Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the Ukrainian army has proven itself mighty and tenacious to an international community that may have previously thought them quiet and unassuming. But the fierce Ukrainian army has an historical prototype in the Zaporozhian Cossacks, a daring and fearsome people of the fifteenth through eighteenth centuries whose adventures fill Ukrainian lore and inspire an enduring Ukrainian spirit of independence and daring.

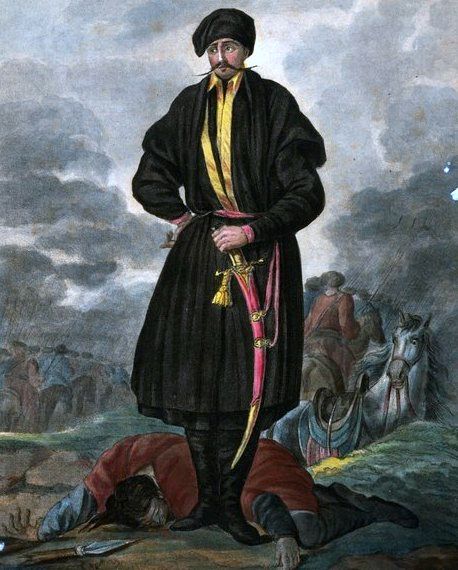

Knights, pirates, samurai, cowboys—different cultures around the world look to different historical figures in their past who embody strength, adventure, and other values central to their cultural identity. For Ukrainians, the Cossacks, or Kozaks, are such figures, emphasized and even romanticized in artistic and historical accounts over the centuries.

The Ukrainian national anthem, whose lyrics were written by Pavlo Chybynsky in 1862, amidst growing nationalism when Ukraine was under the control of the Russian Empire, says: “Soul and body shall we lay down for our freedom / And we will show, brothers, that we are of the Cossack nation!” The reference to the Cossacks in the anthem still sung today solidifies the significance of these people in Ukraine’s ongoing self-identity and fight to maintain sovereignty.

The term Cossack comes from a Turkish word meaning “free man.” Their origins are disputed, but most scholars agree that they were a multiethnic group formed from tribes living in the area, as well as from burghers, peasants, and escaped serfs who fled to the steppe. Ukraine’s Cossacks are first mentioned in sources of the late fifteenth century, and their rights as an independent community were abolished by the Russian Empire in the late eighteenth century.

The enduring mythology of the Cossacks paints them as semi-nomadic, semi-militarized bandits. They lived around the lower bends of the Dnieper River, near Ukraine’s most fertile agricultural lands. Their history and identity were influenced by their geography, the politics and social forces of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth that controlled their lands, and their own self-fashioning.

Other Cossack groups lived across today’s Eurasia, such as the Don Cossacks in Russia, but Ukraine’s Zaporozhian Cossacks uniquely asserted a nascent Ukrainian nationalism. If in the fifteenth century they were primarily rogue bandits, by the seventeenth century they were beginning to symbolize a Ukrainian secessionist movement against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. By shaping the identity of the Ukrainian region, the Cossacks lay the groundwork for it to become the independent nation it is today.

At the same time, the Cossacks’ predominantly military identity may have limited the scope of the political and social reform they could achieve. Although they exercised democratic self-rule, much of their attention went to defending their fertile and resource-rich land against invasion.

Among the most famous Cossacks whose adventures fill Ukrainian lore are Bohdan Khmelnytsky (c. 1595-1657) and Ivan Mazepa (1639-1709). Both were Cossack leaders, or hetmans, whose decisions changed the course of the Cossacks’ future.

Khmelnytsky led an uprising against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1648–54 to form an independent Ukrainian state. However, looking around for allies, Khmelnytsky signed the Treaty of Pereyaslav with Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich of Russia in 1654, which placed the Cossacks under Russian protection. The agreement was intended to preserve Cossack independence, but instead it initiated a long history of Russian domination in the region.

Russia asserted increasing control over the Cossacks, taking advantage of their military might and sending their forces to fight far from home. Yet Tsar Peter I (r. 1682-1725) refused to protect Ukraine from a threat from Sweden, leading hetman Ivan Mazepa to defect from Peter’s army in the Battle of Poltava (1709) to side with the invaders, who promised Ukrainian independence.

The Russian army responded to this betrayal by massacring the Cossacks, defeating Sweden, and only amplifying Russian dominance over Ukraine. Mazepa remains reviled in Russian history, while Ukrainians have remembered him as a hero.

A romantic mythology shaped the Cossacks’ identity in their own day just as it has shaped their memory in the centuries since. Taras Shevchenko, beloved poet of Ukraine, memorializes the Cossacks in his book The Kobzar: “Formerly the Kozaks cherished / Freedom and great glory. / Glory lives but bitter slavery / Freedom has devoured. / Formerly they knew to govern. / Nevermore we’ll do it, / But that former Kozak glory / We remember always” (“The Night of Taras,” translated by Clarence A. Manning).

The Cossacks remain symbols of Ukraine’s ongoing fight for sovereignty, as well as their military might that is not to be underestimated.

![]()

Suggested Reading:

Linda Gordon, Cossack Rebellions: Social Turmoil in the Sixteenth-Century Ukraine (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1983).

Paul Robert Magocsi, Ukraine: An Illustrated History (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2007).

Serhii Plokhy, The Cossacks and Religion in Early Modern Ukraine (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001).