1960, often known as the Year of Africa, marked a turning point of African independence with 17 new countries created that year, 18 the next, and 13 more by the decade’s end. This month, to mark the 60th anniversary, three historians—Katherine Everett, Emily Hardick, and Damarius Johnson—revisit 1960 and its many legacies. Looking at such shared histories as infrastructure development, rumba, and Pan-Africanism, they help us think about Africa in a global context. The promises of that new decade were not all realized, but the Year of Africa set in motion events that shape our world today. –Thomas McDow

Reframing the Year of Africa: Independence as a Process

By Katherine Everett

The year 1960 is known as the “Year of Africa,” when 17 countries across the continent celebrated the joy, excitement, and possibilities of independence. But liberation in Africa was more than this one moment in the global process of decolonization.

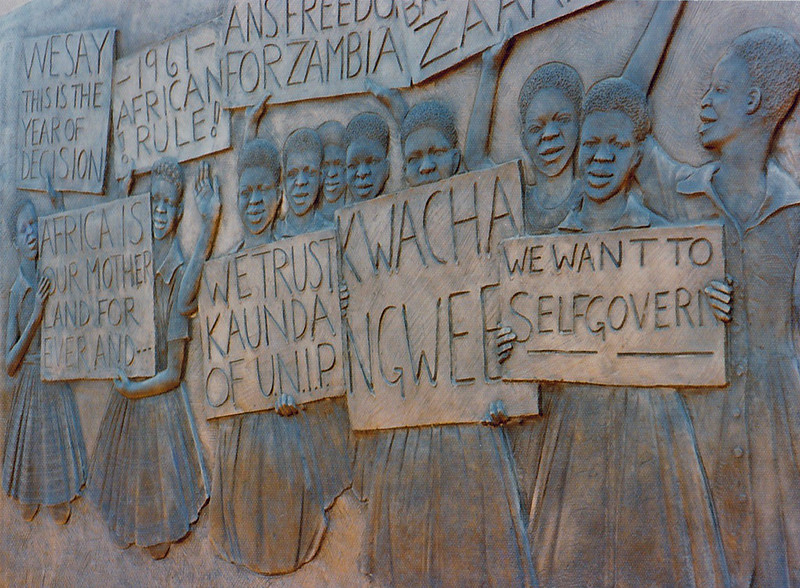

Each individual state’s independence is an important milestone, but the events of 1960 were part of a larger continuum of liberation. So many African leaders of countries not-yet-independent, like Julius Nyerere of Tanzania and Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia, were part of these ongoing, multilateral stories of Pan-Africanism, non-alignment, liberation struggles, and racial solidarity.

If we look at large-scale, transnational infrastructure projects, we see these “moments” of independence in their larger context. Projects born from colonial plans were realized in new ways by post-independence leaders through foreign investment and Cold War entanglements.

The Origins of a Term

The phrase “Year of Africa” was used first by O.H. Morris in January 1960 and put into practice by Harold Macmillan, then Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, during his “Wind of Change” speech on February 3, 1960, to the all-white South African Parliament. After touring British colonies in Africa, Macmillan had become increasingly convinced that “national consciousness” among Africans “was a political fact.”

If Macmillan and other colonial leaders seem to have predicted an inevitable decolonization, that was not their intent. The British leader had only begun to see African colonial holdings as liabilities by 1959.

Macmillan’s main concern was to lessen domestic and international criticisms of British colonial administration, especially after the brutality of the Mau Mau Uprising in Kenya (1952-1960) and the Nyasaland Emergency (1959) in what is now Malawi. He also worried that the Soviet Union and China would use independence struggles to gain footholds on the continent.

Independence and Pan-Africanism

Independence meant so much more than hoisting a flag. It was the culmination of immense struggle that emerged in the midst of a growing sense African nationalism, global racial solidarity, and multilateral partnerships.

As we look back on the Year of Africa, we should focus on the connections being forged, questioned, reimagined, and molded among African nations and their international partners, in part through conferences.

Conferences among African leaders convened in Tunis, Accra, Conakry, Addis Ababa, and Léopoldville in 1960 alone. They built on earlier multilateral, Third World meetings such as the Bandung Conference (April 18–24, 1955). Also known as the Asian-African Conference, it included 29 countries and represented 1.5 billion people, or 54% of the world population at the time. Its goals were to oppose colonialism and neocolonialism in all its forms.

Similarly, the All-African Peoples’ Conference (AAPC), created in 1958, hosted meetings in December 1958, January 1960, and March 1961. Its objectives were to achieve independence for all colonies, to strengthen already independent states, and to resist neocolonialism.

Another multilateral partnership among African states was the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), which was established on May 25, 1963, in Addis Ababa. This intergovernmental organization originally consisted of 32 signed members and had similar goals to those of the AAPC.

The OAU sought to encourage political and economic cooperation and integration among African states and to free the African continent from colonial and neocolonial control. Although considered ineffective because of policies of non-interference and an inability to enforce decisions without an official armed force, the OAU remains an important component of African independence stories. It eventually became the African Union (AU) officially in July 2002 and now boasts 55 member states.

Independence and International Partnerships

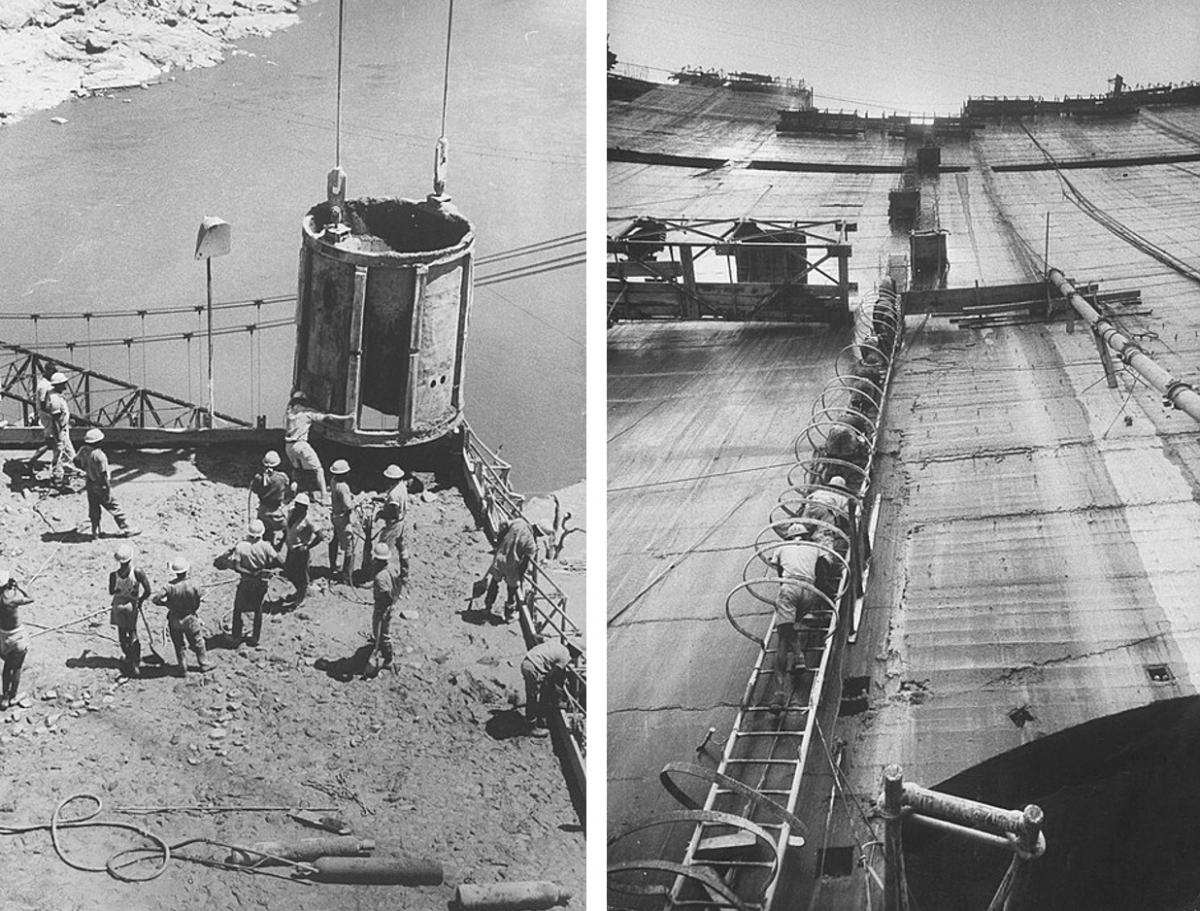

Telling the stories of decolonization through infrastructure building is another way to highlight the continuities of regional partnerships—even contested ones forged during colonial rule.

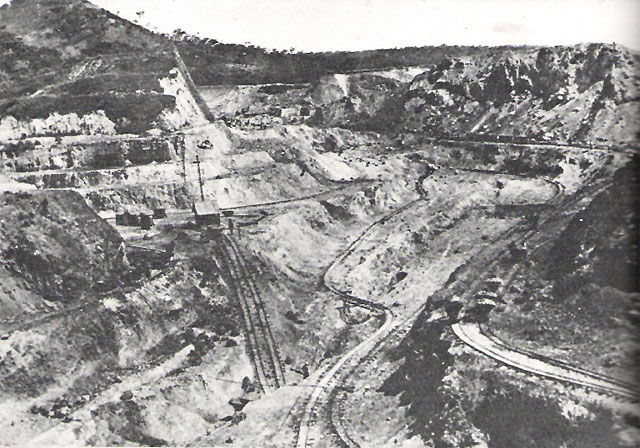

The Kariba Dam, located on the border of modern-day Zambia and Zimbabwe on the Zambezi River, is a good example. The story of this dam spans issues of regional tensions, colonial exploitation, and post-independence cooperation. The dam was envisioned and built between 1957 and 1959 in the then Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland (1953–1963) or Central African Federation (CAF), which consisted of a merged Southern Rhodesia, Northern Rhodesia, and Nyasaland, despite preexisting disparate relationships.

The Kariba Dam as seen from the Zimbabwean side.

The construction of the dam ran into several problems, mainly flooding and crumbled scaffolding; and 57,000 Tonga were forced out of their ancestral lands in the Gwembe Valley.

The dam is crucial to the copper mining industry in Zambia, which is one of the reasons it is accepted, despite the unpopularity of remnants of the CAF. It supplies approximately 6.7 million kilowatt-hours of electricity annually and is owned and operated jointly by Zambia and Zimbabwe. In recent years, the dam’s structural integrity has deteriorated, leading to outages and the risk of collapse.

Workers building the Kariba Dam in the 1950s (left). Workers scaling the dam walls during construction (right).

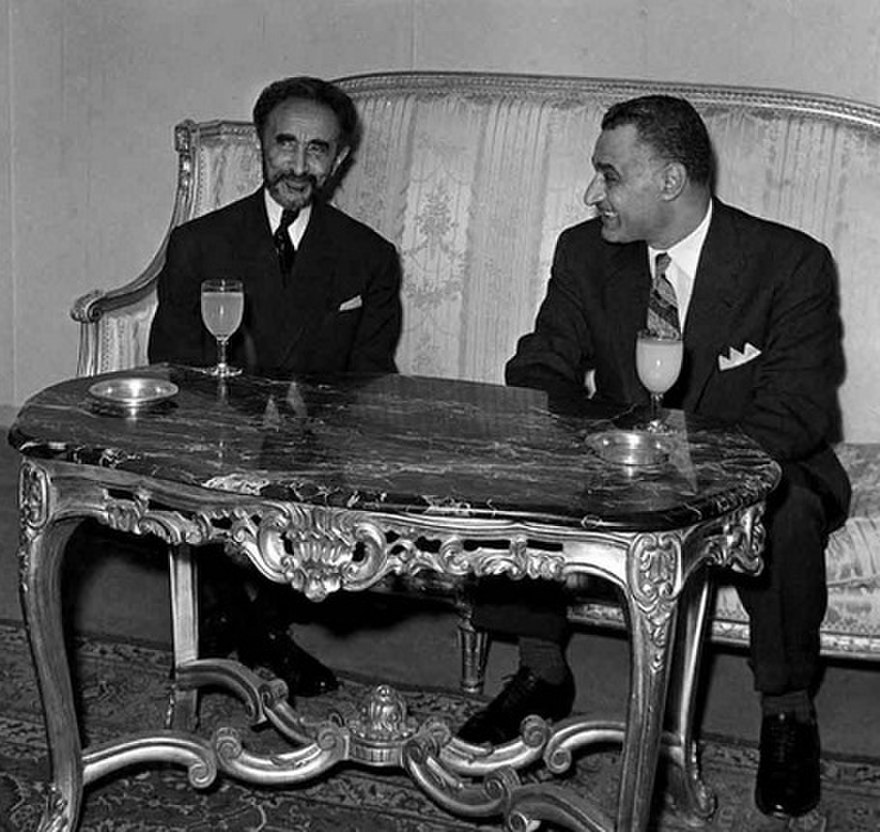

The Aswan High Dam in Egypt is another example. Funded by the Soviet Union, it was constructed between 1960 to 1970. It contributed positively both to the agricultural sector (allowing Nile floodwater to be controlled and stored) and to Egyptian independence from British “influence,” modernization propaganda, and Egypt’s place as a leader among developing nations in this period.

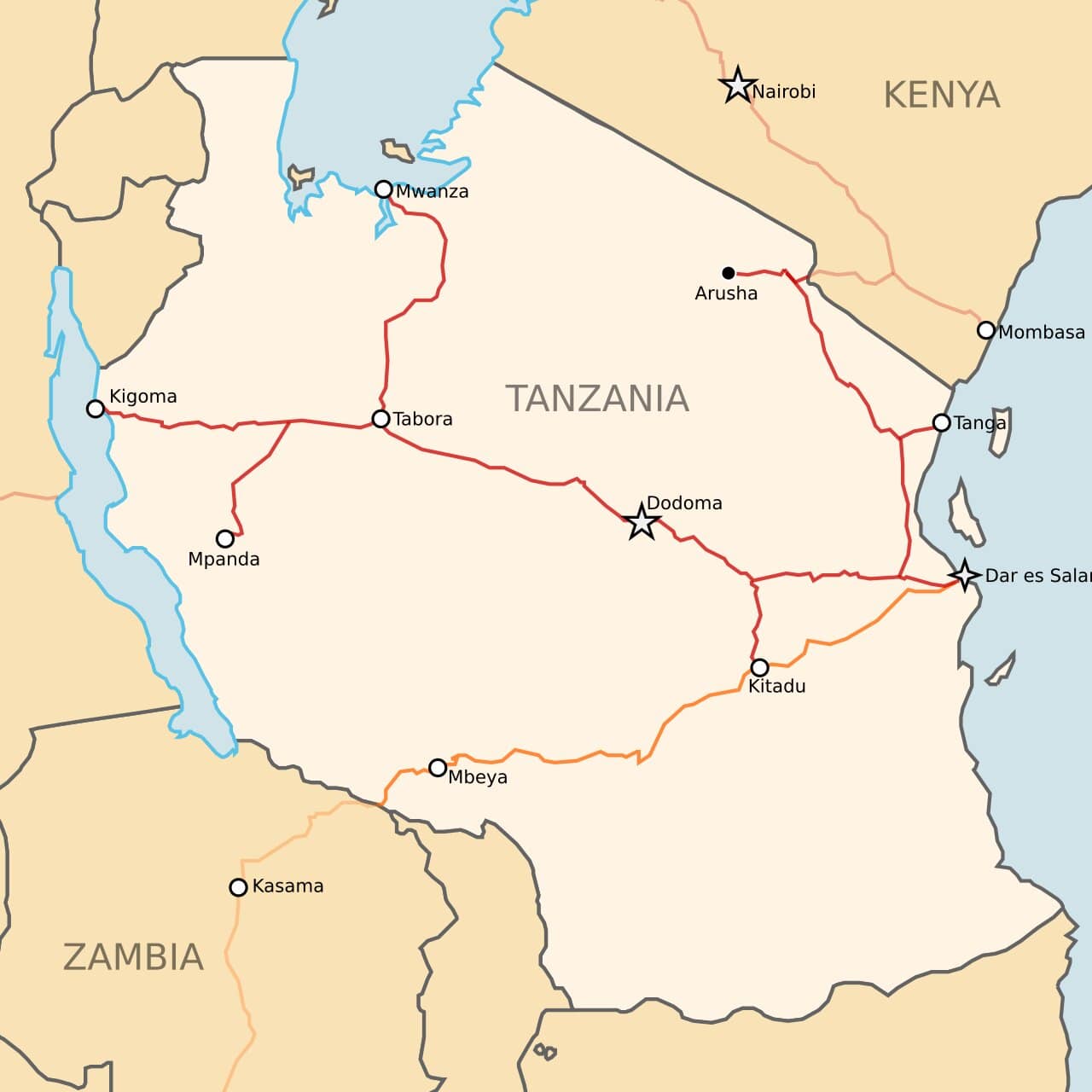

Later on, the construction of the 1,160-mile-long TAZARA Railway (1970–1976), which was funded by China, became a symbol of African modernity and liberation from the white supremacist regime in South Africa—if not in reality, certainly in legacy.

Soviet and Chinese involvement in Africa is best described as a competition resulting from divergent national and geostrategic interests and ideological and personal factors. China accused both the United States and the Soviet Union of neocolonialism and imperialism in the “Third World,” attempting to position itself as a revolutionary leader through a (largely imagined) racial solidarity.

In fact, China supplied military advisors who trained freedom fighters in Southern Africa and weapons to African struggles for independence. Many African countries saw China as both a political ally and a lucrative economic partner for development projects, despite the failures of the Great Leap Forward (1958–1962).

Liberation is Won, not Given

The period of possibility that followed the Year of Africa, despite failures to bring many possibilities to fruition, should not blind us to all the ways in which colonial powers continued to wreak havoc in Africa. European countries continued to try to sabotage, exploit, and control the African continent through direct and indirect means.

The French writer Jean-Paul Sartre coined the term “neocolonialism,” and Kwame Nkrumah used it in the preamble of the 1963 Organisation of African Unity Charter and again in his book Neo-Colonialism, the Last Stage of Imperialism (1965). Neocolonialism is defined as the use of economics, globalization, cultural imperialism, and/or conditional aid to “influence” an independent country covertly instead of overtly by brute force or political control.

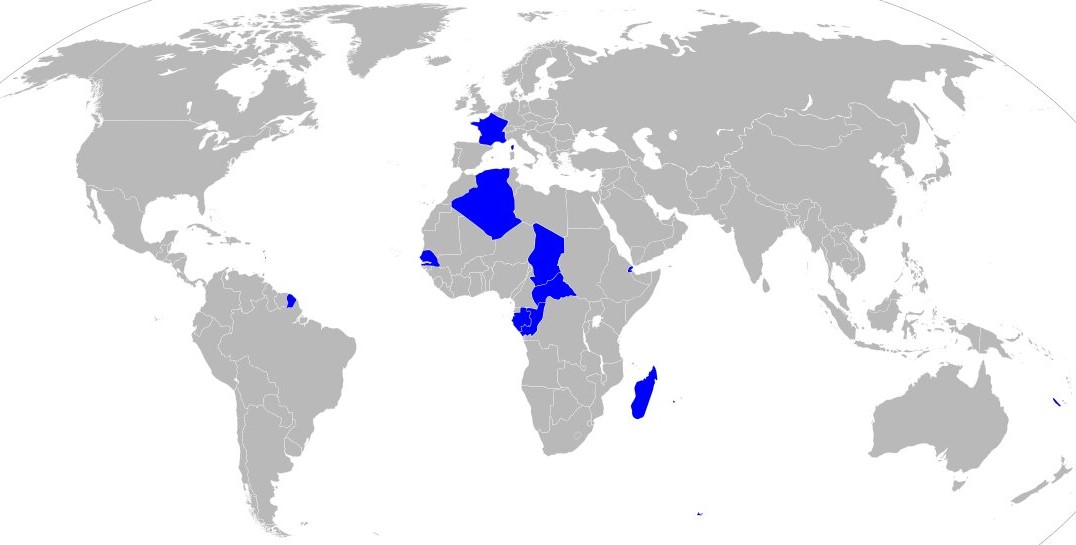

In the AAPC conferences in Tunis (1960) and Cairo (1961), the French Community, an association of former French colonies largely from Africa, was defined as neocolonialist in nature. In other cases, like in the Democratic Republic of Congo, independence was used by Belgian colonizers as a last-ditch effort to quell growing dissent.

Member states of the French Community in 1961.

Colonial powers continued to wreak havoc in Africa; they did not simply step back. Our history classes might tell students that individuals like Macmillan “gave” independence. But this terminology is antithetical to the realty of struggles for independence.

Liberation on the African continent was not a single event, and it was certainly not given. It was hard fought, won, and then continually tested by economic struggle, Western exploitation, and, in some ways, inadequate leadership.

Unfortunately, liberation from neocolonialism and racial hierarchies (both global and local) is, so far, an incomplete process. So perhaps a more accurate term for the various waves of decolonization on the continent would be the Generation of African Liberations or the Decades of African Freedom.

The Year of Africa was one moment in the complex processes of independence and decolonization. We see how African leaders and peoples cooperated, debated, and interacted with one another across state lines. These liberation struggles should be placed together, in context, instead of by case study or by individual independence day dates.

Congolese Rumba: Soundtrack to African Political Struggle Past and Present

by Emily Hardick

Watch a video or listen to audio of this piece.

Anyone switching on the radio or ducking into a bar anywhere on the African continent in 1960 would have been likely to hear, in their original Lingala and French, these lyrics set to an Afro-Cuban beat:

Independence cha-cha we have won!

Oh, we cha-cha are finally free!

Oh, Round Table cha-cha we have won!

Independence cha-cha here you are finally in our hands!

In the Year of Africa, the Democratic Republic of the Congo negotiated independence from Belgium to the rhythm of the country’s greatest export: Congolese rumba. The wildly popular and meaningful genre became a soundtrack to global change.

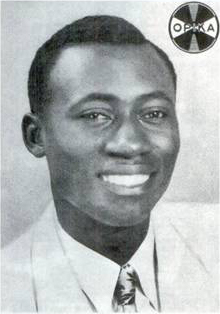

Indépendance Cha Cha, performed by Joseph Kabasele (“Le Grand Kallé” or Kallé Jeff) and his band African Jazz, is widely considered to be the first pan-African hit. Light-hearted and upbeat, the song narrates the 1960 Round Table Conference on Congolese Independence in Brussels.

Inspired by music from across the globe, Congolese rumba (also known by the French term musique moderne) was the singular sound Congolese performers used to record their aspirations of independence in the 1960s, to communicate political legitimacy in the immediate postcolonial era, and to memorialize the unfinished business of emancipation in our present day.

In short, Congolese decolonization was documented in song.

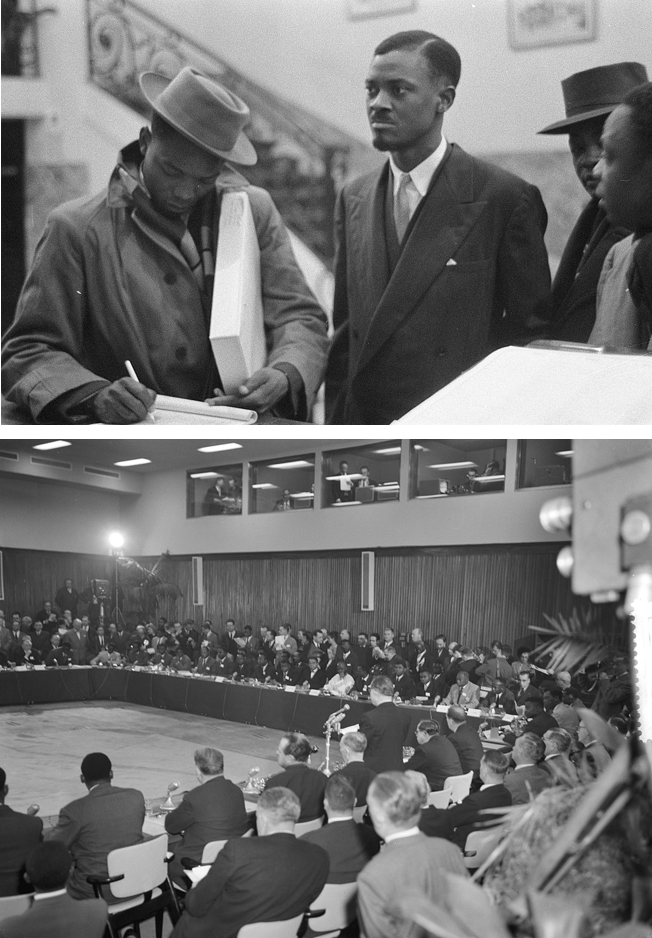

After 75 years of colonial oppression and mounting political agitation following World War II across what was then known as the Belgian Congo, Congolese politicians and Belgian administrators met in January 1960 to negotiate the colony’s fate.

The Congolese band, African Jazz, in a recording studio, 1961.

Grand Kallé and African Jazz, along with two members of rival musical group OK Jazz, accompanied the Congolese delegation to Brussels. The conference set Congo’s independence for June 30, 1960 in a shocking repudiation of the popular Belgian belief that Congolese independence would not be possible for another 30 years.

A sonic celebration of independence followed, asserting Congo as an artistic hub in its own right. The roots of Congolese rumba are found in Léopoldville (Kinshasa), where Cuban music records had first been imported in the 1930s and 1940s. Local musicians began to draw on the instruments and rhythmic progressions in Afro-Cuban music. Through the colony’s 1950s radio service, Congolese recordings popularized the cha-cha, merengue, and pachanga across the continent.

Congolese rumba influenced musical acts from South African icon Miriam Makeba to the popular “highlife” brass bands of Ghana and Nigeria. Rumba was a cosmopolitan style distinctly rooted in the Global South.

Congolese rumba influenced Miriam Makeba, pictured here in 1969, and many other African artists.

Many musicians of the period asserted that the structure of rumba had been exported to the Caribbean from Congo itself through the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. That rumba had made its way home demonstrated the endurance of Congolese culture and the connection between colonized peoples.

Congolese rumba linked African and Diasporic cultures, but Indépendance Cha Cha named Congo’s political parties and leaders:

Bolikango, Kasavubu with Lumumba and Kalondji

Bolya, Tshombe, Kamitatu, oh Essandja, Mbuta Kanza

As we look back on the Year of Africa, the euphoric unity among politicians memorialized in Indépendance Cha Cha now reminds us of the unfulfilled promises of decolonization.

In May 1960, Congolese citizens elected Patrice Lumumba and Joseph Kasavubu, prime minister and president respectively of the new Democratic Republic of the Congo. Lumumba, a radical nationalist, was soon ousted by Kasavubu out of fear of Lumumba’s anti-Western sentiments and as a result of soldiers’ mutinies and secessionist movements in the southern regions of Katanga and South Kasai.

Secessionists and UN and U.S. officials then conspired with the Belgian Foreign Ministry to assassinate Lumumba in January 1961, only seven months after independence.

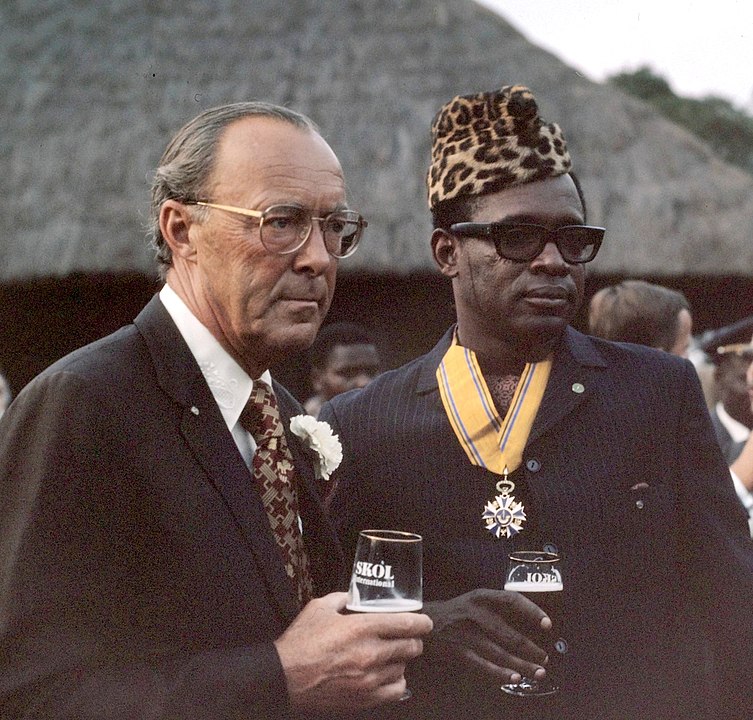

The Congo Crisis of 1960-1965 that followed ultimately led to an externally funded military coup and the installation of Joseph-Désiré Mobutu as head of state. Following Lumumba’s death, protesters converged on UN, U.S., and Belgian consulates around the world, demanding accountability for the death of Congo’s first popularly elected leader.

Mobutu, then president and authoritarian ruler of the Second Republic of the Congo, understood well the political uses he could make of both rumba and Lumumba.

Despite Mobutu’s complicity in Lumumba’s assassination, he quickly proclaimed the deceased prime minister the first “national hero,” and himself the second. Mobutu then commissioned a number of songs such as Lumumba, National Heroes (1967). This song was written by none other than Grand Kallé and African Jazz and the other giant in Congolese music, Franco (François Luambo Makiadi) and his band OK Jazz.

Members of OK Jazz during their 1961 trip to Brussels.

Lumumba, National Heroes established a link between Lumumba and Mobutu through lines such as:

Oh Mobutu, follow the road you forged with Lumumba

When Mobutu speaks, Lumumba is resuscitated …

In 1971, Mobutu established an authenticity campaign meant to uplift the country through cultural heritage, renaming the country Zaire and himself Mobutu Sese Seko in the process. Popular music and government became increasingly intertwined as the president called upon band leader Franco (of OK Jazz) to produce music in support of his government.

At the same time, music offered the means to critique power in postcolonial Zaire. Mbwakela, a genre of song infused with metaphor common in Congolese rumba, allowed Franco to maintain a privileged status within Mobutu’s government as well as operate as the president’s “only critic.”

Lumumba’s legacy, like Congo’s political independence as a whole, was cemented through the country’s subsequent artistic production. The “popular painting” style (also called urban or international art) that came to characterize Congo through the late 20th century canonized Lumumba as the martyr of African independence.

Outside the borders of the Republic of the Congo, Lumumba continued to inspire reflection on the incomplete process of decolonization, as in famed Martiniquais poet Aimé Césaire’s play A Season in the Congo.

Rumba’s power reached an apogee in 1974, when the music festival Zaire 74 hosted prominent musicians such as James Brown and B.B. King, who performed alongside Zairians such as Franco and Tabu Ley Rochereau (of African Jazz).

The festival, which accompanied a heavily promoted fight between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman (known as “The Rumble in the Jungle”), acknowledged rumba as the country’s most important cultural export. Held at an economic and cultural peak of Mobutu’s regime, music functioned as a triumphant signal of postcolonial success.

The high did not last long. The economic decline of the 1980s, political violence after Mobutu’s fall in 1997, and the continued external exploitation of Congolese resources by Western powers plagued and plague the nation to this day.

In 2011, Belgian-born rapper Baloji released a reworking of the most famous song of 1960, Le Jour d'Après / Siku Ya Baadaye (Indépendance Cha-Cha). Baloji, who is of Congolese descent, comments on the DRC’s contemporary problems through reference to its past:

I covered this unifying song

Symbol of the credulity of our premises …

But for our democracies to progress

We must learn from the errors of youth …

Filmed in Kinshasa, Baloji’s video invokes Congolese rumba as a symbol of Grand Kallé’s once-joyous, now aged, proclamations of victory. Yet Baloji’s rendition contains a message of hope. Rumba, through all, remains a key instrument to critique oppression and galvanize the people.

The Year of (Pan) Africa: Global Dimensions of African Independence Movements

by Damarius Johnson

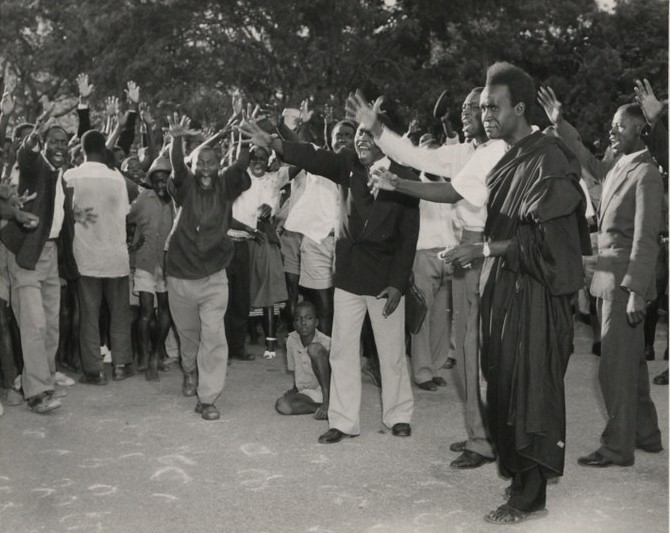

1960 was the heyday of Pan-Africanism, the social, political, and economic partnerships between continental Africa and its diaspora.

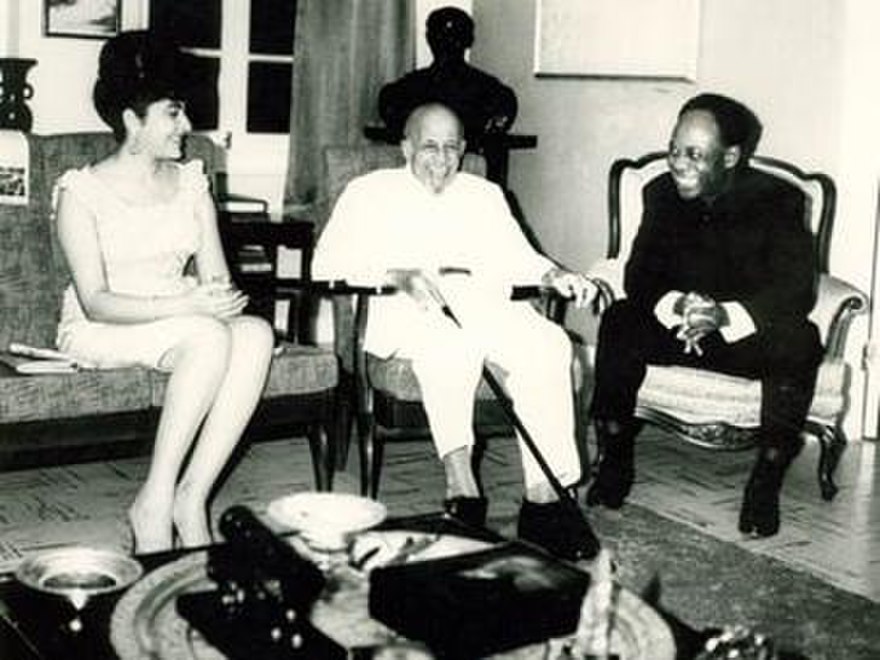

Kwame Nkrumah and Martin Luther King Jr in Ghana.

Throughout the 1960s, Civil Rights activists in the United States strengthened the ties between the anticolonial movements of West and Central Africa and the American freedom struggle against legal segregation and racial violence. African Americans were active participants, collaborators, and advocates in the resistance struggles and emancipatory celebrations of African independence.

These expressions of Pan-Africanism reflect the activist networks and cultural productions generated throughout the 1960s. The Year of Africa marks the emergence of new African nations from the resistance struggles of preceding decades.

The examples of Ghanaian and Congolese independence, both of which occurred in 1960, attest to the significance of African nation-building for continental and diasporic African communities.

Ghana

In the evening hours of March 5, 1957, Kwame Nkrumah, prime minister of the British Gold Coast Colony, stood before an audience of nearly 50,000 to announce the birth of a new African nation, Ghana. Nkrumah, who later served as Ghana’s first president, proclaimed “Ghana is free forever!” in his independence address to an international audience comprised of Ghanaian citizens and African American activists.

The first cabinet of Kwame Nkrumah (center bottom row) as Prime Minister of Ghana, 1957.

Among the attendees of Ghana’s independence were African American luminaries: Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Coretta Scott King, labor activists A. Philip Randolph and Lester B. Granger, congressmen Charles Diggs and Adam Clayton Powell, diplomat Ralph Bunche, NAAACP Executive Secretary Roy Wilkins, publisher John H. Johnson, and Howard University President Mordecai Wyatt Johnson.

This cross section of African American witnesses to Ghana’s independence indicates the significance of Ghanaian nationalism for the African diaspora. Ghanaian independence represented a beacon of hope for African Americans who engaged in their own domestic resistance struggles against Jim Crow segregation and racial violence.

Nkrumah’s administration also recruited African Americans to contribute to the work of developing independent Ghana. In the early years of Nkrumah’s administration, African Americans expatriated to Ghana as journalists, educators, and government officials who disseminated Nkrumah’s ideas about Pan-Africanism and African unity to Ghanaian citizens.

The groundwork for Nkrumah’s ties with African Americans formed in the decades before 1960.

Kwame Nkrumah attended Lincoln University (1935-1939) where University President Horace Mann Bond mentored him. Bond’s son Julian Bond become an important civil rights activist and co-founder of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

As a supplement to his undergraduate studies, Nkrumah also discovered the Pan-African ideas of W.E.B. Du Bois and Marcus Mosiah Garvey, founder of the United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). These experiences had a great impact on his administration of independent Ghana.

The symbolism of the Ghanaian flag reflected the influence of African American Pan-Africanists. The Ghanaian flag incorporated the red, black, and green colors and horizontal stripes of the U.N.I.A. flag.

The United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) flag (left). The Ghanaian national flag (right).

In 1945, Nkrumah and Du Bois hosted an international gathering of African intellectuals, students, and activists for the fifth Pan-African Congress in Manchester, England. The international gathering of African students, Caribbean activists, and African American intellectuals included many future leaders presidents of independent African nations, including Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia, Nnamdi Azikiwe of Nigeria, and Hastings Banda of Malawi.

By 1960, when Ghana achieved its independence, Nkrumah’s political résumé included strong relationships with African diaspora communities in the Caribbean, United States, and Europe.

Ghanaian independence represented the joyous occasion of political achievement to the African world, yet it also benefitted from the symbolism and practical efforts of Caribbean and African American Pan-Africanists to develop a new nation.

The Republic of the Congo

Congolese independence, like Ghanaian independence, inspired African Americans to resist white supremacy within the United States. In return, African Americans expressed their support for the anticolonial freedom struggle in Congo.

On June 30, 1960, Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba, pictured here at the Round Table Conference in Brussels, declared the independence of the Republic of the Congo from the former Belgian Congo Free State (top). The Round Table Conference in Brussels, 1960 (bottom).

African Americans also fostered cultural connections to Congo that predated independence. The career of African American poet, musician, and NAACP Executive Secretary James Weldon Johnson demonstrates these interconnections.

Johnson is renowned for writing “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing,” a beloved song of the Civil Rights Movement, known today as the Black National Anthem. It functioned as a protest song, lamentation, and assertion of African American cultural pride that gathered new meanings within African American communities throughout the 20th century and into the present.

Although James Weldon Johnson is best-known for his African American cultural production, he had an ongoing interest in African history and culture. In 1903, he wrote the wildly popular “Congo Love Song” that challenged Western claims of African barbarity by narrating a romantic encounter in which a Congolese woman woos her suitor into marriage. In his later years, Johnson wrote a pamphlet titled “Native African Races and Culture” that traces African American history to the language groups and ethnic communities in continental Africa.

By June 1960, when Ralph Bunche, NAACP board member and United Nations diplomat, attended Congo’s independence celebration, African Americans had established a long history of deep engagement in Congo.

In Black newspapers such as the New York-based Amsterdam News, the Chicago Courier, and the Baltimore Afro-American, Africans Americans decried the violent Belgian response to Congolese anticolonialism.

The Year of Africa is the crowning achievement of continental African nation-building and African American Pan-Africanism. In a single year, 1960, the fulfillment of continental Africa’s protests, petitions, and armed resistance struggles intersected with African American explorations of African histories, cultures, and politics, and the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1960.

African independence has meant a symbolic, pragmatic, and collaborative effort toward a global Black freedom struggle.

Elkins, Caroline. Imperial Reckoning: The Untold Story of Britain's Gulag in Kenya. Toronto: CNIB, 2008.

Fanon, Frantz. Toward the African Revolution: Political Essays. New York: Grove, 1952.

Lee, Christopher J. Making a World after Empire: The Bandung Moment and Its Political Afterlives. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2010.

Monson, Jamie. Africa's Freedom Railway: How a Chinese Development Project Changed Lives and Livelihoods in Tanzania. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009.

Phiri, Kings M. Malawi in Crisis: the 1959/60 Nyasaland State of Emergency and Its Legacy. Zomba, Malawi: Kachere, 2012.

Sartre, Jean-Paul. Colonialism and Neocolonialism. Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 1964.

Tischler, Julia. Light and Power for a Multiracial Nation: the Kariba Dam Scheme in the Central African Federation. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Collinet, Georges. “Hidden Meanings in Congo Music.” Afropop Worldwide, December 21, 2011. https://afropop.org/audio-programs/hidden-meanings-in-congo-music.

Gondola, Didier. The History of Congo. Westport, Conn: Greenwood, 2002.

Kazadi, Pierre Cary (Kazadi wa Mukuna). “The Genesis of Urban Music in Zaïre.” African Music 7, no. 2 (1992): 72–84.

Nzongola-Ntalaja, Georges. Patrice Lumumba. First edition. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2014.

White, Bob W. Rumba Rules: The Politics of Dance Music in Mobutu’s Zaire. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2008.

Iwa Dworkin, Congo Love Song: African American Culture and the Crisis of the Colonial State (University of North Carolina Press, 2017)

Kevin K. Gaines, American Africans in Ghana: Black Expatriates and The Civil Rights Era (University of North Carolina Press, 2006)

James Meriwether, Proudly We Can Be Africans: Black Americans and Africa, 1935-1961 (University of North Carolina Press, 2002)

View the video or listen to the audio version below of "Congolese Rumba: Soundtrack to African Political Struggle" written by Emily Hardick.