When Betty Friedan's The Feminine Mystique was released in 1963, it split the allegedly tranquil lives of the "greatest generation" in two. On the one hand, American men were upset at Friedan's suggestion that their housewives could possibly want anything more than to see their children off safely to school, to take care of their husbands after a long day at work, and to keep their houses spotless. At the same time, a distinct group of white, educated, middle-class women were overcome with a sense of gratitude. Friedan had explained their own, as yet unnamed, frustrations.

by Stephanie Coontz.

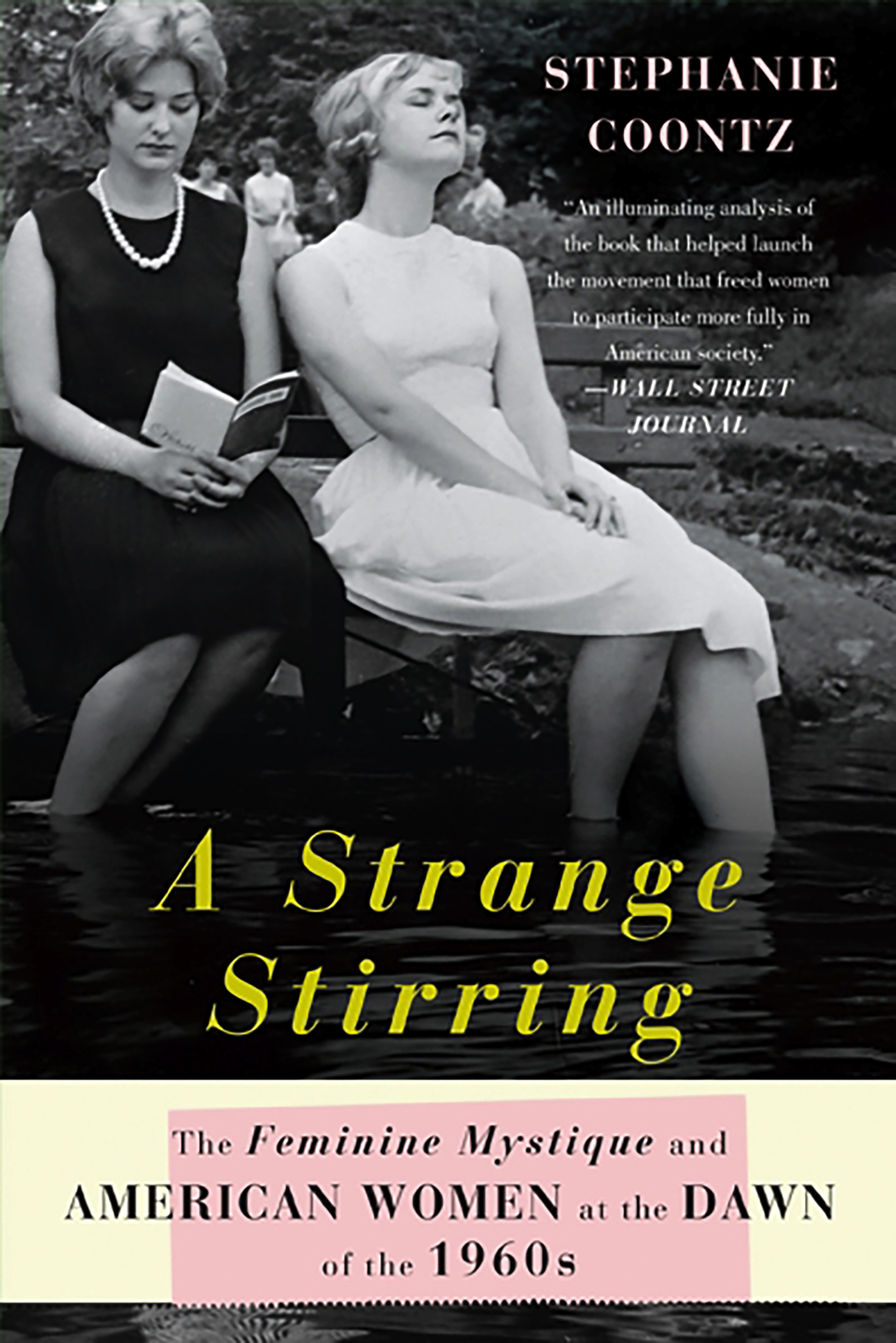

Many historians have been fascinated with Friedan's life and her, often uncomfortable, involvement in the rebirth of feminist activism in the 1970s. But Stephanie Coontz's A Strange Stirring takes the novel approach of presenting the history of the women whose experiences The Feminine Mystique recounted, alongside a biography of the book that "pulled the trigger on history" (xv).

Coontz concedes that even though The Feminine Mystique might feel dated to the modern reader, at the time it helped expose the inadequacy of the homemaker role, on its own, to provide women the kind of emotional and intellectual fulfillment they needed. Through a review of letters written to Friedan and oral histories conducted by the author, Coontz illustrates that many women who read Friedan's book were reassured that the isolation they felt taking care of home and family was not unique. This realization alone had a profound impact on a generation of women often ignored by history and, in some cases, it saved their lives.

While the post-World War II period is understood as one of prosperity, through an incredibly detailed discussion of women's lives from the 1920s-1950s, Coontz charts ever-shrinking possibilities for women in the public domain. This process culminated in the return of WWII soldiers and the banishment of many married, white women from the workplace. Encouraged to forego careers and to see their education as a means to finding a mate, these women would eventually be told that becoming a good housewife required giving up on any other aspirations.

The Feminine Mystique argued that beneath the daily routines and surface contentment of most housewives' lives lay a deep well of insecurity, self-doubt and unhappiness that they could not articulate even to themselves." (18) The history Coontz narrates in these sections is likely to shock the modern reader into disbelief, but it will also make clear that the world surrounding 1950s housewives was not as depicted on reruns of Leave It to Beaver.

From the outset Coontz makes clear that much of what people believe they know about The Feminine Mystique stems from critiques of the text rather than the claims the book actually made. In fact, in hindsight The Feminine Mystique makes few radical statements and what Friedan argues has very little in common with the feminist activism that emerged in the decade after the book's publication.

One of the biggest misconceptions at the time, which Coontz dispels thoroughly, is the belief that Friedan advocated that women should leave the home for a job, any job. Instead Friedan implored women with the education and talents to do so much more, to seek out occupations, paid and unpaid, which would improve the quality of their lives. While a much more mundane argument today, Coontz illustrates that in a post-World War II America defined by conformity, consumerism and tightening gender roles which idealized the male breadwinner family, for women to leave the home for personal fulfillment jeopardized the foundations on which post-War America rested.

Clearly, A Strange Stirring is not a thoroughly critical review of The Feminine Mystique by any means. Coontz is determined to rehabilitate the book's notorious reputation in American history. By explaining the particular restraints placed on American women, legally and socially, she reminds the reader that Friedan's book, and the women who felt it spoke to their experience, were at once a product of the times; somewhere in between wartime insecurities and the backlash against post-war inequalities.

However, while Coontz is willing largely to dismiss Friedan's failings, she must take on what has become the largest critique of Friedan's work. In no uncertain terms, Friedan did not write about "American women" as a whole. Rather, the entirety of the text is meant to explain the lives of educated, middle class white women. Friedan neglects the experiences of working class women of any race, and African American women of any class. At the beginning of her own work, Coontz makes clear that much of the history she will offer is most relevant to educated white women, but not all of it. In this way, the reader is much more prepared for the unfolding of her story than Friedan's early working class or Black readers. And with a subject like The Feminine Mystique, the reader understands Coontz's disclaimer and bears her no ill will.

But in the seventh chapter, Coontz does consider those women whom Friedan did not. In an interesting discussion, Coontz illustrates that, by ignoring the women most likely to work outside of the home, Friedan did her argument a disservice. For instance, by dismissing the sixty-four percent of middle class African American women workers, "Friedan missed the opportunity to prove that women could indeed combine family commitments with involvement beyond the home" (126). And clearly, by ignoring the fact substantial numbers of white women actually did work out of necessity, Friedan's text does more than just "lapse into elitism" (137).

Unfortunately, the history of working class and African American women offered here is much less nuanced than the rest of the text and effectively stands out like a sore thumb in the book as a whole. However, it seems clear that Coontz does not want to repeat Friedan's mistakes, and her writing is so passionate that the reader cannot help but appreciate her attempt.

In the end, A Strange Stirring is a pleasure to read, fascinating and a little bit uncomfortable, like the history recounted in its pages. While Coontz may not convince modern women, or men, to check The Feminine Mystique out from the local library, she has offered her own work as a useful replacement. It is not surprising that Coontz ends her work with a discussion of the continued need for modern women, who work outside of the home in large numbers, to be allowed to find a new balance between work and family in the ways that their predecessors were unable. And in many ways Coontz illustrates Betty Friedan might have a few lessons to teach modern America yet.