One hundred years ago, in wartime Petrograd, Russian radicals known as the Bolsheviks carried out “the Great October Socialist Revolution.” On the night of October 24, 1917, Bolshevik Red Guards began to take control of key points in the Russian capital—railway stations, telegraph offices, and government buildings. By the following evening, they controlled the entire city with the exception of the Winter Palace, the seat of the Provisional Government.

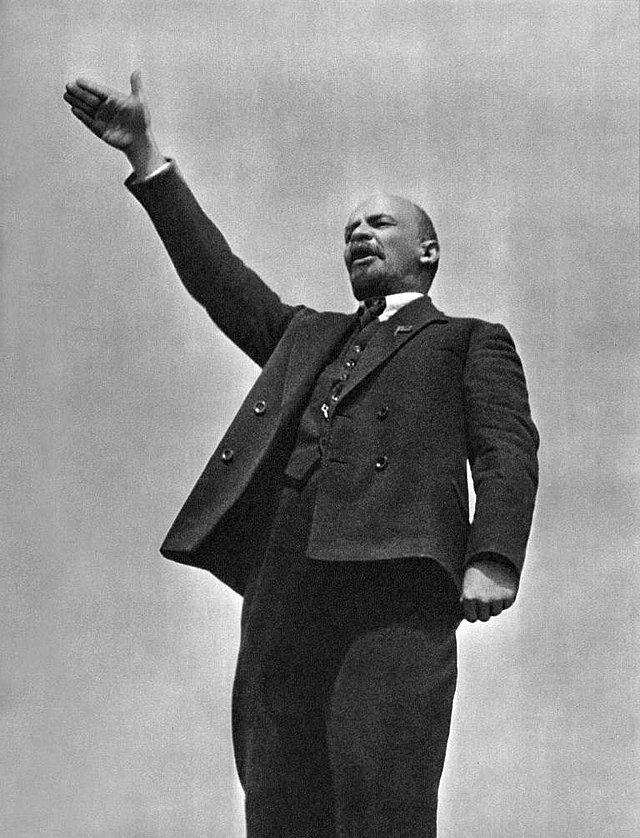

Vladimir Lenin giving a speech in Moscow.

This government had ruled Russia since Tsar Nicholas II’s abdication the preceding February, but it had lost almost all support as Russia’s horrific World War I casualties continued to mount. In fact, at this crucial moment Provisional Government ministers could find almost no one willing to defend them. That night, Bolshevik Red Guards broke into the palace and arrested the ministers, bringing the Provisional Government to an end.

Former Tsar Nicholas II in Tsarskoye Selo following his abdication in March 1917, (left) and Bolshevik forces marching on Red Square, 1917 (right).

The “storming of the Winter Palace” has gone down in history as the climactic moment of the October Revolution. But overthrowing the existing government turned out to be the easy part. Over the next three years, the Bolsheviks (soon renamed Communists) would have to win power in a bloody civil war and reestablish order in a country that had descended into anarchy.

For both opponents and supporters, the October Revolution represented the advent of socialism. Those on the political right saw socialism as scourge that entailed the violent expropriation of private property and the trampling of individual liberties. And throughout the twentieth century, Soviet socialism continued to be seen as an existential threat to liberal democracy and capitalism.

But many on the left welcomed the Revolution as the start of a new era, with harmony and equality for all people. Particularly given the senseless slaughter of millions of soldiers during the First World War, the October Revolution seemed to offer an alternative—a government ruled in the interests of the common people that would ultimately produce a communist utopia.

"Sacrifice to the International," an anti-Bolshevik propaganda poster, in which Lenin is depicted in a red robe, aiding other Bolsheviks in sacrificing Russia to a statue of Marx, 1919 (left), and "Glory to victorious Red Army soldier!" by Dmitrii Stakhievich Moor, 1920 (right). (New York Public Library Digital Collections)

One hundred years later, the October Revolution still stands as a seminal event in world history. But no longer can it be seen in Marxist terms as part of the inevitable progression from feudalism to capitalism to socialism to communism. Instead, the Revolution today is often viewed as a cautionary tale about the dangers of socialist ideology.

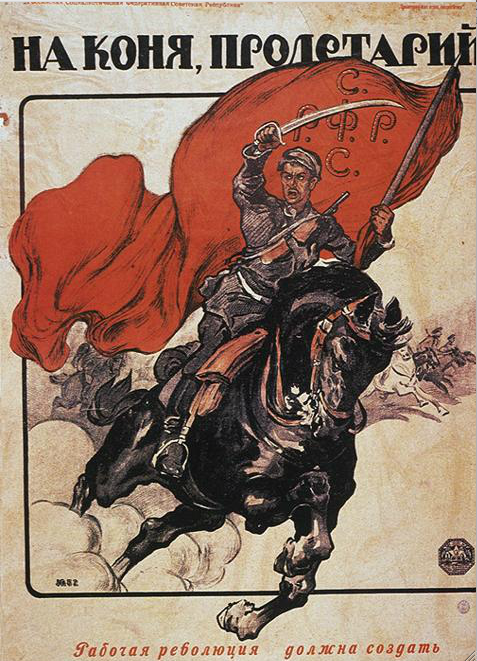

Russian Civil War era poster by Alexander Apsit reading "To Horse, Proletarian!," 1918.

According to this thinking, the socialist ideas pursued by Communist Party leaders led to the crimes of Stalinism, which produced neither equality nor harmony but left millions of people dead. With the collapse of the Communist regime in 1991, the anniversary of the October Revolution is no longer celebrated in Russia. Many people regard the entire Soviet epoch as a tragedy, the result of socialist thought put into practice.

Soviet poster depicting Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Stalin, 1933.

Was the Soviet regime really a product of socialist ideology? In some ways it was. Vladimir Lenin and other Communist Party leaders were committed to Marxism, one branch of socialism, and they understood the world in terms of class categories. Their policies included violent expropriation of private property and class warfare.

But Marxist thought provided no blueprint for constructing a socialist state. Most of Karl Marx’s writings had been a critique of capitalism, and he described the socialist future only in vague terms. Nowhere did he outline what became the fundamental institutions of the Soviet state—a fully state-run, planned economy; government bureaucracies for censorship and propaganda; the secret police and its system of surveillance; and the network of forced labor camps known as the Gulag. These institutions were instead based upon wartime practices of the First World War and Russian Civil War.

Red Army soldiers before being sent to the Civil War, 1919.

Combatant countries throughout Europe during the First World War had increased state control over their economies, through price controls, rationing, production quotas, and grain requisitioning. They had utilized censorship and propaganda to maintain soldiers’ and citizens’ morale. The governments of all combatant countries also had engaged in widespread surveillance of their citizens. And in addition, they had created concentration camps to intern “enemy aliens” and, in some cases, their own subjects during the war.

After the October Revolution, Communist leaders used all of these methods to fight the Civil War and establish control over the far-flung Russian empire. Unlike in other countries, where governments stepped back from total war practices after the war ended, the Soviet state was formed in conditions of anarchy and civil war, and these practices became institutionalized as permanent features of governance.

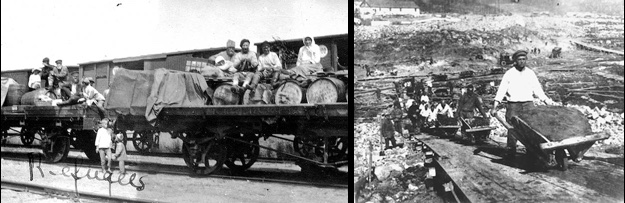

Refugees fleeing the Civil War (left), and prisoners working at Belbaltlag, a camp for building the White Sea-Baltic Sea Canal (from the 1932 documentary film Baltic to White Sea Water Way, Central Russian Film and Photo Archive) (right).

The October Revolution, then, produced a highly militarized version of socialism, one in which state control and violence became fundamental components. While Marxist ideas and categories shaped Communist policies, the Soviet state cannot be divorced from the historical conjuncture in which it arose—a moment of total war.

In the 1930s, Soviet state violence became even more pervasive, as Joseph Stalin sought to prepare the Soviet Union for the next war. Wartime practices such as grain requisitions and deportations were used to collectivize agriculture. The Soviet planned economy, essentially a wartime economy, marshaled labor and raw materials for enormous industrial projects that modernized the country. During the Second World War, the Stalinist leadership relied on these same institutions of state violence and control to mobilize vast human and material resources for the war effort.

Both Stalinist industrialization and victory over Nazi Germany, however, were obtained at tremendous cost. During the 1930s, several million Soviet citizens died due to famines, deportations, and executions. An estimated 27 million more died during the Second World War. Even after the war, the Stalinist government continued large-scale deportations and incarcerations of its own citizens.

Children dig up potatoes on a collective farm near Udachne villiage, Donec'k oblast, 1933 (left), and collective farmers from the Moscow suburbs handing over tanks manufactured on their money to Soviet servicemen, December 1942 (right).

USSR Day of the October Revolution, 1938.

"Everything for the Front. Everything for Victory." USSR propaganda poster from World War II, 1941 (left); and ‘"Stalin’s spirit makes our army and country strong and solid," Viktor Deni & Nikolai Dolgorukov, 1939 (right).

In the end, the Soviet state’s legacy of coercion and bloodshed proved to be its undoing. When Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev lifted censorship in the 1980s, discussion of the system’s violent past quickly undercut its legitimacy. By 1991, Communist rule had ended and the Soviet Union disintegrated.

The October Revolution shaped the twentieth-century world arguably more than any other single event. It brought to power a new regime, one that ruled in the name of the working class and that established a non-capitalist, state-run economy. This regime carried out a brutal industrialization drive that enabled the Soviet Union to play the leading role in defeating Nazi Germany and winning World War II. And the existence of the Soviet Union also led to the Cold War, the superpower confrontation with the United States that dominated world affairs for the entire postwar era.

The October Revolution did not, however, mark a new stage in history or humankind’s inevitable progression toward a communist utopia. And the Soviet system that resulted from it, while socialist in some respects, was characterized by institutions of government control and state violence. A century after the October Revolution, we can see that above all else the Soviet state reflected the era of mass warfare in which it arose.