Vladimir Putin’s case for war in Ukraine is simple but flawed. In his view there is no such thing as real Ukrainians. Instead, there were simply “the people living in the south-west of what has historically been Russian land [who] have called themselves Russian.”

In his eyes, there is also no legitimate Ukrainian state. That state was “entirely created” by the Bolsheviks after the communist seizure of power in 1917 as part of Lenin’s strategy to “appease the nationalists.” According to Putin, the United States effectively took control of the Ukrainian government and economy after 1991, to the detriment of regional security and the well-being of the people.

Putin paid special attention to the period of World War I and the Russian Revolution when making his historical case for Russia’s invasion.

The Russian President is quite correct that the decade of war and revolution between 1914 and 1924 is critical for understanding both Russian and Ukrainian statehood up to the present day. However, he is entirely wrong that the Bolsheviks created a Ukrainian people and Ukrainian state out of thin air.

Well before Lenin and Stalin took power in November 1917, World War I had crippled the tsarist imperial state. The borderlands (including Ukraine) became arenas of radical nationalization and social collapse.

In March 1917, activists in Kyiv convened a parliament (Rada) as a first step toward greater Ukrainian self-determination. Whether this would eventually take the form of local autonomy within a multiethnic federation or as an independent state, no one really knew. Ukrainian politicians at first acted cautiously, swearing allegiance to the Revolution.

As the summer of 1917 continued, however, a shared future with Russia became less and less attractive. Imperialist attitudes from Russian politicians alienated even those sympathetic to other revolutionary goals, and the collapsing war effort led to anarchy across Ukraine. By the time of nation-wide elections in November, politicians promising to promote Ukrainian interests won by huge majorities.

The Bolshevik seizure of power in the Russian capitals was the final straw, and in January 1918 the Rada declared Ukraine independent. All of this occurred before Putin’s flawed historical analysis even begins.

Far from being the creators of the Ukrainian state, Lenin and Stalin throttled the first modern Ukrainian state in its cradle. Just weeks after Ukraine declared independence, the Red Army seized Kyiv. Ukrainian politicians turned to Germany for help, but assistance came with significant strings attached.

Within months, the revolutionary Ukrainian leadership had been replaced by a Hetman of Berlin’s choosing. The ensuing civil war saw many parties controlling parts of Ukraine, but ultimately the Bolsheviks won. Their victory meant that Ukraine would be part of the Soviet Union until 1991.

The period of war and revolution not only shows us that Putin gets his history backwards, but also that there are other patterns and dynamics that may be relevant during the current conflict.

First, we can see that both in 1917 and today, the biggest “national” problem in the region is Russian nationalism. Ukrainian territories were a particular crucible for Russian nationalist thinkers in the waning days of the empire. Right-wing, proto-fascist movements supported by the Russian government aimed their attention at Ukraine, sponsoring pogroms and violently repressing any nationalist sentiment other than Russian.

This refusal to recognize the reality of an emerging Ukrainian identity was shared not just by right-wing zealots, but also by Russians on the center and the left, who could not imagine a Russia without Ukrainian territories.

Left-wing Russians quickly turned their cognitive dissonance into accusations that all Ukrainian nationalists were right-wing. This was not true—not even close—but it became a bit of a self-fulfilling prophecy. Socialist Ukrainians who fought with the Bolsheviks would soon be savagely repressed. Those who escaped into emigration often turned even further to the right.

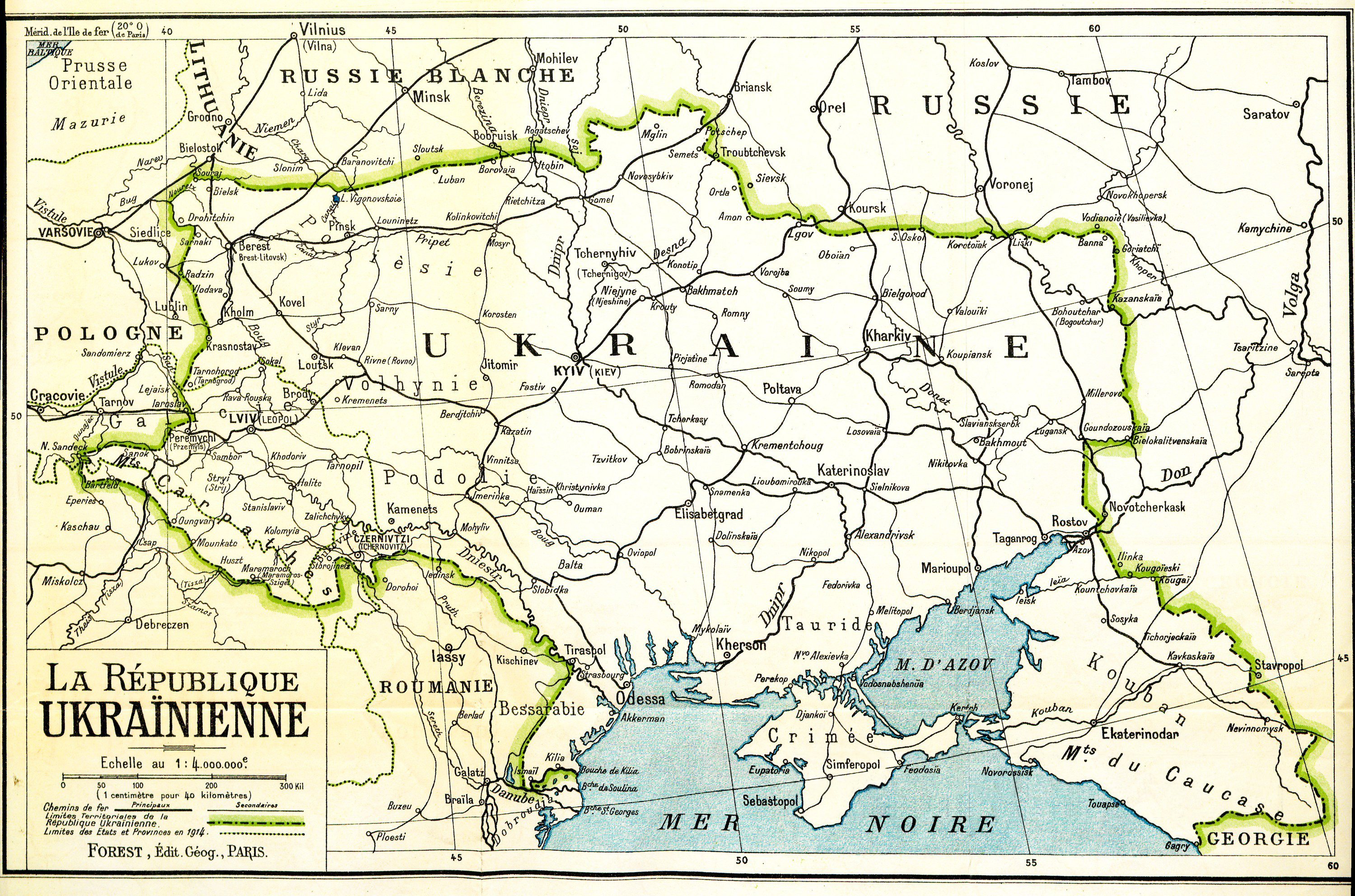

The second lesson from the years of war and revolution is that Ukraine is important strategically and economically for Europe. The strategic value is evident just by looking at a map, but it becomes even more obvious when considering the course of European conflicts over the past two hundred years.

During World War I, the fighting in Ukraine was critically decisive. Ukraine’s role as a grain producer was also of strategic importance in the Great War of blockades. Germany’s main interest in involving itself in Ukrainian politics was to acquire that grain to feed its hungry citizens.

Finally, the German intervention in 1918 reminds us that Great Powers are always important actors in periods of decolonization and nation-building. Ukraine attracted the attention of all the Great Powers during World War I. When Bolshevik aggression threatened Ukrainian independence, the Rada turned to those Great Powers for alliance and support.

Given the economic and strategic importance of Ukraine for Europe, it is inevitable that any war on Ukrainian territory will attract the interest of those powers, in particular when Ukrainian politicians invite involvement.

In the period of war and revolution, Ukraine was seen as a sovereign nation by its own residents but as an integral part of Russia by most Russian politicians.

But Ukraine is not simply important to Ukrainians and Russians. It is a strategically and economically valuable linchpin of Europe as a whole. There can be no local war in Ukraine, and this is as true today as it was a century ago. All the previous modern wars in Ukraine had global dimensions. So too does the one in 2022.

![]()

Learn More:

Paul Browder and Alexander F. Kerensky eds., The Russian Provisional Government, 1917: Documents. 3 vols. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1961.

Oleh S. Fedyshyn, Germany’s Drive to the East and the Ukrainian Revolution, 1917-1918. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1971.

Dominic Lieven, The End of Tsarist Russia: The March to World War I and Revolution. New York: Viking, 2015.

Mark von Hagen, War in a European Borderland: Occupations and Occupation Plans in Galicia and Ukraine, 1914-1918. Seattle, University of Washington Press, 2007.

Serhy Yekelchyk, Ukraine: Birth of a Modern Nation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.