On the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, the Armistice went into effect, silencing the guns of the Western Front and ending the First World War. Or so the story goes.

In January 1918, after forty-one months of combat, Allied troops were ready for a ceasefire, but they certainly didn’t expect that it would be forthcoming. The Russian Revolution, French mutinies, Italy’s defeat at Caporetto, and the exhaustion of British forces after Passchendaele—1917 had been a bad year for the Allies. The United States had entered the conflict in April but the initial impact was negligible—the Army was comprised of just 120,000 men.

After the exhaustion of British forces at Passchendaele (left) and the Russian Revolution (right), 1917 had been a bad year for the Allies.

By mid-1918, however, the tally of U.S. troops on European soil swelled to half a million, the British naval blockade had eroded German home-front support for the conflict, and the failure of the Spring Offensive caused German soldiers’ morale to plummet.

The impact was devastating. On August 8, 1918, 17,000 German soldiers surrendered to the Allies following a British offensive on the Somme and between summer and fall, the German army saw the attrition of 750,000 to one million men. In many cases, they simply went on leave and never returned.

On August 8, 1918, 17,000 German soldiers surrendered to the Allies.

The end was in sight. On September 30, 1918, German ally Bulgaria was forced to sign an armistice in Salonika. In the following weeks, strikes spread throughout German factories and, on November 9, Kaiser Wilhelm II went into exile in Holland. The new German government sued for peace.

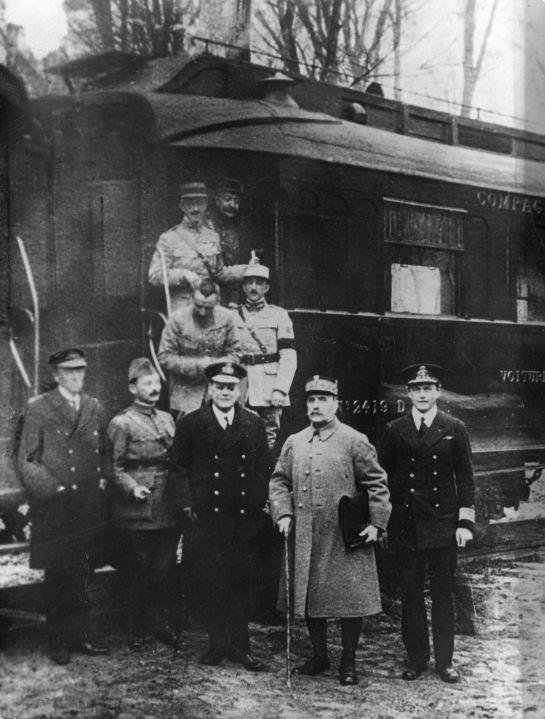

At five in the morning on November 11, 1918, the German delegation met Allied Commander Ferdinand Foch, and signed the Armistice in his railway car, parked in the French forest of Compiègne. The Armistice, which took effect six hours later, called for a cessation of hostilities, Germany’s immediate withdrawal from invaded countries, the surrender of their arms, the repatriation of all Allied prisoners of war, and the creation of a neutral zone in the Rhineland.

At five in the morning on November 11, 1918, the German delegation met Allied Commander Ferdinand Foch, and signed the Armistice in his railway car, parked in the French forest of Compiègne.

Peace negotiations continued until June 28, 1919, when the formal treaty was signed in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles.

So when did the First World War end? November 11, 1918? June 28, 1919? Or was it later?

By the end of World War I, both the Russian Romanov and the German Hohenzollern dynasties had collapsed (Romanov Empire Historical Society).

The French concept of sortie de guerre—or the transition from war to peace—asks us to re-examine the traditional chronology of warfare, to consider aspects of the war such as the continuation of violence, demobilization, veteran rehabilitation, and mourning as critical components of the conflict itself.

While the fusillade may have stopped on the Western Front in November 1918, fighting continued. In Germany, 400,000 veterans joined the freikorps, military units who fought against domestic revolutionaries in 1919-1920. Civil war continued in Russia and Ireland. Border conflicts between Russia and Poland and between Greece and Turkey extended into the early 1920s.

In Germany, 400,000 veterans joined the freikorps, military units who fought against domestic revolutionaries in 1919-1920.

The conflicts, moreover, created a vast refugee crisis. In the autumn of 1920, Germany absorbed half a million refugees from Poland and the Baltic region. The scale of the war was unprecedented and so too were its consequences.

Among the Allied and Central Powers, more than 65 million men and women were mobilized in the war. Following the Second World War, combatant troops would be deployed for finite tours of duty, but in the early-twentieth century, troops typically stayed in the war for its duration. This meant that demobilization was a massive and prolonged undertaking.

German POWs only began to be released from Allied camps at the end of 1919.

For example, French troops who had begun compulsory military service in 1912 duly entered the war in 1914 and remained under military authority until 1919. It took from November 1918 until spring 1920 for France to demobilize its more than five million active troops. Beyond that, 25,000-40,000 French colonial soldiers stayed on, occupying the German Rhineland.

The repatriation of prisoners of war was similarly protracted—German POWs only began to be released from Allied camps at the end of 1919.

More than eight million men were permanently disabled after World War I, and the road to recovery was a long one.

The millions of men who left the war prematurely continued the battle by other means. More than 20 million men were wounded in the First World War; many multiple times. In the majority of cases, men were treated in field hospitals and returned to the lines. However, more than eight million men were permanently disabled and the road to recovery was a long one.

Centennial Ceremony at Thiepval, France, July 2016 (Photo courtesy of author).

The belligerent powers were largely unprepared to deal with the needs presented by the war disabled. They hastened, throughout the conflict—and with varying degrees of success—to set up centers for physical therapy, workshops for the manufacture and fitting of new prosthetic limbs, and schools for the vocational re-education of soldiers whose wounds prevented them from returning to their previous occupations.

To give a sense of scope: from the beginning of the war until December 31, 1918, Great Britain alone pensioned 520,989 men for disability; 28,661 limbless men passed through limb fitting hospitals; and 20,828 of them underwent vocational re-training. There would be more to come.

Poppy wreaths to honor the fallen of World War I, Green Park, London, March 2018 (Photo courtesy of author).

Critically, national security during the conflict and in the postwar period meant that the war disabled had to return to work. It was their duty to work, as it had been their duty to fight.

In his “Message to Every Disabled Soldier,” United States Army Surgeon General William C. Gorgas wrote that: “No matter what has befallen you, you are still a soldier. Although you have returned from the front you have to fight new foes more worthy of your steel than the Germans: discouragement, loss of ambition, readiness to accept the easiest way, reluctance to play your part in the peace world. We know you will conquer these enemies. Your country needs you yet to fight the battles of peace.”

“Those who died piously for the country: parishioners dead on the field of honor, 1914”: a mosaic on a church in Montmartre, Paris featuring the names of the dead (Photo courtesy of author).

While disability prolonged a man’s battle, death cut it short. Nevertheless, the process of mourning the dead—practiced by friends, family, and brothers-in-arms—continued the war indefinitely.

Death tolls were extraordinary. Around 10 million combatants were killed, including 2 million Germans, 1.8 million Russians and 1.3 million Frenchmen. Thirty-seven percent of Serbian combatants perished, 26% of Romanians, and 23% of Bulgarians. The epidemic of Spanish Flu that raged from 1918-1919 killed as many as 50 million soldiers and civilians.

Cardboard poppies staked into the ground at the Thiepval memorial, Thiepval, France, July 2016 (Photo courtesy of author).

Put plainly, everyone had been touched by death. Oftentimes, there was no grave to visit and no body upon which to perform funereal rights that might bring loved ones peace and closure. Thirty percent of bodies were completely destroyed by artillery and could not be identified and the repatriation of bodies buried on the battlefield was largely prohibited either by law or practicality.

Death on a massive scale and an inability to perform traditional rituals led to new practices of mourning—particularly in Europe where large portions of the population had been mobilized and casualties were staggering.

Mourning became less private and more collective. War tourism as pilgrimage became popular and memorials were established in villages and towns to commemorate the dead; some grand, some modest. In 1920, a Tomb of the Unknown Soldier was erected with solemn pomp and circumstance in Paris and in London. Similar memorials followed in Washington D.C. and Brussels in 1921.

Wooden crosses at the Thiepval memorial, Thiepval, France, July 2016 (Photo courtesy of author).

Nations mourned together. Importantly, they still do.

This November 11, 2018, one hundred years after the armistice, people will gather in capital cities, in town squares, at cemeteries and memorial sites throughout the world—for many an annual ritual—to commemorate the war and mourn the dead. They will offer poppy wreaths, wooden crosses, and words of remembrance to the fallen.

Indisputably, the war lives on.

Commemoration of World War I, Notre Dame, Paris, November 2017 (Photo courtesy of author).