From the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries, the labor of millions of enslaved Africans generated tremendous wealth for an elite community of slave owners, slave traders, and political rulers in Europe, West Africa, and Atlantic societies. Simultaneously, formerly enslaved individuals and their descendants petitioned for compensation, recognition, and material support, known today as reparations.

The controversy surrounding reparations—about whether national governments owe apologies for transatlantic enslavement, material support for generational disadvantages of racial discrimination, or financial payments to formerly enslaved persons—spans three centuries.

Ana Lucia Araujo’s Reparations for Slavery and the Slave Trade: A Transnational and Comparative History chronicles the history of the reparations debate by exploring the demands of abolitionists, formerly enslaved individuals, activists, and international organizations for reparations from post-slave societies across the Atlantic, particularly in the United States, Brazil, and Cuba.

Araujo’s history offers a compelling review of the rationales made for reparations payments, the historical actors who made such claims, and historical events that motivated their political demands. This is not a book about policy proposals for addressing the legacies of enslavement, but rather a historical analysis of the debates surrounding it.

While Atlantic slavery spans centuries, the use of the term “reparations” to describe ex-slave grievances is relatively new. The term gained popular use after Germany issued financial payments for damages caused by World War I. Enslaved persons, abolitionists, activists, and politicians previously used many other terms, such as “redress, compensation, indemnification, atonement, repayment, and restitution,” to convey the same idea.

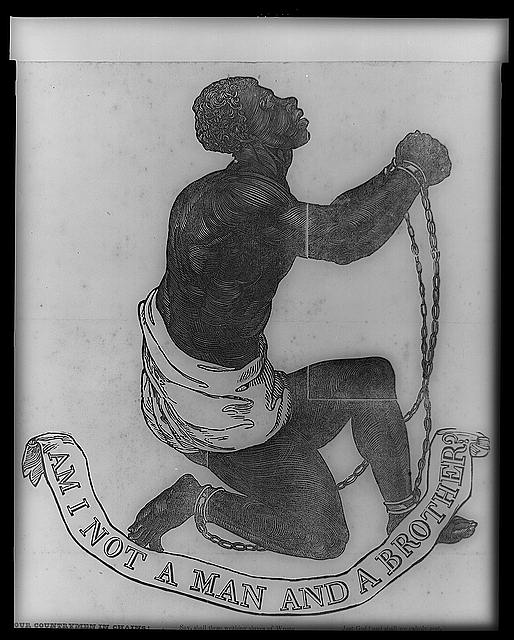

American Anti-Slavery Society, 1837

Araujo’s history of reparations claims begins with a discussion of transatlantic slavery. Across three centuries, millions of enslaved Africans were kidnapped and captured during wars and slave raids in West Africa, subjected to treacherous overland travel from the African interior to coastal slave ports, and then held in the treacherous holds of slave ships. Successive generations of enslaved people born in the colonies of the present-day United States, Brazil, Cuba, and Colombia, experienced racial exclusion and economic deprivation specifically because of their heritage as enslaved persons.

Simultaneously, immense wealth circulated among rulers of African ethnic empires, European slave traders, and wealthy colonial slave holders. Transatlantic slavery complemented other trading in commodities such as beer, ivory, and gold. Enslavers generated profits not only from unpaid wages to enslaved Africans but also from revenue gained from highly valuable goods such as sugar and cotton.

No post-slavery nation has issued financial reparations to enslaved persons or their relatives to date, yet slave holders across Atlantic societies received financial compensation for the loss of wages due to decline of the slave trade.

Perhaps the most visible insurrection of Africans in the nineteenth century Atlantic world, the Haitian Revolution, resulted in the formation of an independent African nation (Haiti) in 1804. However, in exchange for formal recognition of its independence in 1825, Haiti agreed to issue reparations to cover financial losses incurred by France from the time of Haiti’s independence.

Likewise, the government of the United Kingdom compensated slaveowners after the abolition of slavery in British colonies, and those payments only ended in 2015.

During the Reconstruction Era (1865-1877) in the United States, formerly enslaved persons petitioned for newfound citizenship rights rather than reparations for unpaid labor. In the late nineteenth century, Congress considered several bills to establish financial compensation for formerly enslaved persons. They all failed.

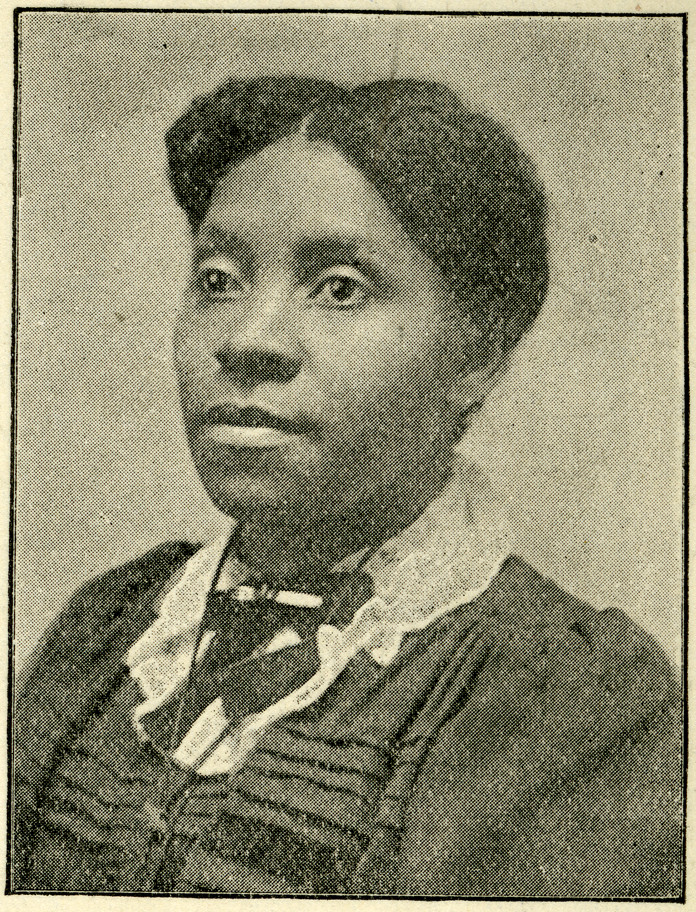

The largest and most substantial organization to work for financial reparations was the National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty and Pension Association, founded in 1897. Two African Americans led the organization: a formerly enslaved abolitionist, Callie D. House, and minister and educator Isaiah H. Dickerson.

Callie House explained her motivation thus: “We the Ex-Slave feel that if the government had a right to free us she had a right to make some provisions for us as she did make it soon after our Emancipation she ought to make it now.”

As the members of the National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief Association drew greater attention to the need for ex-slave reparations, the Association faced increasing opposition from federal officials who sought to undermine the operations of the Association. Among federal techniques was the disruption of mail correspondence between the Association and its members.

The Association faced ongoing lawsuits alleging the financial impropriety of its leadership. In 1917, Callie House was convicted of mail fraud and sentenced to one year in prison. House’s imprisonment prompted the decline of the Association as the remaining organization branches focused on African American mutual aid rather than reparations claims.

In Cuba and Brazil, countries with much higher concentrations of African citizens, no parallel organization for national reparations developed during this period. In the 1880s, Cuba and other French and British Caribbean territories such as Martinique or Guadeloupe, gradually abolished the slave trade. The post-slavery economy generated immense competition among freed Afro-Cubans and immigrant populations of Spanish and Chinese laborers. Not granted financial compensation and lacking marketable skills, many Afro-Cubans secured marginal wages that prevented access to land ownership and long-term economic viability.

During the 1960s, the local contexts of reparations movements varied widely. In Cuba, a 1959 revolution instituted land reforms that increased black land ownership. During the Civil Rights era in the United States, African Americans focused primarily on gaining legal rights rather than petitioning for reparations. In Brazil, the displacement of João Goulart by a military coup suppressed the reparations debate until 1985.

During the 1980s, international organizations advocated for the formal recognition of enslavement and its effects, pressuring post-slave societies to rectify the historical abuses suffered by enslaved persons and their descendants. Amid domestic and international demands for reparative aid, President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 which authorized financial reparations to Japanese American victims of internment during World War II.

President Reagan signs the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 in an official ceremony.

International cooperation in the reparations debate reached its apex at the 2001 United Nations World Conference Against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia, and Related Intolerance. At this gathering, a coalition of human rights groups, attorneys, and activists drafted reparations claims that addressed the wide-ranging effects of discriminatory behavior over the years.

Araujo concludes her study by emphasizing that reparations claims call attention to the historical horrors of enslavement and the tangible legacies of slavery. Throughout the text, she underscores that reparations campaigns made by formerly enslaved Africans in the Atlantic were largely unsuccessful.

Other aggrieved communities in the Americas and Europe received material, financial, and symbolic reparations. However, drawing attention to this differential outcome does not explain why the reparations demands made by enslaved Africans and their descendants were rejected or why, in many cases, post-slavery societies tend to avoid confronting the legacies of enslavement.

Reparations for Slavery and The Slave Trade is an insightful and expansive history of enslavement that reveals the interconnected nature of the Atlantic world from the origins of enslavement to the present day.