Once a fringe legal theory, “originalism” now dominates on the U.S. Supreme Court, shaping the Court’s most recent and most controversial decisions. This month, legal historian Saul Cornell explains what originalism is, where it came from, and why most Constitutional historians find it deeply problematic.

Once the most respected branch of the federal government, the Supreme Court’s approval ratings have reached an all-time low, approaching the abysmal view most Americans have of Congress.

The authority of the courts depends on the belief that judges are acting in a neutral, apolitical, and impartial manner. Although “originalism” was once thought to be the best way for the court to achieve that goal, this controversial theory now contributes to the court’s credibility problem and is not the solution to it.

Currently, the U.S. Supreme Court is dominated by “originalists.” Many of the blockbuster decisions in Spring 2022 relied on this controversial theory to strike down long-standing precedents and laws.

In Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health (2022), the Supreme Court cast aside the Roe v. Wade (1973) decision that has been the law of the land for a half a century. New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen, another landmark decision decided during the 2022 term, struck down a century-old New York gun law. In other cases, dealing with executive power and the rights of criminal defendants, the high court took a chainsaw to hack through a thicket of established precedents.

Although originalists claim they are simply restoring the purity of the original constitution, the theory and practice of originalism at the Supreme Court suggest otherwise. The new and unprecedented originalist constitution being fashioned by the current court is a not rooted in history and has little connection to the historical text it purports to honor.

Given that Americans are likely to be living under a newly created “originalist Constitution” for some time, it is worth asking some basic questions about this theory. What is originalism? Where did it come from? Is it a good or workable theory of constitutional interpretation? What connection, if any, exists between the originalist constitution and the historical document sitting under glass at the National Archives?

What is Originalism?

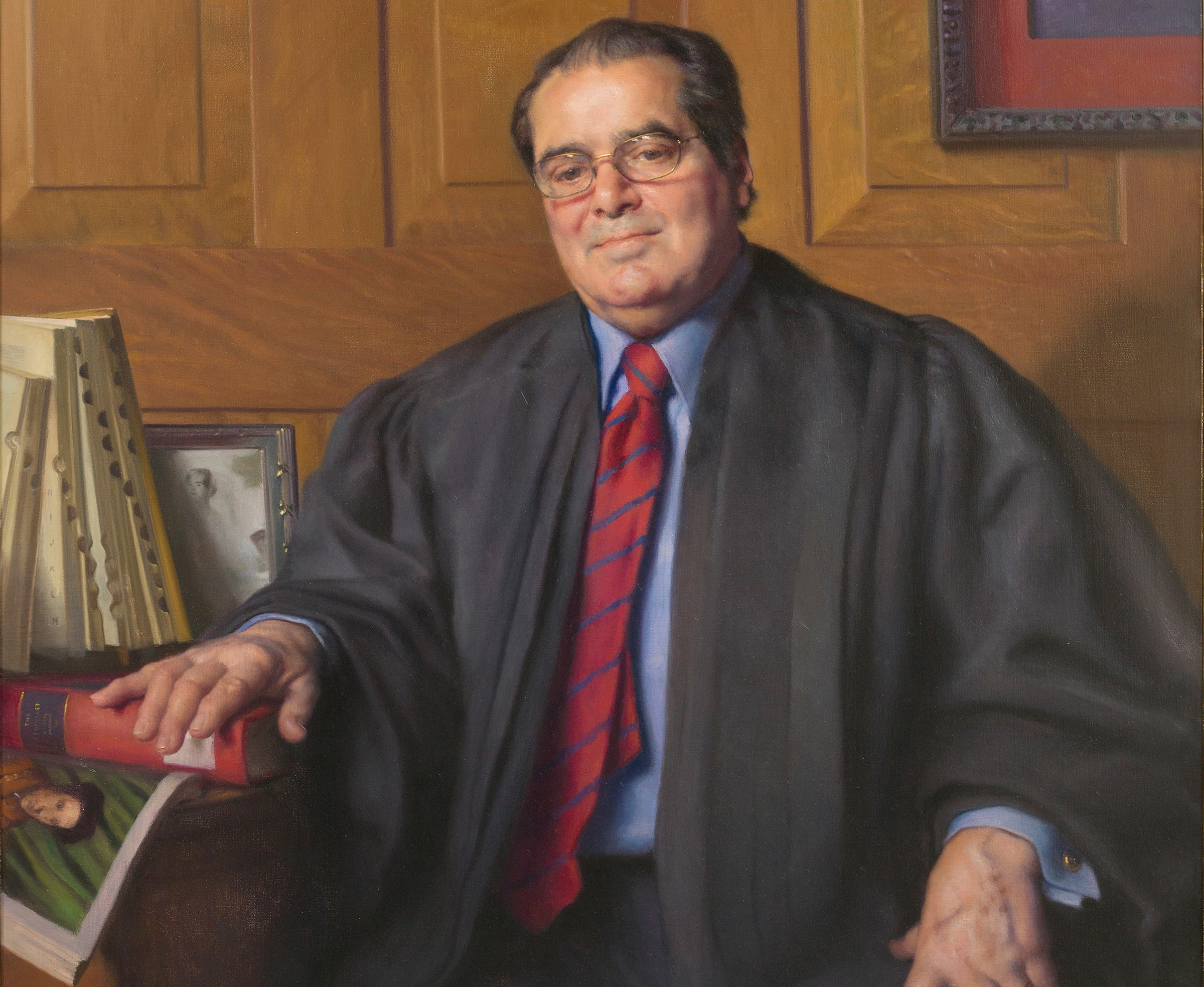

Justice Antonin Scalia, champion of originalism, famously said that we do not have a living constitution, but a dead one. Scalia’s often-quoted quip was aimed at those who favor the notion that the Constitution’s meaning is not frozen but should evolve and change. Scalia believed that the meaning of the text had been fixed at the time of its adoption.

The dominant form of originalism now is “public meaning originalism.” According to this theory, the meaning of the Constitution is to be gleaned from the original public meaning of its words as they would have been understood in the eighteenth century.

Some parts of the Constitution are written with precise meaning: each state gets two Senators. Not much room for disagreement in this instance. But other provisions of the text are abstract or ambiguous. What do the words “necessary and proper” mean? What does “freedom of the press” mean?

Historians focus on what the words meant in the past, not what they mean to us today. In that regard, originalism and history are in accord. For example, the Constitution requires the federal government to defend the states against invasion and “domestic violence.”

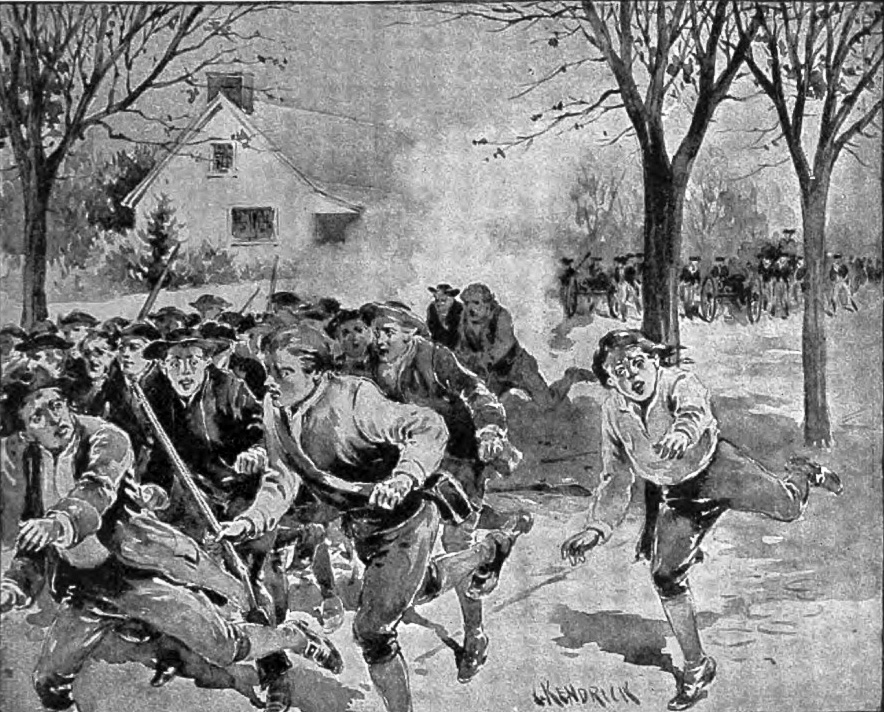

The Founders were thinking of popular uprisings such as Shays’ Rebellion, an agrarian insurrection that rocked Massachusetts in the late 1700s. Although the term domestic violence now typically means violence among family members or intimate partners, few jurists would argue that the Constitution allows the President to send in troops to settle a violent marital dispute.

Of course, interpreting a constitution is different from what historians do when they make sense of other old legal documents, such as wills, contracts, or statutes. Nor can one simply run the text of the Constitution through something like a Google translator function: a fact most originalists have failed to grasp.

Words, particularly the words of a constitution, are embedded in a rich range of contexts when they are uttered. Recovering their original meaning requires restoring not just the text but paying close attention to the contexts in which those words would have been interpreted.

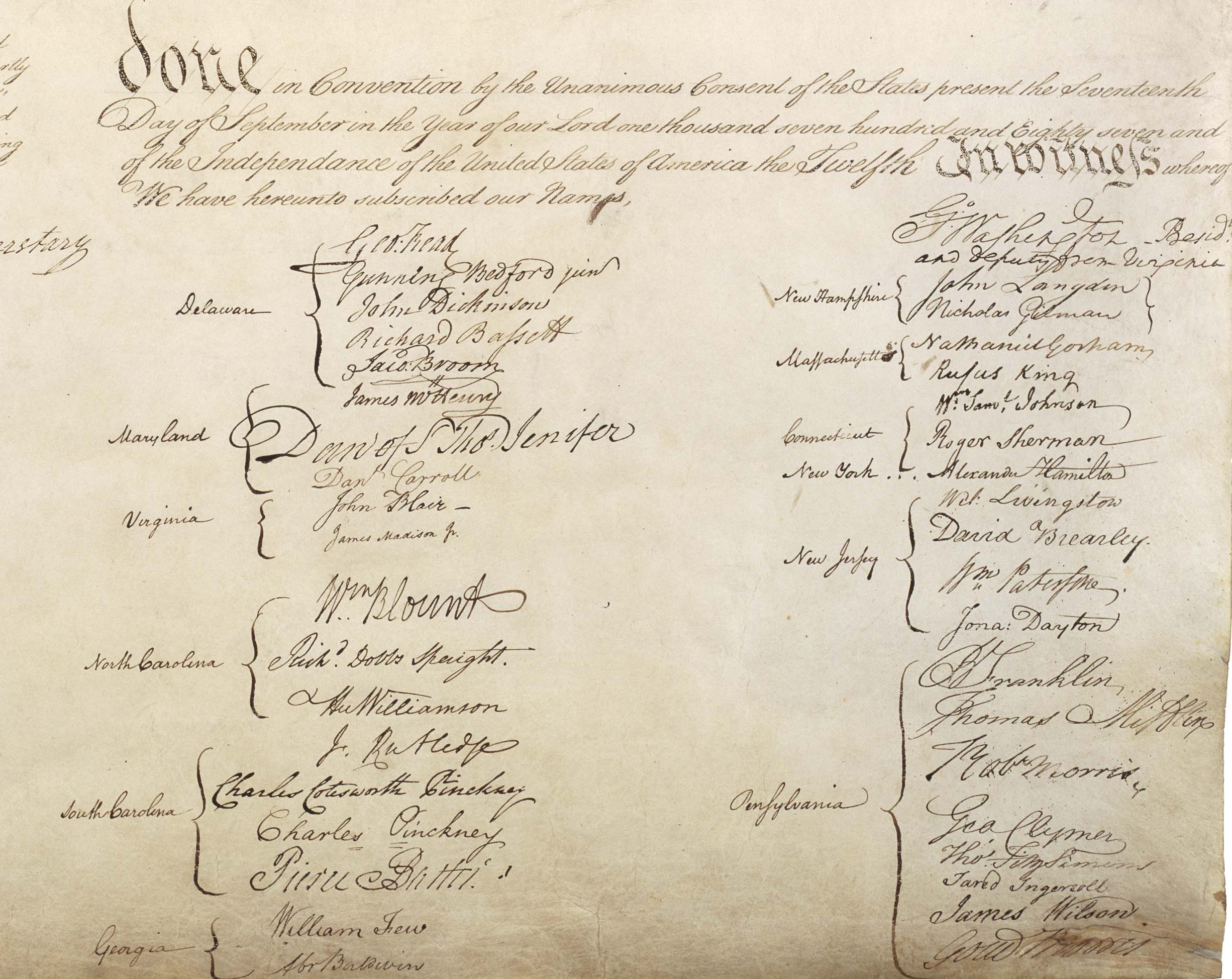

In contrast to those other more familiar legal texts, the U.S. Constitution was the product of a collective effort, so discerning a single intent as a guide to its meaning is hard to do, if not impossible. Additionally, from the moment it was adopted, there were bitter disagreements over what type of text the Constitution was and how it ought to be interpreted.

The Constitution was a new type of document with no clear precedents or agreed-upon methods for interpreting its meaning. Was the Constitution like a Parliamentary statute, or more like a contract between the people and their government? The former uses one set of legal principles and the latter a different set of tools.

Within months of its adoption, former Anti-Federalists—opponents of the unamended Constitution—and Federalists were already arguing bitterly over what the text meant. Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, two of the co-authors of The Federalist, the contemporary commentary on the Constitution they published, disagreed over almost every major constitutional question that emerged during the turbulent decade after ratification. If people at the time could not agree on a single meaning of the text, it seems unlikely that judges in the 21st century can find one.

Other originalists have argued that the Constitution should be read like a recipe that needs to be followed precisely as one would in cooking a meal. Originalists, however, don’t appear to have spent much time in the kitchen. Real cooks seldom follow recipes strictly and any cook worth their salt would adjust a recipe on the fly to deal with the actual situation they faced in the kitchen. If you opted for a tough cut of meat, such as brisket, you would certainly opt to cook the stew a bit longer. Speaking of salt, most recipes typically end with the advice “season to taste,” so different cooks are likely to interpret that advice in light of their own experiences in the kitchen and distinct culinary traditions.

If the entire Constitution contained precise instructions, the recipe analogy might work better. But most parts of the text are not precise at all. Much of the document was deliberately crafted with open-ended language, both to allow the government to address unprecedented challenges and because compromise during the drafting of the document meant using ambiguity and vagueness in a strategic fashion, kicking many practical questions down the road to later generations.

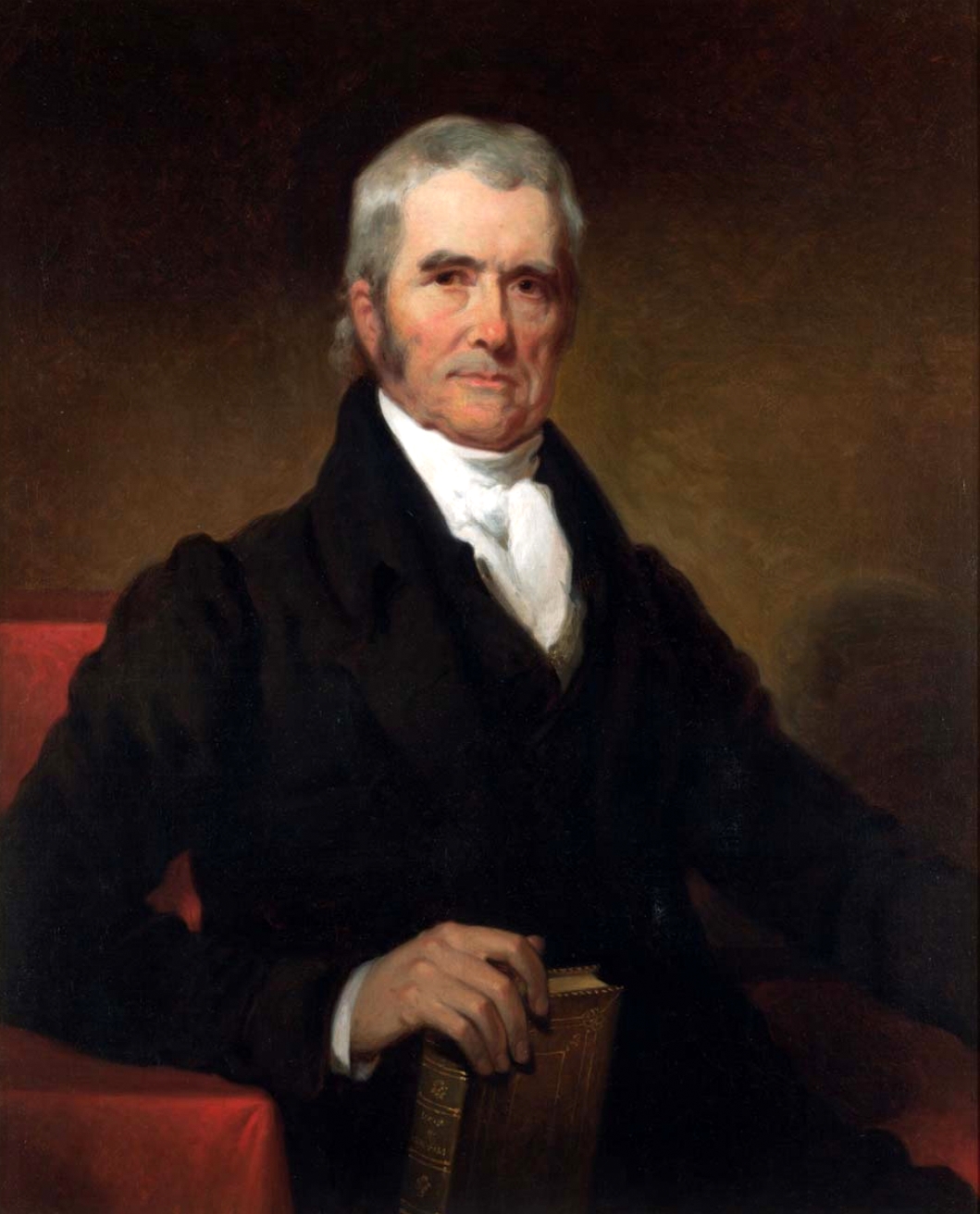

John Marshall arguably the most significant Supreme Court Justice in American history, wrote that a constitution detailing all aspects of a government “would probably never be understood by the public.” In contrast to laws that can run on for pages, a constitution is different:

“Its nature, therefore, requires that only its great outlines should be marked, its important objects designated, and the minor ingredients which compose those objects be deduced from the nature of the objects themselves. That this idea was entertained by the framers of the American Constitution is not only to be inferred from the nature of the instrument, but from the language.”

Marshall recognized that the Constitution’s text by itself, only about four pages long, could not contain the entire meaning of the new frame of government adopted by the people in 1788.

Most of the provisions likely to be at issue when a case reaches the Supreme Court contain language that is open to interpretation. Thus historians, in contrast to originalists, believe the effort to find a single clear meaning for many constitutional provisions is an illusionary quest. The best one might hope to achieve given this fact is to take sides in the debates that Hamilton, Madison, and other Americans engaged in more than two centuries ago.

To get around this obvious historical problem, many originalists have argued that their theory does not seek to find the subjective views of any individual interpreter, but the objective meaning the words would have communicated at the time.

Thus, the goal is not to find what Hamilton or Madison thought the Constitution meant, but what the reasonable person, or typical reader of the text, at that time thought the words meant. The problem with this approach is it assumes the existence of a consensus about constitutional meaning and interpretation in 1788, another claim that most historians of the period reject.

In practice, the typical reader conjured up by originalists seems to read the Constitution in a way that invariably aligns perfectly with the modern Republican. In its current form, originalism is little more than an act of historical ventriloquism in which judges project their policy preferences, consciously or unconsciously, on to historical actor and texts. Put another way, originalism turns out to be little more than right-wing living constitutionalism dressed up in silk stockings and britches.

Consider a contentious issue that deeply divides Americans today: the meaning and scope of the right to keep and bear arms.

Originalists would argue that it does not matter that elite Federalist merchants and the back-country farmers in Massachusetts who took up arms during Shays’ Rebellion each understood this right in radically different ways. The fact that both sides communicated with each other meant that they agreed on the meaning of the words in the Constitution’s text. But the fact that people communicate does not mean they always understand one another and it certainly does not mean they agree with one another.

Most historians would find such a claim dubious. The fact Massachusetts put down the rebellion suggests that the Shaysites’ views were not universally admired or emulated, certainly not by the mercantile elite.

Where did Originalism Come From?

The conventional historical account of originalism traces the movement to the Presidency of Ronald Reagan (1981-1989), when conservatives began to critique the modern rights revolution inaugurated by the Warren Court (1953-1969). In this version of the story, originalism emerged as a response to the decisions of the Supreme Court that strayed too far from the original text and in essence created new rights—such as the right to privacy—not explicitly articulated in the text.

The Warren Court has become synonymous with an expansion of individual rights. The landmark desegregation decision Brown v. Board of Education was a product of the Warren Court as was Loving v. Virginia (1967), the case that struck down laws prohibiting inter-racial marriage.

One of the most contentious decisions of the Warren Court prohibited school prayer. And, Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), the case vindicating privacy rights, including access to contraception, helped anchor an entire line of cases protecting unenumerated rights, and laid the foundation for rulings on abortion and gay marriage.

Conservative critics of the Warren Court including conservative Barry Goldwater fulminated against Brown, claiming it misrepresented the intent of the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment who never intended to desegregate public schools.

Originalism continues to be plagued by a “Brown problem.” The consensus among legal academics is that Brown was correctly decided. But despite heroic and elaborate efforts to show that there is an originalist foundation for Brown, many scholars reluctantly concede that Goldwater was correct that the original Fourteenth Amendment does not support Brown.

Faced with this fact, most legal scholars argue that originalism is clearly a flawed theory that offers modern Americans a constitutional vision tainted by racism. Brown is the foundation for our multi-cultural and inclusive vision of contemporary American democracy and for any constitutional theory to succeed in modern America it needs to vindicate Brown, something originalism has not accomplished despite multiple attempts.

If the first incarnation of originalism (Originalism 1.0) that emerged during the Reagan years aimed to curb the excesses of activist judges, the second iteration of originalism, the New Originalism (Originalism 2.0) spearheaded by Antonin Scalia, appointed to the Court in 1986, sought to empower the court.

In contrast to Originalism 1.0, Scalia and his New Originalist supporters framed their theory when there was a narrow right-wing majority on the Supreme Court. Originalism 2.0 was developed to give right-wing judges tools to roll back the excesses of the Warren Court and the New Deal.

Originalism 2.0 became the creed and playbook of the Federalist Society, an influential cadre of lawyers who functioned as a farm-team for lawyers, judges, and legal academics eager to turn back the constitutional clock to an imaginary moment in the nation’s past that never actually existed. Together with a vast originalist industrial complex composed of other right wing thinks, the NRA, and other interest groups originalists sponsored conferences and created networking opportunities for those eager to foment a constitutional counter revolution.

By the time of Donald Trump’s election and with the help of a reliable pipeline for dependable judicial candidates vetted by the Federalist Society, numerous originalist judges were appointed at all levels of the federal judiciary, and crucially, originalists now dominate the Supreme Court.

The agenda of the new originalist majority on the Supreme Court is to severely limit federal power, particularly the authority of the modern administrative state. In addition to the decision overturning Roe v. Wade, originalist arguments have also been used to expand the rights of corporations to contribute to elections and limit government’s ability to regulate industry to fight climate change. In the case of guns, the agenda is the opposite, to limit states and localities from regulating guns. Conservatives once supported federalism across the board, now originalists only support it when it advances their policy objectives.

Is Originalism the Only Way to Use History? Common Law Constitutionalism

Originalists prefer to see things in simple, dichotomous terms. Either one supports originalism or one favors a living constitution. For the latter, the Constitution ought to be read so that the text is understood in such a way that it keeps up with changes in society.

Describing American law as a choice between a dead constitution and a living one ignores the vast middle ground in constitutional theory, most importantly: common law constitutionalism. This position is much more popular among American law professors than originalism. A variant of it has also dominated American law for most of its history.

Common law constitutionalism starts with the historical text (what the Constitution meant in the eighteenth-century) but it also gives considerable weight to how courts have interpreted its meaning over time—the weight of judicial precedent.

Finally, common law constitutionalists care less about how the law was applied 200 years ago and care more about how the general principles embodied in the text ought to be applied to current challenges. We are bound by the principles in the text, not the specific application of those principles 200 years ago.

Common law constitutionalism recognizes that history did not come to abrupt end the year the Constitution was adopted, and though the theory does not attract much media attention, it enjoys broad support among serious scholars who argue that it not only accounts for how the Constitution has been interpreted over the long arc of American history, but it produces better outcomes.

Long usage, in effect, sanctifies the decisions of earlier courts and silently incorporates them into our constitutional tradition. If precedent rests on a demonstrable error, common law constitutionalism embraces moderation and minimalism. If the decisions of courts have drifted away from the accepted meaning of the text at the time the text was created (assuming such a meaning is discernible in the first place) then judges ought to build on that legacy and not prune it away seeking to restore the primitive purity of the original text.

The right of privacy is a good example of how common law constitutionalism has functioned. The word privacy does not appear in the original constitution but our right to it was created by the courts in the 20th century. In the decision overruling Roe v. Wade, Justice Alito argued that abortion has no anchor in the text of the Constitution. But neither does the right of privacy.

By judicial sleight of hand, Alito tried to distinguish why some made up rights ought to be protected (such as privacy), but others eliminated (abortion). He argued that the Court had no desire to cut away the branch of constitutional law that has affirmed a right of privacy. But, saying that you have no desire to undo a precedent does not state a constitutional principle, it merely states a constitutional prejudice or preference.

Alito also argued problematically that the case of contraception is unlike abortion because there is no other life at stake. But several forms of contraception act by inducing abortions. Additionally, carrying a baby to term is not without serious risks for many, including death. So, despite efforts to erase the realities of pregnancy, Alito’s argument rests on more smoke and mirrors.

Ironically, Clarence Thomas, the court’s most outspoken originalist was far more intellectually honest and rigorous in his concurrence in Dobbs, writing that if abortion is not constitutionally protected then neither are contraception, or gay marriage. (Thomas did not include inter-racial marriage in his critique, but the precedent protecting it also rests on unenumerated rights such as privacy.)

Consider this analogy to understand the wisdom of the common law approach: Imagine you construct a ship from a blueprint and set sail. While at sea you encounter numerous unforeseen structural problems and must fix the ship with materials available on board. Back in port for repairs, would you seek to restore the ship to its original design flaws and all, or would you attempt to make it seaworthy again by incorporating some of the changes that had proved effective while on your journey?

Historians v. Originalists

Historians did not engage much with the second, new iteration of originalism when it first emerged. Thus, historians ceded the field of constitutional study to political scientists and law professors. Although entering the debate over originalism 2.0 belatedly, a few trenchant historical critiques of the latest variant of originalism have started to coalesce.

One obvious problem with the newest version of originalism is that it has delivered major victories to the Republican Party and few comparable outcomes for those in the center or on the left. A genuinely neutral theory would generate results that did not coincide so neatly with the political agenda of the party that appointed originalist judges.

Originalism also depends on a sophisticated understanding of American history, which few judges or lawyers seem to possess. This often leads them to make serious errors and distort the meaning of the texts they claim support their view of the Constitution.

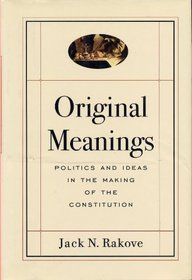

Originalists often engage in pseudo-historical analysis disparagingly dubbed “law office history.” Historian Jack Rakove, in his Pulitzer Prize winning study, Original Meanings (1996), argued that originalists lacked a neutral method to sum up the multiple conflicting intents of the different actors responsible for framing and enacting the Constitution. Without that, they simply cherry pick evidence that suits their ideological agendas.

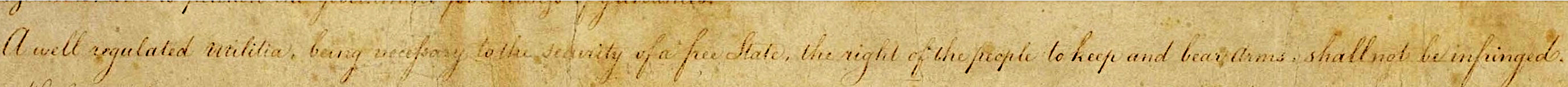

The Supreme Court’s three landmark originalist cases on guns illustrates this problem well. In 2008 the Supreme Court decided District of Columbia v. Heller, a case that tossed aside almost 70 years of precedent holding that the Second Amendment only protected weapons that were suitable for militia service and that were used to further the aims of a well-regulated militia.

Writing for a narrow majority, Justice Scalia argued that the Second Amendment protected an individual right of self-defense that had no necessary connection to participation in an organized militia. Scalia read the Second Amendment backwards, setting aside the text’s preamble that clearly referenced a well-regulated militia and focusing instead on the clause affirming the right to keep and bear arms.

In Scalia’s view the preamble did not state the purpose of the Amendment, but one of many purposes, so that part of the text should not control how the right was construed. He defended the decision as the greatest exemplar of originalism in the court’s history.

In a blistering dissent, Justice John Paul Stevens, pointed out that no American court had ever read a text in this fashion and he reminded Scalia and others in the majority that a basic rule of legal interpretation required that one give effect to the entire text, not just the parts one likes.

The Ironies of Originalism

In an influential Harvard Law Review article (1984), legal scholar H. Jefferson Powell argued that the Founding generation were not themselves originalists. In particular, Powell argued that the framers of the Constitution did not believe that their intent should guide future generations’ interpretations. In other words, the “original” intent of the framers was to treat the Constitution as fluid not frozen, living not dead.

Far from being a return to what the framers had in mind when they wrote and debated the meaning of the Constitution, originalism represents a radical break from American legal history.

Appealing to history, originalists often ignore or misconstrue that past they claim support their interpretations. Despite repeated protestations that their method is neutral, originalist decisions have consistently supported a very particular political point of view. Once confined to the fringes, originalism is reshaping American life and will likely do so for years to come.

Jonathan Gienapp, Constitutional Originalism and History, Process: A Blog for American History, March 20, 2017,

Ilan Wurman, The Founders Originalism National Affairs 2022

Keith E. Whittington, Originalism: A Critical Introduction, 82 Fordham Law Review 375 (2013).

Michael Dorf, The Undead Constitution 125 Harvard Law Review 2011 (2012)

Jack M., Balkin, Lawyers and Historians Argue about the Constitution 35 Constitutional Commentary 1209 (2020).

Saul Cornell, Originalism As Thin Description: An Interdisciplinary Critique, 84 Fordham Law Review Res Gestae 1 (2015).