“Keep the government out of my health care.”

If you’ve been privy to any of the discussions on the nature of United States health care in the past couple decades, you have undoubtedly heard this sentence, or some other variation of it. It’s a cry that’s only grown louder with passage of the Affordable Care Act of 2010. With Mother of Invention, Robert I. Field is no stranger to the current debates in health policy. He writes to discredit the notion that the government’s hand is only now sticking its fingers into the healthcare jar.

Field, whose degrees include a JD, a MPH, and a PhD, may be the perfect candidate to settle the current debate on how modern health care developed. His biography hints at the methodical way he dissects the health care system through both a historic and a policy-driven lens. Through this approach, Field promotes a straightforward premise that the United States government and private enterprise collectively worked as equally-involved parents to nurture what is now the largest health care system in the world.

Barack Obama's reaction to the signing of the health care reform bill on March 21, 2010

In a way, Field’s argument—that government and private industry created the health care system we know today—is nothing new. He explains that the health care industry developed much like the railroads, the highway system, the internet, and even the home-building industry. Thus, health care belongs on this list of governmentally subsidized “private” industries.

To him, the “free market” functions as an idealized system of unfettered exchanges between buyers and sellers. There’s no room for the government in this faulty formulation, which he reveals is simply silly since the government has been involved in health care all along. By focusing on the pharmaceutical industry, the hospital industry, the medical profession, and private health insurance, Field illustrates government’s fundamental role in each. Thus, rallying behind a pure “free market” ideology in its purest sense is a historical and political contrariety.

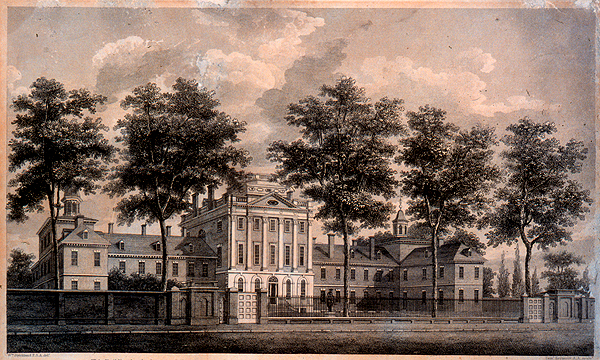

The first hospital in the United States was the brainchild of Benjamin Franklin and a friend Dr. Thomas Bond (among other collaborators), who in 1751 founded the Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia. It replaced the religious almshouses for the poor and sick. Direct government funding of such hospitals quickly followed.

Architect William Strickland's sketch of the first Pennsylvania Hospital

Moreover, since the earliest days of the republic, the state has supported the medical care of military personnel. A year before the nation’s founding in 1775 —when the country geared up for the approaching Revolutionary War—the first wave of government subsidizations backed private health care. By 1798, Congress had authorized the creation of a Marine Hospital Service to build hospitals to treat ill sailors.

The rise of the professional doctor followed this same state-backed trajectory. Faced with a shortage of doctors, the federal government decided to build more vocational schools for the new profession. It was only then, with direct government involvement, that this coveted profession thrived and grew.

But healing also happens in the home. Every American who has taken a prescription drug in the past 50 years is ingesting the product of a public-private collaboration. Field’s chapter on pharmaceutical drugs is perhaps his most convincing. Taxol, in particular, the best-selling cancer drug in history, is the product of a long back-and-forth between the public and private sectors. The discovery of this drug’s base came from the research of a botanist employed by the United States Department of Agriculture, intent on exploring the healing properties of yew bark (pictured above). Though drugs are sold in what is usually thought of as a “free market,” this occurs only as a result of the government’s direct involvement in the production and regulation of pharmaceuticals.

Alas, the reader might have spied a large hole in the health system up to this point: to pay for everything from hospital visits to prescriptions, one needs health insurance. Of the country’s entire investment in health care, around 33 percent was financed through private health insurance in 2010, more than doubling the average of 15 percent in the rest of the world. Field points out that this “private” health insurance system is only made possible by various government policies of the twentieth century.

In one of the final chapters, the author outlines how the state subsidized what is now a multi-billion dollar private health insurance industry. From workplace programs to coverage afforded by Medicare and Medicaid, the government created the system it is now bound to and restricted by. This has continued with the crafting of the ACA, which only expanded the government’s reliance on private insurance to cover the uninsured.

Field does not shy away from his central metaphor—that of a doting mother preparing chicken soup for a stuffy-nosed child. With Mother of Invention, he certainly proves his point: even if the government wasn’t serving the soup, it usually created the can. It had a key role in the development of this system from the earliest days of the nation. The government was there all along, though Field may do better to address the negative effects of its influence as well as the positive contributions lest he be criticized for leftist bias.

Medicaid and Medicare spending as part of total U.S. healthcare spending

Still, perhaps Field’s strongest argument that translates to the future of American health care comes in his final chapter. “Health care cannot function,” he declares, “without a solid infrastructure of regulation and financing that only it [the government] can provide.”

In this sense, government involvement remains a necessary component for healthcare to advance. In the author’s estimation, the government’s hand will not be going anywhere anytime soon, and moreover, we should hope it doesn’t if we want to keep the behemoth that is American health care running.