Reading the news in 2021—in either dead-tree or electronic formats—it might seem like refugees are everywhere.

Syrian and Eritrean refugees cross the Mediterranean, bound for Europe in less-than-seaworthy boats; Rohingya refugees from Myanmar occupy camps in Bangladesh; and Honduran and Guatemalan refugees seek asylum along the southern border of the United States, to name just a few movements that have sparked media coverage.

Rohingya Refugees in Bangladesh, 2017.

But what distinguishes these refugees from others seeking to move across international borders, and why is it important to identify individuals—or groups—as “refugees”?

On July 28, 1951, representatives of 26 states, meeting in Geneva under the auspices of the United Nations, signed the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. Building on Article Fourteen of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which established the right to seek asylum from political persecution, the drafters of the convention sought to provide a standard definition of refugee status within international law.

According to the new Convention, a refugee was a person who “owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.”

This agreement continued the work begun some 30 years earlier by the office of the High Commissioner for Refugees (HCR) of the League of Nations. Created on June 27, 1921, the position of High Commissioner was subsequently offered to the Norwegian Arctic explorer and diplomat Fridtjof Nansen.

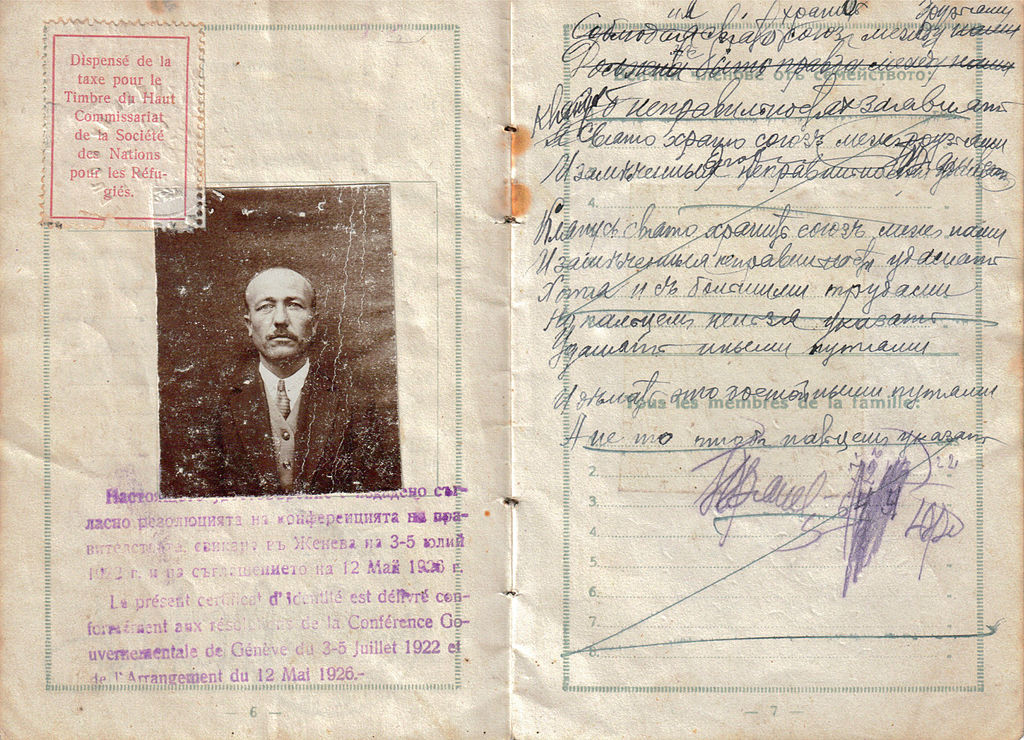

An example of a Nansen passport, which allowed stateless persons to legally cross borders.

The HCR provided internationally recognized travel documents to individuals who had been rendered stateless in the midst of the First World War and subsequent conflicts. These were dubbed “Nansen Passports,” and Nansen was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1922 for his efforts in support of refugees. Nansen’s name quickly became so synonymous with international refugee relief that the HCR was renamed the “Nansen Office” after his death.

The 1951 Convention, with its roots in the work of Nansen and others over the previous three decades, still influences how the world views refugees today. Taken together, tens of millions of people are, to use the convention definition, currently outside of their country of nationality, are unwilling to return out of fear of persecution, and are therefore taking advantage of their right to seek asylum elsewhere.

Both the initial leaders of the Nansen Office—including Nansen himself—and the drafters of the 1951 Convention were working in the aftermath of global conflicts and political upheaval. Most of the holders of Nansen passports between the world wars were Russian and Armenian refugees who were not recognized as citizens of the USSR and the Republic of Turkey.

German refugees move west from formerly German territories, 1945.

World War II and the Cold War created more than ten million European refugees who sought United Nations assistance. Millions more internally and externally displaced people, including ethnic Germans expelled from Central and Eastern European countries and refugees in Asian countries, were ineligible for UN assistance. Only with the 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees did non-European refugees come to be defined in the same way.

In both cases, the dangers that refugees sought to flee were understood in political, state-based, terms: wars, imprisonment, political or religious persecution, all perpetrated by governments or their representatives. Because of this, refugee protection in both 1921 and 1951 was conceived as international, politically neutral, and purely humanitarian.

Fridtjof Nansen’s stated goal was to protect refugees from becoming political pawns, while the 1951 Convention made clear the importance of international cooperation for refugee relief and protection as a way to defuse tension between governments and ensure that states bordering conflict areas would not be forced to carry the entire burden of granting asylum status to refugees.

Fridtjof Nansen at an Armenian orphanage, 1925.

In return, the drafters of the Convention assumed that refugees would want to settle in the state granting them asylum or seek resettlement in a third country. In either case, the expectation was that refugees would quickly assimilate into their new society and secure permanent residency, if not citizenship.

Of course, the concept of “refugee” only exists as a category to distinguish a particular type of migration. Many people move, both within countries and across international borders, for reasons that seem unrelated to a fear of violence or persecution at the hands of an oppressive government. Perhaps they want a higher-paying job or better educational opportunities for their children.

Drawing a line between such migrants and what one might term “true refugees” can prove deceptively challenging. What if a person is fleeing the threat of violence or persecution carried out by groups not associated with any government? What if the danger they fear has been created by a changing climate, the flooding of low-lying areas, or food insecurity due to drought and desertification?

The Zaatari refugee camp for Syrian refugees in Jordan, 2013.

Such refugees must find ways to fit their experiences into the rather narrower expectations set up by the 1951 Convention definitions, or else they have no hope of being granted asylum, let alone a chance at resettlement elsewhere. In addition, tens of millions of people displaced from their homes around the world today remain within the borders of their home country. Despite appearances, because they have not crossed an international border, they are denied the international rights accorded to refugees.

Seventy years after the last major rethinking of the international refugee regime—the 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees notwithstanding—it is time to rethink how we define “refugee.”

Recent international agreements like the New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants (2016) and Global Compact for Safe, Orderly, and Regular Migration (2018) are a start, but it is the colloquial definitions of “refugee” and related terms, used in the media and other public settings, that need to adapt.