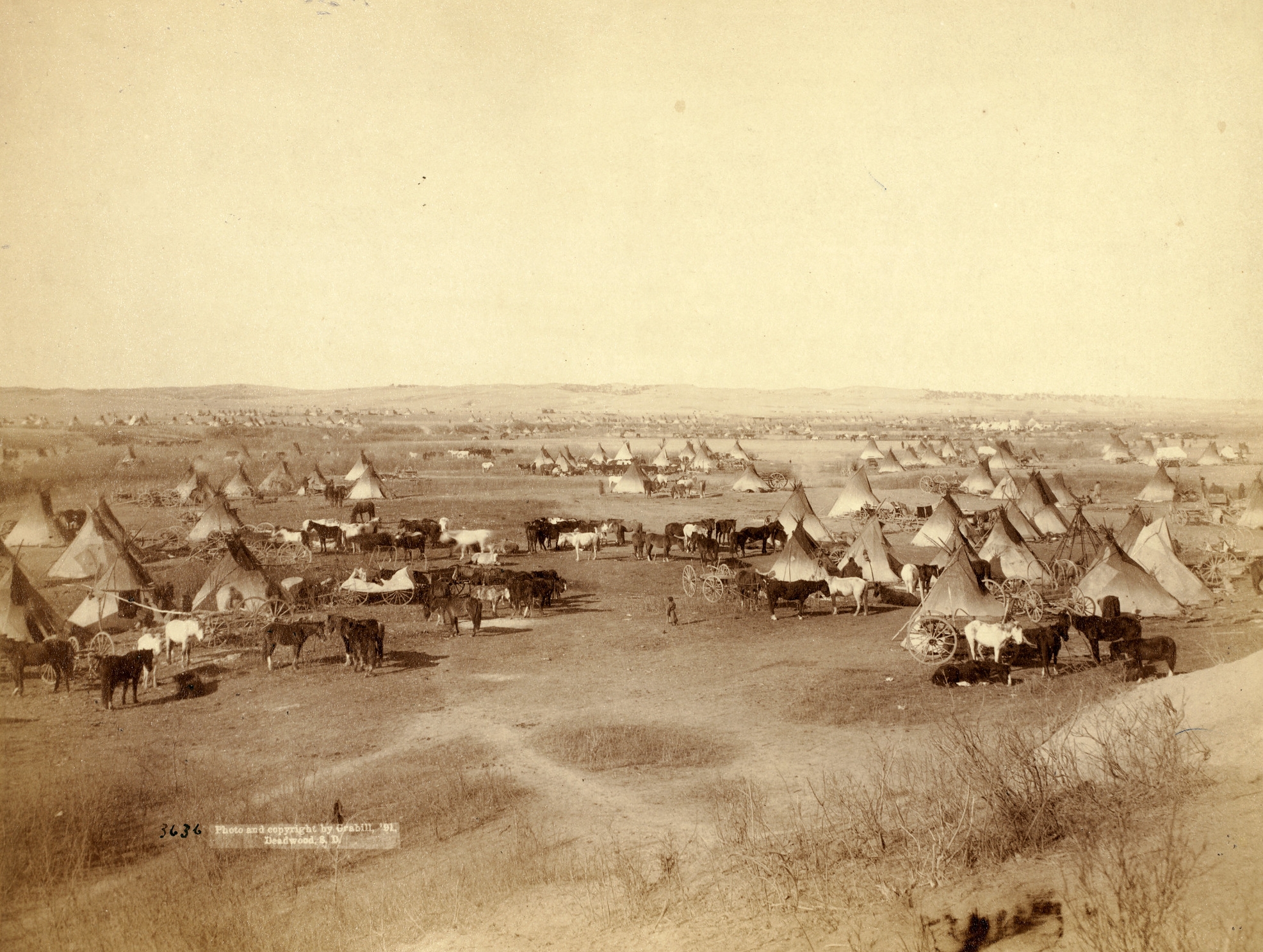

Until the late nineteenth century, tribal nations across the United States owned their reservation lands as a community: families could settle, plant their crops, and own any improvements they built, but the land itself belonged to the entire nation for future generations’ use.

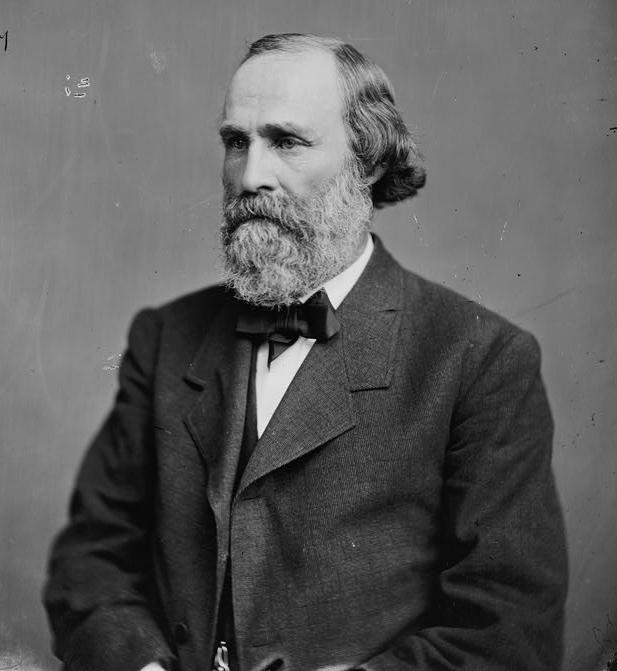

The 1887 passage of the General Allotment Act, colloquially known as the Dawes Act, upended this system of communal land ownership and, in doing so, struck a historic blow at Native Americans’ political rights, economic sufficiency, and cultural heritage.

The act ordered the division of reservations into small parcels—160 acres went to the head of a family, 80 acres to unmarried adults, 60 acres to minor orphans, and 40 acres to other children—and further mandated that all Native peoples were required to become American citizens and subject to the state in which they resided.

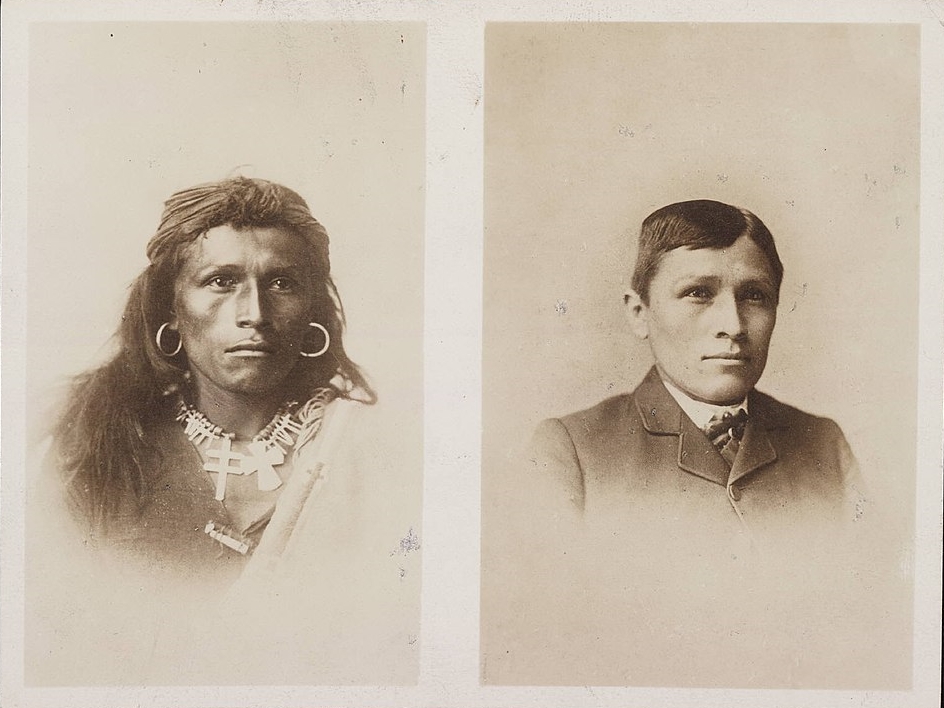

Indeed, the land allotment scheme was in one sense a project of social engineering, grounded in the assumption that dismembering communally-owned reservations and redistributing them as private property would make Native peoples into better, more “civilized” members of the United States.

Senator Henry Dawes of Massachusetts, the act’s architect, certainly thought so. Addressing a meeting of white progressive reformers at the Mohonk Lake House resort in 1885, he said of Native peoples: “They have gone far as they can go because they own their land in common. There is no enterprise to make your home any better than that of your neighbors. There is no selfishness, which is the bottom of civilization.”

Without the ethos of greed and competition against their fellow citizens, Native peoples would never, in the view of Dawes and his audience, reach the threshold of civilization.

This view developed despite strong evidence to the contrary.

Dawes had spent that summer in the Indian Territory meeting with leaders of the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole, known as the Five Civilized Tribes. The report of the Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation had shown that “there was not a family in that whole Nation that had not a home of its own” and that the Nation had successfully “built its schools and hospitals.” Dawes’s land allotment plan—his remedy to Native peoples’ allegedly uncivilized lifestyle—was clearly a solution without a problem.

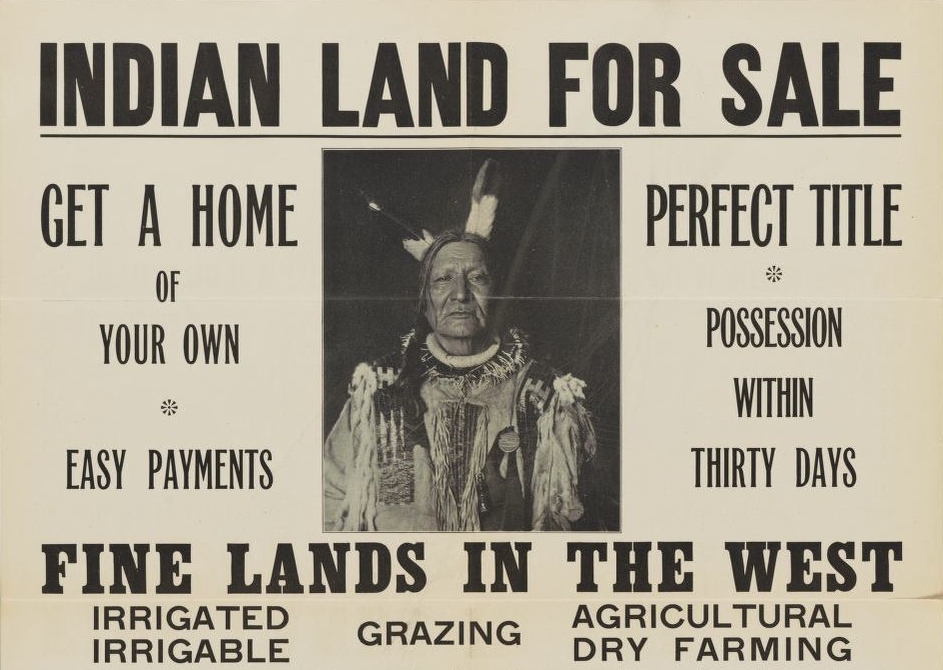

Beyond the paternalistic rhetoric of civilizing Indians, however, the unspoken goal of allotment was the transfer of hundreds of millions of acres of land from tribal communities to the United States.

At the time of the Dawes Act’s passage, the United States was only composed of thirty-eight states, and the admission of many of the Western territories required the extinguishment of Native titles to their lands. Under the act’s provisions, once reservations had been divided among tribal citizens, any remaining unallotted lands, deemed “excess” lands, were ordered to be sold to white settlers.

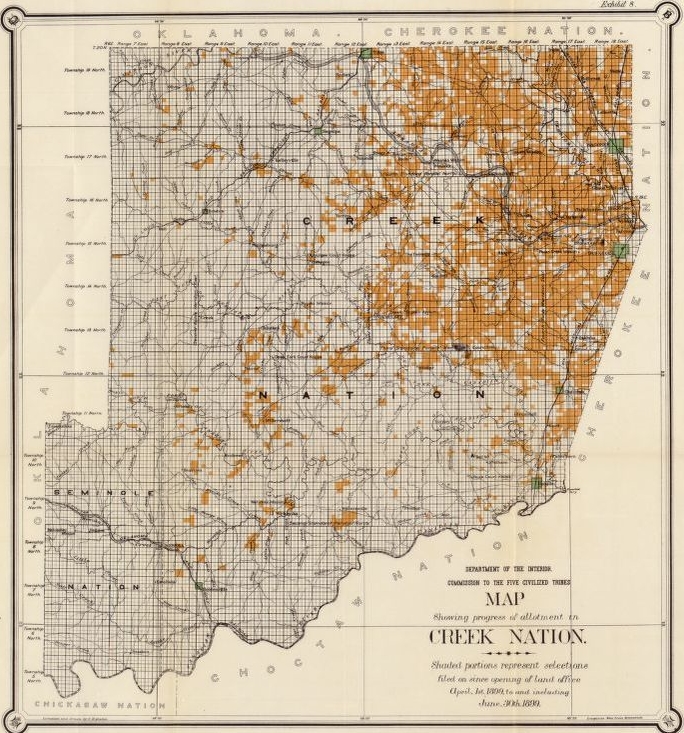

Though the final draft of the Dawes Act exempted several nations from its provisions, over the next decade, Congress approved several subsequent acts that extended allotment to any previously exempted tribes.

The most well-known of these acts was the Curtis Act of 1898, named after its author, future Vice-President Charles Curtis, a citizen of the Kaw Nation and then representative from Kansas, which allotted the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole Nations in Indian Territory.

Attempts by Senator Dawes and white progressives to incorporate Indigenous peoples into American society by diminishing tribal sovereignty also necessitated a loss of political rights.

While U.S. citizenship is often framed positively by extending civil rights to minority populations, for Native peoples, it often abrogated the protections and rights afforded to them by their tribal nations.

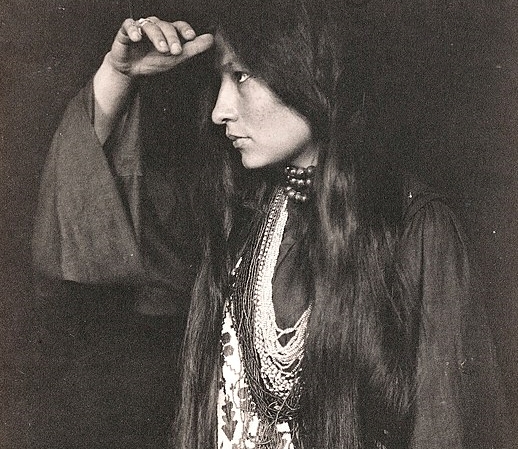

Even as the Dawes Act placed Native peoples under the legal jurisdiction of states, many states passed laws explicitly banning Native Americans from voting. The extension of American citizenship particularly harmed Native women. Unlike American women who could not vote, in many Indigenous societies, women had had their own political leadership or the right to vote in tribal elections.

Federal attempts to incorporate Native Americans by dismantling tribal governments left them at the mercy of state legislatures seeking to disenfranchise them. Not until 1962 did all fifty states guarantee Native peoples the right to vote.

Though many Americans may have believed they were acting in the best interest of Native peoples, allotment was merely the continuation of Federal policies designed to dismantle tribal nations and exterminate Indigenous cultures.

The allotment of tribal reservations worked in tandem with other Federal efforts of the late nineteenth century, including Indian Boarding Schools that sought to “Kill the Indian, save the man,” and which worked to eliminate Indigenous languages, cultures, communities, and political sovereignty.

In many ways, these efforts were successful. Boarding schools and other assimilationist programs severed the connection many Native peoples had with their language and culture.

Furthermore, allotment only further dispossessed Native peoples, commodifying a relationship with their lands that had been one of respect and reciprocity. Privatizing land ownership through allotment forced many to choose between maintaining a traditional relationship with their lands or being able to feed their families by selling their allotments to white settlers.

In most cases, allotment did not transform Native peoples into the yeoman farmers that Dawes had hoped. In that sense, his plan was a failure. Allotment did not teach Native people to embrace the civilized ethos of selfishness. Instead, allotment only resulted in the further loss of land, the breakdown of tribal communities, and, in many cases, their descent into poverty as they were thrust into an unfamiliar economic system.

It was not until 1934 that the Federal Government finally acknowledged the failures of allotment to improve the lives of Native peoples. By then, the damage had been done. In the forty-seven years since the passage of the Dawes Act, the remaining ten territories in the continental United States had been admitted as states into the Union. Tribal governments had been diminished. Boarding schools had stripped Native youth of their heritage language and culture.

Fortunately, this is not the end of the story. Over the last ninety years, tribal governments have been strengthened; reservations have been restored; and languages and cultures are being revitalized.

In the 2020 United States Supreme Court case McGirt v Oklahoma, the Court restored the Muscogee Creek Reservation, which Oklahoma had argued was dissolved in the creation of the state. Since that ruling, the judiciary has recognized the continued existence of reservations belonging to the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, and Quapaw Nations, with others sure to follow.

Today, as we remember the devastation that allotment and the Dawes Act caused Indian Country, we must also look to the present and future with hope for the continued revitalization of tribal nations.