Remote and inhospitable. That's the way many of us think about the Arctic. In fact, the Arctic has been exploited for its resources for a long time. That exploitation has only increased as climate change has caused the Arctic to melt away. But as historian John McCannon tells us this month the consequences of climate change at the top of the globe are already having an impact on all of us, making what happens to the Arctic a lot closer than most of us realize.

We have always been killing the Arctic.

By “we” I mean non-native Westerners, who began entering the higher latitudes in substantial numbers around 1200 CE and who have left their imprint on the region ever since.

Whether settling there permanently—often to the detriment of indigenous populations—or sojourning there to hunt, fish, trap, or mine, we have carried out a ceaseless campaign of what I call “Arcticide”: the persistent and accelerating degradation of high northern environments to the point that their demise is nigh inevitable. Of this long and all-but-consummated crime, we are, all of us, guilty.

One can fairly ask why Arcticide merits any more attention than other ecological crises currently unfolding in every quarter of the globe. What of coral bleaching along the Great Barrier Reef? Or the clear-cutting of Amazonia, or the shrinking of the Aral Sea? These, too, rank as tragedies of the highest order.

The Arctic, defined as the lowest latitude affected by the northern polar night, possesses a particularly fragile ecosystem. What is more, climate conditions there serve as a bellwether for planetwide trends. Indeed, rather than simply foreshadowing weather patterns in the south, Arctic meteorology has increasingly come to affect them.

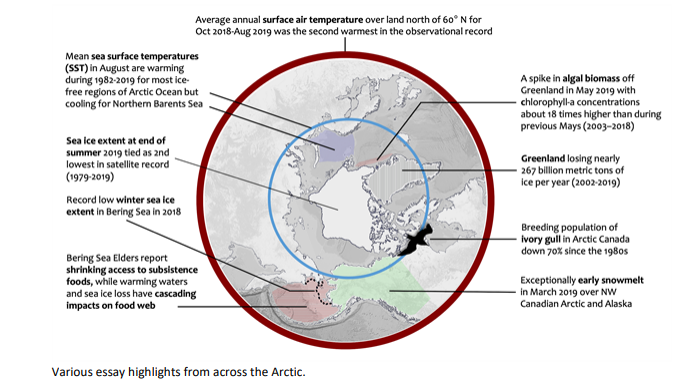

The Arctic’s terminal decline, then, warrants close examination and more than a little concern. Each year, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) issues an Arctic Report Card. The results are predictably grim.

Arctic temperatures continue to soar. The oceanic ice pack dwindles, country-sized patches of permafrost lose their shape and solidity, wildfires rage, and dozens of species are menaced by extinction. The hottest Arctic temperature ever, a sweltering 100.4° F, was recorded in the Siberian settlement of Verkhoyansk in summer 2020.

The failing grade belongs to us, not to the Arctic. The following essay traces this regrettable delinquency, which was neither sudden nor unpredictable.

Industrial-Scale Slaughter in a Pre-Industrial Age

Trade routes and territorial mastery played their roles in motivating Europe’s northern incursions into the Arctic, but killing was king.

One of the earliest medieval references to Arctic venturing is the Norse chieftain Ohthere’s account given to Alfred the Great around 890 CE. He claimed to have sailed to the Scandinavian Arctic and Russia’s White Sea coast, and bragged of immense quantities of walrus tusks, bearskins, and marten and seal pelts he had collected.

The whale-oil refinery near the village of Smeerenburg by Cornelis de Man (1639).

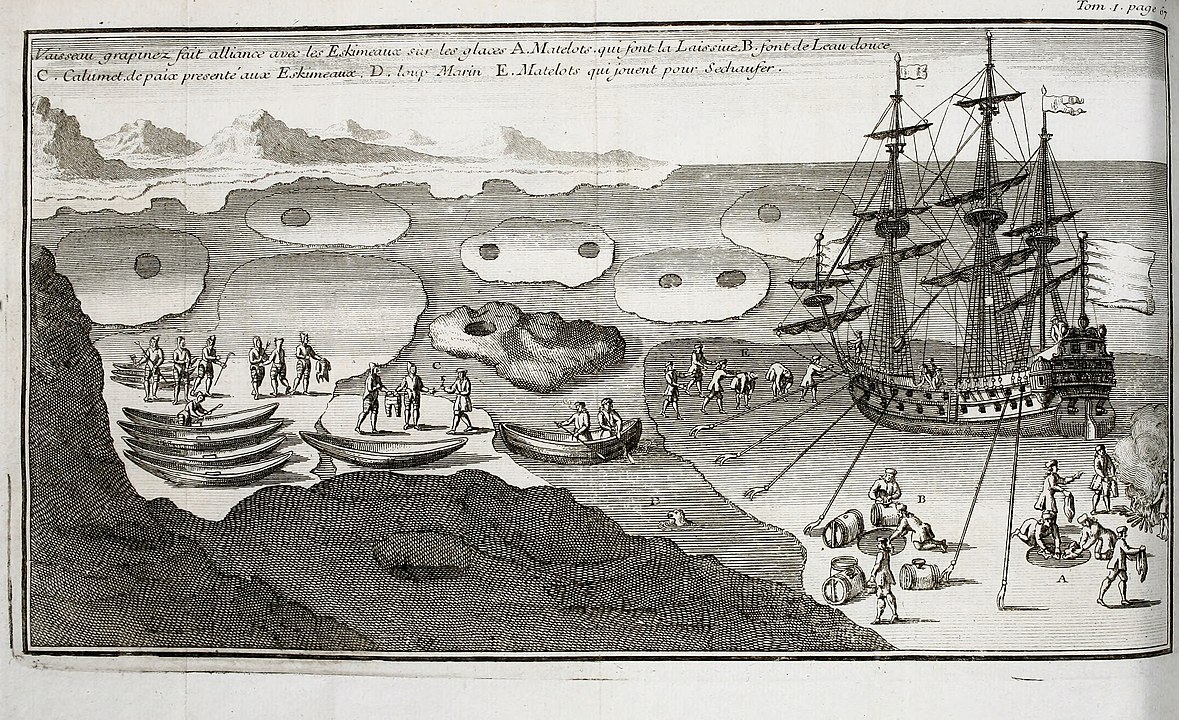

In the early 1600s, as ships from the south plied the Greenland and Barents seas in search of bowhead whales, fanciful stories arose about the Dutch outpost Smeerenburg, or “Blubber Town.” Named for the huge vats placed there to render whale blubber into oil, Smeerenburg emerged as a fleshy El Dorado, complete with shops, bakeries, and even a casino and brothel. Smoke billowed endlessly into the sky as the grisly business of processing dead sea mammals into profits continued night and day.

Smeerenburg starkly illustrates the core purpose of outsiders who invaded the Arctic from the medieval period onward: to hunt, on land and at sea.

This is not to say that the Arctic had been free of blood beforehand. Natives significantly affected their habitats, and there was nothing Arcadian about how they gutted and dried cod, flensed whale blubber, or butchered caribou. Still, the harm was limited by their small populations, simple technologies, and keen sense of what their home environments could bear. Indigenous northerners lived within sustainable parameters.

The influx of European freebooters, merchants, trappers, and voyagers threw things out of balance. Whatever their nationalities, the newcomers hunted and fished on a scale unimaginable to Inuit, Aleuts, native Siberians, or Sami. They brought in their wake not just a burdensome colonial presence consisting of missionaries, soldiers, and tax collectors, but also a deadly assortment of diseases ranging from smallpox and measles to syphilis.

Humans killed staggering quantities of land and sea creatures in the northern latitudes between 1500 and the onset of the industrial era. They overharvested cod and other fish throughout the North Atlantic, from Norway’s Lofoten Islands to the banks off Newfoundland. Similar predations depleted the North Pacific’s stocks of salmon, char, and cod.

Bowhead and Atlantic right whales began disappearing from the northern waters east of Greenland in the first half of the 1600s, then off the coasts of North America and western Greenland in the late 1600s and early 1700s. In the years leading up to 1700, the Dutch alone killed 500 bowheads annually, and other nations strove to keep pace. Ships from the British Isles are thought to have taken 38,000 bowheads just from Davis Strait. As with the fishing industry, the slaughter of great whales spread to the Pacific in the 1700s, with equally murderous effect.

A woodcut depicting whale-fishing, 1574.

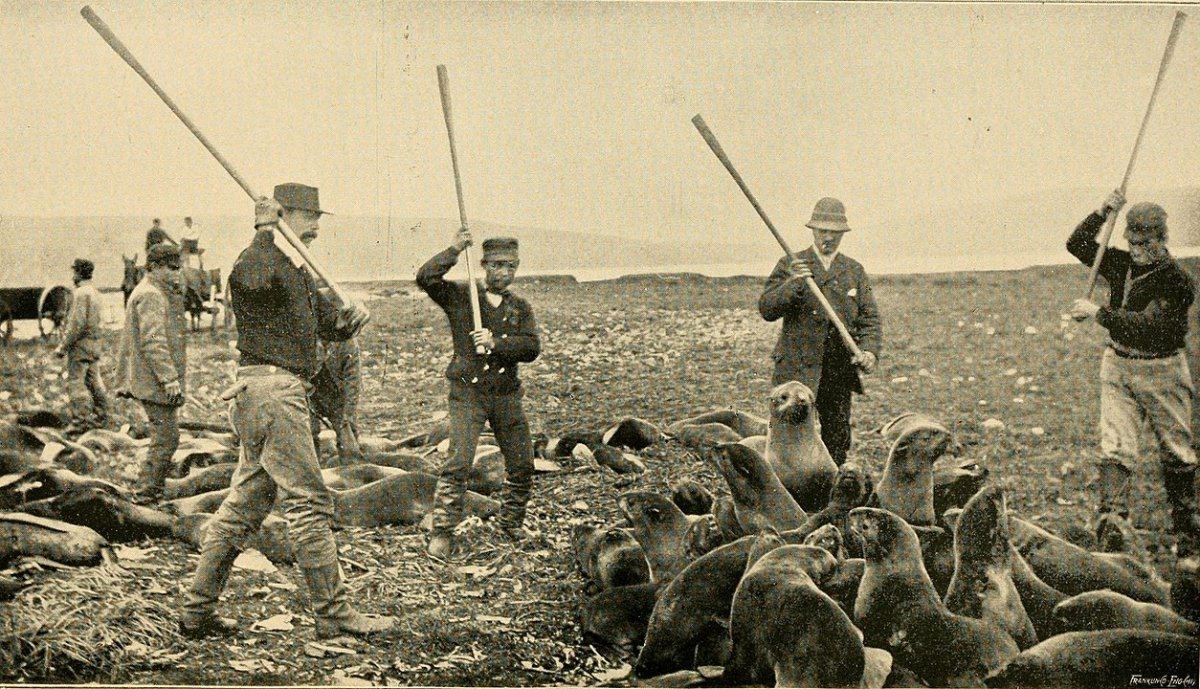

Throughout the circumpolar north, walrus and more than half a dozen species of seal were killed in numbers beyond calculation, for ivory, flesh, oil, and, most of all, the seals’ lustrous and water-resistant fur. The Atlantic population of gray whales went extinct in the 1700s, and narwhals were prized for their unicorn-like ivory tusks.

Fur in many forms became the “soft gold” that inspired Arctic colonization throughout Eurasia and North America. Skins were stripped from polar bears, Arctic fox, and lynx. Beaver pelts were taken from Canada, fur from Siberia’s majestic sable and the sea otters and fur seals of the North Pacific. All these and others were hunted rapaciously from the 1500s through the 1700s.

That slaughter drove Russia’s eastward expansion to the Pacific and the formation of joint-stock entities like the Hudson’s Bay Company in Canada. During the 1600s, Russians took out of Siberia nearly 70,000 fox, ermine, and sable pelts annually, and by the late 1700s, they were reaping 350,000 pelts per year from the North Pacific. Between 1769 and 1868, the Hudson’s Bay Company harvested from the Canadian frontier almost 5 million beaver skins and furs from another 5 million animals.

Leaving aside their deleterious impact on native populations, hunters and fishers damaged ecosystems in other ways, most notably as they fed themselves while in the wild. A host of animals were used for food—auks and puffins proved easy targets, as did the eggs of dozens of bird species—and in the North Pacific, the docile Steller’s sea cow was extinct by the end of the 1760s.

The harm done in the high north was monstrous, but it was limited by the fact that it had to be committed directly and up close, leaving blood on the perpetrators’ hands. In years to come, the damage would become easier to inflict, even as its scope widened.

“Modernizing” the Arctic

In 1883, the Swedish-Finnish mineralogist and explorer Nils Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld—best remembered for leading the first successful voyage through the Northeast Passage linking the Atlantic to the Pacific via the northern coasts of Scandinavia and Russia—paid a visit to the Greenland ice cap.

During this journey, he noticed that some of the ice there was coated in places by a black powder he dubbed cryoconite after examining it more closely at home. Composed of carbon, zinc, and iron, this dark substance absorbed sunlight, causing the ice below to pit so badly that, as Nordenskiöld wrote in the American magazine Science, “it was impossible not to stumble into [these holes] at every moment.”

A large stream of meltwater emerges from an upstream supraglacial lake in the Greenlandic ice in 2012. The darker shapes are minor streams covered by cryoconite which covers the ice sheet (left). A crevasse created by water drilling a hole into the glacier ice. The cryoconite is the black layer of soot over the ice. Langjökull glacier. July 2006 (right).

Cryoconite, as it happened, was the by-product of industrial activity in Europe, dust vented into the air by factories, furnaces, and refineries, then wafted by the winds onto the northern wilderness. What Nordenskiöld had encountered was a new industrial-age reality imposing itself upon the Arctic. Not only had the outside world come to influence the region more powerfully, it was now capable of doing so from afar.

By no means did the destruction of Arctic animal life cease after 1800. If anything, northern fishing, not to mention the harvesting of seals, whales, walrus, and all the fur-bearing creatures mentioned earlier—where they still survived—escalated and was systematized. For a grim symbol of the times, one need look no further than the invention of the grenade-tipped harpoon gun, patented by Svend Foyn of Norway in 1870, by itself raising the whaling industry to new heights of lethality.

In this era, though, the most consequential injuries to the Arctic involved other forms of resource extraction and amore direct plundering of the land itself. The Arctic in the 1800s was increasingly viewed as a source of new forms of wealth waiting to be tapped by the enterprising and the bold. (For natives in all sectors of the north, this imperial acquisitiveness presaged new levels of economic marginalization and colonial subjugation.)

The first Arctic commodity reaped on a large scale was timber—a seemingly inexhaustible resource, whether one felled trees in Canada’s northern woods or in the vast Eurasian taiga. But lumber paled in comparison with the north’s astounding mineral wealth, which industrial-era science and technology were rendering at once more discoverable and more necessary.

In northern Sweden, the extraction of copper, silver, and especially iron, pursued on a relatively small scale in the 1600s and 1700s, expanded into a mammoth enterprise in the 1800s, centered on the famed Kiruna mines and the consequent 300-mile Malmbanen railroad.

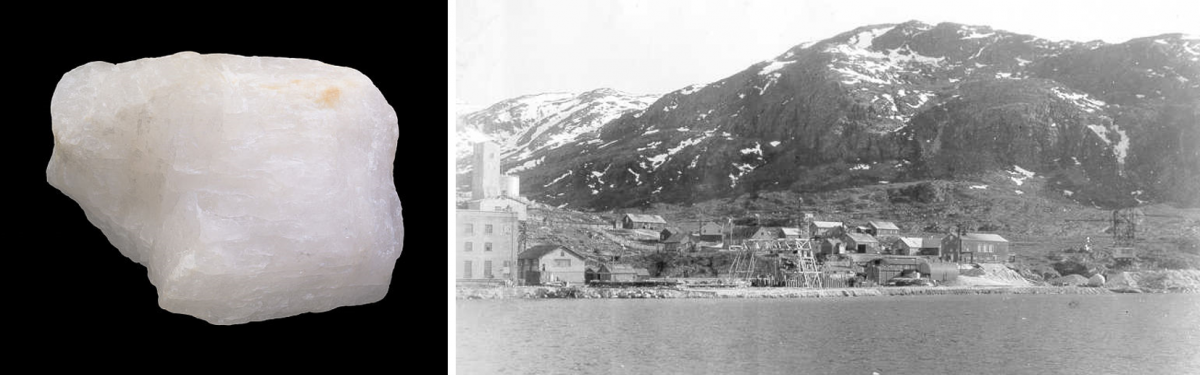

Commercial mining of Spitsbergen coal began in 1899, with the founding of the island’s chief city Longyearbyen shortly thereafter. Miners raced to extract diamonds, nickel, zinc, and molybdenum from lands across the Arctic. In southwestern Greenland, the Ivittuut district attracted miners seeking cryolite, once used for processing aluminum and, according to the Royal Society of Chemistry, the only mineral to have been driven to “extinction” by human activity.

A piece of cryolite from the Ivittuut Cryolite deposit in Greenland (left). The cryolite mine in Ivittuut, Greenland, 1940 (right).

Most tempting of all was the gold. In Russia, its discovery along the Lena River in the 1860s drew thousands to the remote wilds. By the 1890s, these “moilers under the midnight sun,” to borrow a phrase from the Canadian poet Robert Service, were joined by counterparts in North America, who flocked in even greater numbers to Alaska and the Yukon. Virtually overnight, the Klondike gold rush of 1896-1899 added more than 30,000 non-natives to the local population, creating boomtowns like Dawson and placing new environmental stresses on the landscape.

Oil and natural gas, though not yet as crucial to the world economy, were discovered in Western Siberia, Canada’s Mackenzie Valley, and Alaska’s Prudhoe Bay. Alaska’s first oil wells were sunk on the Iniskin Peninsula in 1898, with commercial production commencing in 1911.

The environmental harm caused by these developments went largely unnoticed by Western audiences, who thrilled to the Arctic sagas that filled the pages of the press from the 1840s through the 1910s, regarded as the “golden age” of polar exploration.

In the Anglo-American tradition, this era began with the disappearance of Sir John Franklin’s ill-fated 1845 naval expedition to Canada in search of the Northwest Passage. The quest for the missing men, all of whom perished in 1846-47 after their ships were trapped in the ice, became a years-long cause célèbre.

Dozens more expeditions followed, their missions gradually expanding to encompass more precise mapping of Greenland and the North American Arctic, the discovery of the Northwest Passage (in 1850, by Robert McClure), scientific research in disciplines ranging from oceanography to meteorology, and the imposition of tighter state control over the northern periphery (and, to their dismay, the native herders, hunters, and fishers dwelling therein).

Most of all, this period witnessed the famous “race for the Pole.” Decried as a trivial and distracting “steeplechase” by sober researchers such as the Austro-Hungarian mariner Karl Weyprecht, it excited unparalleled interest in a public readership infused by 19th-century nationalism and flooded with cheap newsprint.

The Euro-American imperative to ransack Arctic treasures was so embedded in the Zeitgeist of the late 19th century that author Jules Verne, in his ripped-from-the-headlines fashion, made it the theme of his 1889 novel The Purchase of the North Pole. In it, the Baltimore Gun Club schemes to melt Arctic glaciers with a super-cannon fired from the top of Mount Kilimanjaro, thereby gaining access to coal reserves beneath the ice, heedless of the resulting death and destruction.

An illustration from Jules Verne's novel The Purchase of the North Pole drawn by George Roux.

Happily for the denizens of Verne’s fictional universe, his antiheroes fail to realize their nefarious plans, and the Arctic’s countenance remains as icy as ever. In real life, however, myriad forms of environmental devastation continued—more prosaic but no less baleful.

The Canary in the Ice Sheet

The 20th century accelerated all these trends, and the 21st has seen them coalesce into a deadly feedback loop from which the Arctic grows increasingly unlikely to escape.

During the 1900s, nation-states brought circumpolar territories fully under their jurisdiction and tamed them in myriad ways.

Brute-force modernization imprinted the north with an infrastructural lattice of sea and river ports, air routes, roads, and railways. In the Soviet Union it was accomplished by forced resettlement and prison-camp labor, with the GULAG serving as a grim underside to Stalin’s exhortations to “storm the Arctic.” Scandinavia and North America used less coercive, though no less environmentally destructive, industrial methods.

Mines, factories, fishing and hunting stations, military installations, scientific and meteorological outposts, and new communities proliferated, especially during World War II and even more so during the Cold War.

The previous century’s hunger for Arctic minerals was matched by a new and growing thirst for the region’s massive oil and gas reserves. Levels of pollution from sewage, fuel, and trash spiked in all sectors of the Arctic.

While international media coverage focused in the summer of 2020 on the disastrous spillage of more than 40,000 tons of diesel in two separate incidents in the vicinity of Norilsk, near the mouth of Russia’s Yenisei River, faulty storage and small-scale pipeline leaks have routinely discharged oil and natural gas into northern soil and northern waters for decades, most egregiously in Western Siberia and Russia’s Yamal Peninsula, but in North America as well.

The earth-shaping effects of mining are particularly scarring to landscapes like the Arctic’s, and cleanup of mine tailings and other contamination has never been adequate. Communities in the north also produce everyday garbage, the proper disposal of which is more difficult in such remote locales.

The mushroom growth of high northern military facilities during World War II and the Cold War exacerbated this problem. Many parts of the Arctic metamorphosed into armed camps and factory towns as air bases, submarine pens, navy dockyards, and missile launch centers sprang up around the circumpolar periphery.

A crew from the Red Army's Northern Fleet heading for Kirkenes in 1944.

Home to the USSR’s Northern Fleet and the crucial ports of Murmansk and Arkhangelsk, the Kola Peninsula and its waters offshore became a dumping ground for spent fuel and toxic waste, including nuclear material “stored” in Andreeva Bay. Kamchatka and Chukotka, in Siberia’s far northeast, projected Soviet military power in the Pacific but left environmental damage outlasting the Soviet Union.

American military outposts inflicted similar ecological stress—not just in Alaska, but in Iceland and Greenland, which hosted the Keflavik and Thule air bases—as did NORAD radar stations administered throughout the north by Canada and the United States. All of these have left behind the decades-long effects of fuel exhaust, leaching and rusting metal, and discarded plastics, long after the Cold War’s end.

And this is to say nothing of radioactivity.

One potential disaster was barely contained in January 1968, when an American B-52 bomber, carrying four thermonuclear devices, crash-landed on the Greenland ice not far from Thule. Although no blast occurred, one bomb sank into the ocean and three square miles of ground were irradiated.

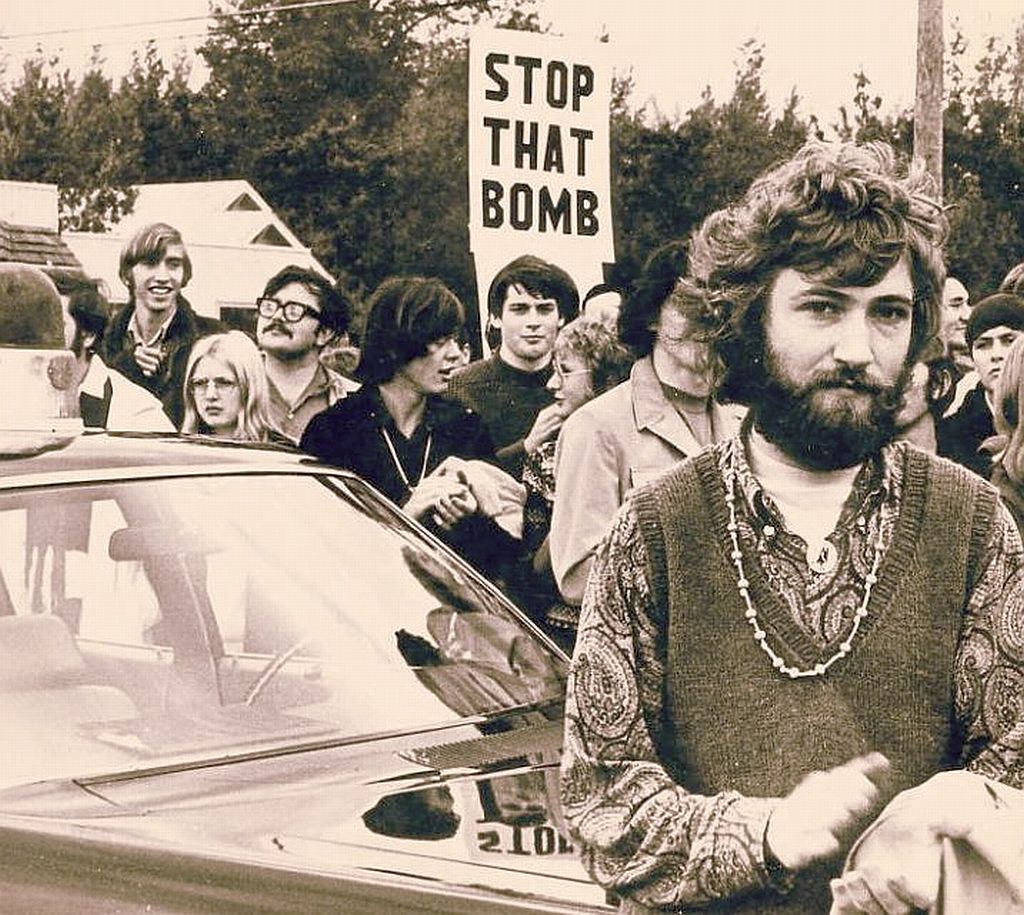

A 1965 Greenpeace protest calling for action against the nuclear testing on Amchitka Island, Alaska.

More deliberate damage was inflicted on the Aleutian island of Amchitka, site of three atomic bomb tests between 1965 and 1971. The third of these remains the largest underground A-test in U.S. history, sparking the protest movement that led to the founding of Greenpeace.

Displacing hundreds of native Nenets, the USSR carried out some 200 atomic tests on the Novaya Zemlya archipelago separating the Kara and Barents seas. The “Tsar-Bomba”—the largest atomic device ever detonated in human history—exploded there in October 1961.

This was humanity’s way of repaying the welcome the Arctic had earlier offered.

Icelandic-Canadian explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson, one of the era’s most enthusiastic modernizers, had spoken of a “Friendly Arctic” where “the torch of science” would “light the way to civilization.” But already in the late 1800s and early 1900s, polar explorers and scientists were noting signs of the warming that we now call climate change.

Vilhjalmur Stefansson and his ice party leaving Collinson Point, Alaska, 1914.

In the 1920s and 1930s, some of the first glaciologists to provide empirical evidence of the high north’s warming—among them Vladimir Vize of the USSR, Norway’s Adolf Hoel, and Hans Ahlmann, famous in Sweden as “Professor Ice”—presented their findings in a spirit of optimism, reasoning that milder temperatures meant greater potential for technological and economic development.

Not every step led in this direction, and certain moments in the decades following World War II helped to slow or limit the harm inflicted on the region. The postwar era has seen native populations regain some measure of political and economic agency, as witnessed by the formation of the Inuit Circumpolar Council in 1977; the creation of Sami parliaments in Finland, Norway, and Sweden in the 1970s and 1980s; and the1999 establishment of Nunavut as Canada’s newest territory.

Even in Russia, where the hideous aftereffects of Stalin’s collectivization of northern hunting, fishing, and herding—which, among other things, killed a quarter of the USSR’s domesticated reindeer—lingered for decades, native Siberians began advocating for themselves by joining the Inuit Circumpolar Council and founding their own Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North.

Plenary of the inaugural Sámi Parliament in 1989.

In many cases, Arctic natives have managed to assert land rights, halt harmful projects, and win fair compensation for natural resources.

Examples include the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act in 1971 and the campaign by Canada’s Committee for Original Peoples’ Entitlement to stymie construction of the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline. Although ultimately futile, opposition in the 1970s to Norway’s Alta-Kautokeino hydroelectric complex, which disrupted reindeer migration routes, galvanized Sami political activism for years to come.

More broadly, environmental activists have scored some important victories. The frightful thinning of the ozone layer over the North and South Poles was reversed in large part by crusades to eliminate CFCs in the 1990s. International accords in the 1970s and 1980s dramatically curtailed the slaughter of whales, seals, walruses, and other sea mammals inhabiting the high north.

By the 1980s and 1990s, the climate-change clarion call penetrated the public sphere. NASA astrophysicist James Hansen’s 1988 testimony before the U.S. Senate, Al Gore’s 1992 Earth in the Balance, the 1997 Kyoto Protocol—all these gave hope that serious commitments to halt and even roll back environmental wreckage, both globally and in the Arctic specifically, would take permanent hold.

Trapped in a Vicious Cycle

Unfortunately for the Arctic, momentum has continued to favor the forces of overdevelopment, now unmistakably in the ascendant. In a bitter irony, Arctic warming makes the region more accessible, stimulating new levels of eagerness to take advantage of it, whether by moving freight along Russia’s northern coastline or through Canada’s increasingly navigable Northwest Passage, or by tapping into its enticingly large pockets of petroleum and natural gas.

More human activity leads to more warming, enabling even more human activity—to the short-term profit of some but to the planet’s long-term detriment (to say nothing of possible geopolitical impacts if a militarized “scramble for the Arctic” breaks out over development rights and sovereignty).

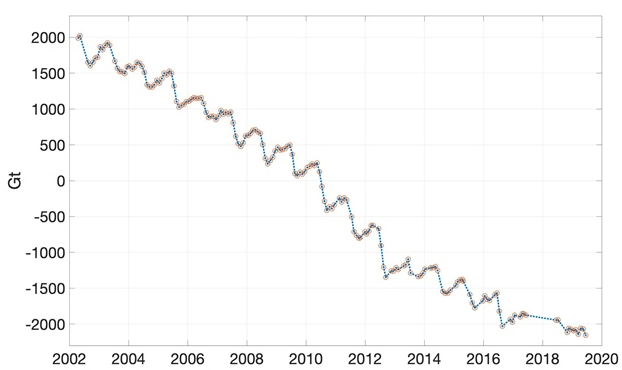

Worse yet, this cycle operates indirectly and insidiously over vast distances. Greenhouse gas emissions worldwide contribute to the precipitous melting of the Arctic pack ice, which has helped regulate the planet’s temperature for millennia by reflecting sunlight back into space. In 2018, the Norwegian Polar Institute reported that the extent of Arctic sea ice that summer had shrunk by almost half a million square miles compared to 20th-century norms.

This spring, the American Geophysical Union issued a dismal prediction that, even if carbon-control efforts meet the most optimistic expectations in years to come, the Arctic will completely lose its summertime ice cover. The thinning of Arctic ice is no longer just the result of climate change, but one of its accelerants. Open water in the north absorbs more of the sun’s heat, making the planet warmer, causing more ice to melt, exposing more water, and so on every year.

Nor is the extent of the problem yet realized, for the same vicious cycle influences other constituents of the northern ecosystem. The receding of Arctic glaciers everywhere has become practically visible to the naked eye in real time.

In August 2020, the eventual eradication of the Greenland ice cap—which not only further reduces the high north’s sunlight-reflecting capacity, but is projected to contribute mightily to rising ocean levels worldwide—was declared all but unavoidable by a team of glaciologists in Nature: Communications Earth and Environment.

The disintegration of permafrost in Canada and especially Siberia threatens to release immense quantities of long-frozen methane into the atmosphere and make the planet even hotter. Permafrost destabilization also weakens human-built structures throughout the north, helping to cause this summer’s catastrophic diesel fuel spill near Norilsk—a discharge rivaling that of the Exxon Valdez debacle three decades ago.

Finally, diminished snowfall has been linked to the drying out of northern soil and the exposure of highly flammable peat deposits, a key factor in the wildfires that have plagued Arctic landscapes since 2016 and that blanketed Siberia this summer and last with smoke clouds larger than the European Union.

The Arctic is Closer Than You Think

Not all readers may be overly alarmed to hear this. After all, the most immediate victims will be circumpolar communities, most of them tiny, all of them located far from the population centers of the south, and animal species that, however iconic, are anything but central to most people’s modern existence. How much will any given individual miss the polar bear—or the narwhal, the caribou, and the walrus?

A painting of Walruses by C. E. Swan, 1909.

But the polar worlds are not as distant as we might think, and, to paraphrase Leon Trotsky (at least possibly), while you may not be interested in the Arctic, the Arctic is interested in you.

When the melting of Greenland adds to rising sea levels, coastal cities from Miami to Jakarta will feel it. If the thawing of Arctic pack ice alters the temperature and salinity of the Atlantic basin, key oceanic currents such as the life-giving Gulf Stream could be diverted.

Not only will softening permafrost lose its ability to sequester greenhouse gases, it will likely permit the escape of pathogens and other dangerous substances that have been locked away for centuries.

A 300m long slump caused by thawing permafrost at the Noatak National Preserve in Alaska, 2004.

Rising temperatures in the north have weakened the “Arctic fence”—the system of wind currents that normally confine the hemisphere’s coldest air to the highest latitudes—extending the so-called “polar vortex” southward and, according to many scientists, contributing to recent weather extremes in the south, including the merciless “superstorms” that have lately begun to pound seaboards in the United States and elsewhere.

As weather events and geophysical anomalies that feel more appropriate to the Book of Revelation than to the pages of Science or National Geographic continue to manifest themselves with depressing regularity, more and more of them will prove to have originated in the Arctic.

All of these factors make the Arctic not some distant realm, but a global backyard. Reversing the environmental damage we have caused there would be difficult enough, even had bold action been taken years ago.

It has become all the more daunting a task, thanks to the retrograde actions of too many of today’s corporate and political leaders, among them Vladimir Putin, with his aggressive drive to maximize the settlement and economic exploitation of Russia’s Arctic territories, and Donald Trump, with his stunning withdrawal from the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change and his reckless decision to open up the Alaska National Wildlife Refuge to oil and gas development.

It is all the more urgent now to care about what we are doing to the Arctic—not only for its sake, but also for our own. Our capacity to kill entire ecosystems has grown exponentially. But we too easily forget that the Arctic can hurt us if we continue to hurt it. In that very real sense, Arcticide is nothing less than suicide.

Anderson, Alun. After the Ice: Life, Death, and Geopolitics in the New Arctic. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian, 2009.

Berton, Pierre. The Arctic Grail. Toronto: Viking, 1988.

Hall, Sam. The Fourth World: The Heritage of the Arctic and Its Destruction. New York: Knopf, 1987.

Krupnik, Igor, et al., Northern Ethnographic Landscapes: Perspectives from Circumpolar Nations. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian, 2004.

Lopez, Barry. Arctic Dreams. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1986.

McCannon, John. A History of the Arctic. London: Reaktion, 2012.

McGhee, Robert. The Last Imaginary Place: A Human History of the Arctic. Toronto: Key Porter, 2005.

Nuttall, Mark, et al., ed. The Routledge Handbook of the Polar Region. London: Routledge, 2018.

Officer, Charles, and Jake Page. A Fabulous Kingdom: The Exploration of the Arctic. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Wheeler, Sara, Magnetic North: Notes from the Arctic Circle. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011.