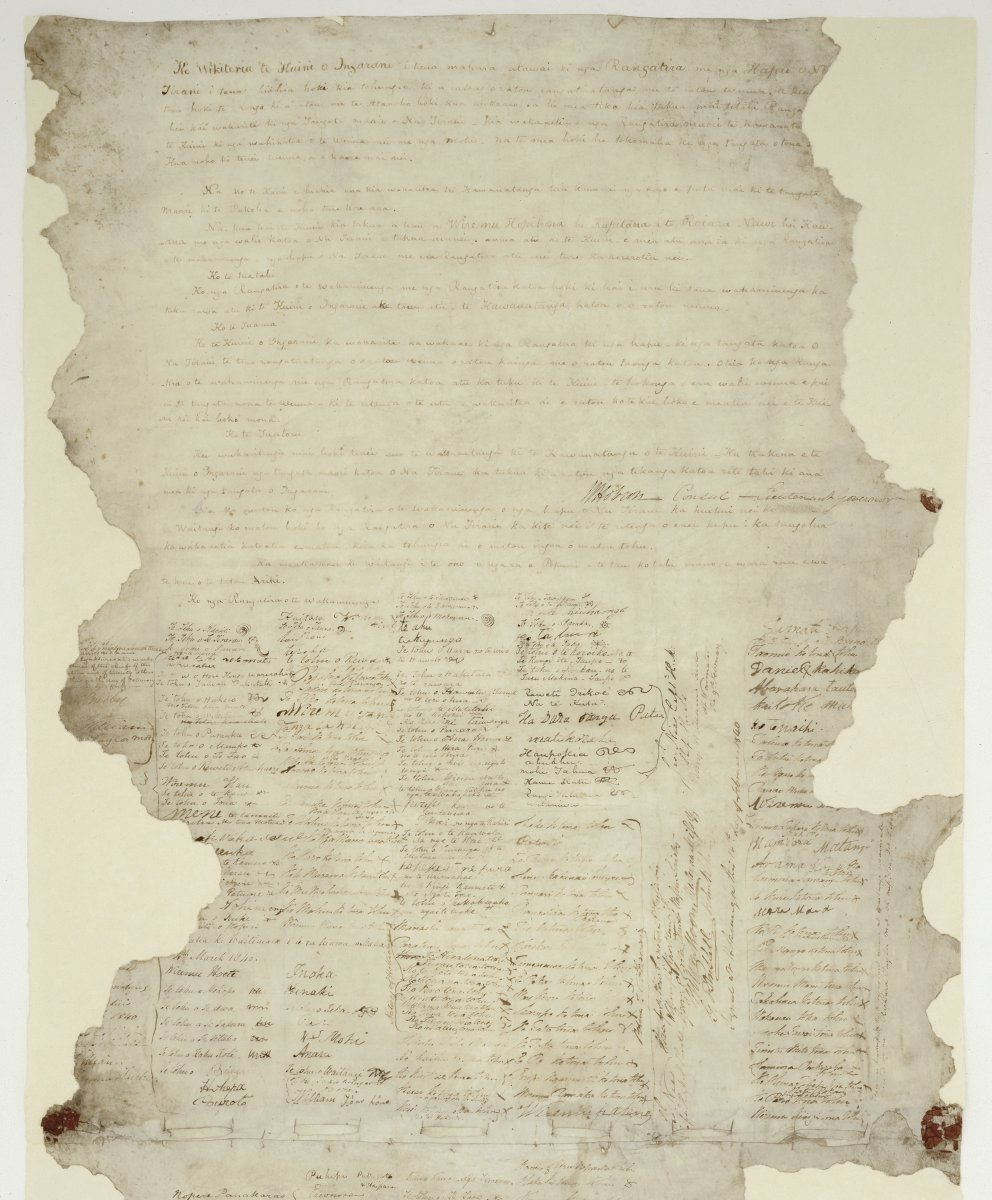

On February 6, New Zealanders will mark Waitangi Day on the 180th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi. Following the treaty, the British Crown claimed sovereignty over the country, citing what it claimed was the free consent of over 500 rangatira (chiefs) and the tribal communities they represented.

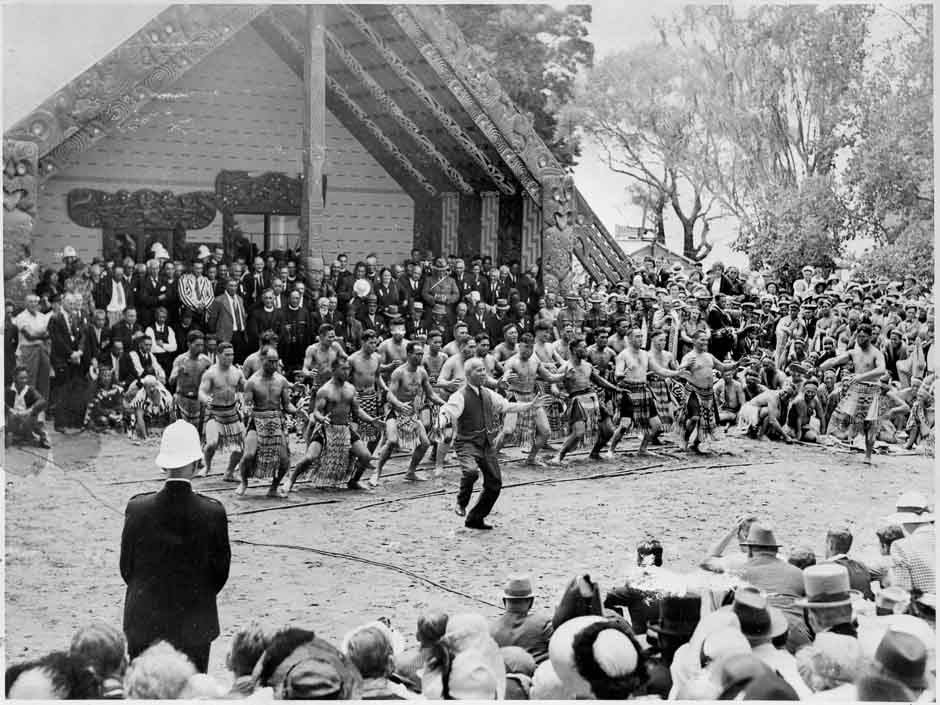

A 1939 reconstruction of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi.

The first 50 of these chiefs gave their consent to the treaty at Waitangi on February 6, 1840. However, the treaty also guaranteed rangatira their chiefly authority and promised to protect Māori ownership of land and other resources. Even at the time, there was some confusion about what was being transferred to the Queen and what was being retained. The meaning of the treaty was contested in 1840 and remains so.

Since 1840, New Zealand has evolved from a British colony to an independent nation-state, becoming increasingly diverse, with over a quarter of its population today born overseas. As our national day, Waitangi Day now needs to serve as a symbol for all these different communities.

In contrast with many other countries, New Zealand does not have a clear-cut founding date. Unlike Australia, New Zealand was not created as a result of separate colonies joining in a federal union and, unlike the United States, it never experienced a war of independence. There are no points in time when New Zealand formally separated itself from Great Britain or established a new constitution.

The only anniversary of national origins that includes the European population must go back to 1840, when William Hobson arrived to be the first governor and colonists stepped ashore to establish their own settlements. But which day in 1840?

Wellington and Auckland have two holidays in the weeks prior to Waitangi Day. These Anniversary Days, as they are called, are associated with the Wellington and Auckland provinces. Although the provinces were abolished in 1876, the holidays themselves live on.

Charles Heaphy’s rather romantic depiction of 1842 Wellington.

Wellington’s Anniversary Day celebrates the arrival in January 1840 of the first group of settlers sent by the New Zealand Company as part of a grandiose scheme to colonize the New Zealand islands. Auckland’s Anniversary Day marks Hobson’s arrival in New Zealand, a week before the treaty was signed. Auckland’s Anniversary Day has been celebrated since 1842.

In contrast, Waitangi Day was only made a national public holiday in 1974.

Originally, the government designated the day as “New Zealand” Day, in the hopes that it would become a unifying event that brought together Māori and non-Māori in a celebration of the country’s increasing multiculturalism. But Māori were not prepared to give up the day’s association with the treaty and it soon reverted to Waitangi Day.

Far from being a source of unity, Waitangi Day quickly became associated with a growing indigenous protest movement. Some New Zealanders wanted to remember the Treaty of Waitangi for the promises made to their ancestors, promises broken almost as soon as the treaty was signed.

Other New Zealanders would prefer to remember New Zealand’s history as a triumph of progress, where hardy and resourceful European settlers created a new society in the wilderness. For them, the treaty was either irrelevant or an embarrassment.

These divisions are as old as the Treaty of Waitangi itself. The treaty marked a high point in British humanitarianism, when the movement that had successfully achieved the abolition of slavery in the British Empire in 1833 turned its attention to the plight of aborigines.

By then, it was well known that European colonization inevitably led to the decline of aboriginal peoples. In a major enquiry by the British Parliament in 1837, a commission determined that further colonization should not take place, because of the risks to indigenous peoples. Their rights to life, property, and sovereignty were sacrosanct.

Unfortunately, this enthusiasm for the rights of aborigines occurred just when others in England decided that large-scale colonization might just be the solution to social and economic problems of the day.

Edward Gibbon Wakefield, a leading economist and social reformer, saw New Zealand as the ideal location for testing these ideas. Wakefield and his supporters became locked in an intense and bitter conflict with missionary-led humanitarians over New Zealand’s future.

In 1839, the New Zealand Company dispatched an expedition to purchase land, sold land it didn’t possess to prospective migrants, and packed them off in immigrant ships to New Zealand. Reluctantly, the British government decided it would have to intervene and Hobson and his treaty were intended to constrain the Company and to create a government that would meet the needs of both Māori and settlers.

From 1840 to the present, the status of the Treaty of Waitangi has reflected the ongoing tussle between these two founding principles. As European settlers became more dominant, the memory of the Treaty of Waitangi became less significant in public life. When governments were forced to acknowledge it, they interpreted it as evidence of benign colonization.

In contrast, Māori used the Treaty of Waitangi to remind New Zealand of the promises made (and broken) in 1840, the loss of Māori land, social and economic marginalization, and the invasions and confiscation of Māori land which took place in the 1860s. More recently, the Treaty of Waitangi has been used to challenge the legitimacy of the New Zealand state itself, in arguments that sovereignty was not transferred by the chiefs in 1840.

Despite these challenges, Waitangi Day remains New Zealand’s national day and the Treaty of Waitangi has re-emerged as an important test of the country’s relationship with its indigenous peoples.

The Waitangi Tribunal was established in 1975 to make New Zealand’s legal system more compatible with the treaty’s promises. Since 1985, the Tribunal has re-explored the colonial past and a series of Treaty settlements have recognized Māori tribal identities making some, but not all, tribes significant players in New Zealand’s regional economies.

For some, Waitangi Day has gained new importance: it is a symbol of how far the country has come since 1840. For many Māori, Waitangi Day is a reminder of how far the country has yet to go. At least, once a year, the treaty can no longer be completely ignored.