The issue of immigration is again making headlines. In July 2021, encounters between aspiring entrants into the United States and U.S. Border Patrol reached nearly 200,000, the highest monthly total since March 2000. At the same time, agricultural and service industry interests nationwide clamor for workers. Arkansas, desperate to attract labor, passed legislation making it easier for immigrants to find and keep work in the state. This month, historian Maysan Haydar shows how this tension between attracting labor and xenophobic restrictionism has been a constant through the history of American immigration.

Twin headlines have repeated across the country over the last several months, warning of labor shortages and a migration crisis.

Despite an abundance of job openings, hiring has remained remarkably flat in this booming economy. Record numbers of migrants have arrived to the United States’ southern border, the vast majority of whom are prevented from entering the country. In the fiscal year ending in 2020, immigrant and non-immigrant visas were down by more than half, representing a deficit of more than five million potential workers.

Though these seem like different issues, the history of migration and the history of labor are tightly intertwined. American immigration policy has always toggled back and forth between seeking immigrant labor and restricting entry to those deemed unassimilable. Americans need foreign workers yet resent their presence.

America’s southern border is one of the few weak spots in what otherwise has been one of the strongest launches to a presidential administration. For weeks before the January 20 inauguration, human smugglers across Central and South America known as coyotes were pressuring would-be migrants to rush the journey. They warned their clients that the border was about to open but would quickly “fill up” a quota and close again.

According to the Migration Policy Institute, category-4 hurricanes in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras have displaced hundreds of thousands of people in the past several months, pushing numbers at the southern border to top 170,000 in both March and April, 2021.

On May 31, the New York Times reported on the Biden administration’s proposals for immigration reform. As many observers expected, the plan reverses the policies of the previous administration and aims to simplify and consolidate immigration policy. President Biden directed Vice President Kamala Harris to both tackle immediate issues and to address root causes of migration in order to mitigate the problems that propel millions from their homes.

Biden has frequently described the project of improving lives abroad to decrease outmigration as a primary concern during his own vice presidency, and he looks upon his work then as a relative success. As the current administration’s immigration policy matures, it will have to reckon with the basic tension between the demand for labor and American nativism that has defined the U.S.’s approach to immigration since the late 19th century.

Migration is a natural process catalyzed by changing geography, fluctuating resources, conflicts, and disasters. Geographically large and consistently prosperous, the United States inevitably has attracted immigrants throughout its history. Yet there have been very few moments in American history when migration has not been described in crisis language, including labeling the movements of people as “waves” or “floods.”

Immigration Before Regulation

Before the late 1800s, immigration was mostly unregulated. Difficult circumstances across Europe and Asia propelled those with some means to seek opportunities in the United States. This trend dramatically magnified after 1849 because of the California Gold Rush. Laborers found ample work besides mining as the United States expanded its borders from the Atlantic to the Pacific and from the Great Lakes down to the Gulf of Mexico.

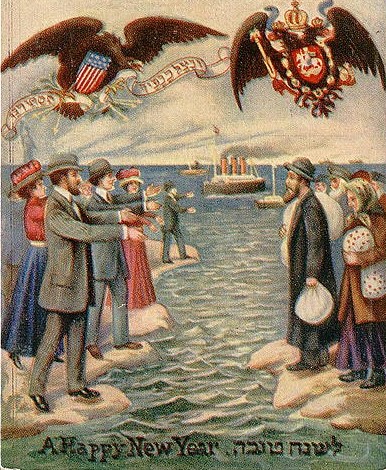

Then as now, rumors of work and opportunities dispersed far afield. Also then as now, migrants did not intend their sojourns to be permanent. Most of the history of American immigration has been populated with stories of “temporary” moves that became permanent.

Immigrant laborers often promised their families that they would be home soon with enough capital to have made the sacrifice worthwhile. Though the story differs across ethnic groups, many immigrants never returned home because they simply never made enough to do so.

“Many Chinamen have come; few have returned. Why is this?” representatives of China’s laboring community said in an 1876 address to Congress. “Because among our Chinese people few in California have acquired a fortune and returned home with joy.”

Chinese immigrant workers building the Transcontinental Railroad, late 1860s.

In the 19th century, the particulars of voluntary migration varied regionally. Asians generally arrived to the West Coast and Europeans generally arrived to the East Coast. Once in the country, free immigrants followed labor opportunities wherever they led. Chinese laborers who came to the United States after 1849 to mine or to work in ancillary businesses went east for railroad jobs and south for agricultural work as western mining waned.

Nativist sentiment spurred competition between white people and immigrants. The most damaging and long-lasting was anti-Asian agitation that began on the west coast, developed into often-violent targeting of Chinese laborers, and resulted in exclusionary policies that were enforced for nearly a century. Asian Americans were first banned from particular worksites, denied housing or services, and then prohibited from entering the country altogether.

The First Path to Citizenship

The legal processes of naturalization and citizenship were separate from immigration policy until just before World War II, and the administration of both immigration and naturalization was managed by states until the end of the 19th century.

After the U.S. Civil War, the 14th Amendment established birthright citizenship in order to provide citizenship to former slaves. Ironically, the “clarity” of birthright citizenship excluded Asian immigrants as they fit neither in the category of whites of European ancestry nor of Blacks with enslaved ancestors. The terms of the Amendment were used for several decades as a club against Asian immigrants and their descendants to deny them status and rights, including withdrawing naturalization and citizenship even if the Chinese person had been lawfully naturalized or was born in the United States.

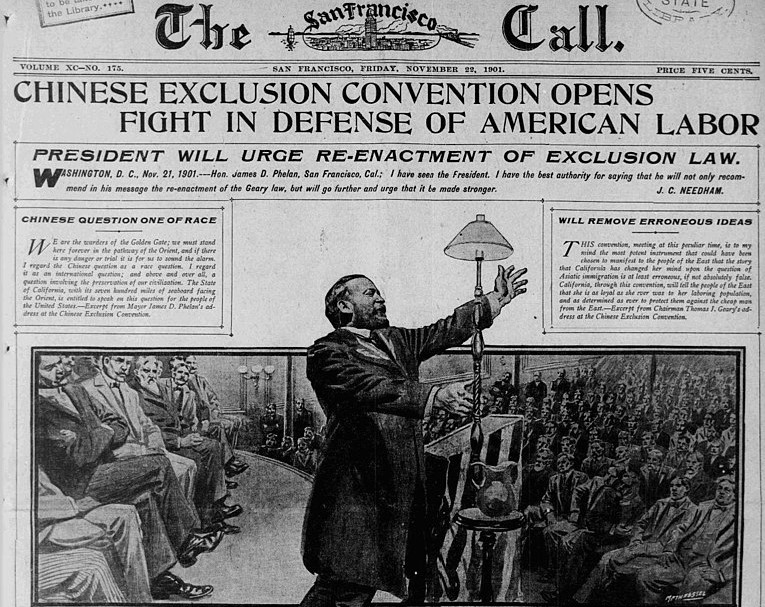

Front page of The San Francisco Call from November 20, 1901, discussing the Chinese Exclusion Convention.

Asian exclusion was the longest-lasting and most egregious transgression of the United States’ policy of ostensibly open migration and naturalization, beginning with the Page Act of 1875 and lasting until 1943. Asian exclusion began by first denying entry, then land ownership, and finally by withdrawing naturalization and attempting to overturn birthright citizenship.

The restrictions on immigration of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 were extended over time to all other Asians, with the exception of people from the Philippines, then a U.S. colony. It is worth noting as well that this nativism shot through the anti-imperialist movement during the Spanish-American War when Southern congressmen declared their opposition to “acquiring” the Philippines because doing so would legalize Filipino migration to the United States.

The denial of rights to Americans born to Chinese parents resulted in a Supreme Court decision that affirmed that birthright citizenship applied to all Americans, including those of Asian ancestry. United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898) was decided in favor of the litigant, born of Chinese parents in the United States in 1873. Yet, the Wong Kim Ark decision also shows how deeply embedded the ideas of exclusion were and how difficult the process was before Wong Kim Ark was declared a citizen because he was born in the United States.

Wong Kim Ark, in a photograph taken from a 1904 U.S. immigration document.

Upon his return from a temporary visit to China in 1895, Wong was denied re-entry to San Francisco by the Collector of Customs, who invoked the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. The U.S. District Attorney arguing against his case (in addition to the dozens of immigration officials involved in such decisions before it made it to the highest court) used his Chinese heritage as the sole argument against his right of entry. His “race, religion, language, color and dress... [necessitates that he] is not entitled to land in the United States or to remain therein because he does not belong to any of the privileged classes enumerated in any of the acts of Congress.”

Wong remained on a freighter for five months off the coast as the case wound its way to the U.S. Supreme Court. The 6-2 decision (with one abstention) interpreted the 14th Amendment as offering all persons born on American land or territory jus soli (birthplace) citizenship rather than the more-common jus sanguinis (birth parent) citizenship. (Birthplace citizenship declares all persons born in the United States American; birth parent citizenship declares all children born to American parents American, regardless of where the children themselves are born. In both cases, the citizen does not have to make a case for their citizenship, it was a right granted upon their birth.)

Reactions Against the “Huddled Masses Yearning to Breathe Free”

Prejudice toward immigrants was not limited to those from Asia. Nativists, many of whom were immigrants themselves or descendants of recent immigrants, argued that laborers from southern or eastern Europe were deficient and unassimilable “by nature” and should be severely restricted from migrating to the United States.

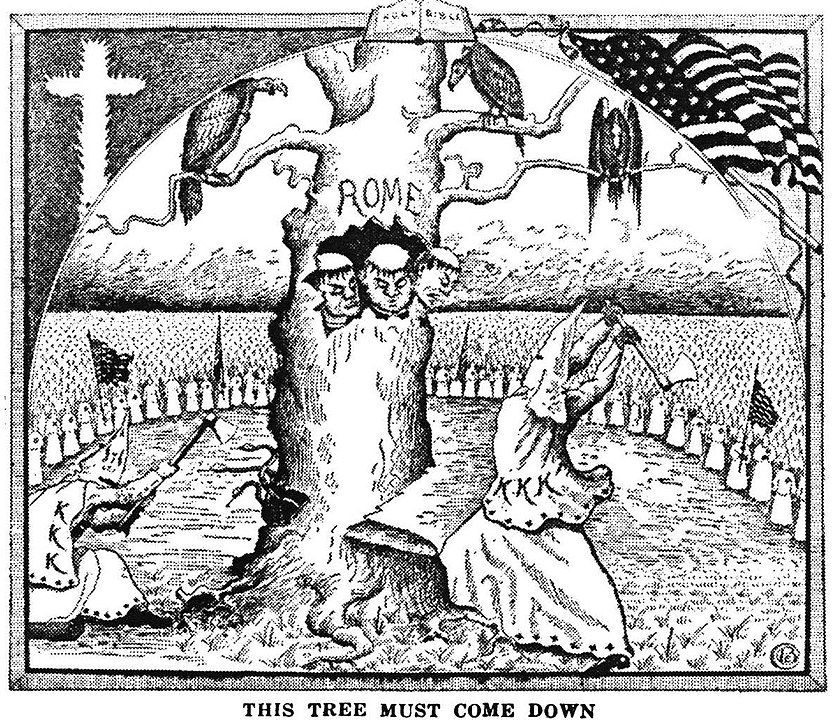

An illustration in The Ku Klux Klan in Prophecy (1925) depicting anti-Catholic sentiments that were fueled by waves of Catholic immigration in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The pattern began as anti-Catholic agitation. Much as the Chinese were accused of having divided loyalties, mid-19th-century Catholic immigrants were viewed suspiciously and accused of taking orders from the Pope. The nativist sentiment of “Know Nothings” was echoed in later incarnations like the anti-Catholic American Protective Association, the Immigration Restriction League, and the Ku Klux Klan.

Nativist movements became odd bedfellows of upper-class urban Protestants, organized labor, and birth-control advocates. Uniting them was the popular belief in eugenics, purportedly a “scientific” agenda to end poverty and improve society through restrictive reproduction.

Vastly oversimplifying biological and evolutionary concepts, the nativists used the language of rational argument and science to promote a restrictive immigration policy that favored English and Germanic migration to the United States and curtailed it for Italians, Southern Europeans, and Eastern Europeans, many of whom were Jewish.

Biologists and other scientists eventually spoke out against eugenics, but the damage was done. Restrictionists agitated for and succeeded in passing federal restrictions after World War I that created quotas by country, limiting entry to a fraction based on a group's presence in the 1890 Census. From 1921 until 1965, there was essentially no migration to the United States among the excluded and restricted groups.

Immigration Policy as Foreign Policy

In the aftermath of World War II, several broad developments reshaped U.S. immigration policy without fundamentally changing the underlying economics of migration or dissolving widespread racial bigotry among Americans.

First, World War II resulted in an enormous forced migration, certainly one of the largest in human history and rivaled only by the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. As borders were redrawn and a new international order sewn, some fourteen million displaced persons—possibly many more than that—were forced to resettle.

The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights included the right to seek safe asylum as one among them. As a signatory, the United States was obliged to weave new definitions into standing immigration law. Even before the Declaration was adopted, President Harry Truman signed the Displaced Persons Act, which brought more than 200,000 European refugees into the country over the following four years, without regard to immigration quotas. Though it amounted to the first official recognition of new refugee definitions, it was hardly generous.

Forced resettlement of Poles from Reichsgau Wartheland following the German invasion of 1939.

Asylum applicants were carefully vetted, with a bias for assimilability and skill level; 30% of the slots were dedicated to agricultural workers as a way to minimize Jewish applicants. The Act excluded Asians, and yet because the law allowed foreign nationals already in the United States to secure permanent residency, 3,645 Chinese changed their immigrant status.

The Cold War also introduced new dynamics into U.S. immigration policies. Briefly allies in the war, the United States and the Soviet Union competed for laborers and looked to eastern Europe, Asia, and Africa in order to solicit their best and brightest.

Headlines in the New York Times from the 1950s warned that “Soviet Seeks More Labor” and that they were meeting their goals. For their part, American policy makers and congressmen wanted both to use immigration policy as proof of the nation’s opposition to political tyranny and to attract the most talented people from the developing world.

Yet even here the exclusionary impulse was evident.

The 1952 McCarran-Walter Act maintained the quota system and the heavy bias in favor of Western European visa applicants. But in a bid to shore up the nation’s reputation in Asia, the Act tweaked the blanket exclusions of Asians and abandoned the racial prohibitions on naturalization.

McCarran-Walter also established preferences for skilled workers and family members of people already in the United States. Meanwhile, the law provided the executive branch leeway to use refugee status to skirt congressional oversight. The Eisenhower Administration used this provision to bring 32,000 refugees from the failed Hungarian revolt of 1956, and under Kennedy some 200,000 Cubans were permitted entry.

Refugee and asylum policy continued to serve as adjuncts to U.S. foreign policy. The Ford administration supported the evacuations of over 100,000 Vietnamese after the Communist victory there. In 1975, the “Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act” allowed the relocation of refugees from Vietnam and Cambodia with the addition of Laos the next year.

The United States formally adopted the United Nations definition of “refugees” in 1980 and created a separate set of admissions apart from labor and family reunification immigration visas. Executive actions were quick responses to immediate crises. Some examples of this are Ronald Reagan’s executive order to protect Nicaraguans in 1987 and George H.W. Bush’s response to the panic of Chinese abroad after the Tiananmen Square protest and fallout in 1989.

A New Attitude Toward Immigration

Thus, Cold War policy led to a gradual chipping away at the extreme restrictions of the 1924 National Origins Act. As the national mood liberalized in the early 1960s, a full-scale reorientation of immigration policy became possible.

New York congressman Emmanuel Celler, among the most progressive congressional figures, took advantage of the moment to propose a complete reformulation in the form of the Hart-Celler Act of 1965. Hart-Celler abolished the quota system and prioritized family ties and work skills; for the first time, caps were placed on intra-hemispheric immigration.

When Lyndon Johnson signed the new law in October 1965 during a modest ceremony at the foot of the Statue of Liberty, he promised that though the act was of great importance, it would not have a notable impact on the ethnic composition of the nation. The bill’s floor manager in the Senate, Robert Kennedy, insisted simply that “it will not upset the ethnic mix of our society.” They could hardly have been more wrong.

Indeed, Hart-Celler set the basis for three major trends that have had powerful repercussions. First, it revived the United States as a nation of immigrants. The percentage of immigrants in the population has almost tripled, from 5% to nearly 15%, and the percentage of non-white Americans has more than doubled.

Second, opening the process to non-whites while instituting skill preferences has allowed the United States to attract professionals from around the world, particularly from Asia and the Middle East, so much so that much of our STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math), medical care, and high-wage labor depends on new Americans. Nearly one-third of American physicians are foreign born, as are 40% of its engineers.

A sign welcoming people to Little Italy in Manhattan.

And to a large extent, the bill did not upset the ethnic mix so much as expand it. Because of the family reunification visas, not only did the Cold War professionals from across the globe settle in America but also brought their extended families including those who made the ancillary businesses and restaurants that import familiar items from “back home” and make the food that helps ease the transition into American life.

The “ethnic mix of our society” from our Little Italys to Koreatowns and “Tehrangeles” better represents the “nation of immigrants” in the 21st century than in any previous period.

Third, though the new immigration regime was expansive in these ways, it too contained exclusionary provisions. By capping immigration from Latin America, it interrupted a long-established pattern of circular labor movement, especially from Mexico. When coupled with the end of the clearly exploitative Bracero program in 1964, Hart-Celler made “illegal” the movement of Latino workers that had been previously encouraged according to labor demands in the southwest.

Mexican workers from the Bracero Program working on a farm.

Because neither labor demand nor the motives of laborers in the region changed, Hart-Celler created the conditions for the ongoing “crisis at the border.”

For much of the period since 1965, immigration policy has been shaped through bi-partisan agreements in Congress. It was Ronald Reagan, after all, who signed off on the as-yet most significant path to citizenship for previously undocumented migrants.

The Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 passed both chambers with bipartisan support and with significant majorities and legalized the status of almost three million people. In a precursor to the DACA “Dreamers,” Reagan issued an executive action to make legal the status of undocumented children in those families, affecting more than 100,000 families.

Part of the border wall between USA and Mexico near Ajo, Arizona.

That bipartisanship seems to have all but died over the past decade, as the resurgence of identity politics on the American right has pushed the Republican Party to reassert exclusionary policies. When the party’s standard bearer unashamedly denounced sources of non-white immigration as “shithole” countries and called for more immigrants from “places like Norway,” the echoes of the racial bigotry at the heart of the 1920s exclusions could hardly be clearer.

There may be another similarity between Trump-era exclusionism and the 1920s. In both cases, exclusionary policies were adopted long after decades of immigration had already irrevocably changed America’s ethnic-racial makeup. As in the 1920s, any attempt to preserve some imaginary past of homogeneity based on the predominance of white people is doomed to fail.

Even as today’s restrictionists demand walls and deportations, the emerging Census numbers show the slowest population growth in 80 years. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce is lobbying Congress to expand visas for both highly skilled and seasonal temporary workers. If small cities in the American heartland hope to avoid decline, they will have to look to immigrants to fill jobs, energize their economies, and maintain their populations.

Places such as Northwestern Arkansas, where Bentonville stands as an icon in the annals of old-fashioned American entrepreneurialism, now clamor for the federal government to reopen the immigration process that actually made the region’s economic growth possible 15 years ago. In 1990, the New York Times recently reported, the area was 95% white. That percentage is now 72% after a steady influx of Asian software engineers and Hispanic meatpacking workers.

Local businesses are discovering that they are stuck between the two poles of American immigration history, their present condition captive to the past.

Ronald Takaki, Strangers from a Different Shore

Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns

Jhumpa Lahiri, The Namesake

Sarah Gualtieri, Between Arab and White

Luis Alberto Urrea, The Devil's Highway

Bernard Malamud, The Complete Stories

Pete Hamill, A Drinking Life: A Memoir

Sonia Shah, The Next Great Migration