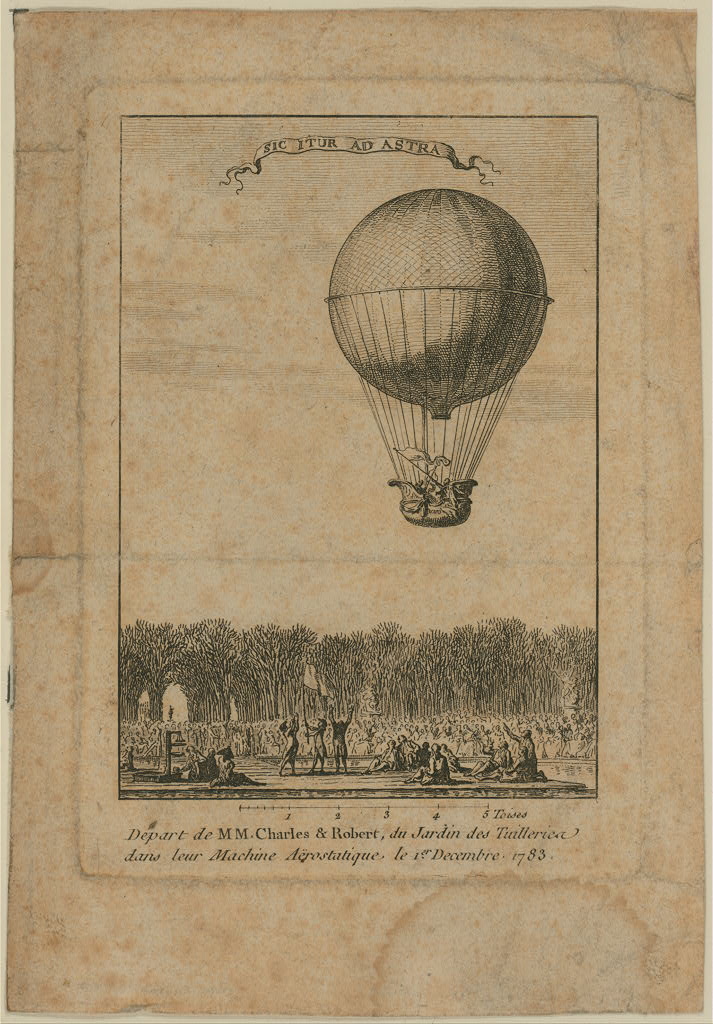

On December 1, 1783, an immense crowd gathered on the grounds of the Tuileries Palace in Paris to witness one of the first manned balloon ascents. The exhibition attracted Parisians from all walks of life, from those who could afford to purchase tickets and experience the flight up-close to those who packed the streets outside the garden walls in hopes to catch a glimpse of the flying machine. Once the balloon rose from its platform, the varied “swarm of people” observed together what Louis-Sebastien Mercier declared “the most astounding achievement the science of physics has yet given to the world.”

As Mi Gyung Kim describes in The Imagined Empire: Balloon Enlightenments in Revolutionary Europe, the balloon became the national artifact of late eighteenth-century France, symbolizing an assortment of often conflicting ideals that existed in the mindsets of its diverse inhabitants. The soaring technical triumph provided a poignant metaphor for both royal legitimacy and unfettered political opportunity, which in turn created differing visions of optimum government.

In this work, Kim reveals the cultural and political agency used in creating modern European nations, particularly France, through the history of early ballooning. Kim argues that the spectacle surrounding demonstrations of science and technology in the age of Enlightenment helped to define the revolutionary public sphere.

Serving as an identifier to different people across the social spectrum, the balloon was a concrete example of abstract values which came to represent France’s transition from the ancien régime to republicanism. For the absolutist state, balloon ascensions became shows of monarchical majesty and authority through elaborate and closely monitored displays (the balloon as a “king-machine”). Yet for the masses, the balloon served as an allusion for rising above absolutist constraints, stimulating patriotic sentiments, and the desire to create a utopian republic (the balloon as a “people-machine”).

Balloons became instrumental in consolidating and mobilizing popular unrest, for unlike many other inventions that were only accessible to the elite, the high-flying balloon was inescapably visible to all classes. For this reason, Kim claims that the discussion surrounding ballooning exposes public perceptions of both the height and decline of French absolutism during its final years.

By reexamining layers of society through the lens of ballooning, Kim aims to incorporate middle and lower classes into the narrative of France’s public sphere, a domain chiefly dominated by the literate, educated elite. Her rich descriptions of newspaper articles, pamphlets, and personal memoirs detailing balloon ascents portray the intricacies of the eighteenth-century scientific field and its reception by potential patrons, reporters, and essayists.

At the same time, her analysis of both individual flights and the overarching concept of human ascent seeks to look beyond the archive in order to reveal the opinions of the mass public. Kim alludes to the public’s mood toward technology and politics through stories of balloonists’ celebrity or infamy, and the seamless way in which she interweaves numerous images into these accounts brings early flight to life.

Kim has undertaken a monumental task in attempting to penetrate the silent mass public, so it is understandable that she occasionally makes conjectures without entrenching them in specific pieces of evidence. It is challenging, however, for readers to follow her train of thought when she does not sequentially explain her reasoning. A large portion of the book recounts notable figures and ascents, but while the anecdotes make for an interesting read, more text could have been devoted to clearly connecting those particulars to the public voice. Kim mentions previous scholarship regarding the cultural and intellectual history of the Enlightenment but does not explicitly tie it into her analysis, making it particularly difficult for readers who do not have a basic historiographical understanding of eighteenth-century French political culture to follow her discussions.

Given that The Imagined Empire largely depicts pre-revolutionary France, it begs the question: how well does ballooning really explain the political atmosphere leading up to the French Revolution?

Kim does not seem to fully provide an answer. She reinforces preexisting arguments about French civil society by applying them to ballooning culture, yet does not make an especially solid case for balloon influence on revolutionary ideology. For example, chapter seven tells of the increasing criticisms of the practicality of balloons in the latter half of the 1780s, stating that its royal and aristocratic patrons became progressively disparaged but without providing a detailed explanation. Here it seems as though Kim assumes the reader has enough background knowledge to discern its relevance without directly stating the correlation between balloon unpopularity and monarchical disapproval. But even with that familiarity, she does not provide new insights regarding the desacralization of the monarchy.

Kim maintains that as an identifier for political culture, the balloon served as both a “king-machine” and “people-machine” that expressed various visions for the French state, yet the evidence presented in The Imagined Empire depicts the balloon as more of an “inventor” or “aeronaut-machine.” Given the nature of the available sources, much of the book focuses on the individual inventors and flyers rather the crowds. A more fleshed out analysis could have better interlaced the populace into the narrative. In spite of this, the book provides an interesting perspective for scholars well acquainted with Enlightenment and Revolutionary political culture who wish to further contemplate the relationship between technology and the public sphere.