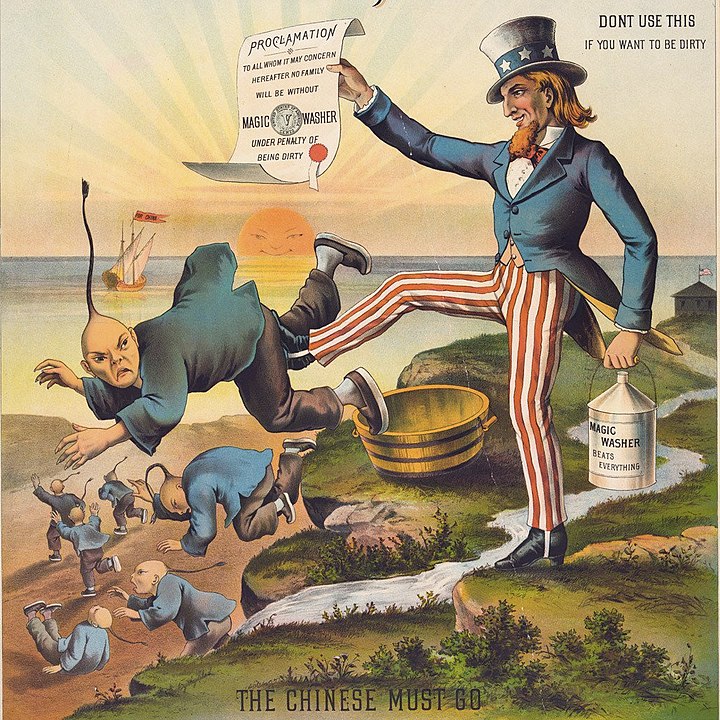

The American Dream has sometimes been supported by withholding opportunities from some people, by immigration restriction or prejudice, to ensure fulfillment of the dream only for the privileged. In 1964 Malcolm X told a crowd: “I don’t see any American Dream; I see an American nightmare.”

That biting commentary shows how deeply the phrase had rooted in the American imagination, which Malcolm targeted for critique. It had become a popular way to describe social mobility, and it has implied confidence that social contexts here could be readily overcome, abilities and efforts were readily rewarded, and problems were only exceptions.

In the United States, dreams would be self-made. And because American society has presented few material or cultural checks on ambition, those dreams could sometimes soar to enormous heights, even without any connection to hard work. One celebrity quoted by James Fallows brashly stated that “being paid more than you’re worth is the American Dream.”

Virus, First Contact

COVID and its economic fallout operated by different principles. Even workers not subject to prejudice, playing by the rules of the American Dream, are finding their ambitions less and less attainable.

With attention first focused on the spread of the disease, a tacit expectation also spread that this was just a peculiar exception to normal times. But as Frank Snowden suggests, this virus may linger and strike in waves as did the 1918 Spanish Flu and the even more deadly medieval Black Death. These diseases, including our current plague, are, after all, only natural—in part.

Environmentalists call recent times the Anthropocene Era, when the human species has wrought enormous impacts on planet earth with climate change and loss of species. But these changes have been accompanied by remarkable cultural and social achievements.

We do live in the Anthropocene, but these times are also a smaller chapter of what could be called the Microcene, a much longer era of earth dominance by microscopic viruses and bacteria. Compared to the successes of the human primate, these creatures are more adaptable, and as William McNeill recounts, they have significant control over human history.

And human development has actually enhanced the strength of viruses and unhealthy bacteria, effectively creating a veritable Microcene Dream for microbes with limited opportunities.

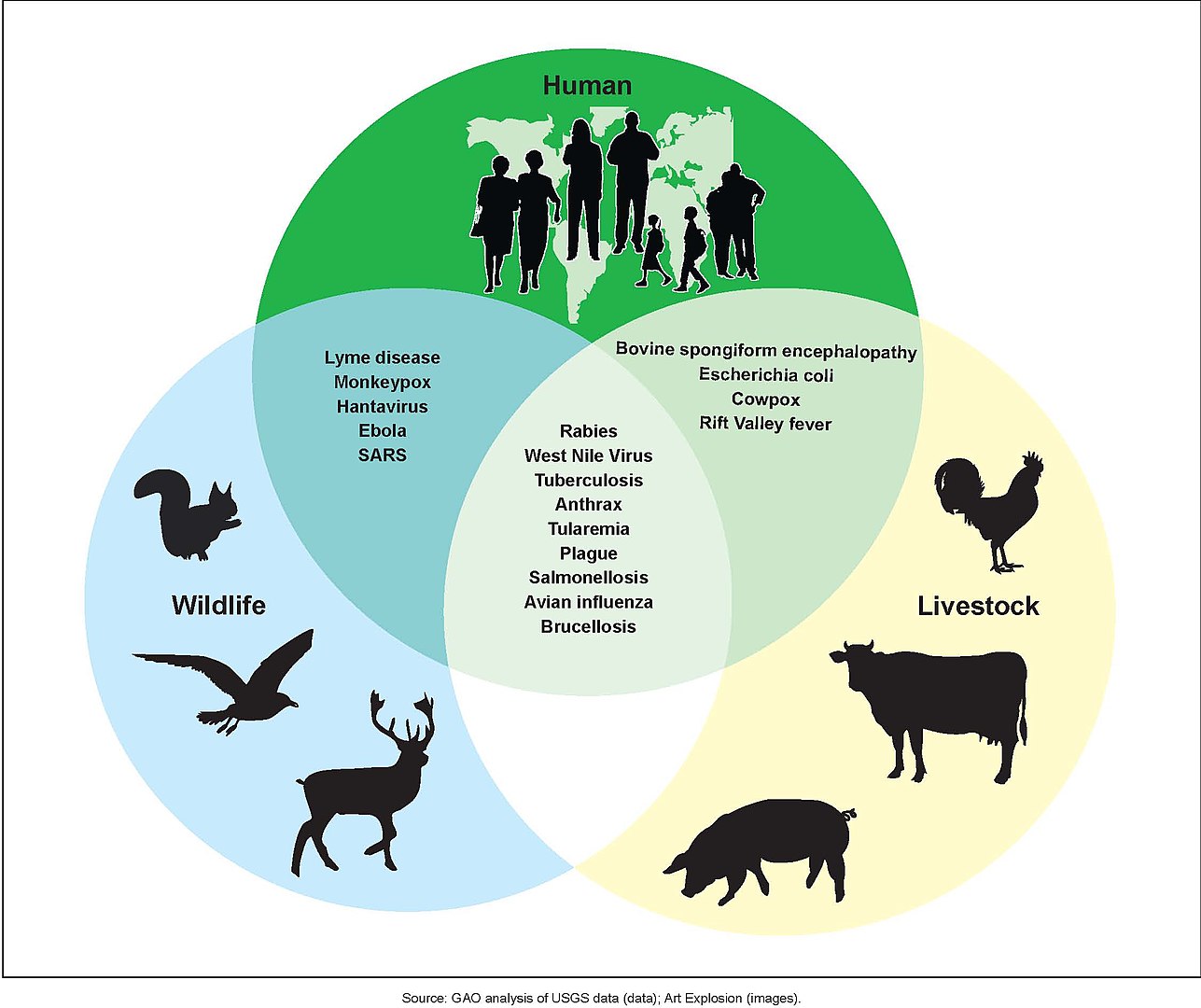

Countless microbes had long remained confined to local settings, but as human habitations have spread, greater contact with wildlife has provided these pathogens with opportunities to migrate out of their old locales. The resulting increased zoonoses, diseases transmittable from animals to humans, make full use of modern human practices.

Examples of Zoonotic diseases and their affected populations.

Globalization provides highways of transmission, and cities, crowded markets, and refugee camps increase potentials for contagion. The diseases are natural, even as human practices amplify their spread and virulence, providing what Ted Steinberg calls the “unnatural” components of natural disasters.

Vulnerabilities Exposed

This pandemic, Farhad Manjoo points out, has alerted Americans that “our society might be far more brittle than we had once imagined.”

Other colossal problems lurk, ranging from skyrocketing healthcare costs, eroding infrastructure, nuclear war, and terrorist strikes to rising sea levels, decimation of fisheries, reduced arable land, toxins leaching into waterways, and other human-made and natural disasters.

Any one of these could disrupt the American Dream even more deeply. The strangest aspect of these strange times may be that it has taken so long for one of these massive disruptions to erupt on a national scale.

The grim possibilities highlight that the American Dream and its success stories have been skating on assumptions of a generally healthy, undisrupted, and peaceful society. Americans have faced disasters before: epidemics, hurricanes, earthquakes, depressions, and wars. Most of them have been localized, temporary, managed, or offshore, as with almost every American war.

This history has encouraged a sense that such problems are exceptions to the regular smooth operations of society, not factors to consider seriously compared with the abundance of opportunities. Even the tens of millions of deaths worldwide from the 1918-19 Spanish Flu, a largely forgotten pandemic, did not dent this powerful American self-understanding.

For hundreds of years, looking beyond disasters has been the norm for American majorities. Americans weathered the setbacks while the dream endured because better opportunities always seemed just around the next corner.

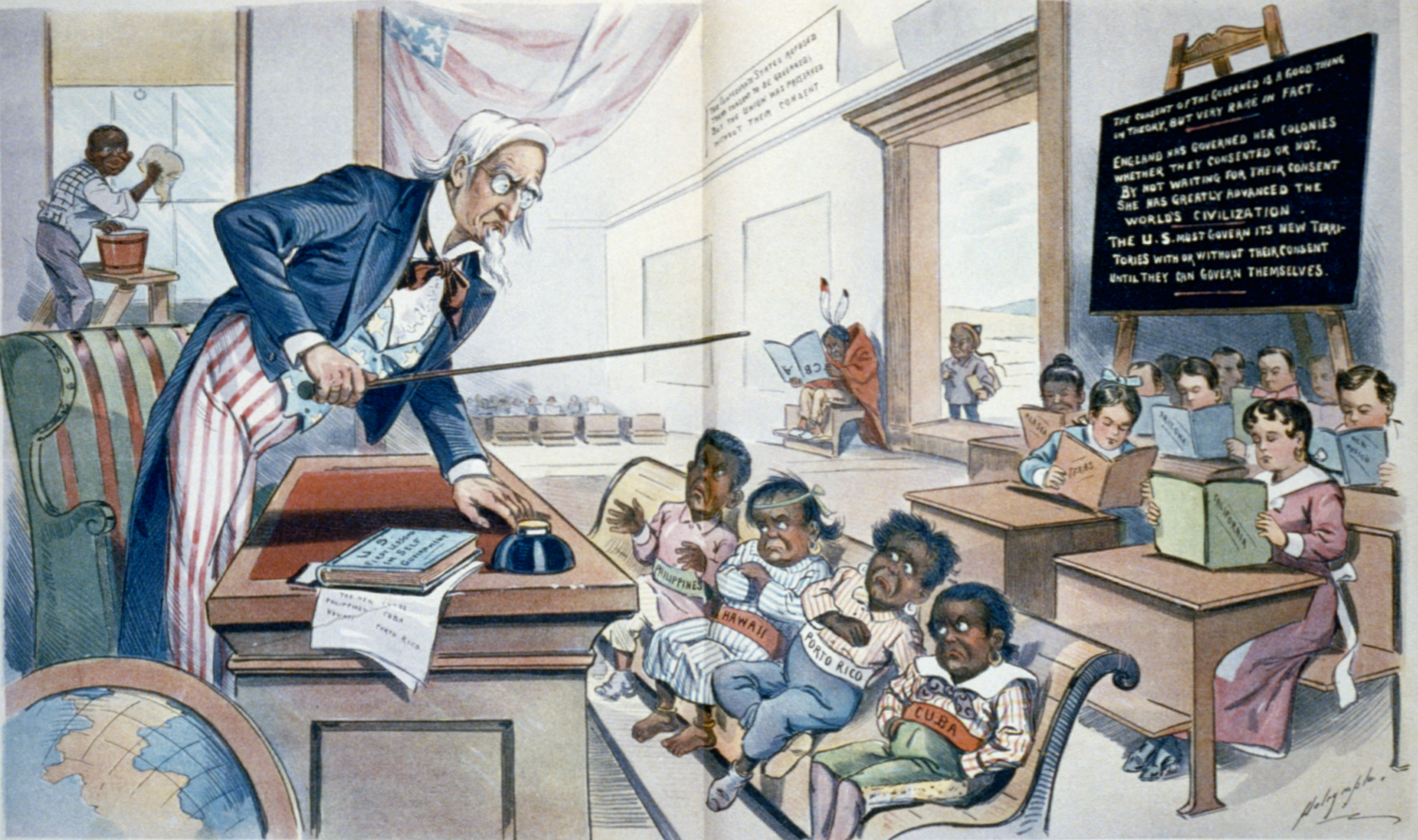

Historically, expansion has been a prime way to overcome limits on opportunities.

Caricature of American expansionism and racism showing Uncle Sam lecturing four children labelled Philippines, Hawaii, Puerto Rico and Cuba in front of children holding books labelled with various U.S. states. In the background are a Native American child holding a book upside down, a Chinese boy at the door, and an African American boy cleaning a window. Originally published in the January 25, 1899 issue of Puck magazine.

Initially, that expansion was geographic with growth across North America to Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and more territories. The expansion has also been economic, with growth in markets enabling industrious citizens to rise in station. And expanding rights have allowed more nonwhite citizens their own paths of opportunity.

Throughout, the key to the American Dream has been growth, with each generation expecting more of it. Fixation on growth has been hard-wired into our national policies and personal expectations.

Presidential administrations are measured by their ability to generate economic growth while bigger houses and larger flat screens measure our personal success. Mainstream economists can’t conceive of economies that don’t grow. No wonder Americans rarely question this design feature of our national self-perception.

The dream of personal advancement has inhibited the response to the COVID-19 outbreak, which calls for Americans to rise to public challenges.

Hospitals, pushed to produce profits, find themselves without enough equipment as front-line workers sacrifice for the common good. Businesses focused on efficiency and profits are hard-pressed to adapt to urgent changes. The entire system built to achieve growth is short on resilience.

Bipartisan Endorsements of the American Dream

The American Dream with its assumptions of constant growth has enabled the United States to be simultaneously conservative and liberal.

There is conservatism in the incentives for enterprising economic ventures, with impulses for low taxes and reduced regulation; there is liberalism in legal support of rights for more citizens, often expressed with material uplift. These views, with accompanying ideological debates over a host of domestic and foreign policy issues, are generally assumed to exist in sharp contrast.

In fact, polarization is the dominant political storyline of our time. Yet these flares of fighting surge around a deep consensus about the American Dream.

Each ideological position aims to defeat the other side. But unless the nation can find ways to revise dreams about material abundance with support of other rewarding parts of the American dream, proponents of each ideological position will suffer. So too will the whole United States, with conservatives seeking to squeeze more riches from our resources and liberals gamely striving to ensure that more can share in those riches.

Rarely have we had serious discussions about the limits to material gains or, more generously, about how that growth might be shared more equitably. Bipartisan criticism accompanies any portrait of a society that includes less striving for more and more. Conservatives taunt that without growth, enterprisers will be punished. Meanwhile, liberals rely on growth to bring more citizens into the prosperity tent. Both outlooks assume life without major disasters.

American education has served as a great bipartisan equalizer. However, as Victor Tan Chen points out about recent attempts by wealthy and celebrity parents to gain advantages for their children in college admission, “opportunities to acquire talents and skills [have] become lopsided.”

Recent economic and cultural trends have actually shaken the promises of the American Dream.

Looking Squarely at the American Dream, Side Effects and All

The American Dream, with its assumptions about resources readily available for human enterprises, has shown little reckoning with the environmental impact of those human dreams.

In fact, this traditional way of using resources displays what American philosopher and psychologist William James called a “wishing-cap” approach to life. He referred to the “apps” available in the early 20th century: “We want water and we turn a faucet. We want a kodak-picture and we press a button. We want information and we telephone.”

Fast forward to fancier apps, but the point is the same: rather than having to think about the sources or implications of our wishes, “we hardly need to do more than the wishing—the world is rationally organized to do the rest.”

The system is well suited to addressing the material parts of the American Dream but does not sustain the environmental services that contribute to material prosperity.

Living with comforts, enjoyment, and creativity does require resources, but these do not need to be on very large scales. Thomas Jefferson endorsed the virtue of “a middling level of development,” with freedom from the pain of want and from the burdens of managing extensive holdings.

While possession of some material goods supports happy and fulfilling lives, acquisition of many more does not make us happier or enhance our wellbeing. In fact, acquisitiveness even tends to undercut these goals.

Studies in the field of Positive Psychology point to the good work and enjoyment from living with sufficient but not excessive resources. This degree of abundance actually addresses the desires of most citizens and their families, especially if other parts of their lives are fulfilling.

Beyond an American Dream of More Stuff

For the next chapter of human history, the challenge will be maintaining the continued flow of the American Dream’s achievements with fewer of its problems. How do we mitigate the constant pressure for more material things, which has been tempting fate by inviting material disasters, but continue to enable personal development, healthier social relations, and creativity?

The system of constant economic growth has been wonderful for many people, even as it also has produced enormous side effects, which do not gain as much attention as the wonders of the system.

City of Portland Landfill, 1973. Mass consumerism has produced mass waste.

James recognized the temptation to pay attention only to the most familiar, “all we [already] know,” where “we are absolutely at home,” even though this way of thinking overlooks the robust whole “phenomenon” of experience.

That’s a fancy way of urging recognition of both the outstanding achievements that result from the familiar tradition of constant growth and its less acknowledged but often dreadful unintended effects.

Imagining steps beyond the routines of constant growth can be difficult because we swim in its assumptions. As Tim Jackson recognizes, people who choose alternatives “find themselves at odds within their social world.”

Life with the production and consumption of constant growth is the central habit of modern times, and as James points out, once set, a habit serves as an “invisible law, as strong as gravitation,” enabling efficiency and comfort—as long as those routines work. But our habits are not our destiny. Habits are not even permanent, he adds, because of humanity’s “extraordinary degree of plasticity.”

Most of the side effects of the American Dream amplified by constant growth are problems of scale. Each individual act of pollution, while not good, is not world destroying. But on mass scales, they can become overwhelming disasters, much like viruses expanding beyond local settings.

Each bottle not recycled, each errand run by car rather than on foot, each cigarette butt tossed on the ground has little environmental impact by itself. But when ignored by individuals and by systems with no incentives for healthier actions, the collective mass creates massive destruction.

Yet small changes by individuals and structures can add up. As James says, there is “legitimacy [in] some.” That is true many times over in mass culture. Plus, taking one step at a time not only avoids some of the difficulties of change, but it also can recruit the hesitant who feel overwhelmed by the enormity of the problems.

The American Dream 2.0

Will America, in words often attributed to Winston Churchill, “do the right thing, after exhausting all the alternatives”?

The sooner more can rally to finding riches beyond the material, the sooner we can figure out the healthier paths, with less squeezing for material gain. That will turn our attention to the less-material rewards of the American Dream, with its democratic hopes for more people to gain uplift in ways not always connected to possessions.

When Americans work hard, they generally expect rewards to come from their initiative, and they generally pay little attention to the side effects of their gains. The current health disaster presents an opportunity to continue dreaming, with less destruction and with less vulnerability to current or future crises.

Center for the Advancement of a Steady-State Economy, http://steadystate.org/, http://steadystate.org/

Victor Tan Chen, “The Spiritual Crisis of the Modern Economy,” The Atlantic, December 21, 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/

Satyajit Das, The Age of Stagnation: Why Perpetual Growth is Unattainable and the Global Economy is in Peril (Prometheus Books, 2016)

Sarah Churchwell, Behold, America: A History of America First and the American Dream (Bloomsbury, 2019)

Jim Cullen, The American Dream: A Short History of an Idea that Shaped a Nation (Oxford, 2003)

Anand Giridharadas, Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World (Alfred A. Knopf, 2018)

Robert Gordon, The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The US Standard of Living Since the Civil War (Princeton, 2016)

Tim Lee, “27 Charts that will change the way you think about the economy,” October 10, 2016, http://www.vox.com/new-money/

George Packer, “Underlying Conditions,” Atlantic Monthly, June 2020, writing, PackerFailedStateAtMoJUN20; https://www.theatlantic.com/

Robert Zubrin, Merchants of Despair: Radical Environmentalists, Criminal Pseudo-Scientists, and the Fatal Cult of Antihumanism (New York: Encounter Books, 2013)