When Idi Amin, commander of the Ugandan Army, seized power in Uganda on 25 January 1971, there was hope among many Ugandans that a new beginning beckoned.

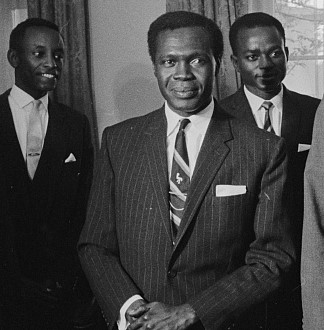

Amin replaced Milton Obote, who had been in power since independence in 1962 and who had presided over a steady slide toward authoritarianism. Obote also abolished Uganda’s constituent kingdoms – a key source of pride and identity for millions – in favour of a unitary state. His putatively socialist economic policies had become widely discredited.

As a result, Amin’s declaration that Obote had been overthrown and that the army had taken over guardianship of the nation was greeted with relief in many quarters.

Amin’s coup d’état was in some respects the culmination of Uganda’s tumultuous decolonization. Nationalist politics in the 1950s had been ferociously contested along religious, ethnic, and regional lines, and fractures remained – indeed deepened – during the 1960s. Many who perceived the civilian political class as increasingly illegitimate welcomed the seizure of power by a supposedly apolitical professional soldier.

However, neither patriotism nor altruism motivated Amin; rather, personal circumstances moved him to act. His own position had become perilous in the months prior to the coup as his relationship with Obote deteriorated. He had been demoted from his former post as commander of the Ugandan armed forces, and he had recently learned of his impending arrest on the charge of misappropriating public funds.

In any case, following a brief honeymoon period in which the new regime enjoyed some public support, the nature of Amin’s government soon became appallingly clear. He carried out bloody purges of soldiers from rival ethnic groups, while his brutal security forces clamped down on dissent and increasingly unleashed violence with impunity.

Milton Obote, Prime Minister and later President of Uganda 1962-71 and 1980-85.

He summarily expelled the Ugandan Asian community, numbering in the tens of thousands, and distributed their wealth and property to his own people. His administration was chaotic, with atrocities carried out by individuals loyal to him and thus acting beyond what remained of the law. Between 1971 and 1979, several hundred thousand people died as a result of his tyranny, and many Ugandans fled the country.

Amin was an extreme example of a shift toward military rule across the continent, and of the political and economic crises confronting many African states in the 1970s following the optimism of decolonization in the 1950s and 1960s.

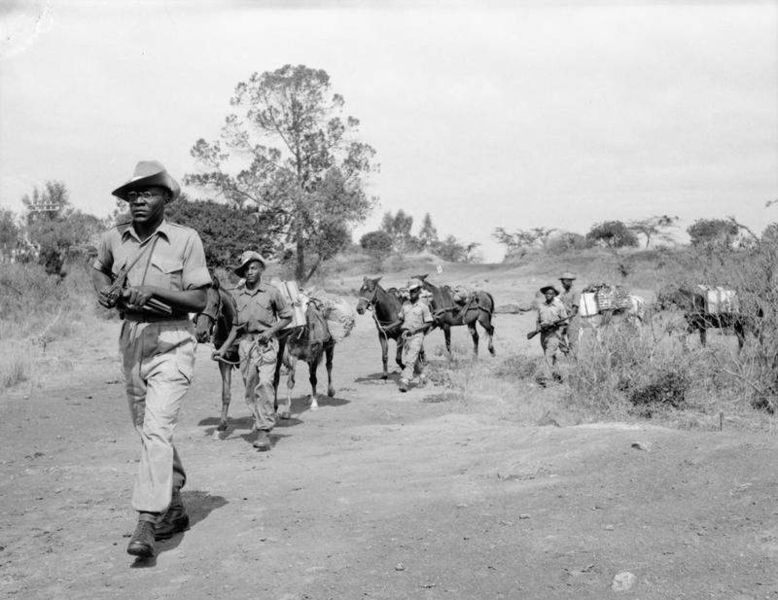

To some extent, Amin could be seen as representative of precolonial military culture, the resurgence of an idea deeply rooted in the region that military leaders made the best political leaders, and that army and state were indelibly intertwined. Yet Amin himself was also very much the product of British colonial rule. As a young semiliterate man from the Kakwa ethnic group in the far northwest of the Ugandan Protectorate, he had been recruited into the King’s African Rifles, the British colonial regiment in East Africa.

It was British policy to target for military recruitment communities on the peripheries of their territories, and groups identified as “martial” in culture and physiology. Idi Amin served the British with some distinction, including in Kenya during the Mau Mau uprising in the 1950s. He drew praise for his vigour and loyalty from his commanding officers who nonetheless commented that he was intellectually challenged – not untypical, and usually racially framed.

Perhaps for those very reasons, at least in part, Amin – while initially supported by the British, who saw him as an ally compared to the leftist Obote – quickly became hostile to Britain and to the West in general. By the mid-1970s, he gravitated toward the Islamic world in diplomatic terms, embraced his Muslim identity, and became particularly close to Libya’s Muammar al-Qaddafi.

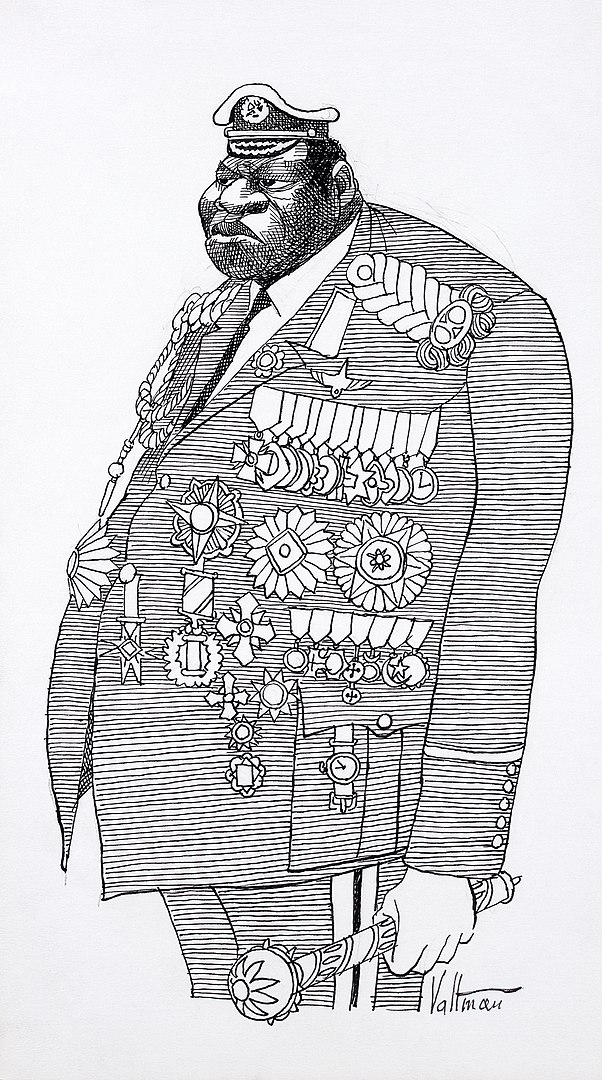

After the British Government severed diplomatic relations with Uganda in 1977, Amin awarded himself a new title – Conqueror of the British Empire – and enjoyed taunting his former colonial masters.

Almost as important as any actual policy shifts to understanding Idi Amin is the image-making that went on around him in the course of the 1970s. Right from the outset following his coup, Amin projected himself as a man of the people, cultivating a folksy, jocular persona behind the bemedaled uniform of the Field Marshal and President for Life.

Western media, on the other hand, framed him as a bloodthirsty clown and unstable despot. He was thus positioned in a canon of European stereotypes about African leaders stretching back to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Thus was the figure of Amin racialized in the bluntest of terms, and he himself became a byword for the bizarre cruelty of African military regimes.

While there were various plots against Amin, as well as several assassination attempts, in the end he was brought down by a foreign policy blunder – an ill-advised invasion of Tanzanian territory, which led to the Tanzanian army’s uncompromising response alongside Ugandan forces in exile. Within weeks, his army was crushed, and he fled into exile, first to Libya and later to Saudi Arabia, where he remained for the rest of his life. He died in 2003.

In the short term, Amin left Uganda in turmoil – a succession of unstable governments through 1979-80, and ultimately the return of Milton Obote following the rigged election of 1980. Civil war erupted in the early 1980s and the regime popularly known as ‘Obote II’ involved more death and destruction than the whole of Amin’s tenure. Obote was overthrown for the second and last time in 1985. Six months later, the current regime – the National Resistance Movement under Yoweri Museveni – seized power.

Amin’s era was a traumatizing period for millions of Ugandans. In many ways, Uganda has lived under the shadow of Amin ever since, even though the majority of Ugandans now have no direct memory of his regime.

At the same time, the declining popularity of the current incumbent, Yoweri Museveni, who has been in power for an extraordinary thirty-five years, means that at least some Ugandans have softened their view of Amin and regard him as something of a patriot and a nationalist by comparison. That is a remarkable development and certainly an indictment of Museveni.

In the longer term, Amin’s reign marked a decisive shift toward the politics of violence in Uganda and the militarization of politics, most visibly manifest in the proximity of the army to political power and in the expansion of the security state. Since Amin’s coup in January 1971, Uganda has not had a peaceful transfer of power.

More broadly, Amin’s seizure of power and subsequent presidency belongs to a period in early African postcolonial history. It was a time in which soldiers wrested government from civilian control – a phenomenon that was emblematic of political instability and the economics of inequity and theft, with which the continent has struggled for decades.