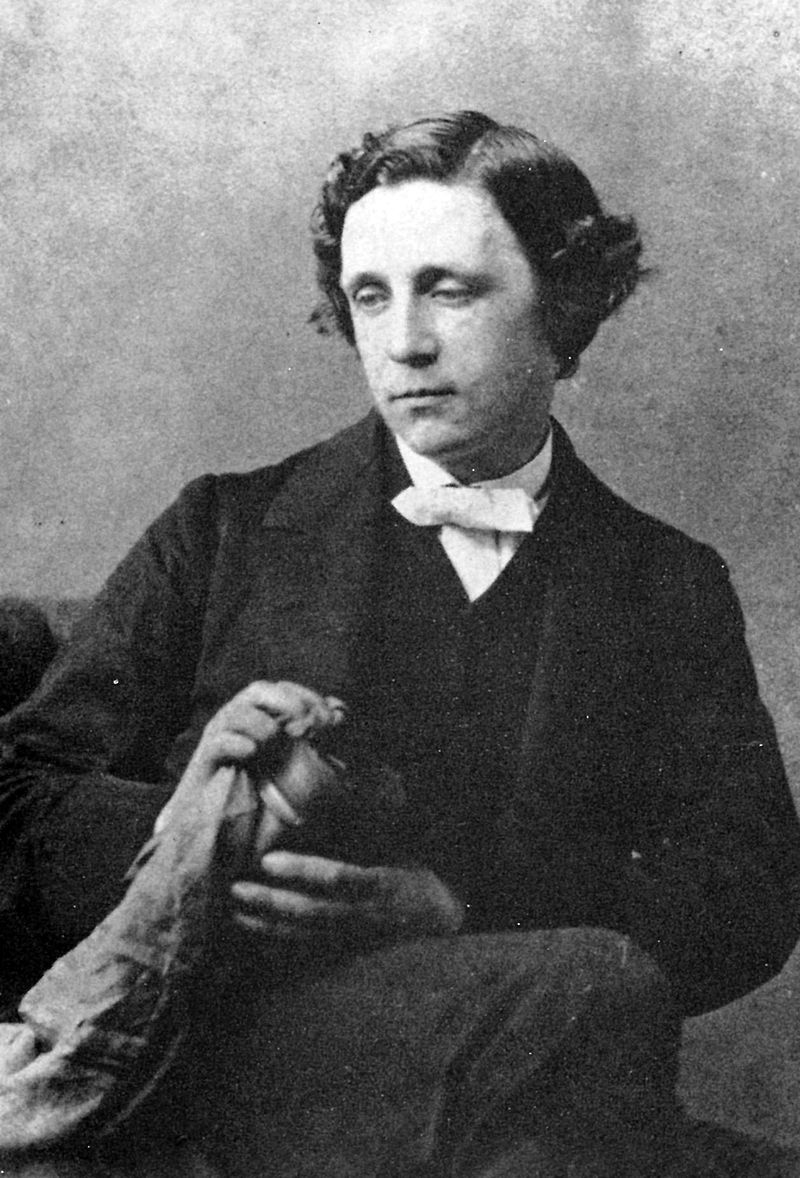

Alice in Wonderland, the little girl created by Oxford mathematician and logician Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (Lewis Carroll), celebrates her 150th birthday this year. While her pinafore and his frockcoat and long wavy hair, old fashioned even for their time, catch our eye and distance them far from us on the other side of the tumultuous 20th century, our ear tells us a different story.

|  |

People of all ages are eager for this story—they have kept Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in print in tens of thousands of editions; they have translated it into over 170 languages in over 7000 editions; they have taken the story and made it their own and sent it back out into the world in plays, movies, paintings, ballets, and every possible art form. They have expressed it within their personal lives in collections, crafts, décor, tattoos, and passionate tellings and sharings

This story of Alice in Wonderland is a modern story, modern in every era, fresh and contemporary, startling and biting.

Without specifically lampooning anything, Carroll sketches in broad strokes life itself—the journey we all take through a confusing landscape with a dim idea of a conventional goal. As we encounter one authority figure after another, we try to apply what we have been taught about how to speak and act, and how to negotiate with them while attempting to fulfill our own purposes as well.

|

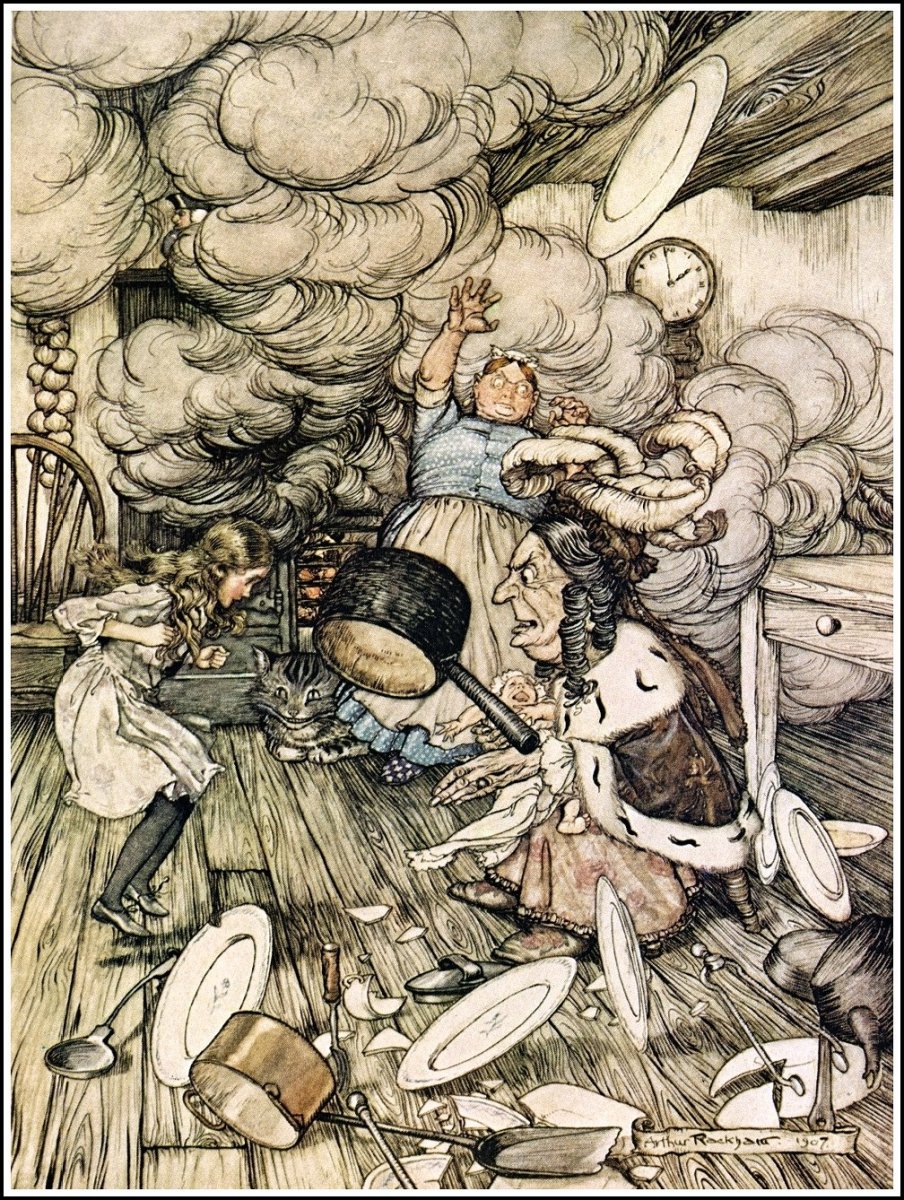

In most stories for children leading up to 1865, the point of such a journey for a child character was to demonstrate to the child-reader what acceptable speech and behavior were, and what the painful and even fatal consequences were of disobedience. Carroll, however, was on the side of the child, an adult ally who told a different story. The authority figures Alice meets are ridiculous—they speak in riddles, they engage in purposeless activities, they are dismissive of Alice, and they are arbitrary and even violent. Putting a child’s view of the adult world at the center of the story was one of Carroll’s strokes of genius.

Alice attempts to deal with the adults with politeness and moderation, but increasingly realizes that she is not obliged to take them at their own estimation of themselves. Finally, she rejects the claim of crown and court to have control over her, in one spectacular act of truth-telling: “You’re nothing but a pack of cards.” Naming this sham hegemony for what it is brings her dream to an end and sets her free to live an authentic life.

|  |

Alice was modern for the Victorians, modern and relevant for James Joyce, modern and transformative for John Lennon, and influential on so many people over the years. And the book remains vital for us today because we always need to be reminded not to give our power away to the man behind the curtain.

Carroll reminds us of these truths in a voice we can hear, the voice of the storyteller. Stories have traction in our imagination. They require us to enter into them, and the subversive narrative tone of Alice, dry and ironic, creates complicity with the reader.

Once drawn into collusion by the subtle voice of nonsense, we willingly experience Wonderland, recognizing truths out of the corners of our eye, and, along with Alice, we are transformed.