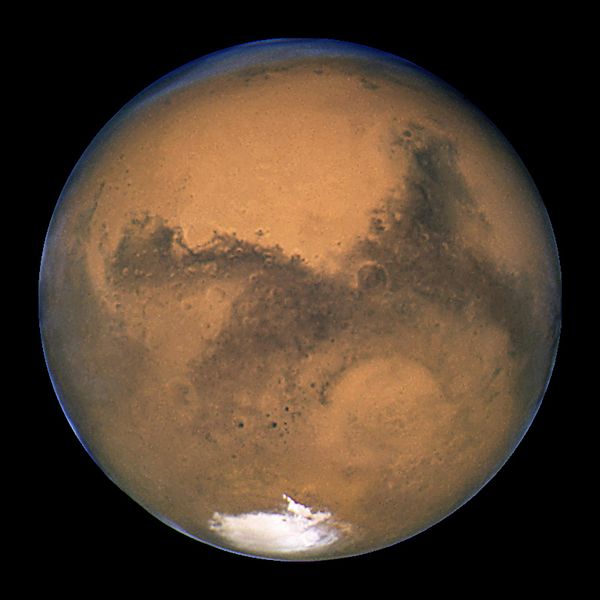

Photograph of Mars taken by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2003.

Mars, the red planet so close to Earth, has become a tantalizing target for humans to visit. Noted space entrepreneur Elon Musk recently released plans to colonize Mars in the coming decades, using a network of space hardware to get there. But as the movie The Martian reminded us last year, it is a harsh and unforgiving environment. The gravity is lighter, the atmosphere is thinner, and we still don't understand very much about its geologic history. Water flowed in the distant past, but the liquid disappeared eons ago when the atmosphere thinned.

When we think about Martian explorers today, we mostly hear about two rovers that trawl small zones of the planet: the Opportunity rover that exceeded a marathon's distance in 2015, and the Curiosity rover that is trying to track down habitability in the planet's ancient past. Neither of these rovers would have been possible, however, without a mission that happened 45 years ago this month.

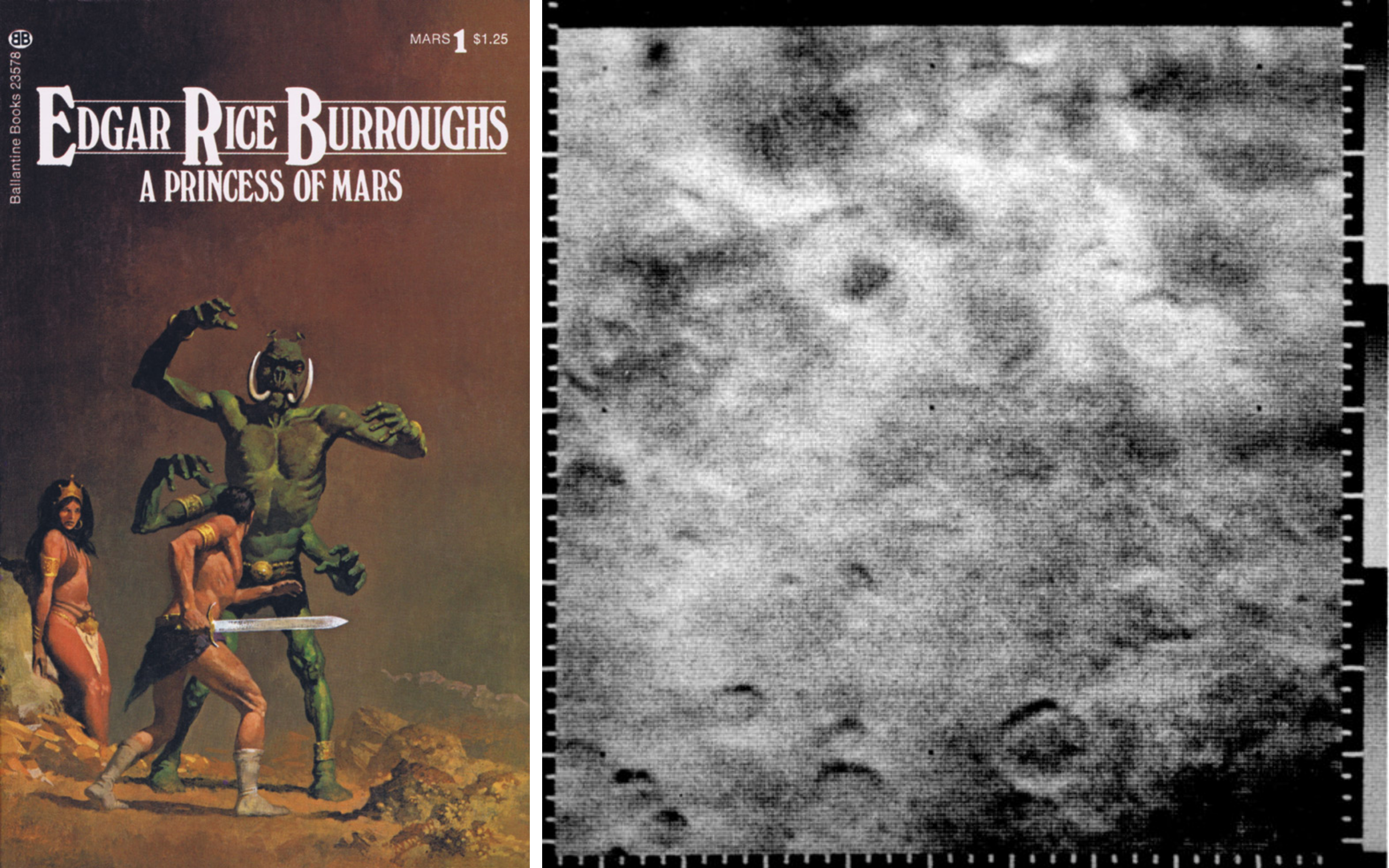

We knew practically nothing about Mars at that time. Flybys from Mariners 4, 6 and 7 showed a disappointing planet. It turned out to be nothing like the interesting desert world we were promised in classic science-fiction novels such as Edgar Rice Burroughs’ A Princess of Mars. The pictures we had from those spacecraft showed a barren surface mostly made of craters. Just like the moon.

Imagined Martians from Borroughs' A Princess of Mars (left) and a Mariner 4 image of Mars' surface craters (right).

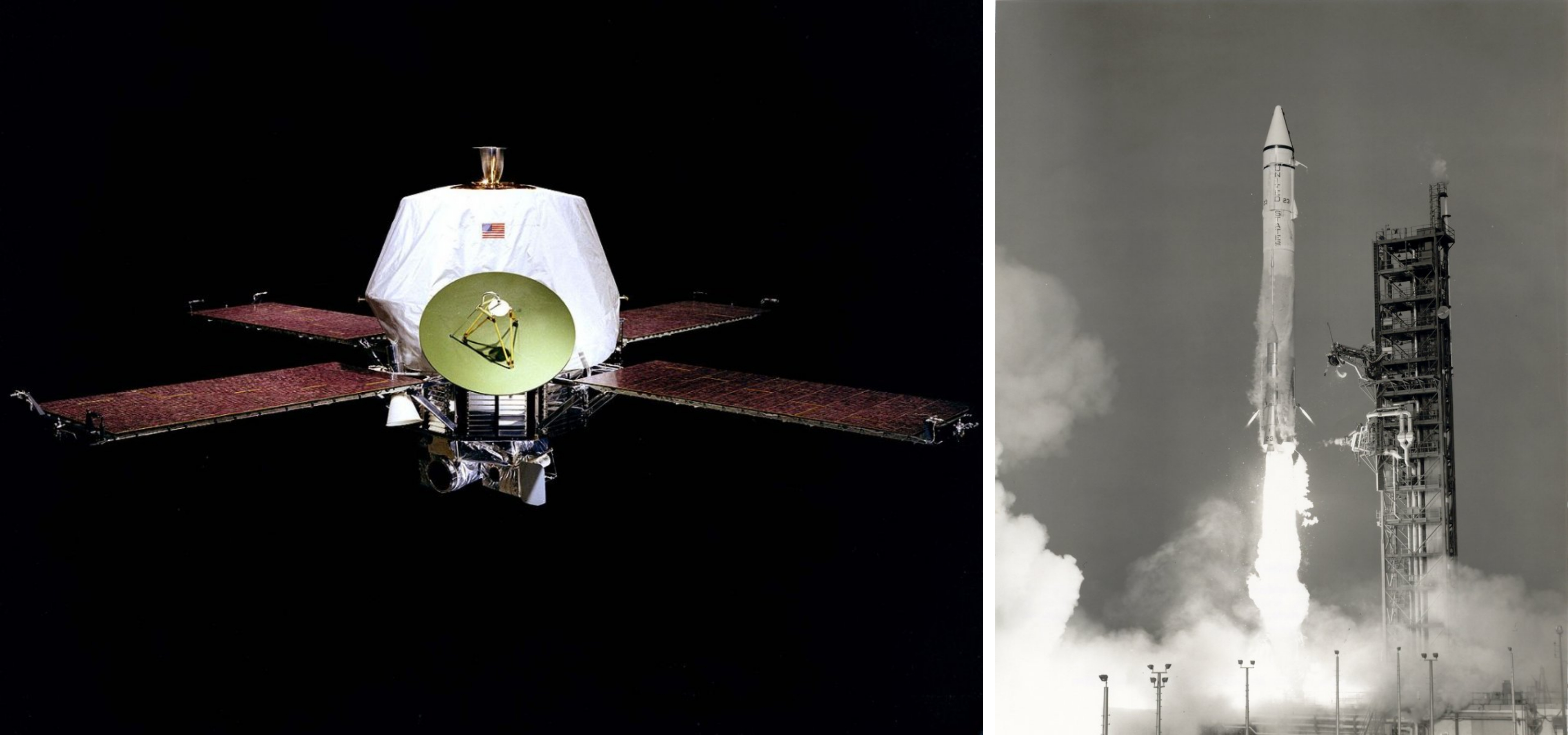

NASA, however, wanted a complete picture of the planet. It set aloft Mariners 8 and 9 to map as much of Mars as possible. Mariner 8 failed shortly after launch due to a rocket problem, but Mariner 9 made it all the way there. When it arrived Nov. 13, 1971, a surprise awaited. Rather than the now-familiar craters below, it spotted a planet-engulfing dust storm.

The Mariner 9 spacecraft (left) and the Mariner 9 launch on May 30, 1971 (right).

This obscured vision would have spelled disaster for scientists if the spacecraft had been yet another flyby. But Mariner 9 was an orbital mission. NASA scientists waited a few months until the dust subsided to see what was below. Strange features were popping up above the dust in one area. When the dust began to recede, to scientists' delight they saw ancient volcanoes. This included Olympus Mons, which is three times higher than Earth's Mount Everest.

More surprises awaited.

There was a huge canyon system slicing much of the planet, later called Valles Marineris. Layered ice deposits showed up at the poles. Perhaps most intriguingly, there were signs of water activity in the past – sediments piled up suspiciously, and flowing features that looked an awful lot like ancient rivers. With the new pictures in, many scientists couldn't wait to get a lander on the surface to look around.

Mariner 9 saw strange features on the Martian surface, such as the Nirgal Vallis channels. (Source: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

The public loves seeing pictures, but we also can't forget other scientific data Mariner 9 gathered at Mars. The spacecraft showed that the volcanoes it spotted are likely dormant, because there were no signs of eruptions in the atmosphere. It did precise altitude measurements of the surface so that scientists could compare features. It also measured components of the atmosphere such as water vapor, ozone, and pressure, providing an idea of what the Martian environment is like.

All told, Mariner 9 beamed back a wealth of information and pictures before running out of attitude control fuel in 1972, which effectively ended the mission.

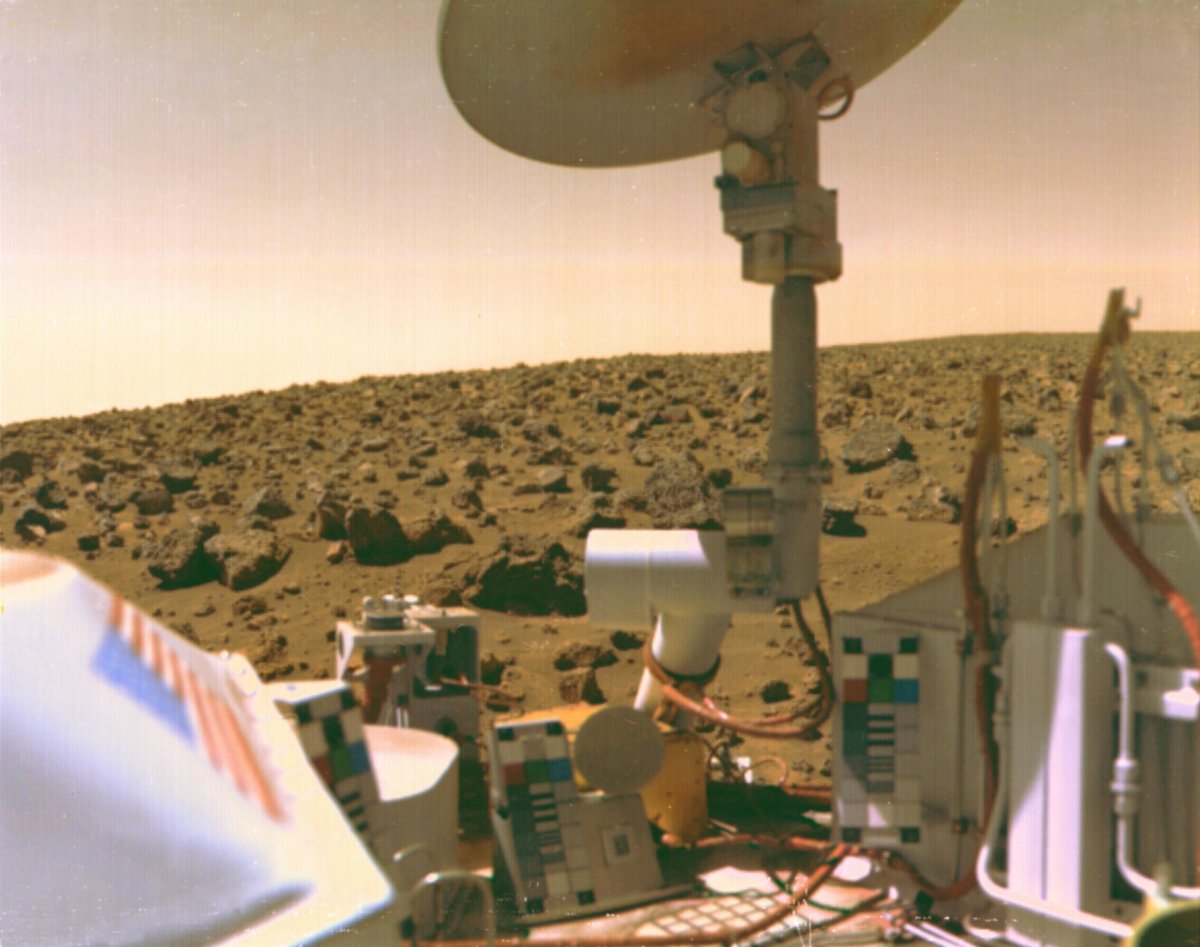

View of the rocky horizon taken from Viking 2 after landing on Mars in September, 1976

The spacecraft’s Martian exploration was brief, but just about everything that has flown out there since is directly descended from the science Mariner 9 performed. For example, Martian landings, like the two Viking missions in 1976, were possible because of the information about the Martian atmosphere collected by Mariner 9. Data from one of the Viking missions continued arriving for six years.

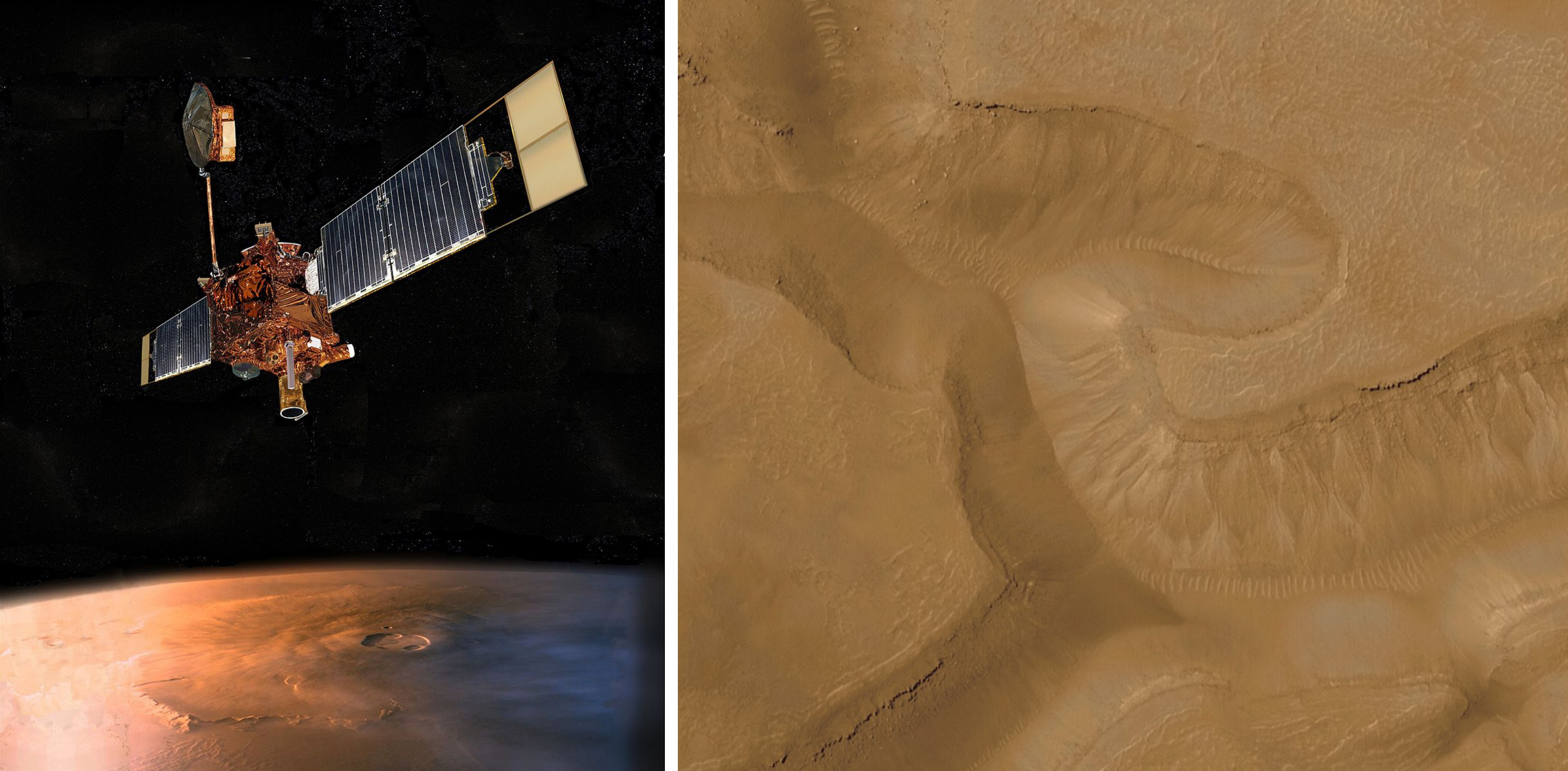

Those flowing features Mariner 9 spotted also hinted at life and water. In the 1990s, NASA’s Mars Global Surveyor mapped Mars in high resolution for the first time, and the agency sent its first rover (Sojourner) to the surface. These missions are long concluded, but form the backbone of the fleet of Mars spacecraft today.

Artistic rendering of the Mars Global Surveyor (left) and a close-up of gullies in Gorgonum (right).

By the early 2000s, we spotted past water evidence from orbit (in the form of the mineral hematite, which forms in water) as well as from the ground (in rocks analyzed by the Spirit and Opportunity rovers). This water discovery has led to more missions and today we have a dizzying amount of information coming from the Red Planet. We have orbiters from NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA), and India. We have two NASA rovers on the surface, NASA plans another rover launch in 2020, and a separate ESA-Russia rover should leave Earth then, too.

What do we know of Mars?

Certainly more now than we did when Mariner 9 got there, although the mission ended up being frustrating in a sense. We thought we had some of the answers about Mars, and then Mariner 9 showed us just how little we knew. It was a good demonstration of how science and technology literally open new worlds for discovery.

The Mars explorer Curiosity's view back at its own tracks after crossing a sand dune in 2014.