The Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified on August 18, 1920. The amendment states: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

Although the amendment prohibited the denial of women’s voting rights based on their “sex,” not all women could cast a ballot equally after its ratification. Neither the path to the amendment nor the journey after it were straightforward.

Some property-owning women had the opportunity to vote before the women’s suffrage movement gained traction. In 1776, New Jersey’s state constitution declared that “all inhabitants” who were “worth fifty pounds” and met the residency and age requirements could vote.

In statutes passed in 1790 and 1797, New Jersey legislators clarified the description of eligible voters by including the words “he or she.” Propertied women continued to vote in New Jersey until 1807 when the state’s legislators limited voting to white, male citizens who met the qualifications laid out in the new law.

The birth of a full-fledged suffrage movement awaited the development of new forms of grass-roots political activism and broadening conceptions of human rights. Both of which congealed in the burgeoning abolitionist movement in the 1830s. Anti-slavery petition drives and abolitionist stump speaking were lessons in political mobilization for women, such as Maria Stewart and Sarah and Angelina Grimké.

So too, arguments about fundamental human rights made on behalf of slaves applied to women as well. Thus during the late 1840s and the 1850s, women participated in women’s rights conventions throughout the country, and suffrage emerged as a centerpiece in the women’s rights movement.

After the Civil War, the Fifteenth Amendment, passed by Congress in 1869 and ratified in 1870, prohibited the denial or abridgement of voting rights based on “race, color, or previous condition of servitude,” but not “sex.” The Amendment exacerbated tensions already present between those advocating for African American civil rights and those fighting for women’s suffrage.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony sought to prioritize the rights of native-born, white, middle-class women over immigrants, poor women, and women of color. They refused to support the Fifteenth Amendment because it did not include women’s suffrage, and in 1869 they formed the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) to advocate for a federal women’s suffrage amendment.

Months later, Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell formed a rival group, the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), which supported the Fifteenth Amendment and concentrated on state campaigns for women’s voting rights. The two organizations remained separate until 1890, when they merged to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).

Progress towards women’s suffrage was uneven, dependent on both geography and race. The first federal women’s suffrage amendment was presented in Congress in 1878, but it fell considerably short of the necessary votes in the Senate in 1887.

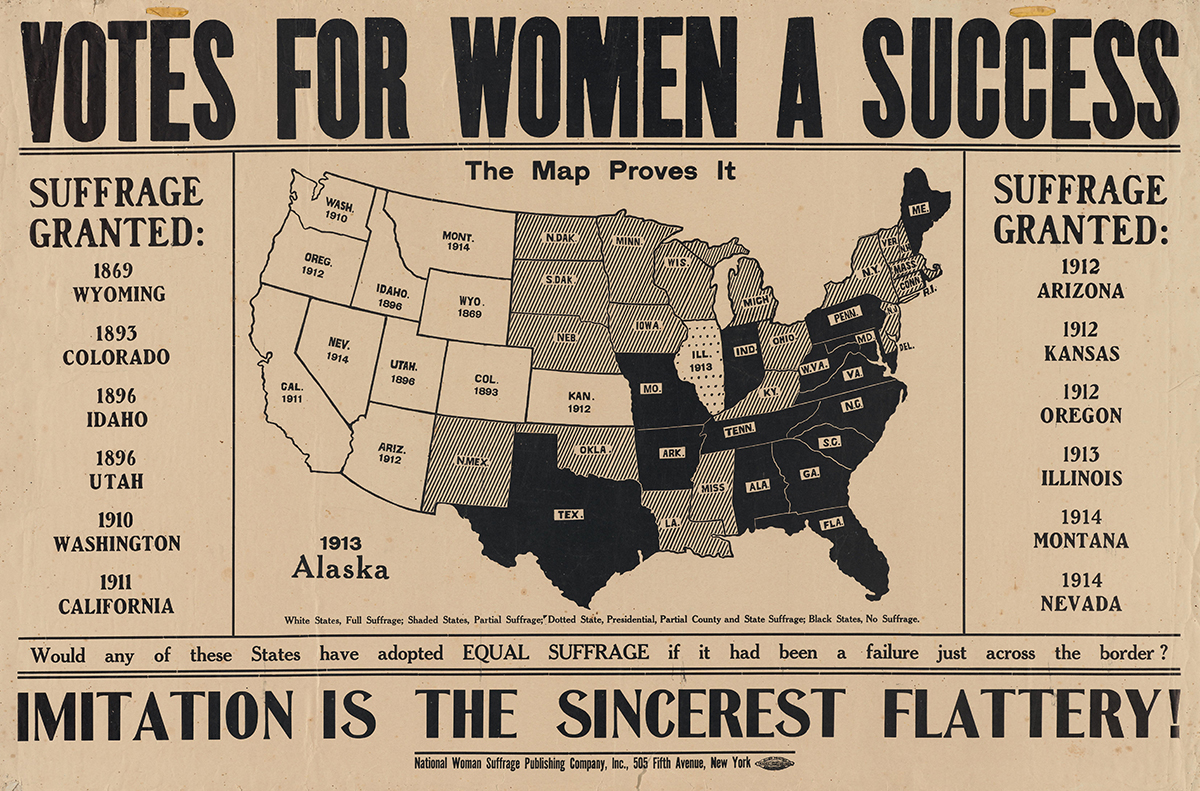

A 1914 map, showing the progression of women's suffrage in various states.

Although the path to a federal amendment appeared bleak, women in western states made suffrage gains. Women in Wyoming Territory, for example, voted in local elections beginning in 1869, and Wyoming entered the union in 1890 as the first state with female suffrage. Several more Western states followed suit, including Colorado (1893), Washington (1910), and California (1911). In each of these states, however, white women had greater access to the ballot box compared to women of color.

The continued disenfranchisement of women of color led activists like Mary Church Terrell to insist that NAWSA fight for the rights of African American women.

At the 1913 Suffrage March in Washington D.C., Ida B. Wells marched with the Illinois delegation, refusing to follow the request from organizers that African American suffragists march in a separate contingent at the back.

Ida B. Wells marching in the 1913 Suffrage March.

The same year, Wells established the Alpha Suffrage Club in Chicago, an organization that later registered thousands of African American women to vote. These new voters played a huge role in electing Oscar De Priest as Chicago’s first African American alderman.

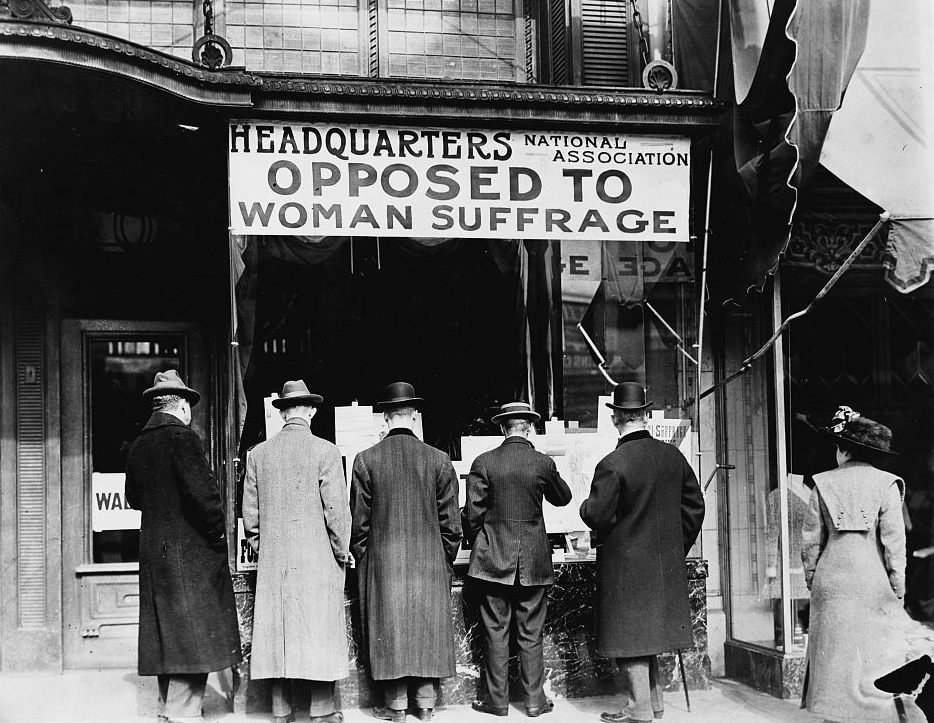

Not all women, however, pushed for the right to vote. Indeed, many women joined the anti-suffrage movement. Often some of the most elite white women in society, the female leaders of the anti-suffrage movement wanted to protect interests that stemmed from the intersections of their race, class, and gender. They claimed that voting would taint the feminine influence they derived from the cultural construct of “separate spheres” for men and women.

The headquarters of the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage in 1911.

Anti-suffrage state organizations sprouted up at the turn of the twentieth century. In 1911, anti-suffragists formed the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (NAOWS), with its national headquarters in New York City. In 1915, female anti-suffragists helped defeat a women’s suffrage referendum in New York.

The tide soon turned against the anti-suffragists, however. The 1910s witnessed a revived push for a federal amendment, as American women adopted the more confrontational tactics used by suffragists in other parts of the world.

Suffragists picketing in front of the White House, February 1917.

Starting in January 1917, Alice Paul and other members of the National Woman’s Party began picketing the White House, applying pressure on President Woodrow Wilson to publicly support an amendment.

That same year, New York finally passed its state suffrage amendment, providing a critical victory for the suffragists in what was then the nation's most populous state and signaling that public opinion was now firmly behind women's suffrage. In 1918, President Wilson, facing a difficult midterm election, announced his support for a federal amendment.

Buoyed by this momentum, both houses of Congress passed the Amendment in 1919 and submitted it to the states for ratification. By the summer of 1920, thirty-five states had ratified the amendment, one short of the thirty-six necessary to amend the Constitution. A fierce battle between pro- and anti-suffrage forces erupted in Tennessee, but the suffragists prevailed on August 18, 1920, when Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify.

The passage of the Nineteenth Amendment did not give all women access to the ballot box.

U.S.-born women who married non-citizen men automatically lost their citizenship, and their voting eligibility along with it. After pressure from suffragists, Congress passed the Cable Act of 1922, which restored citizenship (and thus voting rights) to women who had married non-citizen husbands. The law, however, did not apply to women married to “aliens ineligible for citizenship,” a group that largely included Asian immigrant men.

The Nineteenth Amendment also did not apply to women in U.S. territories. In Puerto Rico, for example, the territorial legislature granted the right to vote to literate women only in 1929; all other women had to wait another six years to gain suffrage.

In the South, meanwhile, poll taxes, residency requirements, literacy tests, and intimidation that had already been in place for years restricted African American women’s ability to vote. Mexican American women faced similar hurdles.

Although an act by Congress in 1924 recognized all Native Americans born in the U.S. as citizens, Native American women (as well as Native American men) continued to encounter obstacles to suffrage for decades. Also, immigration and naturalization restrictions ultimately meant that many women of Asian descent could not vote until the mid-twentieth century.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965, along with subsequent extensions of the legislation, enabled access to the ballot box that the Fifteenth and Nineteenth Amendments failed to provide.

A century after ratification, women are running for political office at higher numbers than ever before. The midterm elections of 2018 ushered in a record number of women in Congress, yet women still fill less than a quarter of the seats of the 116th Congress. Additionally, the United States has yet to elect a woman to serve as President, although several have run for the highest office in the land.

Ultimately, the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment was not a laudatory ending point, nor or even a beginning point, in the history of women’s political engagement. Years before ratification, women lobbied and organized; some even had the chance to vote and did so. As a century after ratification has shown, access to the ballot box has been uneven, and there is still a long way to go in terms of representation in political office.