The organization created to end war, the League of Nations, began its functional existence with an empty chair crisis.

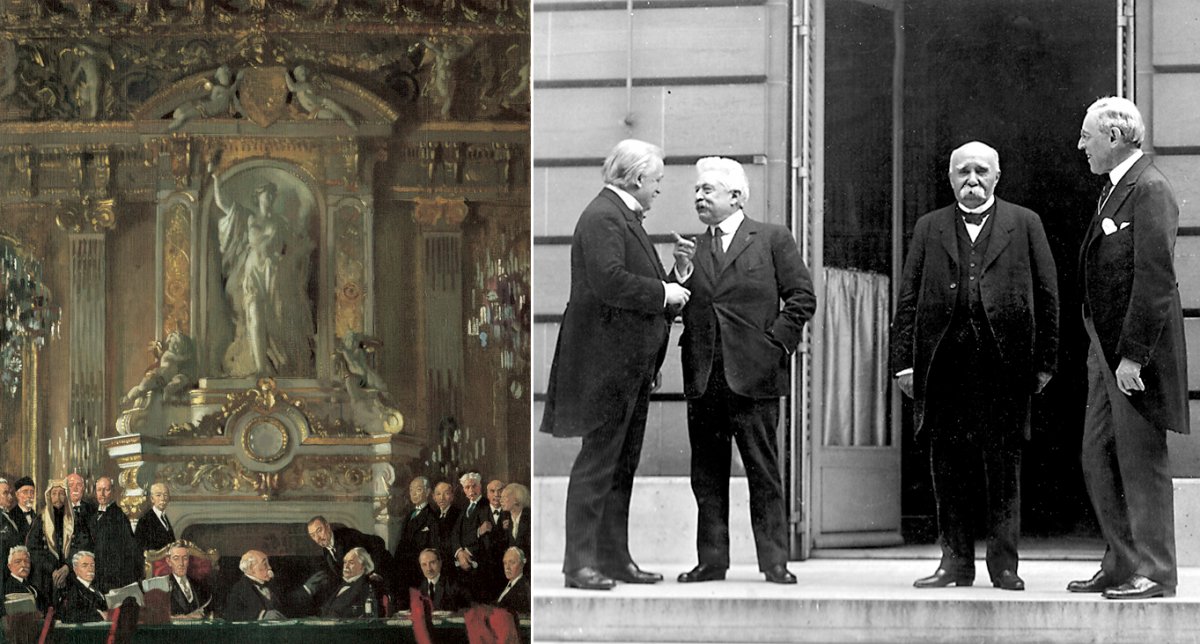

The League’s top political body, the Council (on which today’s United Nations Security Council is modelled), met formally for the first time on January 16, 1920. The leaders of the victorious Allies of the First World War, plus heads of state and ministers from over forty countries across the globe, had gathered for the occasion in the vast, baroque Clock Room of the Quai d’Orsay, the Second Empire-style headquarters of the French Foreign Ministry in Paris.

"A Peace Conference at the Quai d'Orsay," by William Orpen (1919) (left); the "Big Four" at the WWI Paris peace conference, May 27, 1919: British Prime Minister David Lloyd George; Italian Premier Vittorio Orlando; French Premier Georges Clemenceau; U.S. President Woodrow Wilson (right).

The meeting was marked by a most conspicuous absence.

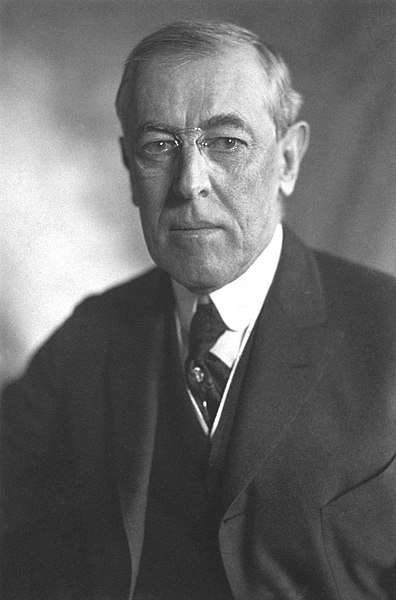

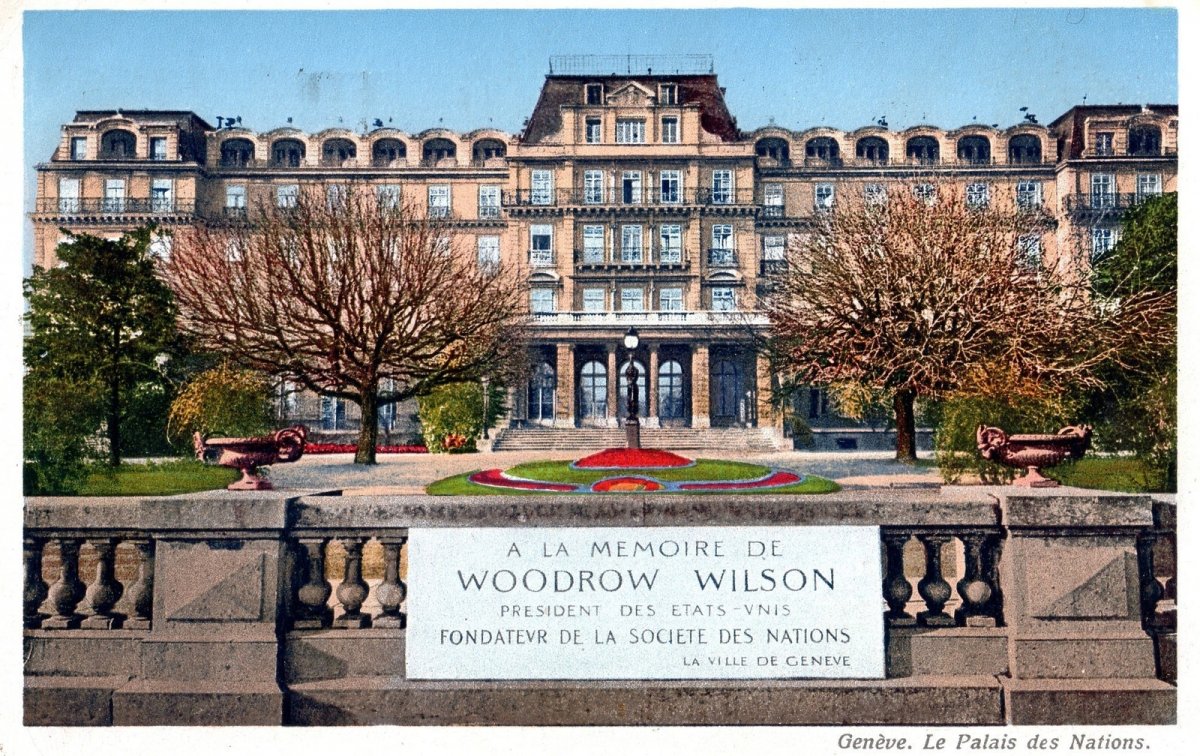

One seat at the main table, where the Council’s permanent members sat underneath a statue symbolizing France, had been left empty for Woodrow Wilson. The President of the United States had done more than any to promote the League’s cause. His wartime call for “open covenants of peace, openly arrived at” became the standard by which the organization was and is measured.

Wilson could not attend the Council meeting, however, because he was locked in an increasingly bitter struggle with the U.S. Senate in Washington, D.C., over ratification of the Treaty of Versailles, which ended the state of war between the Allies and Germany.

Crowds celebrate the announcement of the end of World War I in Philadelphia, 11 November 1918.

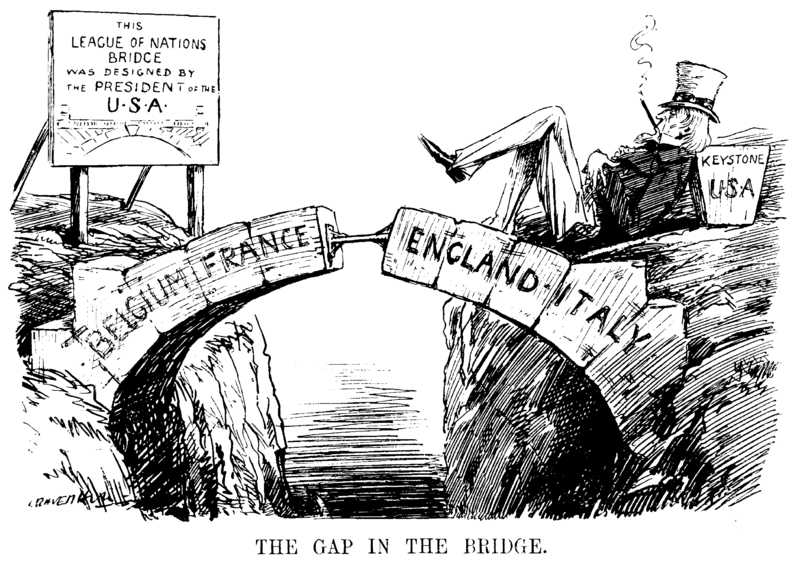

Only two months before, on November 19, 1919, the upper chamber of Congress had refused to back the Treaty Wilson had painstakingly negotiated over the first six months of that year. Since Part I of the Treaty was the Covenant of the League, this also put in jeopardy U.S. membership of the organization Wilson had done most to promote.

Yet the League and Versailles got a second chance. There was too much at stake to leave it to a single vote, as the Council, with its empty chair, recognized. Senate leaders, too, were loath to go down the road of a separate peace with Germany, which a rejection of Versailles would necessitate.

Following a bipartisan conference in January 1920, the Senate reopened consideration of the Treaty. But when a second resolution of ratification was put to a vote on March 19 (scarcely two months after the Council meeting), it, too, failed to gain a two-thirds majority. Versailles became one of only three treaties in history to have been rejected by the Senate not once, but twice.

Thus began the U.S.’s fraught relationship with multilateralism in the twentieth century.

Wilson’s defeat marked the outer limit of U.S. foreign policy for a generation. The way in which the U.S. assumed global leadership after 1945, under his Democratic heirs Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman, was in large part a response to it. Indeed, memory of the “Treaty Fight” continues to shape the debate on America’s place in the world today—but not in the way one might think.

The traditional way in which the Treaty fight was long remembered is as a conflict between Wilsonian internationalists and so-called “isolationists.” According to this narrative, the former wanted deeper American participation in global affairs and international organizations. The latter desired to isolate the U.S. from the power politics of the Old World.

Supposedly, the isolationists represented a deeply rooted national sentiment that went back to George Washington’s 1796 Farewell Address, on which Thomas Jefferson built when he famously warned against “entangling alliances” at his 1801 inauguration.

The two decades after 1919, the story goes, were the high-water mark of isolationism in American history. Not until the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 was its stranglehold on American politics broken. Only afterwards could the internationalists turn the country’s immense power to responsible global leadership and the construction of a liberal international order.

Current debate on U.S. foreign policy is rooted in this version of history. Worries about the future of the liberal international order under the Trump administration are regularly tied to the supposed isolationism of his electorate.

Isolationism, however, is not why the Senate rejected the Treaty of Versailles and the Covenant. Moreover, it is a deeply misleading label for the way the U.S. engaged with the world in the interwar period. Recognizing this has consequences for the way we see America’s place in the world after 1945, even today.

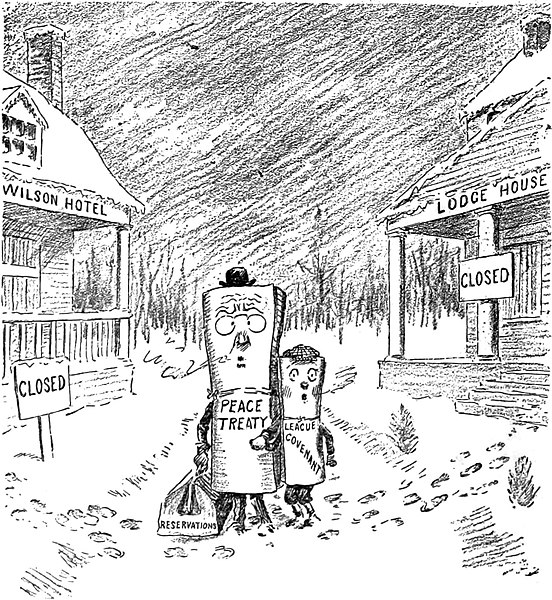

In reality, the Treaty fight was not a two-way contest. Besides the Wilsonian internationalists, who wanted the Treaty and Covenant ratified unchanged, there were those who wanted to add so-called reservations to the treaties: conditions to U.S. acceptance and participation in the League that the other signatories would have to accept.

To make matters more complicated, these “reservationists” came in two flavors: mild and strong. The former included more than a few Democrats; the latter were dominated by leading Republicans like Senate Majority Leader Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts or former President William Howard Taft.

Crucially, the reservationists were not opposed to the treaties, U.S. membership in the League, or a role for America in upholding the postwar order. They simply disagreed with Wilson on the conditions of doing so.

This set them apart from the small but loudly vocal group of “irreconcilable” Senators, led by William Borah (R-ID) and Hiram Johnson (R-CA), who rejected the treaties wholesale. Yet even they were no isolationists. Borah and Johnson were prominent progressives and anti-imperialists, who saw the Treaty and Covenant as violations of the precepts of international law they had always defended.

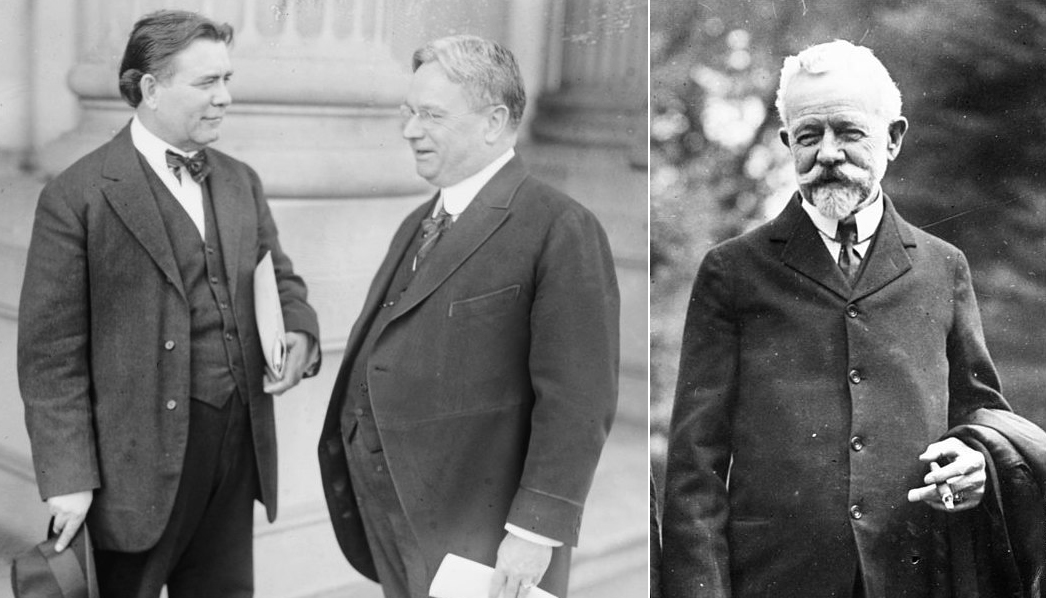

Senators William Borah and Hiram Johnson c. 1921-1922 (left); Senator Henry Cabot Lodge in 1924 (right).

On November 19, 1919, there were actually two votes, rather than one, in the Senate. The first was on a resolution to ratify the Treaty and Covenant unamended. The second included fourteen reservations proposed by Lodge, in close consultation with the Republican caucus. Neither passed.

The final vote, on March 19, 1920, was on Lodge’s reservationist resolution. It failed because Wilson himself, in a letter to the Democratic caucus, threatened to exercise his veto if it were accepted. Half the “Wilsonian” Democrats consequently joined the irreconcilables in voting against. The alliance of Lodge’s Republicans with the remainder of the Democrats was not enough to secure a two-thirds majority. Wilson himself thus bore great responsibility for killing the prospect of U.S. League membership.

While this outcome set the country on the path of unilateralism, the U.S. was hardly isolated from interwar world politics. Under Wilson’s Republican successor Warren G. Harding, it hosted the Washington Naval Conference, the most important arms control conference of the era, and one of the most comprehensive of all time. The Federal Reserve, created under Wilson, collaborated closely with the Bank of England, Banque de France and the Bank of the Netherlands to stabilize the post-war global financial system through massive austerities.

Even in Geneva, the League’s Swiss headquarters, Americans formed one of the larger national contingents. Much of the League’s economic and social work was funded by philanthropies like the Rockefeller Foundation. Rockefeller also funded efforts led by U.S. banker (and future Vice President) Charles G. Dawes, in 1924, to renegotiate the reparations Germany owed the Allies according to Versailles.

It came as little surprise to contemporaries, then, that in 1940, as war engulfed Europe, the League’s socio-economic sections were evacuated to Princeton, New Jersey. There, they played a key if understated role in preparing the way for the United Nations.

However, in order to get the U.N. through Congress, FDR was forced to draw as big a line as possible between it and Wilson’s legacy. Part of his rhetorical strategy was to paint sceptics of the new organization, such as supporters of a postwar return to neutrality or anti-war activists, as misguided “isolationists,” who had helped cause the Second World War by rejecting the League.

We thus owe the story of the isolationist-internationalist struggle to the Roosevelt administration’s campaign for the U.N., not to the Treaty fight.

Though evidently effective, Roosevelt’s move has had a problematic legacy. We still tend to think in terms of “isolationists” versus “internationalists” today. But, then as now, there are very few real isolationists out there.

Both President Donald Trump’s supporters and opponents advocate competing forms of internationalism—free-trading and Christian in the case of Mike Pence, for example; pacific and juridical in the case of the recently founded, Trump-skeptical Quincy Institute. The sooner we recognize this, the sooner a more open, intelligent and productive debate on the U.S.’s place in the world will be possible.

Vice President Mike Pence delivering remarks at a rally in Minnesota, 28 March 2018.