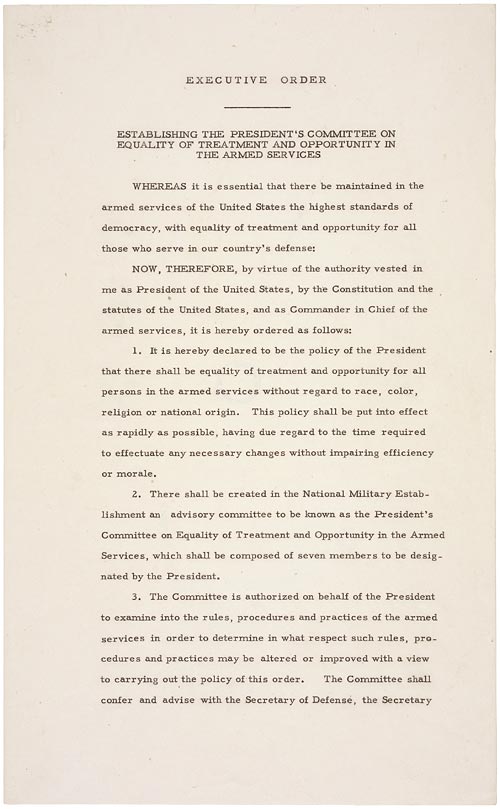

On July 26, 1948, President Harry S. Truman ordered the desegregation of the United States Military. Executive Order 9981 required “equal treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion or national origin.” And the policy was to be “put into effect as rapidly as possible” but with careful consideration to not affect military efficiency or morale.

Issued alongside Executive Order 9980, which prohibited discrimination in federal agencies, Executive Order 9981 was a defining moment of Truman’s Presidency but also a landmark victory for African American activists and Civil Rights leaders who had long advocated for the end of segregation in the military.

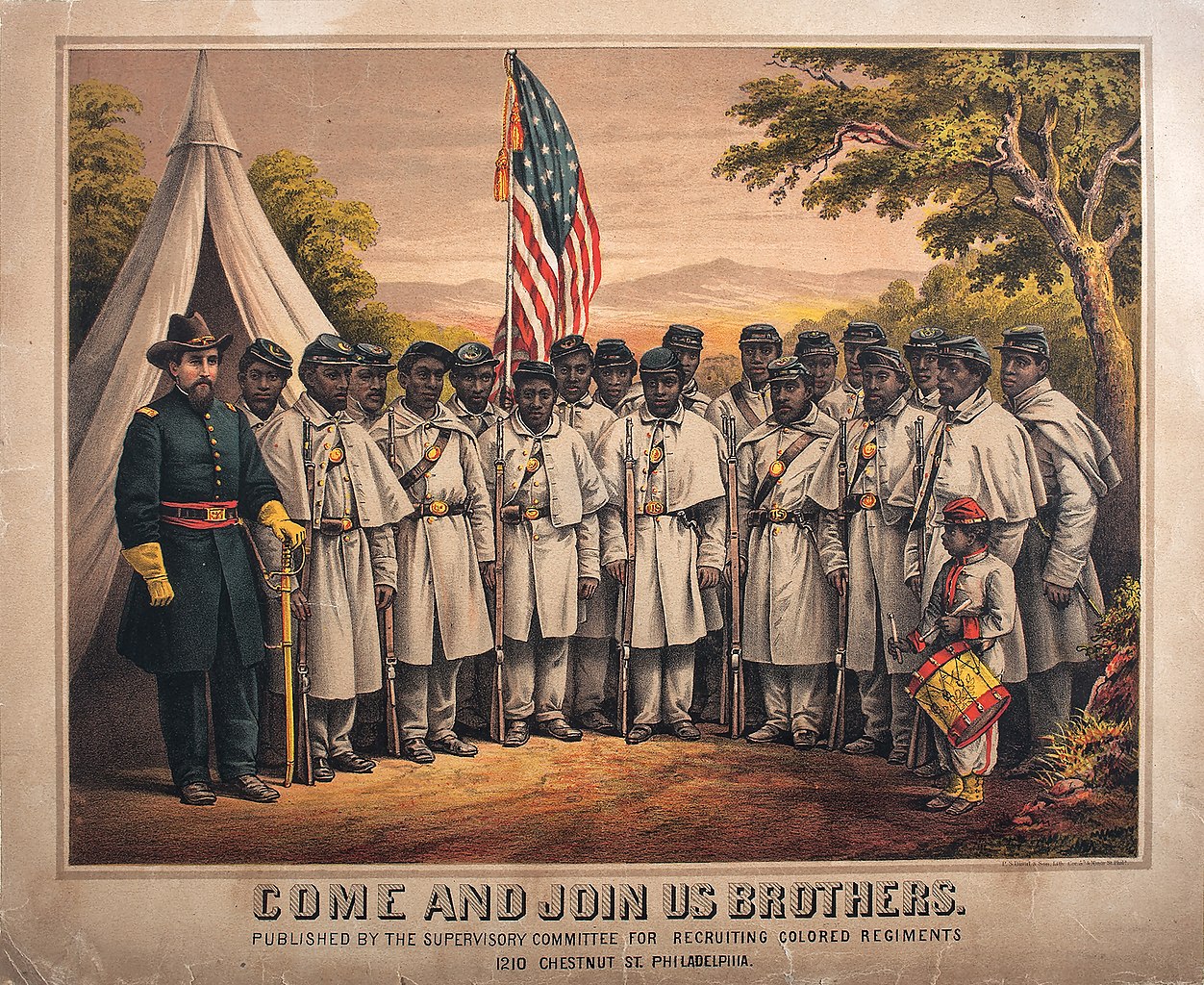

African Americans have a long history of military service. Black men served in colonial militias during the French and Indian War and the American Revolution. Over a hundred thousand Black men fought to free themselves and their brethren during the American Civil War. After the Civil War, the Buffalo Soldiers saw storied service in the American West. Racism and segregation, however, were defining features of Black soldiers’ military service.

During these conflicts, Black men served in segregated units under white officers. This dynamic greatly limited Black soldiers’ opportunities for advancement and emphasized their status as lesser citizens and lesser men. While African American soldiers and communities protested these conditions, the small size of the U.S. military made calls for integration easy for white authorities to ignore.

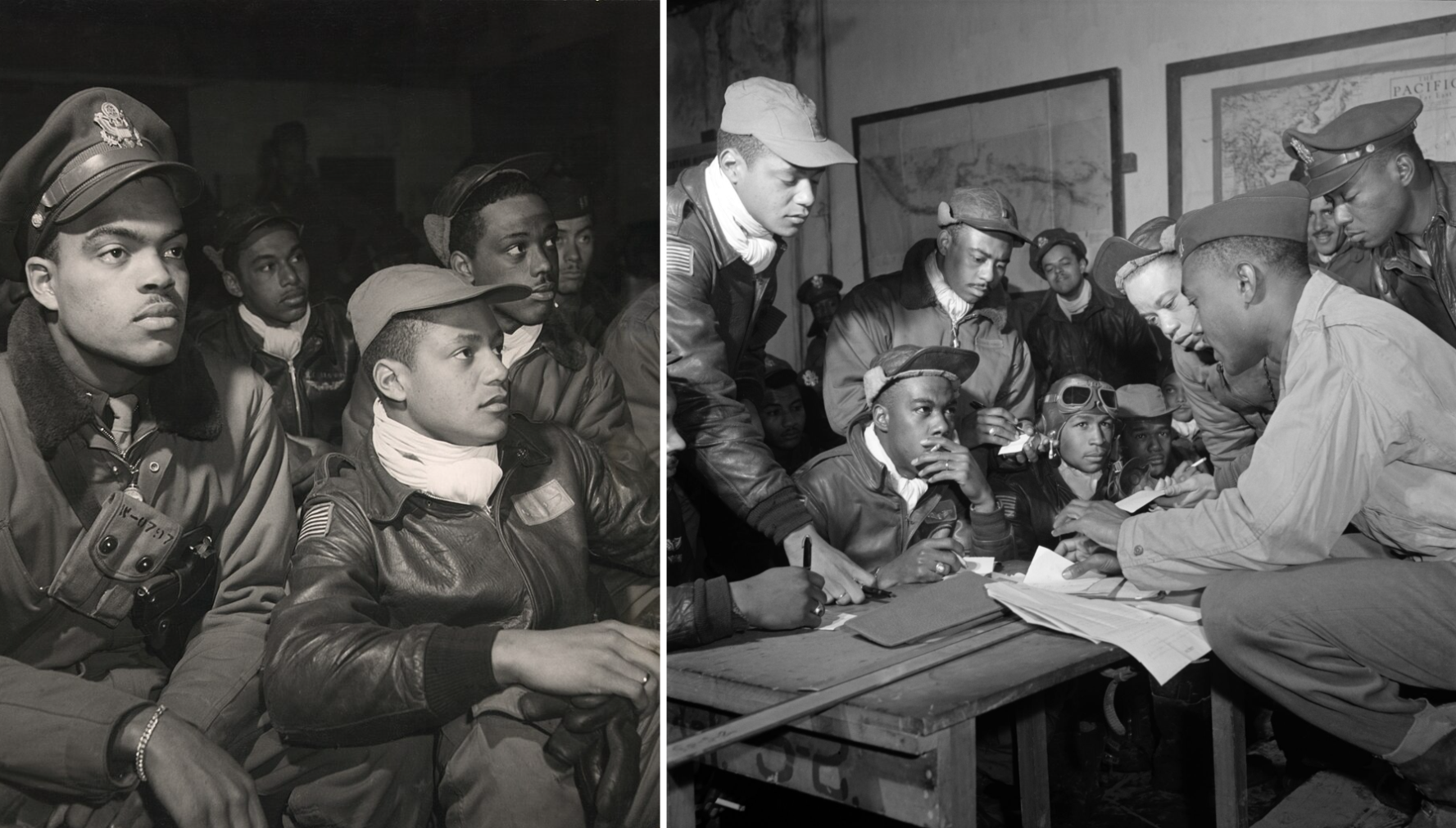

The World Wars fundamentally altered this dynamic. Millions of Black men served between 1918 and 1945. African American women also entered the military, though, in far smaller numbers. During these conflicts, African Americans recognized that the opportunity to serve would demonstrate loyalty to their country. Their patriotism, however, did not discourage their desire to combat racism and fascism at home. Black activists were able to use these conflicts to force concessions from the United States War Department.

Prior to 1918, very few African American men had ever served as officers in the U.S. military. As a result of the United States’ entry into World War I, and a forceful public campaign, hundreds of Black men were trained and commissioned as officers in the U.S. Army. In 1940 Benjamin O. Davis Sr. became the first Black general in the United States military.

That same year, the Selective Service Act went into effect. It stated that all men between 18 and 36 were eligible to volunteer for military service, and it prohibited discrimination based on race and color (though not gender). Over two million African American men registered for the draft, and over a million entered military service. Black men and women fought for equal treatment and citizenship rights while serving in all military branches and every theater of World War II.

During the conflict, William H. Hastie, Civilian Aide to the Secretary of War, became an influential advocate for Black military personnel. Hastie used his position to fight for equal opportunity and addressed issues of mistreatment and discrimination faced by Black service members. He also forcefully advocated for full integration of the armed forces both as a means of increasing military efficiency and fulfilling American ideals of equality.

For Black Americans, the struggle to integrate the military was born out of a desire to see themselves and their race respected as full citizens. Throughout the 1940s, organizations like the NAACP and activists like Mary McLeod Bethune and A. Philip Randolph pushed the case for military integration. They found a willing collaborator in President Harry Truman.

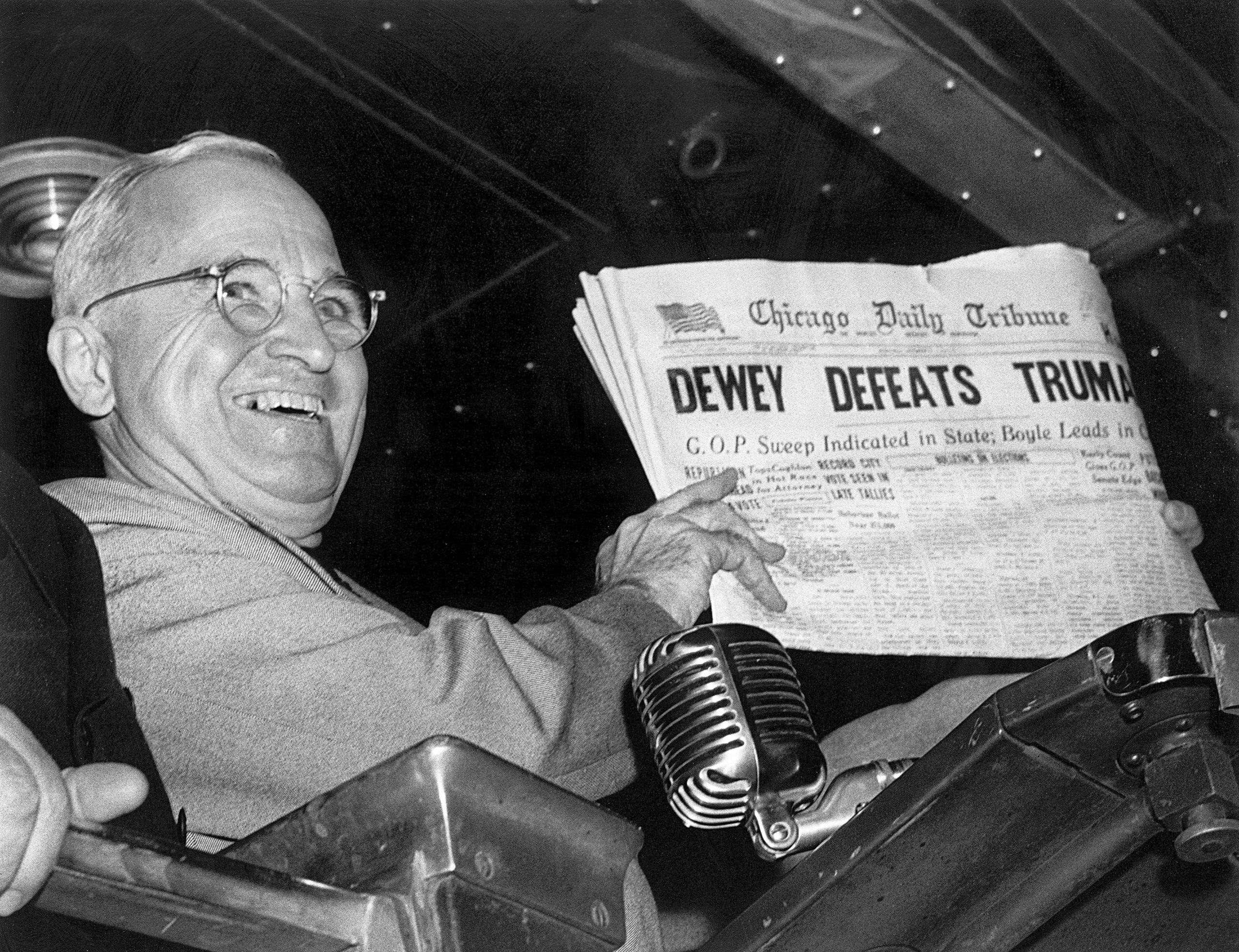

Truman’s motives for supporting Civil Rights, however, were due to careful political calculations rather than an earnest desire to uplift African Americans. While he had previously supported anti-lynching legislation, he was a staunch segregationist and opposed social integration.

Truman and his advisors decided to back Civil Rights initiatives to court the Black vote during the tight reelection campaign in 1948. Issued eleven days after the Democratic Convention had ended, Executive Order 9981 was a signal of intent to Black voters.

The controversial order led to an intraparty split and Southern Democrats, called Dixiecrats, vowed to oppose Truman and the policy. Black voters, however, backed Truman and their votes proved decisive in his victory.

Though Executive Order 9981 met significant resistance, over time, the practical benefits of the move began to outweigh the racist sentiments held by many whites. Military leaders came to recognize the inefficacy of segregation and its negative impact on morale. The Air Force was particularly pragmatic and was desegregated by 1949.

Full integration of the armed forces took over a decade and was not completed until the 1960s. Even so, it marked a significant turning point in American military history. In ensuing decades, the military became an imperfect reflection of American society and viewed as a site of inclusion and opportunity for Black people and other minorities.

![]()

Learn More:

Black Soldiers in the Revolutionary War

Executive Order 9981, Desegregating the Military

Executive Order 9981: Desegregation of the Armed Forces (1948)

The changing profile of the U.S. military: Smaller in size, more diverse, more women in leadership

He, Too Spoke For Democracy: Judge Hastie, World War II, and the Black Soldier by Phillip McGuire

The Air Force Integrates 1945-1964 Second Edition by Alan L. Gropman

Glory in Their Spirit: How Four Black Women Took On the Army during World War II by Sandra M. Bolzenius

Topping, Simon. “‘Never Argue with the Gallup Poll’: Thomas Dewey, Civil Rights and the Election of 1948.” Journal of American Studies 38, no. 2 (2004): 179–98. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27557513.