For many people around the world the pandemic underscored just how important pet dogs have become to their human owners. This month historian Neil Humphrey shows us that dogs only became our best friends during the 19th century in England and that they occupied this position because of profound changes to society during the Victorian age.

Today, most dog owners believe two things about their dogs. The first is that they are valued family members. Dogs are loved just like their human counterparts and included in events, holidays, and celebrations.

The second is that their dogs should not work. They are for petting, cuddling, and playing. They share in leisurely activities ranging from taking neighborhood strolls to visiting pet stores. Their owner is responsible for meeting their dog’s material and emotional needs.

These family dogs have lives of leisure that seem normal—and perhaps timeless—to most owners.

However, this human-dog relationship is a recent role reversal. In the past, most dogs were working animals; they earned their keep by working for humans.

The moment when this all started to change arrived in the 19th-century United Kingdom.

The typical British dog appeared quite different at the end of the 19th century than it had at the beginning.

Around 1800, most were working animals, and those that did not work were often labeled luxuriant leeches. However, by 1900, the common dog was a faithful companion and beloved family member. While not everyone then—nor now—accepted dogs, their place in modern life was secured.

The Victorian era gave rise to the multispecies family: the more-than-human social unit that many families experience today. Pets—from caged birds and cuddly cats to wild hedgehogs and rambunctious dogs—lived in British homes by the mid-19th century. Dogs were at this phenomenon’s forefront and replaced birds, the trendiest 18th-century English pet.

Dogs transitioned into their new role as family pets due to evolving methods of work and popular culture. In turn, Victorians esteemed their dogs as jolly chums, faithful companions, and constant dependents. Some even remarked that they loved their dogs more than their human family or friends.

The Blue-Collar Canine

Why did Victorians invite dogs into their homes?

Many believed that dogs embodied an honest and faithful identity in an era characterized by moral corruption. Britons sought canine companionship when they failed to maintain connections, enduring bonds, and reciprocal belonging with fellow humans.

Up to the late 18th century, Britons lived in what they called a “dog-does-not-eat-dog” world, to use the once-common phrase. After that point, at a time when competition replaced communalism as a foundation for society, the phrase shifted to describe a “dog-eat-dog” world.

The 19th century saw wrenching social change in Britain. Although the Enclosure Movement had altered agricultural landscapes and communal life since the 13th century, the upheaval of this process of privatization of previously communal lands increased markedly between 1760-1820.

During this period, commoners who had traditionally lived in village communities were forced to relocate to industrial towns and find work as factory hands.

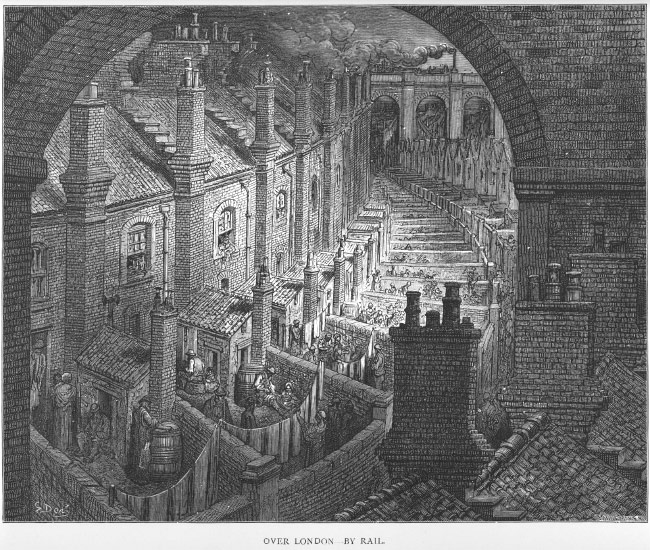

Coal-fired and steam-powered industrialization gripped the United Kingdom between 1760-1850 and transformed the working lives of many—if not all—Britons. Bewildering urbanization was already felt, particularly around London, early in the century. By 1851 England was the first urban nation.

Those living through these changes were amazed at factories that churned out all sorts of novelties. However, they were also concerned about moral degradation resulting from burdensome work, unhealthy lifeways, and urban anonymity.

Taking stock of this mechanical age, essayist Thomas Carlyle remarked that “in whatever respects the pure moral nature, in true dignity of soul and character, we are perhaps inferior to most civilized ages.”

Dogs, however, had a uniquely incorruptible character unphased by these changes. Veterinary surgeon William Youatt contended that common canine morality was not only “strongly developed and beautifully displayed,” but that it also put “the biped to shame.”

This desire for genuine fellowship did not mean that Britons immediately sought pet dogs, however. Landed gentry and wealthy merchants were often the only Britons who had owned nonworking dogs, and these were typically hunting hounds or leisurely lapdogs.

Lapdogs were closer to modern pets, although different since they were bound to one owner, uniformly tiny (toy spaniels and pugs were common), and believed by many to symbolize wastefulness.

By contrast, common dogs worked.

Dogs staffed a diverse set of roles, some that remain familiar today. Collies herded sheep in the Scottish Highlands, mastiffs guarded English cottages, and Newfoundlands hauled fishing equipment in the Canadian maritime territories.

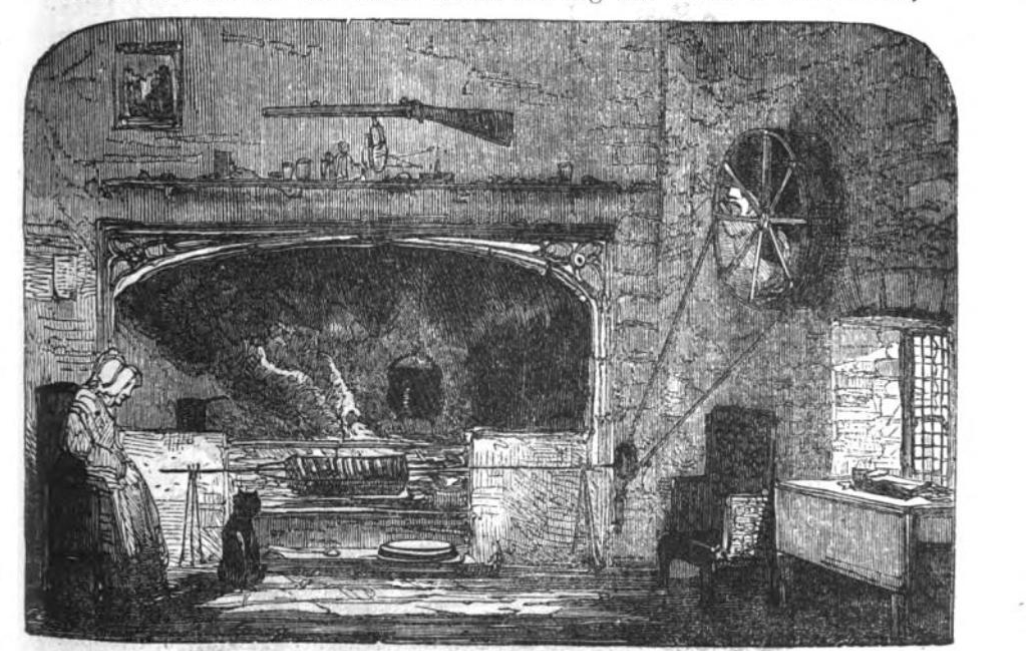

Some were odder, like turnspits, a now-extinct breed that roasted beef by trotting upon a wheel that spun a roasting spit. While these dogs could be companions once work ended, their primary identity was as workers.

From Herders to Huggers

The late-18th-century sentimental shift that spurred the animal welfare movement marked the beginning of the end for most working dogs. The belief that humans should treat animals kindly and eliminate their suffering spread quickly throughout British society.

This belief led—alongside the growth of an urban middle class that did not often interact with animals—to the formation of welfare advocacy groups like the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (formed in 1824).

By the 1830s, humane reformers claimed that kindness toward animals was an English trait. Those treating animals poorly were labeled as depraved and uncivilized.

The movement’s influence grew to reach lawmakers by mid-century. Laws followed that enshrined humaneness, like the banning of cart-pulling dogs first in London in 1840 and nationwide by 1854.

Industrial output played a connected role since dog-power failed to keep pace with increasingly efficient steam engines. Backbreaking work became unfit for these intelligent creatures due to both cultural and material transformations.

Industrialization and urbanization altered life for Britons and their dogs.

Although many dogs were barred from doing their traditional jobs, one important cultural obstacle blocked their social reinvention. The unsavory reputation for keeping nonworking dogs hung on until the early 1800s.

Lovers of the Dogs, Unite

Still, a handful of outspoken groups advocated that dogs’ ideal modern role should be serving as faithful companions.

The first was the iconoclastic group of European artists known as the Romantics. English Romantics questioned industrialization’s degrading nature and believed that fidelity was at odds with modern human behavior.

These beliefs ensured that dogs often starred in their art. Poets William Cowper, Williams Wordsworth, and Lord Byron all admired canine fidelity.

Byron’s 1808 epitaph to his devoted Newfoundland dog, Boatswain, labeled him as “the firmest friend” and compared Boatswain’s honest and faithful character against that of Byron’s deceitful and hypocritical acquaintances.

Religious authorities reckoned with how industrialization had transformed English lifeways and developed theological rationales that explained canine fidelity. These thinkers understood God’s will expressed through nature in the form of dogs’ historic utility and contended that companionship was their modern role.

For example, author Joseph Taylor hoped his books filled with tales of faithful dogs would help end their common abuse, which he argued was unwarranted in a Christian nation. He believed that dogs, “which Divine Providence has been pleased to make subservient to us… [are vital] for our assistance, amusement, and… preservation.”

Popular authors who appreciated dogs throughout the century, ranging from naturalist Hugh Richardson to anti-vivisectionist Frances Power Cobbe, historicized companion dogs. These authors retold examples, ranging from obscure evidence of Ancient Egyptian pets to popular myths of Ulysses’ faithful dog Argus, to argue that this newfound human-dog relationship was timeless.

Collectively, these efforts helped transform pet dogs from beasts into friends. Reflecting their success, contemporaries affirmed that pet dogs had gained widespread acceptance in England by the mid-19th century.

Cross-Species Friends

Middle-class Victorian families generally got dogs from breeders, sellers, stores, and the streets. Pets became part of mass consumer culture for this population that had expendable income and leisure time. Strays were prevalent, and some Britons freely snatched dogs up from urban lanes.

Breeders were often genteel and concerned with pedigree. By the 1870s some popular breeders, styled as genuine-breeders, sold show dogs and purebred pets that conformed to newly created breed confirmation standards.

On the other hand, dog sellers were urban street vendors, concerned with profit, and beat away accusations that they were “dog dealers” aligned with dog nappers—a lucrative Victorian trade.

Humane reformer Mary Tealby established the world’s first animal shelter, The Temporary Home for Lost and Starving Dogs, in the London suburb Holloway in 1860.

Here, lost dogs were reunited with their middle-class families while the dogs of the poor or strays were reformed by being rehomed with a more appropriate family. One advertisement from 1863 urged anyone wanting a dog to visit since “very often valuable, and always useful Dogs are to be found here.”

One early brick-and-mortar dog store—Bill George’s Canine Castle—sold guard, working, and pet dogs to mid-century Londoners. However, pet stores remained uncommon until the 20th century.

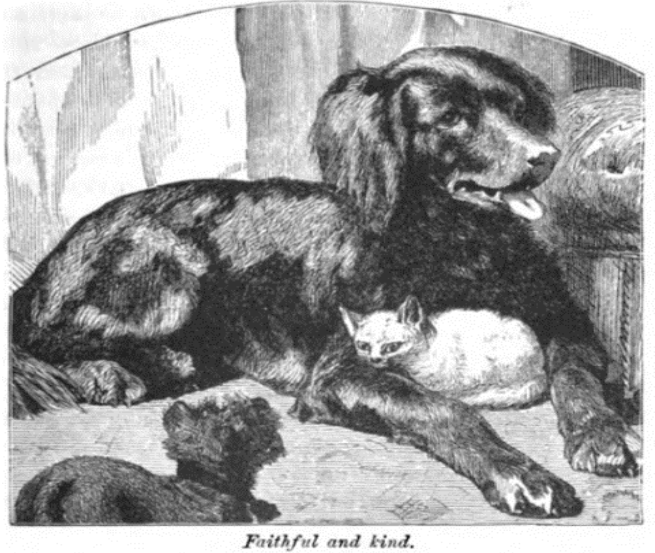

Regardless of how families got their dogs, petkeeping guidebook author Jane Loudon wrote that companionship—the family dog’s key attribute—was universal: “They are all alike in being faithful and affectionate to their masters.”

Working alongside humans was different than fitting into their nonworking lives. The Victorians attributed canine companionship to religious, social, cultural, or evolutionary rationales.

There are behavioral reasons—termed “software” by ethologists Jozsef Topal and Marta Gasci—that we now know allow dogs to uniquely bond with humans.

Coevolving alongside people for millennia honed their sociability: dogs understand hierarchical relationships, monitor human body language and auditory commands, welcome eye contact, and form bonds with numerous species and more than one organism.

Cross-species cooperation formed by decreased aggression to—and individual attachment with—humans was vital to the creation of an affectionate bond.

Although dogs possessed these abilities in the deep past, they were increasingly valued due to cultural transformations occurring in 19th-century Britain.

One of the Family

Dogs united entire families. They brought adults and children together through rearing, exercising, and playtime. In turn, families altered routines, tasks, and celebrations to allow for their dog’s participation.

A holiday jaunt to the Lake District, an overseas voyage to Continental Europe, and a Sunday trip in a motorcar became incomplete without including the family dog.

Hallowed family rituals—like Christmas and New Year’s celebrations—were enlivened after owners allowed their dogs to visit friends, exchange gifts, and pose for commemorative photographs.

Dogs also expressed family identity.

Families used their dogs to distinguish themselves, like when affixing stamps of their dog’s portrait to personal correspondence. Canine deportment reflected familial propriety. Many middle-class Victorians believed that family dogs should mirror the appropriate conduct of their children.

For example, this meant maintaining cleanliness (a child’s clean shirt mirrored a dog’s unblemished coat) and deportment (a dog not jumping on a guest reflected a child expressing the correct greeting). Evidencing their successful integration into family life, author Harriet de Salis remarked how dogs “seem to understand everything that is going on.”

Canine companionship provided unique benefits to all individuals within families.

Human-dog relationships often formed before marriage. Contemporaries affirmed how bachelors and dogs were a common duo, likely from their mutual unruly and promiscuous nature. Although these dogs were often protective of their owners, a gentle introduction to a lady typically transformed strangers into chums.

Breeder Rawdon Lee esteemed terriers as the “bachelor’s dog above all others” due to their sociability, portability, knack for indoor living, and, crucially, “he is not too boisterous for the maiden lady.” Bachelor’s dogs were to settle down since this process was believed to civilize men and their dogs.

A longing for the freedom and simplicity of youth often influenced why fathers included dogs in their families. For men with rural upbringing—especially those having grown up alongside working dogs—keeping dogs conjured up nostalgia and provided the chance to provide their children with a canine pal.

Some fathers hoped that dogs provided respite from overbearing work and an unfulfilling family life by remedying “the unsatisfied want in his own existence.”

Simple acts—like an ebullient greeting upon returning home or sitting at his feet while reading—provided relief as late-19th-century doctors affirmed how mental strain accompanied jobs staffed primarily by middle-class men.

As heads of Victorian households, fathers enforced family rules and disciplined their children and dogs. Physical reprimand through spanking or whipping was common but not universal.

The movement to stamp out animal cruelty remained incomplete and inseparable from this particular type of abuse. Physical punishment that maintained middle-class deportment among children remained permissible amidst the campaign to eliminate inhumane acts and working-class blood sports.

The domestic maternal figure was another key part of Victorian middle-class family life. Many unmarried women kept dogs—especially spaniels and poodles—that they brought later into married life (middle-class Victorians often waited to marry until their late 20s).

Mothers were the primary pet caregivers responsible for feeding, grooming, and exercising dogs in addition to administering common medical treatments. Dogs demanded unceasing care—a dog was, in Scottish physician John Brown’s words, “a perpetual baby.”

Dog owners also played with dogs alongside their children. In this way, dogs helped children and mothers bond and reaffirmed their shared place in these families. Some mothers especially recounted the joy found when watching how activities for their children, like romping in the park, became more fun once they included their furry family members.

Family dogs were affectionate, tolerant, and faithful companions for children. They provided comradery and moral instruction to impressionable minds. Author George Frederick Pardon claimed that canine selflessness would “act as a check to their [children’s] natural selfishness.”

Victorian dog owners believed that children developed a more genuine character by maturing alongside dogs. As veterinary surgeon Wesley Mills noted, “Contact with the dog is the best possible way to develop many traits of character that should be developed in all human beings.”

Mills indicated that dogs familiarized little boys and girls with “the real nature of animals … to be kind to animals, to realize that they have feeling like themselves,” and most importantly that “they are models of unselfish devotion.”

This concluding point underscored canine fidelity’s value and the hope that this hallowed attribute could rub off onto malleable humans.

Families favored breeds believed to be patient with—and protective of—children. Newfoundlands and mastiffs were popular. Children’s author Harriet Myrtle noted how a mastiff “will allow himself … to be played with by children, and even teased, without minding it.”

It was important that family dogs tolerated children and that kids learned to appropriately interact with dogs. An adverse experience might lead to a dog’s removal from the family or lead a child to develop cynophobia (the overwhelming fear of dogs).

At the same time, a child striking a dog was considered an intolerable act.

Clandestine relationships developed between children and dogs. Children often snuck morsels to dogs which, despite expressing disobedience, only strengthened the bond between dogs and kids.

Dogs were the object of children’s affection. Mothers often allowed children to help with simple tasks, like preparing food, that helped kids bond with dogs and provided early instructional steps that allowed a child to understand how to care for dogs.

Another, especially treasured connection was that dogs were faithful, affectionate, and dependable companions in old age—a time when many Britons had outlived siblings and spouses, lost friends, and lived apart from their children.

Illustrator Sydenham Edwards believed that dogs were “an excellent companion when human society is wanting,” which often coincided with advanced age.

Many Victorians echoed the belief that “the dog may especially fulfill a place of comfort in old age, when new human friends are not readily made.”

Poems from across the century remarked upon how dogs were the only companions left at the end of one’s life. In one example, poet George Crabbe stated the belief in rhyme—connecting the Victorian fears of vulnerability from bankruptcy and elderhood—that dogs remained steadfast throughout life:

“The rich man’s guardian and the poor man’s friend,

The only creature faithful to the end.”

Other Victorian Britons went so far as to suggest that only marginalized groups disliked dogs, ranging from depraved degenerates and sullen families to indigenous societies and foreign civilizations.

A Tail of Transformation

By the early 20th century, canine expert Robert Leighton believed there to be “over four million dogs in Great Britain and Ireland, or … one to every ten of the human inhabitants,” which meant that “one can nowadays seldom enter a dwelling in which the dog is not recognized as a member of the family.”

Today, there are roughly 12 million dogs in the United Kingdom, or roughly 1 per every 5 humans.

The social acceptability for keeping nonworking dogs spread outward to influence most other industrialized nations. Dogs remain the predominant—and quintessential—modern pet. The human-dog relationship that modern pet owners embrace came from transformations that occurred in Victorian Britain.

Dogs’ role in modern life not only highlights their enduring coevolutionary journey with humans but suggests that this seemingly simpler—albeit highly complex—creature possesses something that people living in many industrialized nations cannot find from their human counterparts.

Luckily for them, dogs continue bonding with people today and provide humans with their most intimate animal connections.

Grier, Katherine. Pets in America: A History. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Howell, Philip. At Home and Astray: The Domestic Dog in Victorian Britain. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2015.

Hughes, Kathryn. Catland: Louis Wain and the Great Cat Mania. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2024.

Humphrey, Neil. “In A Dog's Age: Fabricating the Family Dog in Modern Britain, 1780-1920,” PhD Dissertation. The Ohio State University, 2024.

Kean, Hilda. The Great Cat and Dog Massacre: The Real Story of World War II's Unknown Tragedy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017.

Kete, Kathleen. The Beast in the Boudoir: Petkeeping in Nineteenth-Century Paris. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

Pearson, Chris. Collared: How We Made the Modern Dog. London: Profile, 2024.

Pearson, Chris. Dogopolis: How Dogs and Humans Made Modern New York, London, and Paris. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2021.

Ritvo, Harriet. The Animal Estate: The English and Other Creatures in the Victorian Age. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 1987.

Worboys, Michael. Doggy People: The Victorians who made the Modern Dog. Manchester: University of Manchester Press, 2023.

Worboys, Michael, Julie-Marie Strange, and Neil Pemberton. The Invention of the Modern Dog: Breed and Blood in Victorian Britain. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018.