Americans now buy more salsa than ketchup each year and that's been true since 1992. Let salsa stand for a whole host of wonderful Mexican and Mexican-adjacent foods that Americans love to eat. This month scholar Andrew Mitchel traces how Mexican food has become as American as apple pie.

Though restaurants and their customers use such words as “traditional,” “authentic,” and “pure,” recipes and cuisines are similar to all other historical phenomena: They change over time. This is certainly the case for Mexican food in the United States, which has undergone many transformations.

It emerged from the distinct culinary traditions of the people of the Southwest whose desire for dishes like chili and tacos increasingly brought these foods into the American diet. As Mexican immigrants arrived in new locales, various forms of regional Mexican food, including barbacoa and birria, became widespread in the United States.

The popularity of these dishes and Mexican ingredients pushed Mexican cuisine into fast food with the founding of Taco Bell and the archetype of the Tex-Mex cantina. It also incorporated Mexican food into the fine dining scene through celebrity chefs.

Despite popular appeal, a modern split has emerged in Mexican cuisine. It is visible in how eateries such as Chipotle utilize Mexican ingredients but American service, while Mexican migrants claim their own space and identity through food.

Borderlands Cooking: Tortillas, Chiles, and Chile Powder

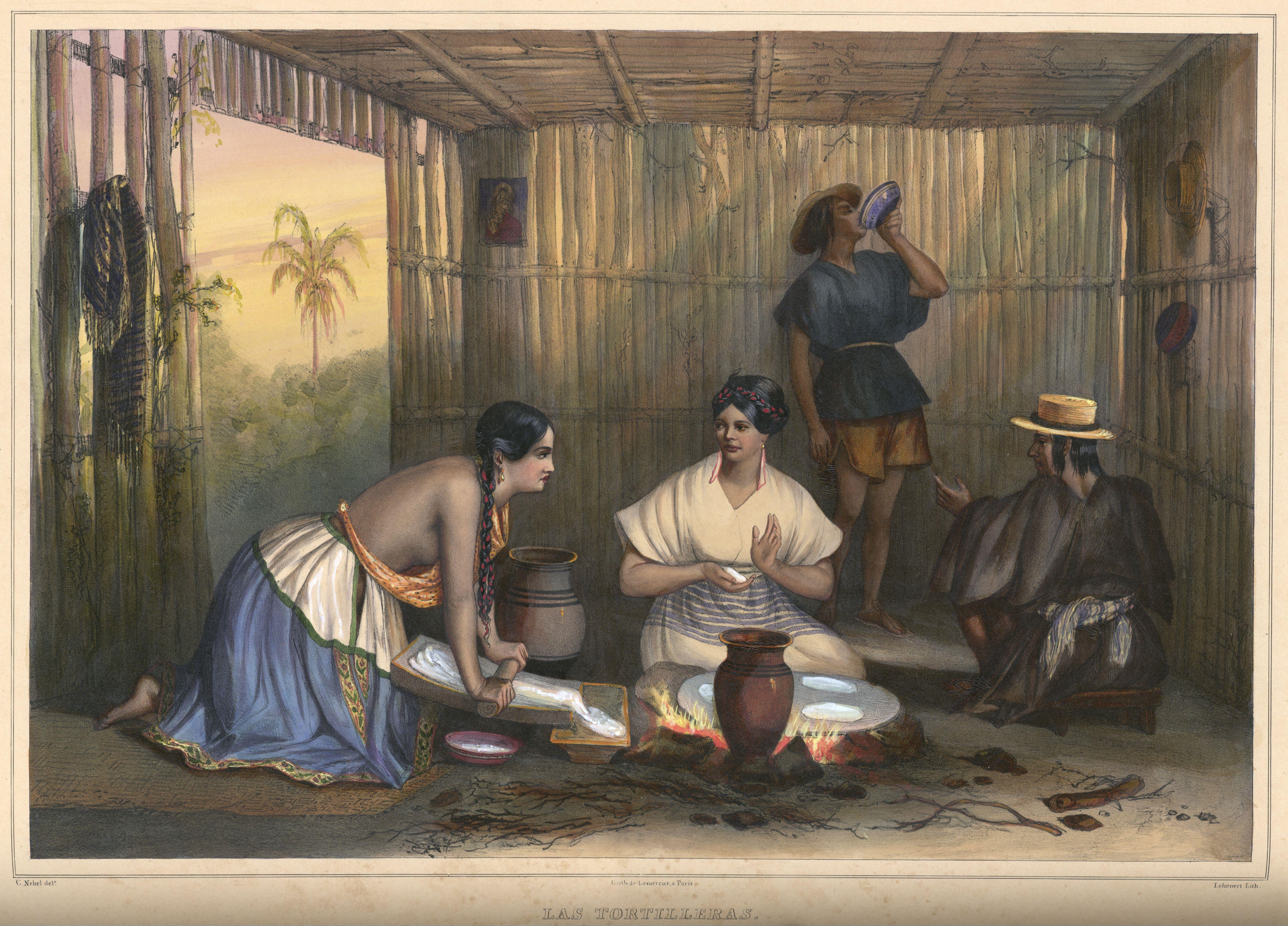

The food tradition of the American Southwest has come about through various populations’ contributions over several centuries. Many Mexican foods have indigenous origins: corns, beans, and squash are all native plants, and Mesoamerican peoples pioneered the “nixtamalization” process of soaking corn kernels in an alkaline solution to make a workable dough for tortillas and tamales.

Then came the Spanish conquest and the Columbian Exchange, which introduced various European foods, including wheat, pork, and beef to the region.

The final culinary change came with the arrival of American ingredients and sensibilities about taste and spice following the ceding of Mexican territory to the United States in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the Mexican-American War in 1848.

These historical encounters created distinct foodways in the borderlands where Mexico and the United States meet.

New Mexico is known especially for its distinct red and green Hatch chiles, and the state aroma is the smell of them roasting. These varieties were first introduced by Dr. Fabián García, the first American horticulturalist to publish in English and Spanish at the turn of the 20th century.

These food traditions are imbued with timelessness to create a fanciful heritage for tourists; however, this does not diminish the native and Spanish origins of dishes like tamales.

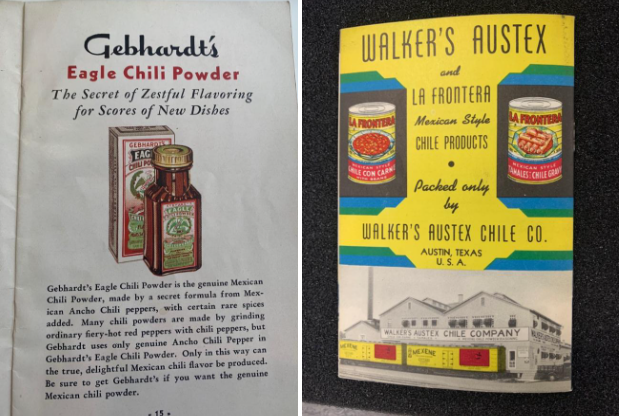

In Texas, William Gebhardt at first imported ancho chiles to grind into chili powder in his New Braunfels, Texas restaurant in 1894. He is widely credited as the inventor of this product. He soon thereafter founded Gebhardt’s and built a factory in San Antonio for nationwide distribution of his now-patented Eagle Chili Powder two years later in 1896.

Companies such as Gebhardt’s and Walker’s Austex Chile Company in Austin not only sold their products but also disseminated Mexican recipe books to the American public. They introduced these foods to new audiences and made dishes like canned tamales in meat sauce into weeknight family meals nationwide.

Today, brands such as Ortega and Old El Paso market salsa, refried beans, and other such products in massive numbers. The adage that salsa outsells ketchup has been true since 1992. The initial introduction of Mexican products by Gebhardt and other innovators over 100 years ago has had a sustained impact on the American palate.

Culinary Introductions: Chili, Tacos, and Tex-Mex

Chili, or chili con carne, first came into the American consciousness via San Antonio’s Chili Queens. Though often derided by public health officials, these women street vendors in the main public square served tasty dishes to hungry workers and tourists from the 1880s on.

The dish spread nationwide as San Antonio’s dual nature as a military town with transient servicemen and as a tourist site based on a fantasy heritage of the Alamo brought in many to enjoy and then crave chili.

Chili arrived on the national table at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago, which included a San Antonio chili tent. The meatpacking industry, which largely at this time operated out of Chicago’s stockyards, sold canned chili to make use of their scraps.

Tacos also spread rapidly, spurred largely by the now-global chain Taco Bell.

This restaurant was first opened in 1962 by restauranteur Glen Bell, who originally owned a burger stand in Downey, California. These types of luncheonettes with small menus, assembly line food production, and low prices were omnipresent along the roadways of Southern California. Tacos were the ideal handheld food for these eateries, and many operators sought to perfect the production of V-shaped, hard-shell taco as a delivery system for cheese, lettuce, and ground beef.

In Taco Bell’s case, Bell learned how to make this style of shell from Mexican family who ran the nearby Mitla Café. He opened an eatery in San Bernardino in 1962 with five items on the menu, and he followed that with a franchise called Taco Tia in 1965 in Torrance, California. The rest is history. As of 2022, Yum! Brands, a Chinese company, operates 8,218 Taco Bell restaurants in 32 different countries.

The popularization of this simplified Mexican cuisine was based on a 1960s-style California fast-food concept. It comprised dishes, like easy-to-make tacos, that were fashioned by the tastes, desires, and whims of the white consumer. There remains little worry about spice level, unfamiliar ingredients, or cleanliness at Taco Bell. This approachable version of Mexican food maintains its indelible impact on the American food landscape.

Tex-Mex, short for Texan-Mexican, cuisine emphasizes Mexican preparations using uniquely American ingredients—yellow cheese, beef (supplied by local ranching)—and spices like cumin. Spanish immigrants to Texas from the Canary Islands introduced this use of Middle Eastern spices.

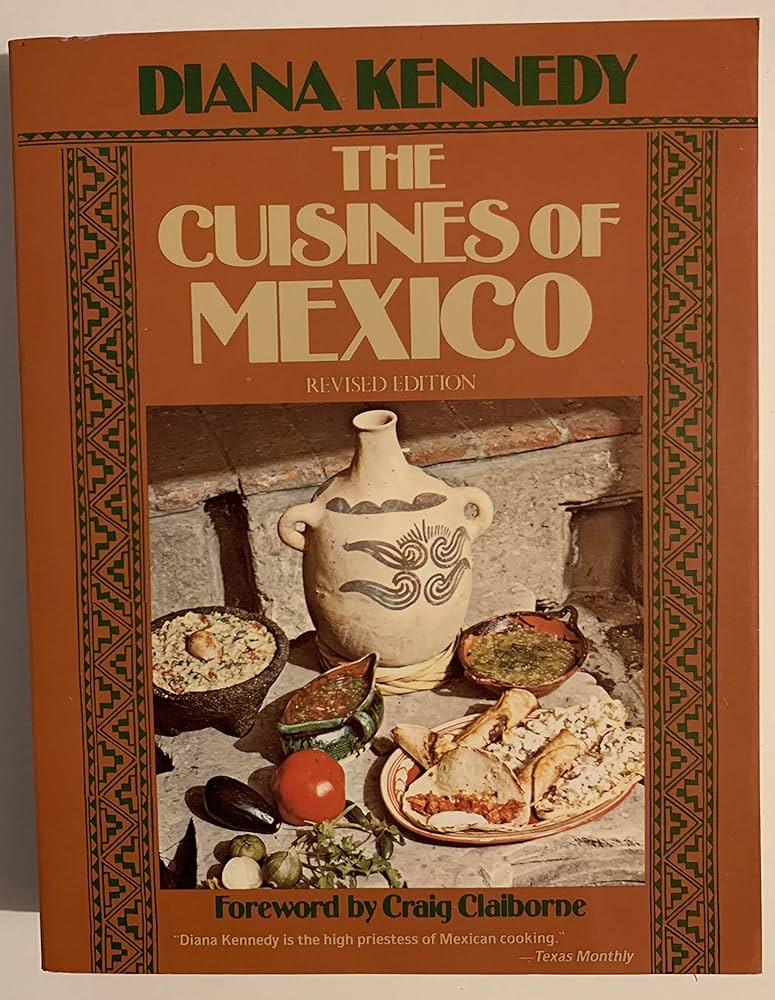

Mexican food beyond Taco Bell was unveiled to the broader American public not by groups like the Texan women who cooked these foods for generations, but in the 1970s by cookbook writers such as Diana Kennedy with the capital to collect and publish these recipes.

Kennedy’s first cookbook, The Cuisines of Mexico, put Mexican food on the map in 1972 with its collection of recipes she personally gathered from every state in Mexico. Though she viewed Tex-Mex as simplistic, it was this form of Mexican food that rose to popular acclaim thanks to its presence across the Southwest and a wide desire for these palatable preparations and flavors.

Tex-Mex echoes the food of the U.S.-Mexico borderlands but is the abridged version of the cuisine. El Cholo, a restaurant that calls itself a Spanish cafe and is celebrating 100 years of operation in Los Angeles, retains its original mild enchilada sauce recipe to match the broader tastes of the era in which it opened.

European-descended Americans were generally unfamiliar with hotter spices in their daily consumption until the introduction of cuisines like Mexican, Chinese, and Thai. Western European cuisines popular in the United States such as German and Italian food do not use chili pepper as a common ingredient and thus lack the piquancy of traditional Mexican food.

These new tastes were illuminating: the now-ubiquitous Tex-Mex spot is a fast-casual, sit-down restaurant found in most American cities and towns. It serves such dishes as tacos, burritos, or cheese-covered enchiladas with a side of rice and beans in a festive environment.

Tex-Mex style eateries have produced dishes like nachos, invented in Mexico by Ignacio “Nacho” Anaya, and the margarita, made famous by the mercurial Larry Cano who operated a Mexican restaurant in Encino, California in the 1950s.

Restaurants are shaped by customer expectations, and Tex-Mex is the style of this food that became exceedingly popular nationwide.

This hybrid popularization of Mexican is echoed in a few modern trends. Avocado toast has been raised up as an ideal food seen not just as a healthful breakfast, but a moniker of millennial culture. Many eateries claim to have made it popular, including locales in Australia, but Sqirl in Los Angeles lays claim to its (knowingly) pretentious preparations, one of which has twenty-two ingredients.

Mexico remains the primary grower of this fruit, evidenced by the past few years of “Avocados From Mexico” Super Bowl advertisements. However, avocados are grown in states like Michoacán where cartel activity is high. Thus many question whether avocados are a global conflict commodity comparable to Africa’s so-called blood diamonds.

Regional Mexican Fare: Barbacoa and Birria

New forms of regional Mexican food have recently become popular as Mexican migrants move to states and locations outside of such traditional destinations as Southern California and Chicago. This changeover is shaped by cosmopolitan consumers who desire new ingredients and tastes and by Mexican businessowners who have obtained more support and capital to open loncheras (taco trucks) and, in turn, restaurants.

South Philly Barbacoa, opened in 2018, is a perfect example of this: chef Cristina Martínez, an undocumented Mexican immigrant, has parlayed her successful food truck into restaurants across Philadelphia. Her cooking style is primarily barbacoa, a traditional Mexican meat preparation where the beef, lamb or goat is slow cooked in a caldo (or massive stew pot) for hours.

In New York City, a more recent destination for Mexican migrants, the latest Mexican food trend is birria. This dish, heavily popularized through social media, consists of birria de res (either beef or goat) stewed meat in tacos. When served in the Tijuana style found at taco truck Birria Landia, tortillas are bright orange, as they have been dipped and fried in their cooking liquid, which is also served on the side as consommé for dipping.

High consumer demand has prompted many restaurants to switch to selling exclusively birria. Many of these are run by immigrants who are not from Jalisco or another state where birria is popular.

This raises the question of whether Mexican heritage chefs can cook dishes they are comfortable with in their restaurants, as opposed to those demanded by their clientele. New destinations of settlement introduce new markets for Mexican food yet remain shaped by consumers’ presumptions about what Mexicans should, if not must, cook.

Mexican Fine Dining: Can Tacos be Haute?

Mexican food, of whatever sort, has usually been cheap. Thanks to hierarchies of cultural value created by histories of exclusion, breaking the idea that Mexican food is only cheap and family-friendly has been difficult for most Mexican chefs.

One who has broken this mold is Oakland chef Dominica Rice-Cisneros. Her original restaurant Cosecha emphasized nuanced preparations of Mexican classics. Her new project Bombera, opened in 2021, makes use of local, fresh ingredients; puts history back into food; provides work for women and minority chefs; and pushes the boundaries of Chicano Heritage cooking. This newfound approach pushes Mexican into haute forms through thoughtful, intentional preparation.

Chicago-based chef Rick Bayless runs a restaurant empire including both the festive Frontera, opened in 1987, and buttoned-up Topolobampo, launched next door in 1989.

There are questions as to whether Bayless should be able to use his personal travel to Mexico to turn a profit. He learned this cooking from various Mexican experts who told him which ingredients to use; he then adapted these dishes and techniques for the American restaurant in his eateries and for the home kitchen in his cookbooks.

In my view, the more appropriate question is, when is Mexican food allowed to be pricey? Bayless’ eateries, from the sleek to the mass-produced (Frontera has a location selling tortas at the O’Hare Airport) can charge a high price thanks to name recognition and the prestige of eating food served from a restaurant with a Michelin star.

Chipotle and Migrant Place-Making: A Split

A modern split has taken shape within Mexican food in the United States. Chipotle-style fast-casual, make-your-own eateries reflect the continued popularity of burritos and tacos. The burrito as a handheld combination of ingredients is a Northern Mexican tradition popularized and commodified in the United States in spaces like the Mission District of San Francisco, then made ubiquitous by the Chipotle and Qdoba chains.

Chipotle’s appropriation has been brought into question thanks to the choices to utilize Mayan hieroglyphs and characters in many of their restaurants. One might assume tortillas of this size, and eateries that stuff them with various fillings, have long existed. However, they have only been around since the 1990s. This proliferation of the fast-casual eatery shows a continuing desire for new flavors and tastes, but in many cases without the very people who traditionally cook a version of this cuisine.

Even as these increasingly mainstream varieties of Mexican food proliferate, grassroots efforts like the Mercado Central in Minneapolis preserve and amplify the food of Mexican immigrants.

Opened in 1999, the market has helped to revitalize a commercial area in Midtown of the city most greatly impacted by protests following the murder of George Floyd in the summer of 2020. The space contains some 30 businesses of various Latin American origins and has been a community bastion, with the Mercado management providing business owners with access to loans and assistance with their business plans.

Similar to South Philly Barbacoa and Birria Landia, it is a draw for locals but also invites visitors to experience Mexican food, reflecting the careful balance among tourism, local businesses, and cultural preservation that Latin neighborhoods are forced to negotiate across the United States.

Mexican cuisine in the United States includes a plethora of distinct styles that echo historical processes of invention, popularization, and proliferation.

Southwestern traditional dishes such as chili and tacos were popularized nationwide by companies like Gebhardt’s and led to Mexican food becoming fast food at eateries like Taco Bell. Regional Mexican food has coalesced nationwide as Mexican people moved to new communities and brought their distinct food traditions, such as birria, with them. Mexican food as fine dining continues to be bridged only by those with the capital and privilege to set high price points.

Hybrid foodways continue to support Mexican foods and markets, both in top-down ways like the popularity of the avocado and Chipotle as well as in the bottom-up grassroots formation of Minneapolis’ Mercado Central.

Such historical trends as Mexican migration in the United States and commodification of their ethnic food traditions are reflected in every taco we enjoy.

Arellano, Gustavo. Taco USA: How Mexican Food Conquered America. New York: Scribner, 2012.

Foulis, Elena and Glenn Martinez. "Constructing La Villa Hispana: Cultural

Citizenship, Economic Development, and Linguistic Landscaping in Ohio." In Spanish Across Domains in the United States: Education, Public Space, and Social Media. Ed. Edwin Lamboy and Francisco Salgado-Robles. Boston: Brill, 2020.

Lemon, Robert. The Taco Truck: How Mexican Street Food is Transforming the American City. Urbana-Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2019.

Light, Ivan, and Elsa von Scheven. “Mexican Migration Networks in the United States, 1980-2000.” The International Migration Review 42, no. 3 (2008): 704-728. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27645272.

Martínez-Cruz, Paloma. Food Fight!: Millennial Mestizaje Meets the Culinary Marketplace Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2019.

Pilcher, Jeffrey M. Planet Taco: A Global History of Mexican Food. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.