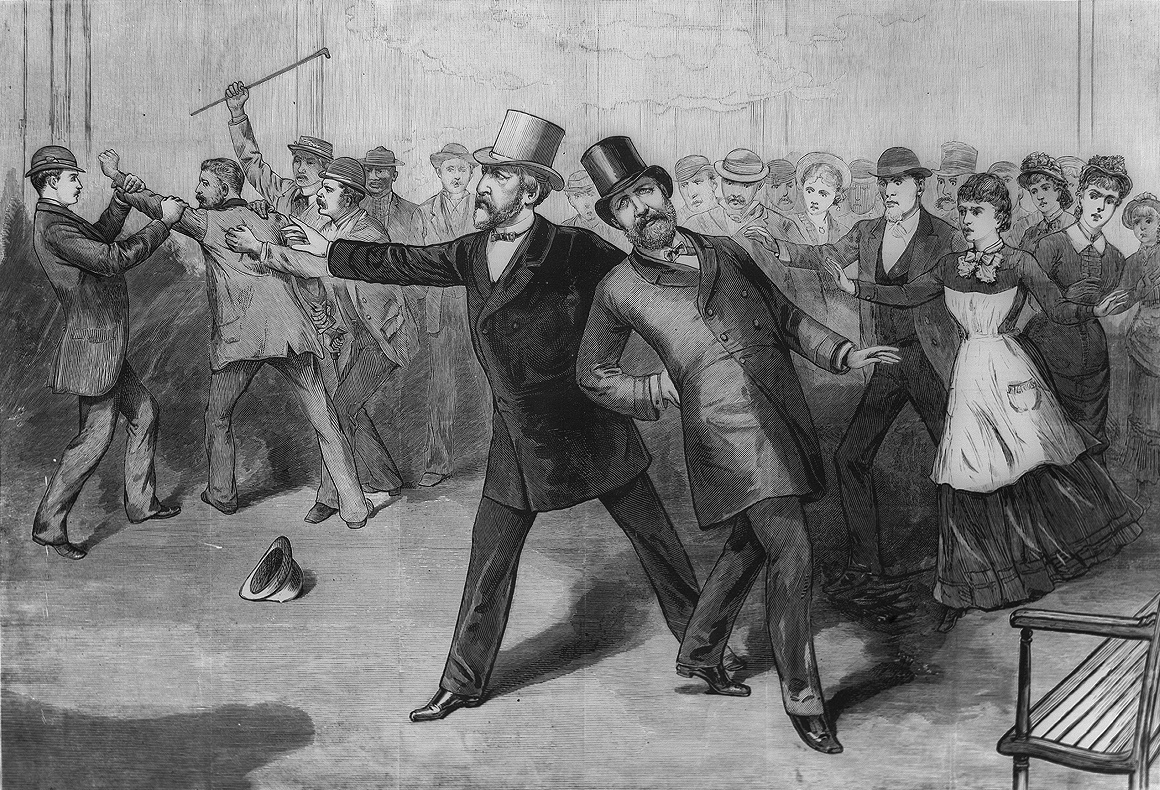

On July 2, 1881, President James A. Garfield entered a railroad station in Washington, D.C. After a hectic first four months in office, he looked forward to taking the train to the New Jersey seashore. There he would join his wife, Lucretia, and their children for a well-earned vacation. As the president made his way to the train, chatting companionably with Secretary of State James G. Blaine, a man moved suddenly towards them, pulled a gun, and shot Garfield twice in the back.

One bullet wounded him only slightly in the arm, but the other buried itself deep in his lower back. There it resisted all efforts by his physician, Dr. Bliss, to find and remove it. In the process of probing for the bullet, Dr. Bliss likely introduced infection which ravaged Garfield’s body for two and half months. Surrounded by his family, he died on September 19, 1881, plunging the entire nation into mourning.

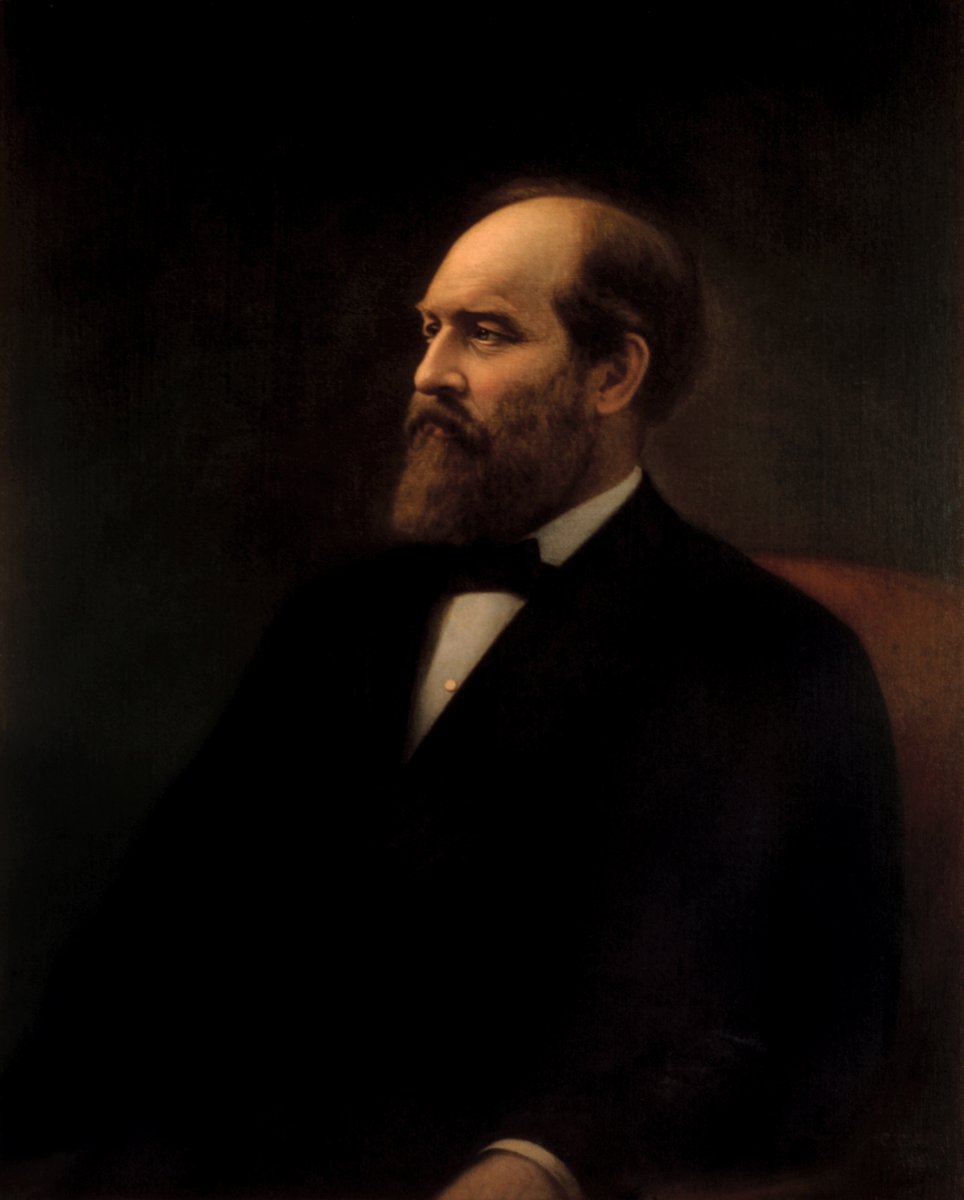

Garfield had been well-liked, and the ups and downs of his long illness, reported in papers across the country, evoked deep sympathy for him and his family. Their outrage led Americans to ask questions. Who was this man who had shot the President? Why had he done it? As lawyers, psychologists, and reporters delved further into the mind of the assassin, Charles Guiteau, they found that the answer lay with Guiteau’s own mental instability, intensified by political strife within a deeply divided Republican Party.

|

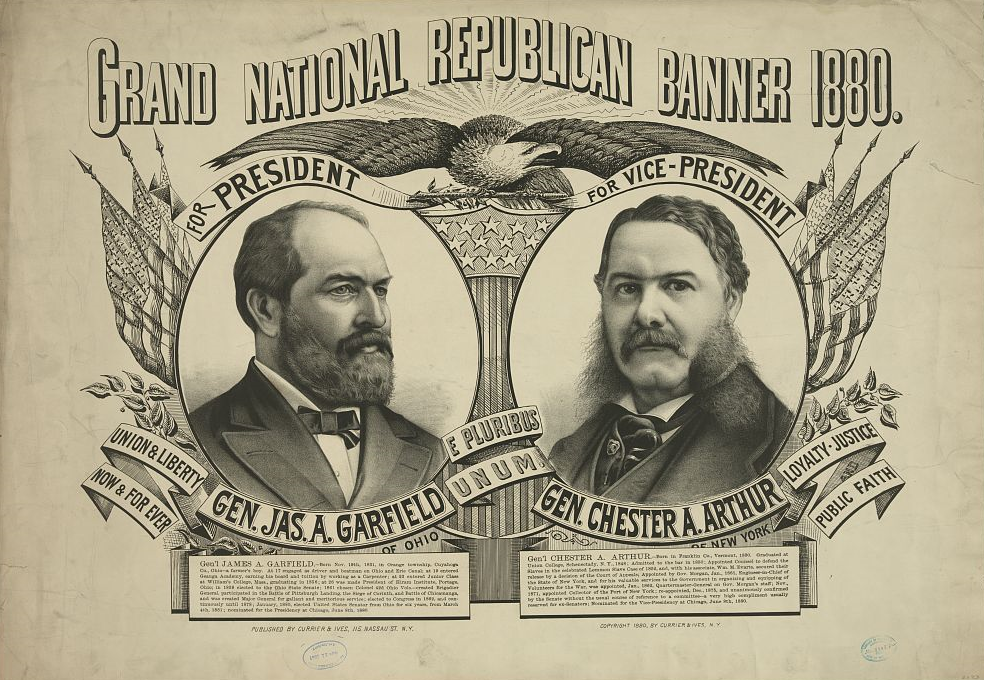

The contentious state of the Republican Party in 1880, the year before Garfield’s assassination, will sound familiar to anyone following the present political situation this election year. A powerful segment of the party, called the Stalwarts and led by Roscoe Conkling, supported the nomination of former president Ulysses S. Grant. Dismayed by the corruption that had run rampant through Grant’s administration, others refused even to consider Grant’s candidacy and lobbied for James G. Blaine or John Sherman to receive the nomination. When convention delegates deadlocked on ballot after ballot, Congressman and Senator-Elect Garfield emerged as a compromise candidate, ultimately winning the nomination on the 36th ballot.

Although party leaders agreed to support Garfield for president, the convention did not mark the end of party strife. After Garfield won the presidency, division between the Stalwarts and the rest of the party deepened. For much of the nineteenth century, the political party that won the presidency had the opportunity to fill tens of thousands of government positions with their supporters—an arrangement known as the spoils system. Conkling expected Garfield to allow him to fill the most lucrative positions with his followers. When Garfield refused, the courteous relationship between the two men burst into open conflict.

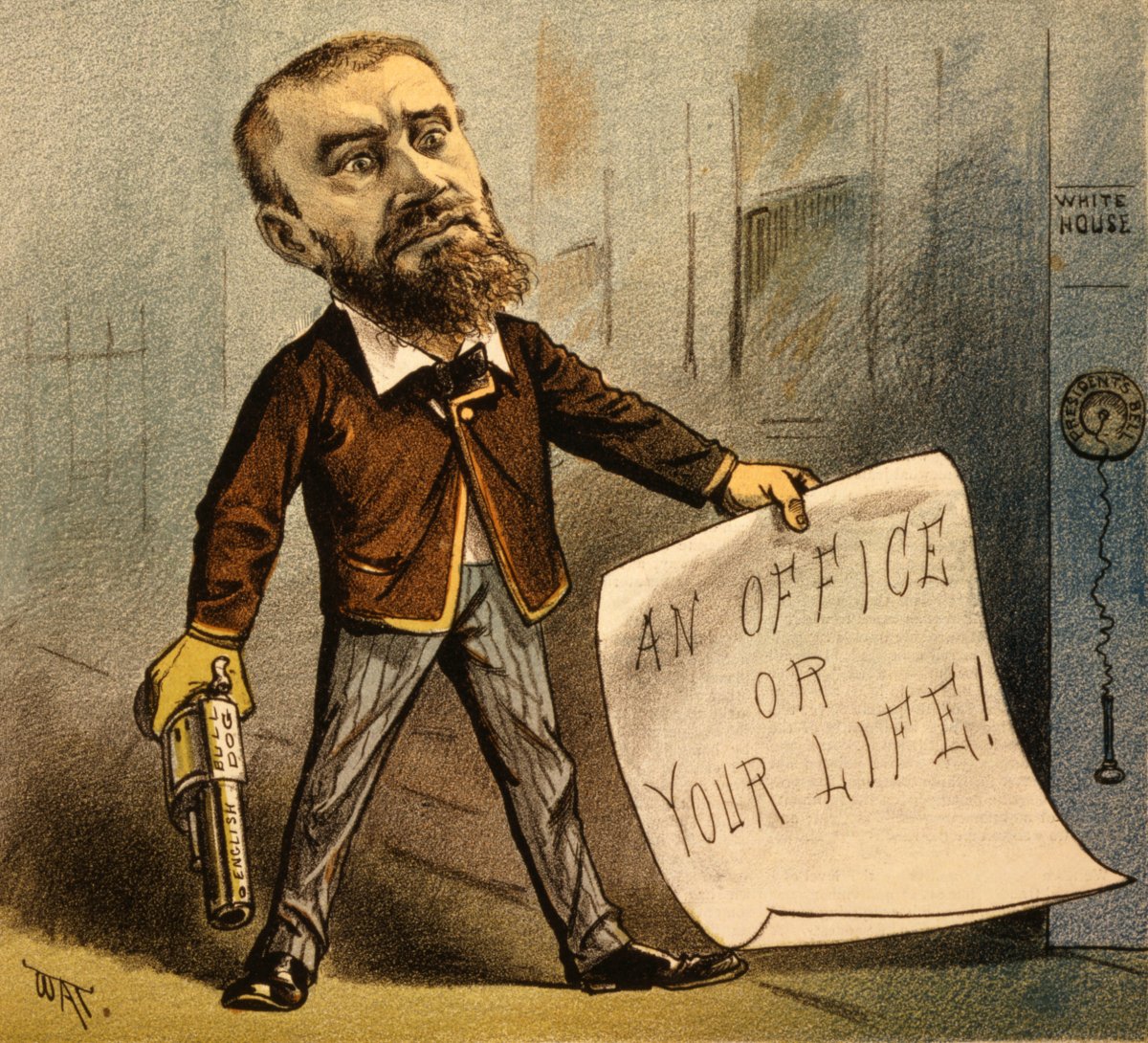

Enter Charles Guiteau. Guiteau was a political hopeful with absolutely no qualifications or experience except a series of failed business and journalistic ventures. He had written a speech in support of Garfield during the campaign and believed that he deserved an appointment to an important diplomatic post. He haunted the halls of the White House for weeks, even managing to meet Garfield once face-to- face. But the diplomatic post never materialized.

As Guiteau waited, he read the newspapers, which prominently featured the conflict between Garfield and Conkling. Already mentally unbalanced, Guiteau convinced himself that the country would erupt into another civil war unless Garfield were removed from office. He also came to believe that God had commanded him to kill the president. Guiteau bought an ivory-handled pistol and began to stalk the president, finally pulling the trigger at the train station on July 2.

After the shooting, Guiteau told the police, “I did it. I will go to jail for it. I am a Stalwart, and Arthur will be president.” In a document that he had prepared in advance to justify his actions, Guiteau had written, “The President’s tragic death was a sad necessity, but it will unite the Republican party and save the Republic… I had no ill will towards the President. His death was a political necessity.”

After the President’s death in September, Guiteau’s case came to trial. Since he had admitted to the crime, there was no question about whether or not he had shot the President. Instead, the trial sought to answer the question of whether Guiteau was guilty of murder as indicted or not guilty by reason of insanity.

Experts from the newly emerging professional field of psychology took the stand, some testifying to Guiteau’s sanity, and others to his insanity. Guiteau himself even sought to act as his own defense attorney, still believing that he could justify his crime to the American people. But the jury would have none of it. They judged Guiteau guilty as indicted, and he was hanged almost a year to the day after the shooting of Garfield.

Garfield’s assassination and Guiteau’s subsequent trial highlighted several issues in the midst of transition in late nineteenth-century American society. In 1881, ideas about germ theory and the importance of antisepsis had been circulating in the medical world. But, to Garfield’s detriment, many American doctors, including Dr. Bliss, did not subscribe to them.

In addition to faulting Bliss for his negligent care of Garfield, many Americans blamed the spoils system for Garfield’s shooting. His death rallied support for civil service reform, leading to the passage of the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act of 1883.

Yet one theme at the crux of the political turmoil surrounding Garfield’s assassination does not seem to have disappeared. Division within political parties still remains characteristic of American politics, evident in this election year now more than ever.