Sometime in 1851, the Oatman family, Mormans from Illinois, were following their dreams of finding Zion in an idyllic region called Bashan, a part of the Colorado-Gila Rivers basin. The journey was ill-fated from the start. By the time the group reached Maricopa Wells in today's Arizona, they were exhausted, and all but the Oatman family opted to stay for at least a few weeks to recover. The Oatmans, led by father Royce, pushed on.

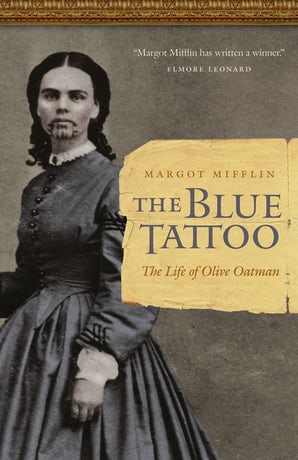

Within a week, both parents and three of their six children would be dead after a massacre. The eldest son was seriously injured and left for dead. The Yavapai Indians, who had killed the family, abducted the two middle daughters Olive and Mary Ann. The girls remained with the tribe until the Yavapais sold them to the Mohaves a year later. Mary Ann died of an unknown illness exacerbated by famine while with the Mohaves; Olive lived with this tribe for four years before they returned her to the white world when the US Army ransomed her and threatened war. During her time with the Mohave, Olive was tattooed on her chin. The tattoo was series of short and long bars in blue ink. Precise and neat, the marks remained long after her repatriation as an indelible mark of her life in captivity.

As Margot Mifflin writes in her thought-provoking new book, "this much is true (1)."

What happened next - how Olive told her story on the lecture circuit, how it was interpreted by others, the life she pursued as an adult – is considerably more difficult to pin down. These, and others, are the issues that interest Mifflin throughout this book, and Mifflin sets about to answer them by piecing together numerous printed interviews with Olive, various versions of her heavily co-written autobiography, letters with family, and anthropological studies of the native tribes she lived with.

Mifflin is driven less by an argument than she is by a quest, a quest to restore Olive's voice to the story. Olive emerges as a strong, capable woman who, at times, followed the dictates of others for her own reasons. For example, when Olive's co-writer Royal Byron Stratton arranged a public speaking tour for her, she embraced it. Mifflin suggests this enthusiasm was related to Olive's experiences with the Mohave where she had much more freedom of movement than typically afforded white women in the mid- to late- nineteenth century. Furthermore, when she settled down in marriage to John Brant Fairchild, Olive remade herself into a proper Victorian lady, complete with a child (the couple adopted) and a beautiful house. Olive did charity work, and like a many a Victorian woman, she apparently suffered from neurasthenia, a malady Mifflin argues Olive may have been more susceptible to after her years of freedom, fresh air, and activity with Mohave. Like other middle class women of the day, Olive spent time in a sanatorium following a regime of seclusion and water cures.

Mifflin finds Olive's life was heavily influenced by the men she knew. Olive's father Royce, for example, emerges as resolute man, determined to follow his dream of finding Bashan and securing life in the earthly paradise for his family. Olive's chief biographer and the mastermind of her lecture career, Stratton, was driven both by his own racism and desires for fame and fortune to tell Olive's story. Finding her experiences and the girl herself malleable enough to bend and stretch for his own purposes, he manipulated both in an effort to secure his own reputation as a speaker, writer, and anti-Indian activist.

Olive's story is fascinating; Mifflin combines an inherently intriguing story with good writing for a book that is genuinely easy to read and thought provoking at the same time. Though Mifflin tries to render Olive as fully possible, she remains a shadowy character in this book; it is often impossible to know what she really thought or felt about her experiences and why she did what she did, but Mifflin has done an admirable job of trying to recreate the young woman who was abducted at fourteen and to trace her life through adulthood until her death in 1903 at the age of 66.

Olive was both defiant and pliant, qualities that most likely aided her acculturation to the Mohave and then back to white middle class norms. At times, she used her very oddity as a tattooed former female captive to open doors to public authority and income. While much of the money and some of the acclaim went to Stratton, Olive enjoyed status derived from her experience and what she had to say about it. Her brother, on the other hand, despite his status as a survivor and crusader to recover his sisters, never enjoyed the same public role and fell on desperate financial circumstances several times over the course of his life. Likewise, Olive was able to successfully turn away from her life of travel and lecture to fashion a life as a middle class housewife. While friends and neighbors knew her story, she relegated it to the past, covered her tattoo, and built a new life with her husband and daughter.

Sometimes Mifflin's explanation of events are not persuasive. For example, Mifflin suggests that Olive suffered later in life from the bizarre condition neurasthenia, based largely on the dichotomy between Olive's life as a captive to that she experienced as a middle class woman and the treatment Olive underwent (186- 187). Given the numerous outbreaks of diseases, such as measles and cholera, that Mifflin discusses Olive was exposed to (though she never indicates if Olive contracted any of them) and the routine experience of starvation she had during the trek westward with her family and then over five years of captivity, Olive's problems may well have been physical as much as mental.

Mifflin's conclusions regarding how later authors have used Olive's story does give insight into how American concerns about women and race have changed and remained the same in the 150 years since Olive's story was first told. Olive's story, much like Olive herself, has been malleable. Make Olive a little older, nearly 20 for example, and she can become a romantic heroine, free to find true love with the Indians who have released her from the stifling constraints of middle class life. The cross-like lines of her tattoo can be transformed into a permanent, physical symbol of her Christian salvation, and her submission to the tattoo matching her submission to God.

In many ways, Olive's celebrity was secured as an outsider, if not an outright freak. She inspired a host of other women to tattoo themselves and make their own fame with fabricated captive stories. In her later years, Olive left the spotlight and sought anonymity. Oatman's rise on the wave of popularity and deliberate retreat as it began to recede are food for thought in a celebrity-obsessed culture.

The Blue Tattoo is a remarkable story of a remarkable woman. Olive Oatman adapted to her first captors, the Yavapai, and then acculturated to the Mohave. By most accounts, she was a Mohave upon her return to white America. She re-acculturated to white middle class life, hiding her fading tattoo to appear more like a "normal" white woman. Mifflin's dynamic pacing and energetic writing are a brilliant match for a story filled dynamic personalities and their transitions.

For more information on Mifflin and her work, visit: