White nationalists and American Neo-Nazis want the rest of us to see them as legitimate social and political movements, rather than as the violent hate-groups and conspiracy theorists that they are. By refusing to condemn the white supremacist violence in Charlottesville, VA in August 2017, President Donald Trump helped those groups move toward that goal. But among the most peculiar aspects of this desire to become mainstream is the way these groups have appropriated the history of Greece and Rome as part of their genealogy. This month classicist Denise McCoskey unpacks the relationship between the classical world and the world of white supremacy.

The deadly violence that took place in Charlottesville, VA in August 2017 might seem a long way away from ancient Athens.

But for several years now, those of us who study the ancient world have become progressively aware that American Neo-Nazis, white supremacists, and others affiliated with the so-called “alt-right” are employing the symbols of the classical world as a way of legitimating their outlandish claims.

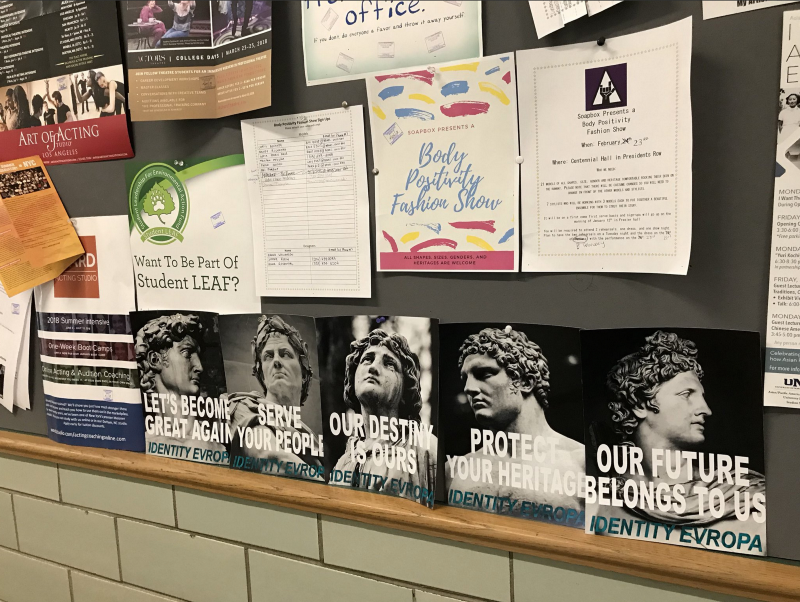

A 2018 Identity Evropa propaganda poster featuring Michelangelo’s statue of David in front of a fallen replica of the statue on the campus of California State University, Fullerton [Image via Twitter].

From marble statuary employed by the white nationalist group Identity Evropa to the prominent display of the Parthenon on the website of the Neo-Nazi forum Stormfront, classical texts and classical artwork are being increasingly used as a shorthand for claims of white supremacy. (At the same time, white supremacist groups have also been recruiting at unprecedented levels on college campuses.)

Even before Charlottesville, a number of classical scholars had already gotten involved in high profile confrontations with the alt-right. Donna Zuckerberg, editor of the online publication Eidolon, which seeks to explore the intersections between classics and contemporary society and culture, first raised the alarm in a column in November 2016.

In June 2017, Sarah Bond, an assistant professor of classics at the University of Iowa, was bombarded with hate mail after her online article about classical statuary was picked up by Campus Reform and other conservative outlets.

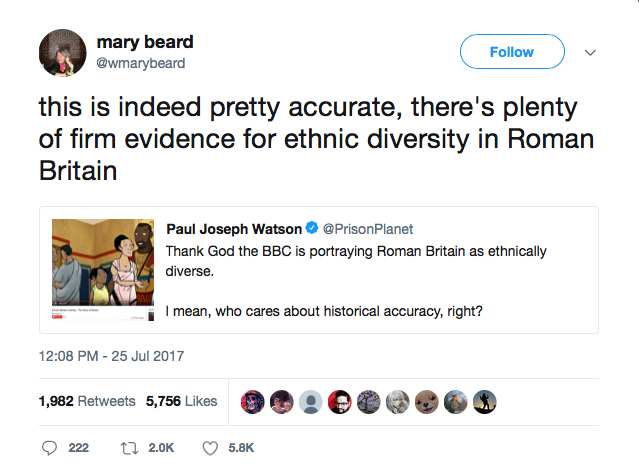

Some weeks later, British classicist Mary Beard got her own share of trolling after defending the BBC’s use of a black-skinned character in a short cartoon about Roman Britain. Nor was the “dumpster summer of racism” confined to classics alone as medieval historians, too, found themselves increasingly forced to challenge white supremacist appropriations of their field.

White supremacist protesters in Charlottesville, VA in August 2017 carrying Identity Evropa flags.

So alarming were these incidents that an entire website specifically devoted to documenting and refuting the appropriation of classical antiquity by hate groups has now been initiated.

But even as classical historians are working harder than ever to debunk the use of classical history by today’s white nationalists, we are swimming against a tradition that stretches back centuries.

The Allure of “Greekness”

The desire to establish an affiliation with the “Greeks,” particularly with the ancient city-state of Athens, dates almost as far back as the height of Athens itself in the fifth century B.C.E.

A statue of the Athenian orator Isocrates in a garden in Versailles, France.

As he engineered his own rise onto the world stage, Alexander the Great carefully cultivated a version of Greek culture that was becoming more standardized—one based on Athenian norms.The role of Athenian culture in defining the source and alleged superiority of “Greekness” had already been advanced around 380 B.C.E., when the Athenian orator Isocrates, touting the virtues of his city, proclaimed that students in Athens had become the teachers of the rest of the world. He insisted that “Greek” itself no longer connoted a race, but an “intellect” or “state of mind” (dianoia) and that those called “Greek” shared an “education” or “training” (paideia) rather than common blood.

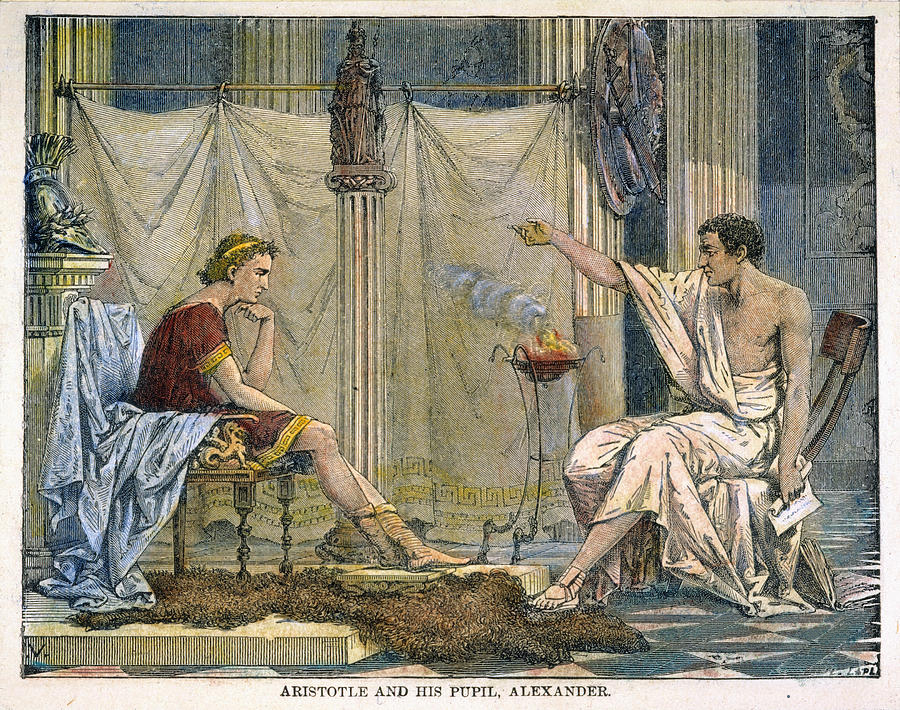

Thus, not only was Alexander famously tutored by the philosopher Aristotle, but he also apparently spoke a form of Attic Greek (or koine) in public, a fact revealed by the historian Plutarch when he noted that the young commander, in a moment of great anger, once accidentally blurted out in “Macedonian.”

Speaking Greek presumably allowed Alexander to assert his bona fides in a Greek world that remained skeptical of those savages from the hinterland of Macedonia—even as his father, Philip, had already conquered a coalition of Greek city-states, including Athens, in 338 B.C.E.

The Romans, of course, would eventually assume control of the ancient Mediterranean, and their engagement with Greek culture remained both deep and, at times, conflicted. As the poet Horace famously intoned: conquered Greece had captured her fierce conqueror.

An 1866 French engraving of the philosopher Aristotle tutoring Alexander the Great.

Although the culture of classical antiquity largely went dark during the Middle Ages, its rediscovery helped fuel the vibrant visual and textual culture of the Renaissance and, eventually, the notion of a tangible Greco-Roman “inheritance” would be promoted throughout Western Europe and the United States via the invented concept of “Western Civilization.”

Greece and Rome Cross the Atlantic

The desire to claim a classical inheritance had a formative role in America from its earliest period. For, among a broad range of ideas and practices, the Greeks and Romans have ostensibly taught Americans how to design our public architecture, how to conceive of arts and literature and, relatedly, how to define taste and beauty, how to conceptualize personal virtues like reason and self-restraint, and even how to organize our government politically: in short, how to articulate many of the fundamental principles of American self and nationhood.

Just as important as public buildings built in the “neo-classical” style, knowledge of classical culture—literature, political theory, philosophy—was seen as necessary in 18th- and 19th-century America. The experiment in republican self-government depended on the “virtue” of citizens, so the founders believed, and the best source of virtue was an education in the classics. Not for nothing did sculptor Horatio Greenough portray George Washington, that most virtuous of Americans, dressed in a Roman toga.

The importance of a classical education was not limited to white Americans. African Americans made their own use of the classical past. Frederick Douglass, for example, studied classical oratory closely. And Joseph Wilson, a Black veteran of the Civil War, published a work equating Negro soldiers with those of ancient Greece, The Black Phalanx: A History of the Negro Soldiers of the United States in the Wars of 1775-1812, 1861-’65. By calling units of Black soldiers a “phalanx,” Wilson sought pointedly to portray them as the rightful descendants of the Greek soldier.

Jefferson and Madison, Douglass and Du Bois all believed in the value the Greek and Roman tradition held for all Americans.

Given such a rich range of classical receptions in American life, how did the relationship with ancient Greece become conceived so one-dimensionally as a racial rather than cultural inheritance? How did it become a primal affiliation wielded by some Americans against others rather than a repository of ideas available to us all?

Race before Whiteness

Any equation of Greeks and Romans with whiteness ignores a basic fact: in the world of classical antiquity race did not mean what it does today.

The explanation of what makes people different (and so, also, superior or inferior) was as complex in the ancient world as it is today.

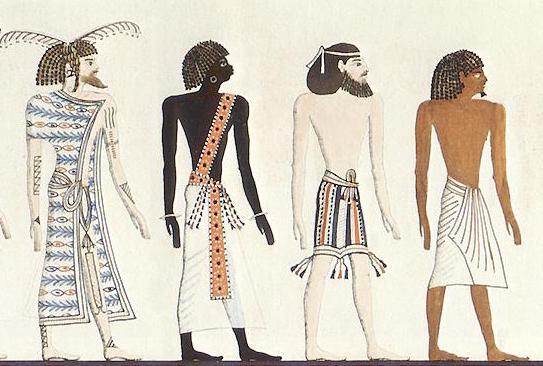

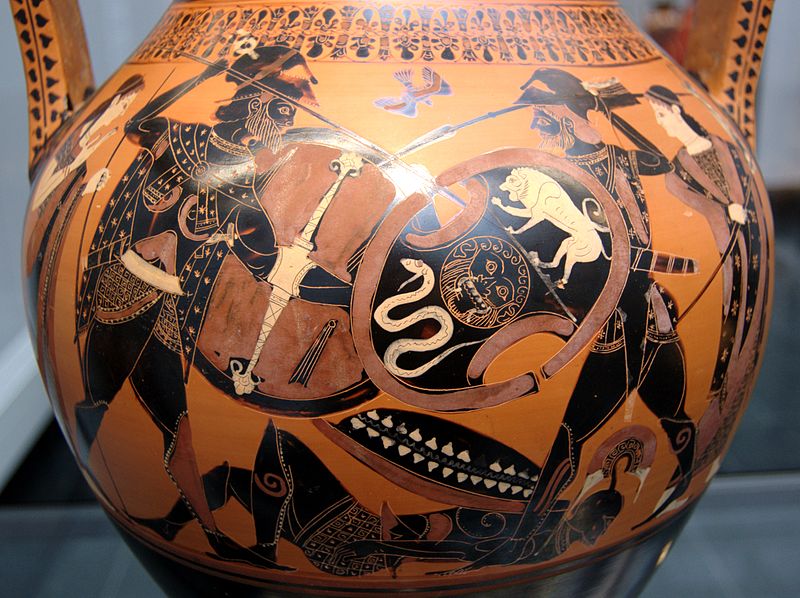

Still, it is clear from our sources that the Greeks certainly did not use skin color to define human variation. Although they used different words to denote a range of skin colors—and depicted different skin tones in art—skin color is represented or mentioned in texts in ways that suggest it is being used primarily to describe physical appearance, without holding further connotations per se.

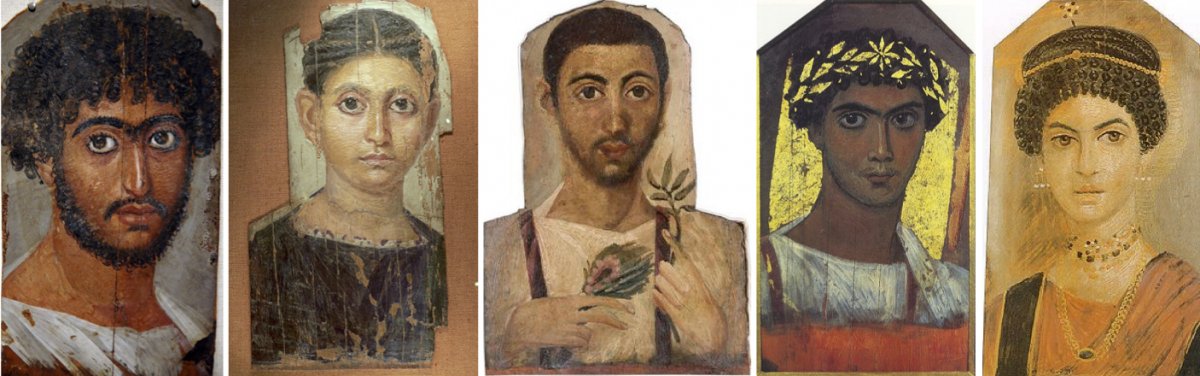

Roman era mummy portraits (first from left, second, third, fourth, fifth).

Moreover, as we can witness on later mummy portraits from the Roman era (art that seems intended to represent real people as closely as possible), the Greeks and Romans themselves had a range of skin colors, as do residents of the Mediterranean today.

Although there is never any indication that the Greeks collectively identified as “white,” there was a group in Greek thought associated with black or dark skin color, the “Ethiopians.” This category was far from consistent in Greek thought, however, and it would evolve over time as the Greeks came into greater contact with Black Africans. In Homer’s poetry, some of our earliest surviving Greek literature, the Ethiopians are portrayed as being especially close to the gods; in one scene Zeus is said to have dined with them.

While they did not consider human variation a product of biology in and of itself, the ancient Greeks did develop a theory that sought to explain human difference through geographic location or the environment. In this view, the climate of a region had a direct correlation with not only a group’s physique but also their behavior and character.

A highly contested 1820 drawing of a fresco in the tomb of Seti I.

Such a theory allowed the Greeks to posit their own superiority by placing themselves in what they considered the best climatic zone (generally speaking, in the center between the various extremes), and also by contrasting Europe with what they called Asia, a territory dominated by the Persian Empire and generally encompassing what is today Turkey and parts of the Near East and Central Asia.

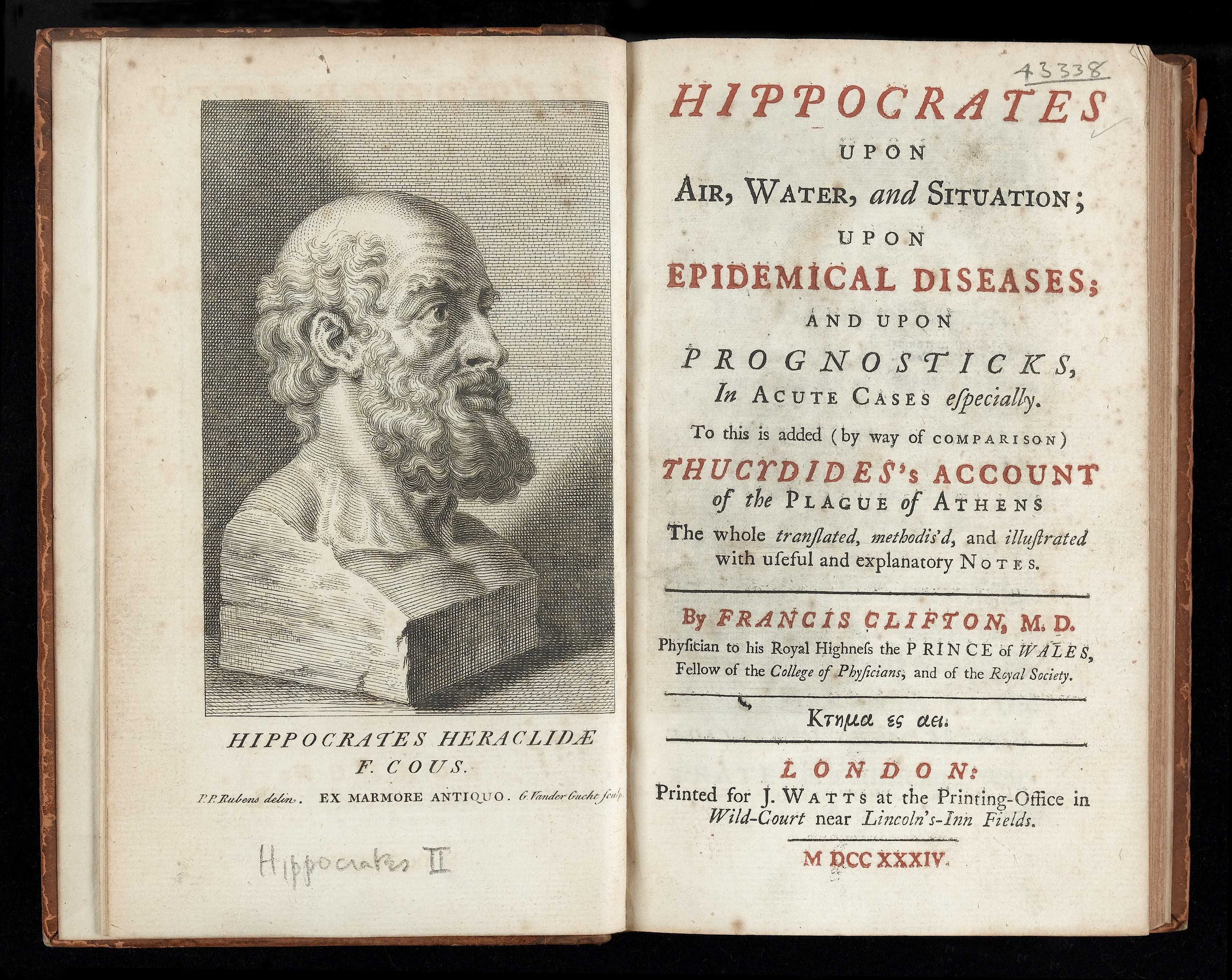

According to the Hippocratic essay, “Airs, Waters, Places,” the most extensive surviving account of ancient environmental theory, because Europeans were subject to greater changes in climate, they were braver and more energetic, while those in Asia, who experienced relatively little change in the weather, were mentally flabby and cowardly.

The title page of Hippocrates's “Airs, Waters, Places.”

But climate did not act alone. Historical events also combined with environmental theory to produce ways of thinking about difference that served more specific uses.

Perhaps most notably, the Persian Wars (499-449 B.C.E.) were a watershed in Greek thinking about themselves and the world around them. Some Greek writers even attributed the astonishing Greek victory over the Persian Empire to “Greekness” itself. According to these writers, the Greeks won because they were racially superior to the Persians.

From there, the Greeks eventually drew a line between themselves and the rest of the world, lumping everyone who wasn’t Greek into the category “barbarians”—a line defined not by skin color, but by a range of factors. A significant feature was the group’s governmental system, differentiating between those living “free” within a democracy and those ruled by a monarch.

Like the Greeks, the Romans never conceived of themselves as “white.”

The Romans did not see the world as a dichotomy between themselves and the “barbarians,” but rather placed other peoples on what we might consider a sliding scale. On that scale, some groups more closely resembled the Roman ideal while other groups were more removed. This enabled the Romans to conceptualize the social complexity they encountered across their vast empire. It allowed some groups to enter the empire peaceably while others were violently subjugated.

So if ancient ideas about race were so different from our own, how did we get so invested in seeing the Greeks and Romans as “dead white men”?

The Whitening of the Classical World

The field of classics itself bears significant responsibility for the whitewashing of classical antiquity.

As a professional practice, classics emerged just as ideas about race were themselves changing. Whereas previously, human variation had been interpreted with the aid of texts such as the Bible, notions of race became increasingly attached to the study of human anatomy throughout the 18th and 19th centuries.

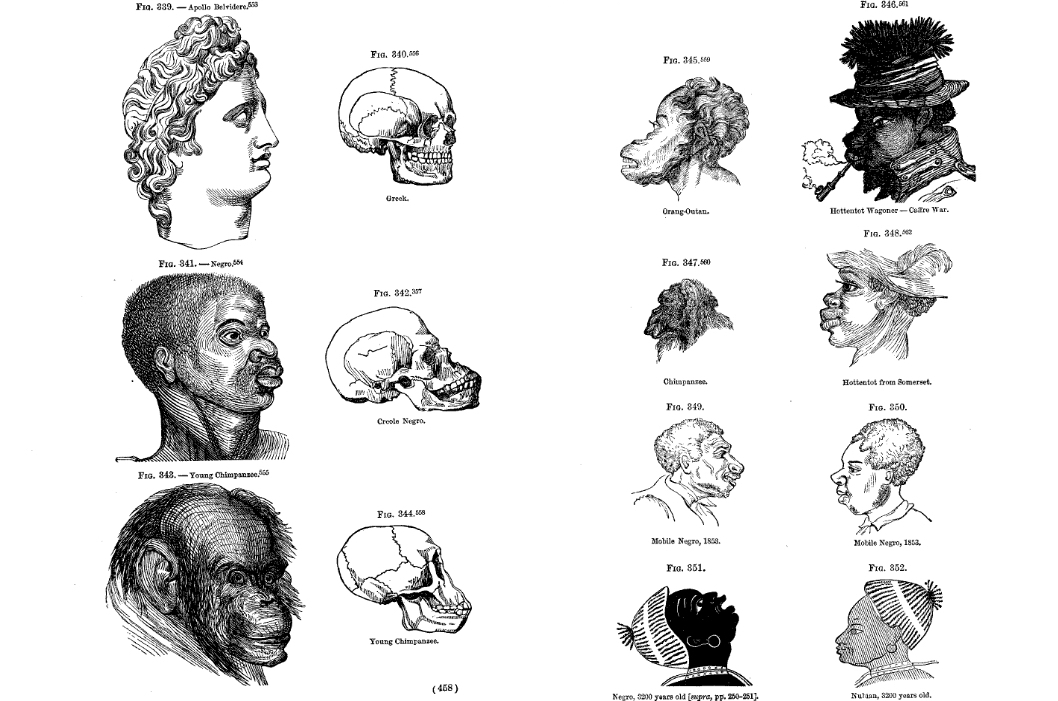

Seeking to account for historical phenomena like colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade, race, and especially skin color, was increasingly treated as a factor of human biology. Across the 19th century, scientific racists measured any number of physical characteristics—from facial features to cranial capacity, hair texture, and the length of limbs—to create racialized hierarchies which invariably landed the Northern European type at the top.

It was during this same period that classical statuary itself began to take on new meaning. Greek and Roman statues now epitomized the physical perfection of the past. By extension, contemporary Northern Europeans and Euro-Americans believed they were the descendants of the ancient Greeks, a belief that, at its most extreme, meant displacing modern Greeks themselves, who had endured Turkish occupation and so were no longer considered “pure” enough to lay claim to such noble ancestry. Such bias still haunts debates today over whether the Elgin Marbles should be returned to Greece.

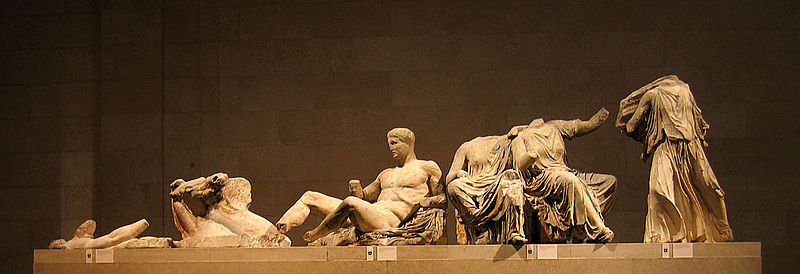

Figures from the East Pediment of the Parthenon from 447-438 B.C.E. in the British Museum.

In using classical sculpture to identify the ancient Greeks racially, 19th -century writers pointed to the whiteness of the marble—though we know now that in antiquity these statues had been painted—and to features such as the angles of facial structure. Thus, the statue of Apollo Belvedere became a particular fixation, its head prominently used in illustrating the superiority of “white” groups on a number of physiognomic charts of the era. The Apollo Belvedere has been seen recently on posters for the white supremacist group Identity Evropa.

Just as the concept of race was fueling new interpretations of science and art history, it was also becoming increasingly central to the writing of history itself. Thus, race increasingly served not simply as an object of historical examination, but as an explanation of historical progress. In this view race is the main engine of human development. Through this logic, it is not just that the Greeks were white, but that they were able to develop their impressive civilization because they were white.

Identity Evropa members placed propaganda posters featuring iconic Classical and Renaissance sculptures like Michelangelo’s David and the Apollo Belvedere on many U.S. campuses in 2017 [Image via Twitter].

In the early part of the 20thcentury, many classical scholars also applied a new racial theory to their interpretations of antiquity: eugenics. A logical outcome of 19th century scientific racism, eugenicists believed that a superior race could be created through the control of human reproduction. Eugenics had its own logical outcome in the Holocaust.

Perhaps most infamously among classicists, Tenney Frank argued in 1916 that “race-mixture” had led to the fall of Rome, a conclusion arising from a set of research questions that barely concealed contemporary anxieties about both the role of former slaves in American society and the rising tide of immigration. Though over a century old, and thoroughly discredited by scholars, Frank’s article is required reading for today’s white supremacists.

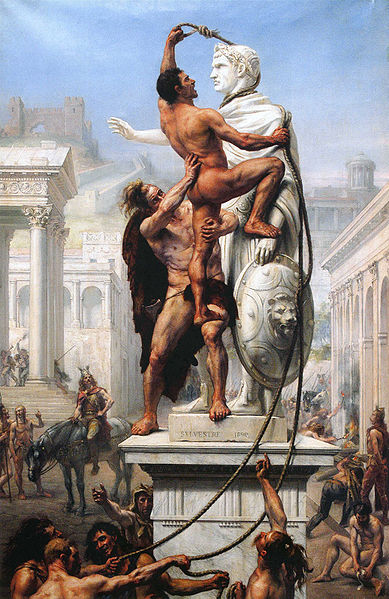

A slide from a Hitler Youth presentation on the supposed origins of Jewish people (left). In 1938, Adolf Hitler went to great lengths to purchase Discobolus, a marble copy of a bronze work by the Greek sculptor Myron of Eleutherae from around 460 B.C.E. (right).

In 1925, classicist John Scott applied the lens of eugenics specifically to the Greek world of Homer. He lamented that in the epic poem the Iliad we could see what he termed “Race-Suicide.” His reading of Homer emphasized the failure of the Greeks to have enough children.

Contrasting the number of children of each of the Greek warriors with Priam’s 50 sons, Scott concluded that “[i]f the Homeric heroes were actually as sterile as they are pictured in Homer it was inevitable that the Achaean civilization should have been submerged under the waves of populous and expanding neighbors,” an interpretation that spoke to contemporary concerns that a general societal decline would take place if the most “fit” people failed to reproduce at the same rate as groups considered inferior.

Of course, worrying about reproductive rates in the Iliad makes about as much sense as worrying about what the characters in the poem “actually” looked like—which has not stopped some people from losing their minds over the casting of a black actor in the role of Achilles in a recent BBC production.

In the postwar era, the whiteness of the Greeks and Romans became simply taken for granted, and the question of race in classical antiquity was focused solely on the question of black skin color, on “blacks in antiquity.”

Such scholarship powerfully demonstrated that black skin color did not mean the same thing in antiquity as it did in the mid-20thcentury, but there was little appetite for unraveling the definition of whiteness in the same way, and the terminology of “race” quietly receded from classical studies.

Race Roars Back in Classics

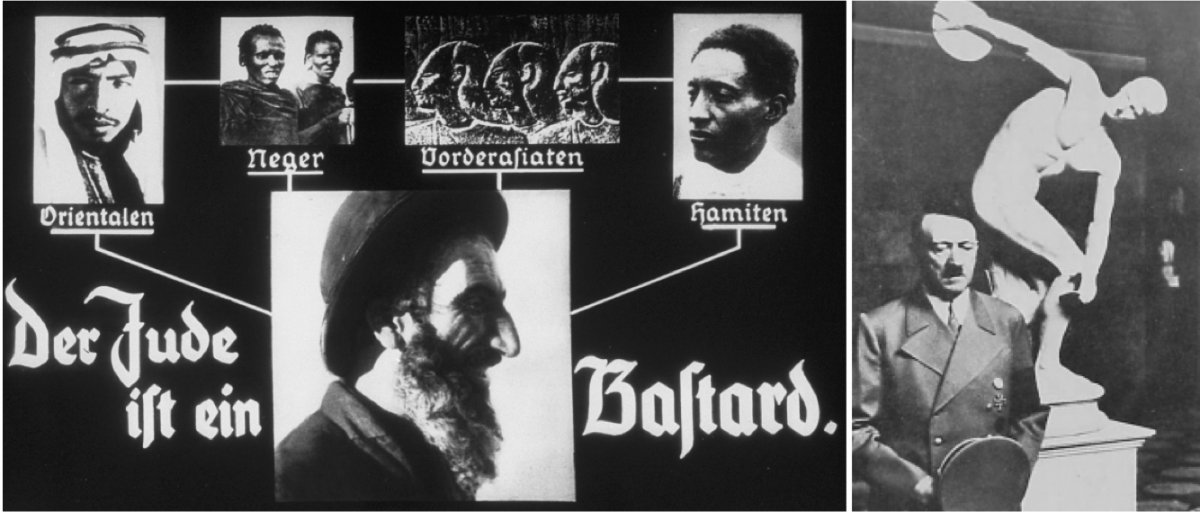

Classicists were soon dramatically forced to confront the racist origins of their own field, however, when Martin Bernal began publishing the controversial multi-volume work Black Athena in 1987.

The first volume of Martin Bernal’s 1987 Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization (left). An advertisement for a 2008 academic conference at the University of Warwick to discuss the issues posed by Bernal’s work on the twentieth anniversary of its publication (right).

In hindsight, the subject of Black Athena is deceptively straightforward; as Bernal wrote: “Black Athena is essentially concerned with the Egyptian and Semitic roles in the formation of Greece in the Middle and Late Bronze Age.”

As Bernal well knew, however, by opening the subject of Greek origins to critical investigation, as well as raising questions about Greek civilization’s putative dependency on cultures to the east, he was unsettling some of the very foundations on which the concept of “Western Civilization” itself had been built. And Black Athena would go on to insinuate that Greek culture was never any “purely” Greek or “western” achievement, but rather a product of the vast social and economic networks traversing the markedly diverse world of the ancient Mediterranean.

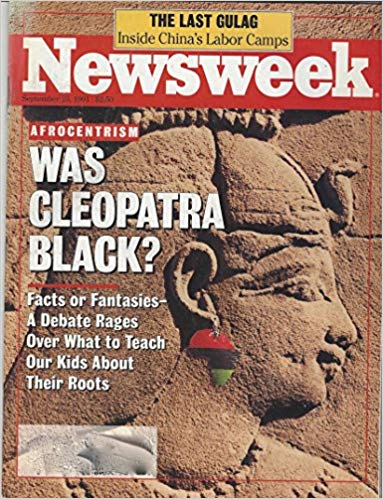

Bernal’s work set off a firestorm in the field of classics, but his primary focus on Greek cultural development was soon overshadowed by the attention given to his passing comments about Egyptian skin color. Once again, the veil of culture had seemingly been lifted, and race was exposed underneath. Arguing for the blackness of ancient Egyptians (sort of), Bernal became strongly associated with Afrocentrism in the public imagination, and the entire controversy landed on the cover of Newsweek in September 1991 under the headline: “Was Cleopatra Black?”

The long-term effects of Black Athena have been tough to gauge. Some classicists certainly internalized the imperatives of Bernal’s work in intangible and often unspoken ways, leading us on new paths for crafting our professional practice as classicists. But many eminent scholars at the time simply struck out, desperately trying to “protect” their beloved Greeks from the onslaught of, um, critical examination.

While there is little sustained discussion of Bernal’s hypothesis today, classicists continue to debate the origin and history of our own field, even as we try to shape a more inclusive future.

A Greek Myth that Won’t Die

During the 2016 election cycle, Representative Steve King (R-IA), appearing on MSNBC, responded to the characterization of a group at the Republican National Convention as “loud, unhappy, and dissatisfied white people,” expressing his deep frustration with what he called “this white people business.”

King then demanded that the panel of pundits “go back through history and figure out where these ‘contributions’ (are) that have been made by these other categories of people that you are talking about.” He further asked, “[W]here did any other ‘subgroup’ of people contribute more to civilization?”

Representative Steven King on MSNBC in July 2016.

When pushed by the MSBNC host, Chris Hayes, on whether he was talking about “white people,” King reframed his premise in terms of “Western Civilization itself,” a space “rooted in Western Europe, Eastern Europe and the United States of America” and “every place where the footprint of Christianity (has) settled the world.”

Clearly sensing that the conversation was getting out of control, Hayes intervened to close the discussion, pointedly reminding his audience that “we are not going to argue the history of Western Civilization.”

Oh, but we are, Chris Hayes, we are.

The Greeks and Romans have given us many “gifts”—and, without doubt, many parts of that heritage are darker than others, not least the philosophical justifications for chattel slavery.

A 2018 Identity Evropa demonstration in front of a recreation of the Parthenon in Nashville, TN.

But even as we continue to debate the meaning and values of “Western Civilization,” we also need to confront current attempts to situate race rather than culture as our “inheritance.” For one thing the Greeks and Romans never bestowed on us is the concept of “whiteness.”

So, now more than ever, we need to bring the same critical inquiry the Greeks and Romans used to interrogate their world to unmask the distorted meaning being made of their legacy today.

Read and Listen to Origins for more: Rome and Athens in American Sports Culture; What We Talk About When We Talk About Confederate Monuments; Confederates and Lynching in American Public Memory; White Supremacist Violence; Rome's Rivers; Augustus; and Thessaloniki, Greece.

Eric Adler, Classics, The Culture Wars and Beyond (University of Michigan, 2016).

Kwame Anthony Appiah, “There is no such thing as western civilization,” https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/nov/09/western-civilisation-appiah-reith-lecture

Martin Bernal, Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization, Vol 1: The Fabrication of Ancient Greece 1785-1985 (New Brunswick, 1987).

Debbie Challis, The Archaeology of Race: The Eugenic Ideas of Francis Galton and Flinders Petrie (Bloomsbury, 2013).

William W. Cook and James Tatum, African American Writers and the Classical Tradition (University of Chicago, 2017).

Tenney Frank, “Race Mixture in the Roman Empire,” The American Historical Review 21.4 (1916).

Stephen Howe, Afrocentrism: Mythical Pasts and Imagined Homes (Verso, 1998).

Josephine Livingstone, “University History Departments Have a Race Problem,” The New Republic (https://newrepublic.com/article/145501/university-history-departments-race-problem).

Margaret Malamud, African Americans and the Classics: Antiquity, Abolition and Activism (I. B. Tauris, 2016).

Neville Morley, Classics: Why it Matters (Polity, 2018).

Carl Richard, Greeks and Romans Bearing Gifts: How the Ancients Inspired the Founding Fathers.

Frank Snowden, Jr. Blacks in Antiquity (Harvard University Press, 1971).

Barry Strauss, “The Black Phalanx: African-Americans and the Classics After the Civil War,” Arion 12.3 (2005), 39-63.

Donna Zuckerberg (forthcoming), Not All Dead White Men: Classics and Misogyny in the Digital Age.