Today, Ludlow, Colorado is a ghost town. Like so many other small mining towns that sprung up during the mining boom of the Second Industrial Revolution, it had helped power the stunning growth of the world's largest industrial economy. Eventually, the coal was used up, and the town simply became no more.

Ludlow, however, has more than its share of ghosts. It is the site of the deadliest labor war in American history.

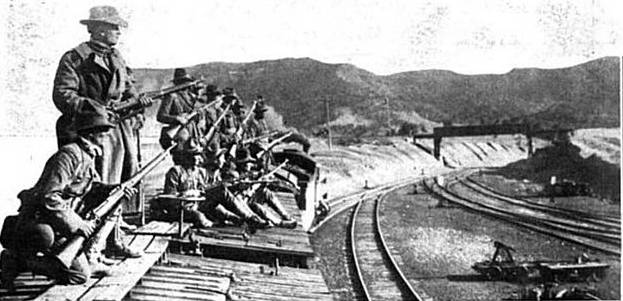

Since the autumn of 1913, Ludlow miners (pictured above in 1914) had struck for union recognition; the company's obedience to Colorado's 8-hour day law; the right to live outside of company houses; an end to being paid in scrip (money only good at company stores); and the elimination of various other abuses common to company towns of the period. For them, meaningful collective bargaining could deliver a fair day's pay for a fair day's work, not to mention a measure of dignity for those men that earned their bread in the darkness underground.

On April 20th, 1914, Colorado state militiamen attacked a massive tent colony erected by striking miners and their families who had been evicted from their company homes, killing eighteen of them, including women and children. The attack sparked a pitched battle. Between September 1913 and the end of April 1914, 75-100 people were killed and dozens more injured and jailed.

The massacre sparked a public relations crisis for John Rockefeller Jr., the owner of the largest mining company in the state, and convinced Congress to launch an investigation into industrial conditions. Nevertheless, by the end of 1914, the strike had been completely broken.

One hundred years later, as the gap between the wealthiest and the poorest Americans grows, as news reports announce the decline, or death, of the middle class, as “class warfare” is trumpeted by politicians and pundits, as “right to work” legislation is repeatedly introduced to state legislatures, and as the fight to increase the minimum wage gears up, the massacre at Ludlow reminds us that class conflict has deep roots in American history.

During the Gilded Age, class divisions were an unmistakable fact in American life. From the Lower East Side of Manhattan to the cotton fields of Alabama to the treacherous mines of Colorado, tens of millions of Americans toiled under extreme conditions to earn meager wages in order to build the American industrial colossus. Meanwhile, corporate businessmen controlled their business empires from opulent boardrooms on Park Avenue. Even the nascent middle class of college-educated professionals lived in relative comfort.

What people called the “Labor Question” was the burning issue of the day. Could a free nation such as the United States long tolerate such extreme inequality? Contemporary jurist, and later Supreme Court Justice, Louis Brandeis remarked, “We can either have democracy in this country or we can have great wealth concentrated in the hands of the few, but we can't have both.”

“Which Side Are You On,” a song inspired by a coal miner strike in Kentucky, described a society that was all too familiar for American workers: “They say in Harlan County, there are no neutrals there. You'll either be a union man, or a thug for J.H. Blair [Harlan County Sheriff].” In a time when the cost of rights in the workplace could be measured on the obituary page and class identity ran deep, it was clear which side you were on.

In the 1930s, the United Mine Workers (UMW)—the same union that failed to bring mine owners to the bargaining table in Ludlow—would launch the Congress of Industrial Organizations (the CIO), the most successful and dynamic labor organization the nation had ever seen. When it merged with the American Federation of Labor (the AFL) in 1955, the combined labor federation had organized both skilled workers and much of America's mass production industry.

In postwar America, workers gained unprecedented influence. They were electing governors and presidents rather than getting shot at by militiamen. Labor, in short, had found a seat at the table, though often a junior one compared to capital and the state.

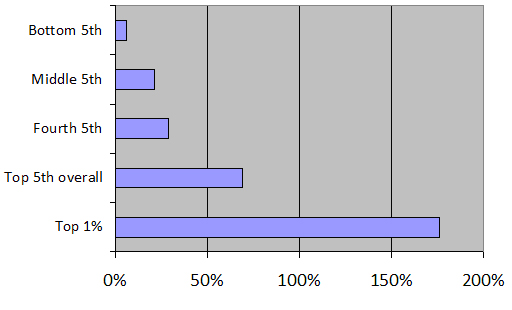

Over the last 35 years, however, the loss of manufacturing jobs, a variety of new laws making it harder for workers to unionize, and the rightward drift of the American political center have greatly diminished the power of organized labor in America. Wages for American workers have stagnated or contracted, and income inequality in recent years has reached 1920s levels.

In fact, the American working class hasn't truly recovered from the recession of the 1970s and appears to have lost the ability to articulate its own identity and class needs. Since that period, wage inequality and consumer debt have gone up; secure, high-wage employment and union membership have declined.

Yet, despite the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression, there is little evidence that American workers have the same fighting spirit as their predecessors in Ludlow. Those miners fought, suffered, and died believing they could build a better world together. That world has not yet come to be. The rise of the CIO out of the misery of the 1930s stands perhaps as a lesson for our time. It may be that despair and opportunity are not so far apart.

The ghosts of Ludlow remain.