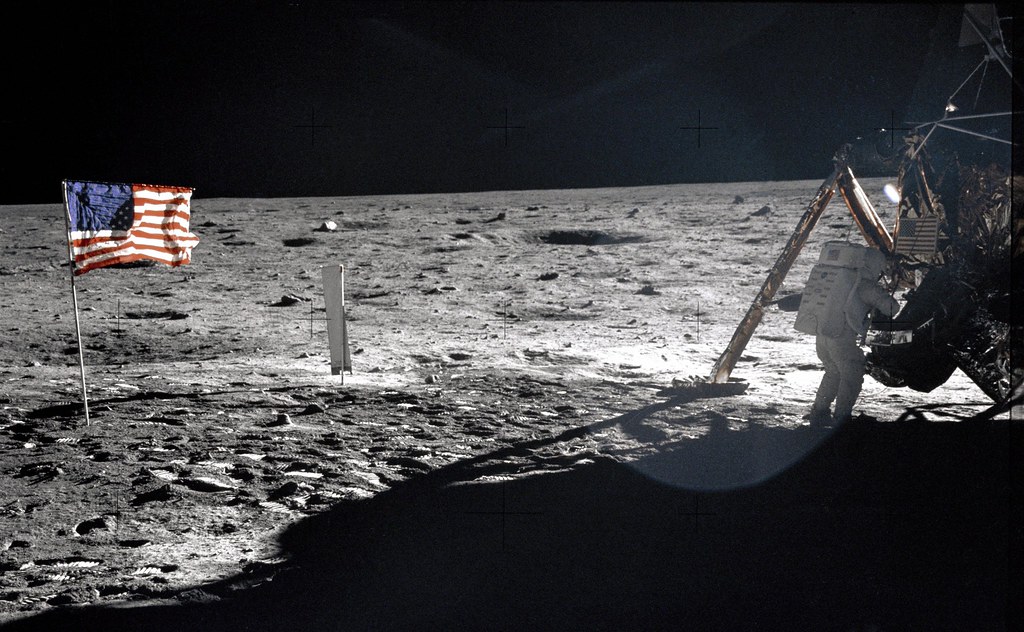

Neil Armstrong stands by the Lunar Module "Eagle" during the first walk on the moon in 1969.

On July 21, 1969, American astronaut Neil Armstrong became the first human being to set foot on an entirely different world. His famous words crackled across 238,900 miles of space and electrified those listening back home on Earth: “That’s one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind.”

That Armstrong chose to highlight the labor of so many others who together made the moon landing possible not only speaks to his singular humility—a trait on full display in the recent documentary Apollo 11. It also reflects the reality that the Apollo 11 moon mission resulted from a monumental deployment of capital, expertise, labor, support, and sacrifice of thousands if not millions of people.

That achievement has since become a benchmark in American culture. The expression “if we can put a man on the moon…” usually precedes a question about why America has not achieved a goal less complicated than traveling to another celestial body. Calls for large-scale efforts, especially from within the federal government, are characterized as “moonshots”—for example, the call by the Obama administration for a “cancer moonshot” that has been revived in the lead-up to the 2020 election.

Nearly every presidential administration since that first small step has also called for new, literal moonshots, perhaps in the hope of matching John F. Kennedy’s success. Even as the goalposts move, to Mars or an asteroid, the idea of taking a next giant leap for humankind on another celestial body remains a perennial desire among American leadership and, increasingly, wealthy private industry leaders.

However, we have yet to return to the moon, and human spaceflight has remained within low Earth orbit ever since the final Apollo mission ended in December 1972.

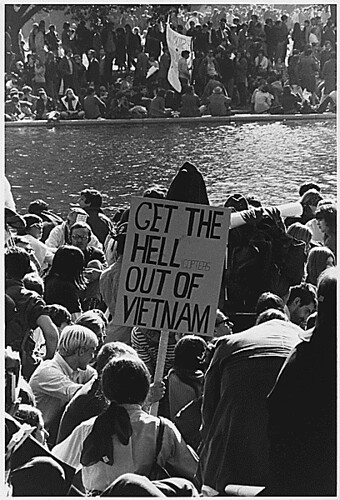

Those who were alive in the summer of 1969 recall where they were and how they felt when humankind became truly cosmopolitan. However, as we mark this anniversary, we should also remember the realities of that turbulent time. We should recognize that the Moon effort came at a cost that may be impossible or at least inadvisable to repeat today.

By the summer of 1969, opposition to the Vietnam War was large and growing, counterculture protests and the Civil Rights movement were transforming American life, and U.S. cities had endured repeated summers of violence.

Although it has become a shining moment in the collective national memory, at the time many Americans opposed public investment in landing two people on a world so far from the problems of everyday people back on earth. Support for the Apollo program waned as soon as it became evident that America would win the race to the Moon, well before Neil Armstrong ever set foot on the surface.

Ultimately, the moonshot was a product of its time, and perhaps most importantly, a product of the Cold War. Its main objective was to demonstrate that, after losing out to the Soviet Union in launching the first satellite into orbit and the first human being into outer space, among other milestones, American ingenuity—and American capitalism—would triumph in the end.

A 1965 Soviet stamp commemorating the first spacewalk conducted by Alexei Leonov.

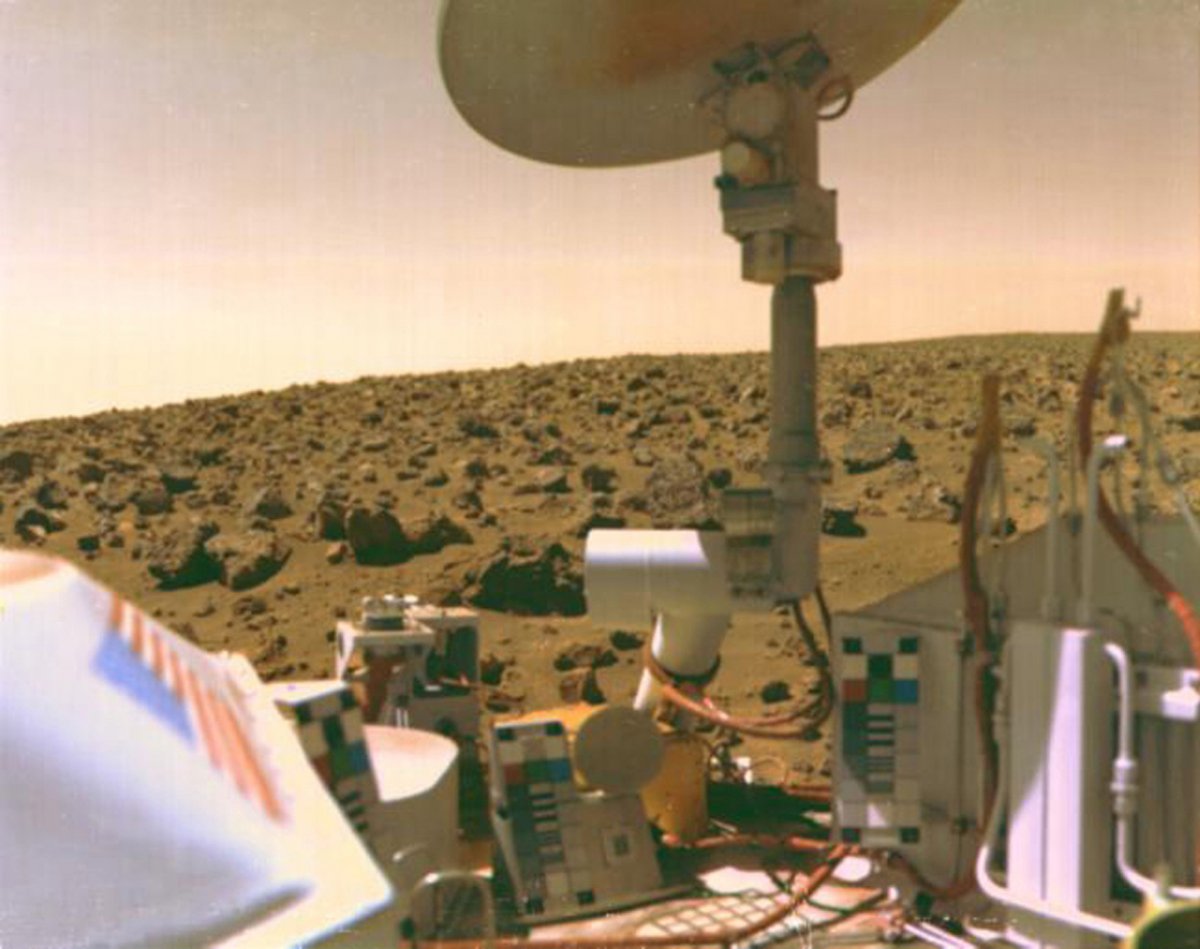

Though the Moon may seem like it was always the goal of the nascent American space program, Vice President Johnson consulted with experts to collect a few potential targets as finish lines to the Space Race. A biologist suggested that the United States dedicate itself to mapping the surface of Mars—a safer bet given the Soviets’ success at building heavy lift rocketry and Americans’ superiority at instrumentation.

The Kennedy administration decided on the Moon, however, reflecting the high value of colonial drama in the (white) American imagination. He repeatedly called space a new frontier.

While humans have not returned to the Moon since 1972, the American space program has achieved extraordinary successes, including landing uncrewed spacecraft on Mars and truly spectacular scientific feats using novel technology. But nothing has captured the imagination quite like the Apollo missions to the Moon. This may explain why American leaders, including Donald Trump, keep calling for a return to the Moon.

If the Apollo program began in the expansive optimism of the 1960s, however, many who want to return to the Moon today are driven by a sense of doom that our planet may not survive humanity. With anthropogenic climate change and rampant pollution affecting the planet on a global scale, setting up house on a new planet seems like it might be a good plan B should Earth not survive the Anthropocene.

As our nearest neighbor, the Moon provides a stepping-stone to Mars—a nearby test site before making the 36 million mile trip to the red planet. Some even think that the Moon might in and of itself be a potentially productive place to build human settlements, or at least a cell phone tower.

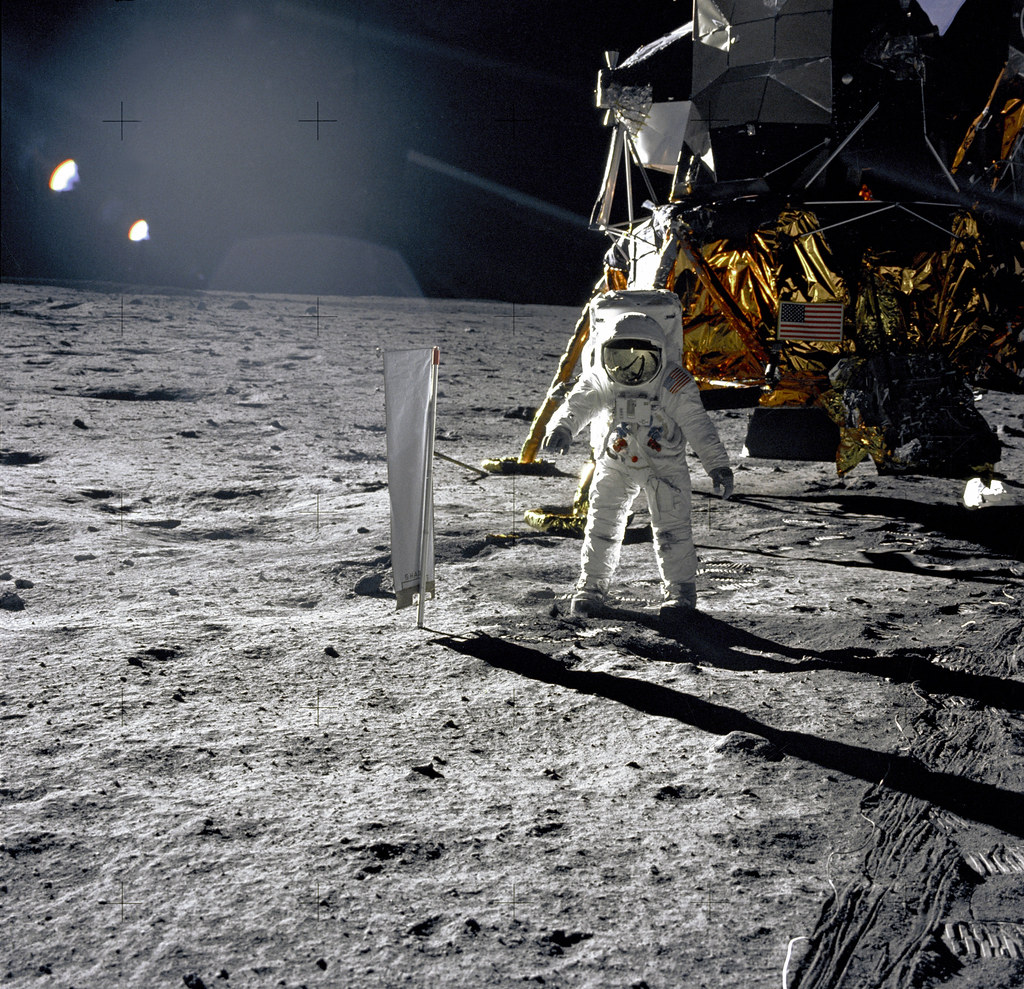

The moments before Armstrong’s one small step perhaps best illustrate reasons for caution.

Upon opening the door of the lunar excursion module, Armstrong took a large white bag full of items the astronauts no longer needed and tossed it to the foot of the spacecraft. The first photograph Armstrong took on the Moon preserves for posterity this first act of taking out the garbage on another world.

While the cosmos may provide a tempting escape route for those who fear the worst for planet Earth, where humans go our garbage goes, too. As difficult as it seems to fix the problems humankind has wrought on our home planet, it may prove just as difficult not to export the same problems somewhere else.