American higher education finds itself at a difficult moment. On the one hand, American colleges and universities are regarded as the finest in the world, producing new knowledge and well-trained students in more abundance than anywhere else. On the other, American higher education faces a set of challenges, some recent, some long in the making. In this essay, historians Bruce Kimball and Sarah Iler explain how we got to this point.

The years from 1950 to about 1975 have been called “The Golden Age” of higher education in the United States. During that period, the future looked bright and boundless; new campuses sprouted everywhere; and institutional wealth skyrocketed. American higher education enjoyed great esteem and prestige and was widely regarded as the best in the world.

Fifty years later, higher education has entered a Bronze Age, though gilded with huge endowments and palatial dormitories, dining services, and athletic facilities. Public favor for the some 3,300 degree-granting, non-profit colleges and universities in the United States has soured. In particular, the wealthy, elite institutions—leaders of higher education throughout the world—are under siege.

How and why did this happen?

The shift in public opinion has recently been attributed to several factors, including the demographic decline of college-age students, a failure to respond to students’ vocational interests, and a populist reaction against the “woke-ness” of higher education. But those explanations overlook deeper historical origins and fundamental sources of the animus.

In fact, the shift is rooted in financial developments that arose in the late 19th century, unfolded during the 20th century, and ignited resentment by the early 21st century.

In particular, four developments occurred concurrently, and each involved a number of issues that lately have drawn attention.

First was the growth and stratification of wealth, or “endowment”—the financial capital that is held permanently and invested by colleges and universities to yield an annual, independent source of income. Endowment size has served as a proxy for academic excellence and prestige.

Once universally celebrated, large endowments have prompted paradoxical attempts to exploit these invested funds either by taxing their returns or by divesting to show support for favored causes. Endowments are also targeted because they have become steeply stratified over the past century. Merely one-fifth of the some 3,300 colleges and universities today own about 99 percent of all permanently invested funds.

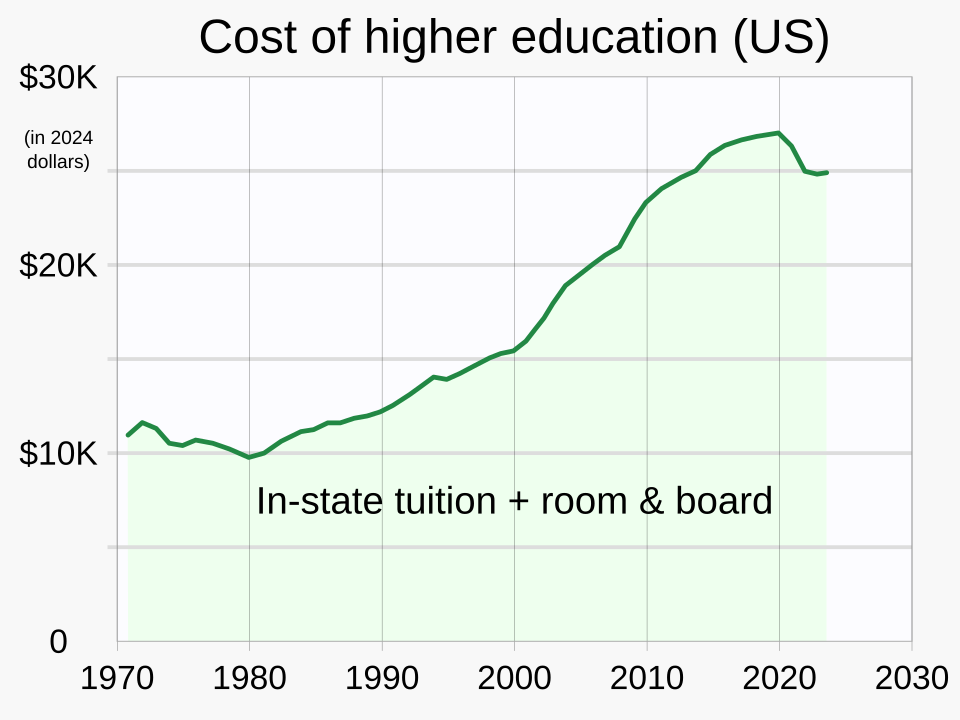

The second development was the growing hunger for revenue in higher education. Apart from endowment income, this desire for revenue inspired new forms of fundraising, as well as the pursuit of grants and government subsidies. Tuition hikes also seemed to manifest the incessant drive for revenue and prompted complaints, particularly as student debt rose dramatically. Why do colleges and universities continually seek more?

Third, the cost for institutions to produce the education rose dramatically. The average total production cost per student has escalated faster than the cost of living, and economists, policymakers, and politicians have alternately absolved or blamed higher education.

Finally, the drive for revenue ignited fierce competition among the richest colleges and universities, which came to view their rivalry as normal, necessary, and even virtuous. In the late 20th century, this intense rivalry ignited resentment because the wealthy elite institutions appeared insatiable, even as they served as exemplars of higher education.

In this essay, we explain the history of these four financial developments that ultimately shifted public opinion of higher education from esteem and appreciation in the Golden Age to criticism and resentment in the Gilded Bronze Age of the early 21st century.

I. Wealth and Stratification

The roots of these four developments lie in the formative era of American higher education between 1870 and 1930.

Before the Civil War, the economy of the United States did not produce enough surplus personal wealth to support huge benefactions, and most gifts to higher education went to support current operations or to construct buildings.

Between 1870 and 1930, new industrial enterprises fueled unprecedented economic growth and created multimillionaires for the first time in American history. Upon retiring, many of these industrialists contributed to an enormous flood of philanthropy, and “the great bulk” of the “permanent endowments” established by philanthropists went to colleges and universities, reported Henry S. Pritchett, the president of the Carnegie Endowment for the Advancement of Teaching, in 1929.

Growth of Endowments and Stratification

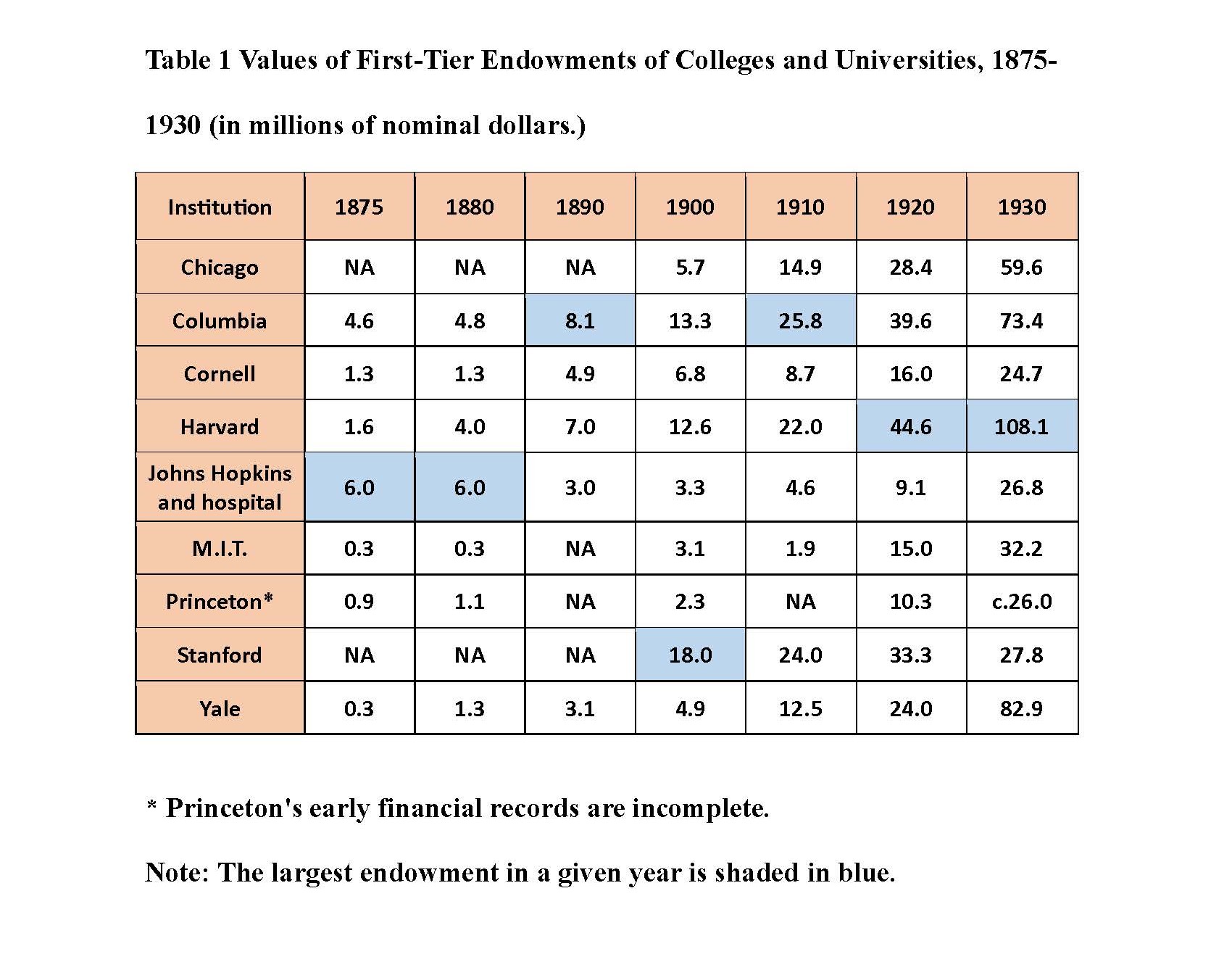

Combined with state appropriations and federal land grants, the new philanthropy increased the aggregate permanent funds of higher education forty-fold between 1870 and 1926. This remarkable growth is exemplified in the permanent funds of the top tier of wealthy universities (Table 1).

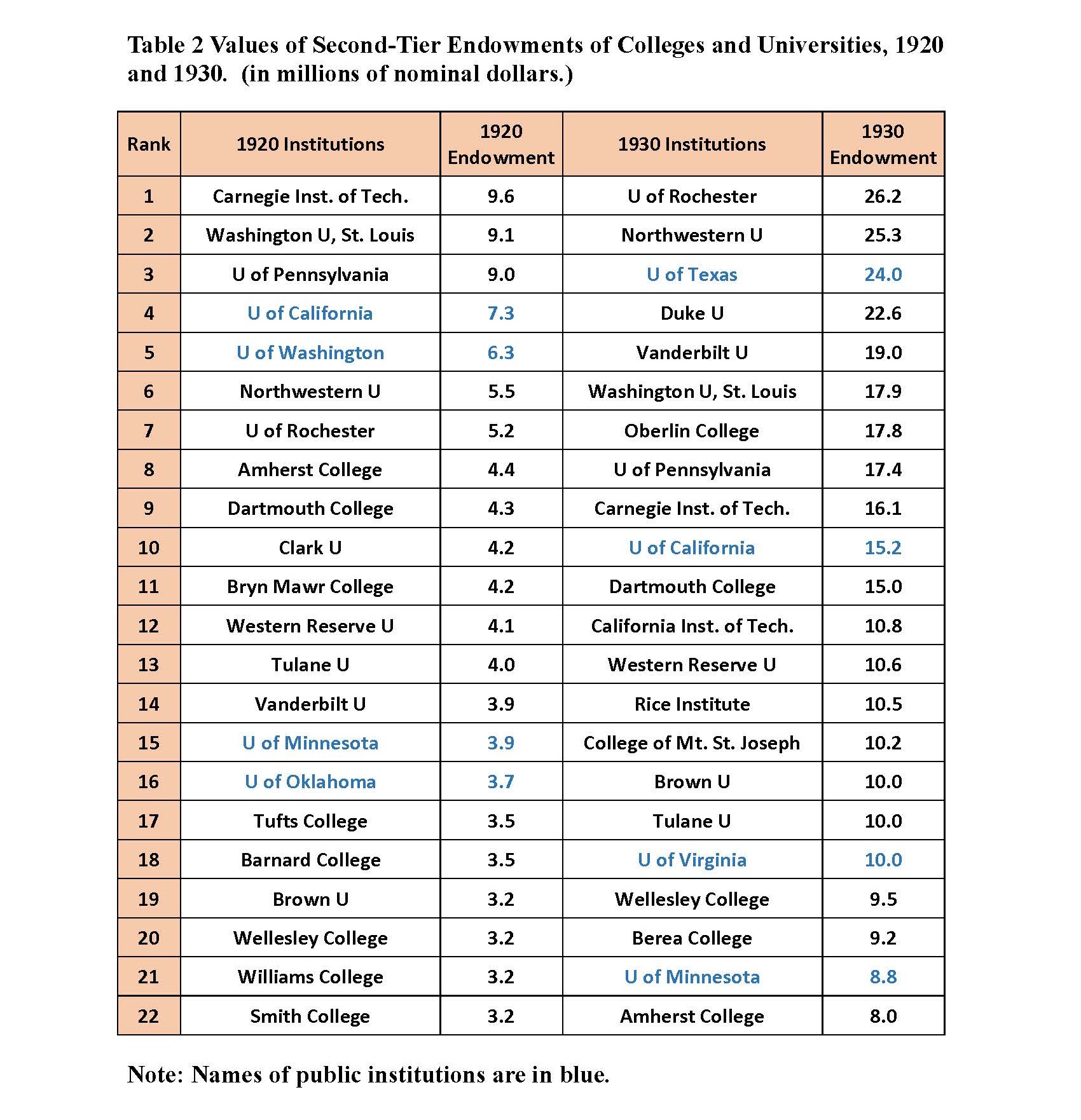

By 1920, a second tier of about 22 wealthy colleges and universities had formed, demonstrating that significant stratification of financial capital in higher education had begun. The composition of the second tier fluctuated with changes in endowment values during the 1920s (Table 2).

Prior to 1870, colleges and universities were rarely listed by endowment size because amounts of principal and income were too small to matter in distinguishing schools. In the following decades, marked distinctions among the wealth of colleges and universities started to emerge, and the stratification widened subsequently.

The second stage in the emergence of endowment was a growing appreciation for the benefits of permanent funds, followed by deliberate efforts to enlarge them. These closely related developments were led by President Charles W. Eliot of Harvard and Trevor Arnett, secretary and then president of the General Education Board.

One might expect that Harvard had the largest endowment during the formative era, since it was the oldest college and had the longest time to invest its permanent funds. But Table 1 reveals that it was not until 1920 that Harvard attained the lead among endowments that it has maintained through today, a century later.

How did Harvard gain that lead? Not by banking huge gifts, but by pursuing a novel financial strategy conceived by Eliot during his 40-year administration from 1869 to 1909.

The core of the strategy was to prioritize permanent funds and to direct all financial policies toward increasing them. No other university adopted this novel strategy during Eliot's tenure, and the university's endowment surged ahead by 1920.

Meanwhile, John D. Rockefeller founded the General Education Board (GEB) in 1903 and donated the equivalent of more than $3.5 billion in 2025 dollars over the next 16 years to fund it. The GEB focused on increasing the number and size of endowments in higher education, under the leadership of Arnett, who came to the GEB from the University of Chicago in 1920 and published the leading guidebook on college and university finance in 1922.

During the 1920s, scholars began studying endowments and found that larger endowments grew faster than small endowments. One reason was that philanthropists gave wealthy schools more money, believing that they were more successful and deserving. Another reason was that larger endowments earned higher rates of return than smaller endowments because wealthier schools could afford to hire better financial advisors.

Already, rich schools were getting richer faster, increasing the stratification by wealth. But the differences among the strata were still relatively small because the investing strategy was uniformly conservative, and annual yields were fairly similar.

Aggressive Investment Strategies Increase Stratification

Conservative, risk-averse investing had predominated in higher education from the beginning of the colonial period. Before 1900, portfolios consisted almost entirely of mortgages, promissory notes, bonds, and real estate that could be rented or farmed.

During the first half of the 20th century, some trustees and treasurers began investing in corporate stocks, but such allocations rarely reached 20 percent in even the most aggressive portfolios.

After 1950, portfolio management took three major steps to assume more risk and become more aggressive. At the same time, higher education became increasingly stratified by wealth because many treasurers and trustees feared taking on more risk, and the growth of their endowments lagged behind.

First, in 1951, Harvard Treasurer Paul Cabot raised the target allocation of corporate stocks in the university’s portfolio to 60 percent and lowered the target of bonds to 40 percent. Though regarded as conventional today even for individuals, Cabot's 60/40 portfolio was revolutionary at the time.

Other colleges and universities hesitated to follow, including wealthy ones such as Yale, Columbia, and MIT. During the 1950s and 1960s, Harvard’s endowment outperformed nearly every other in higher education.

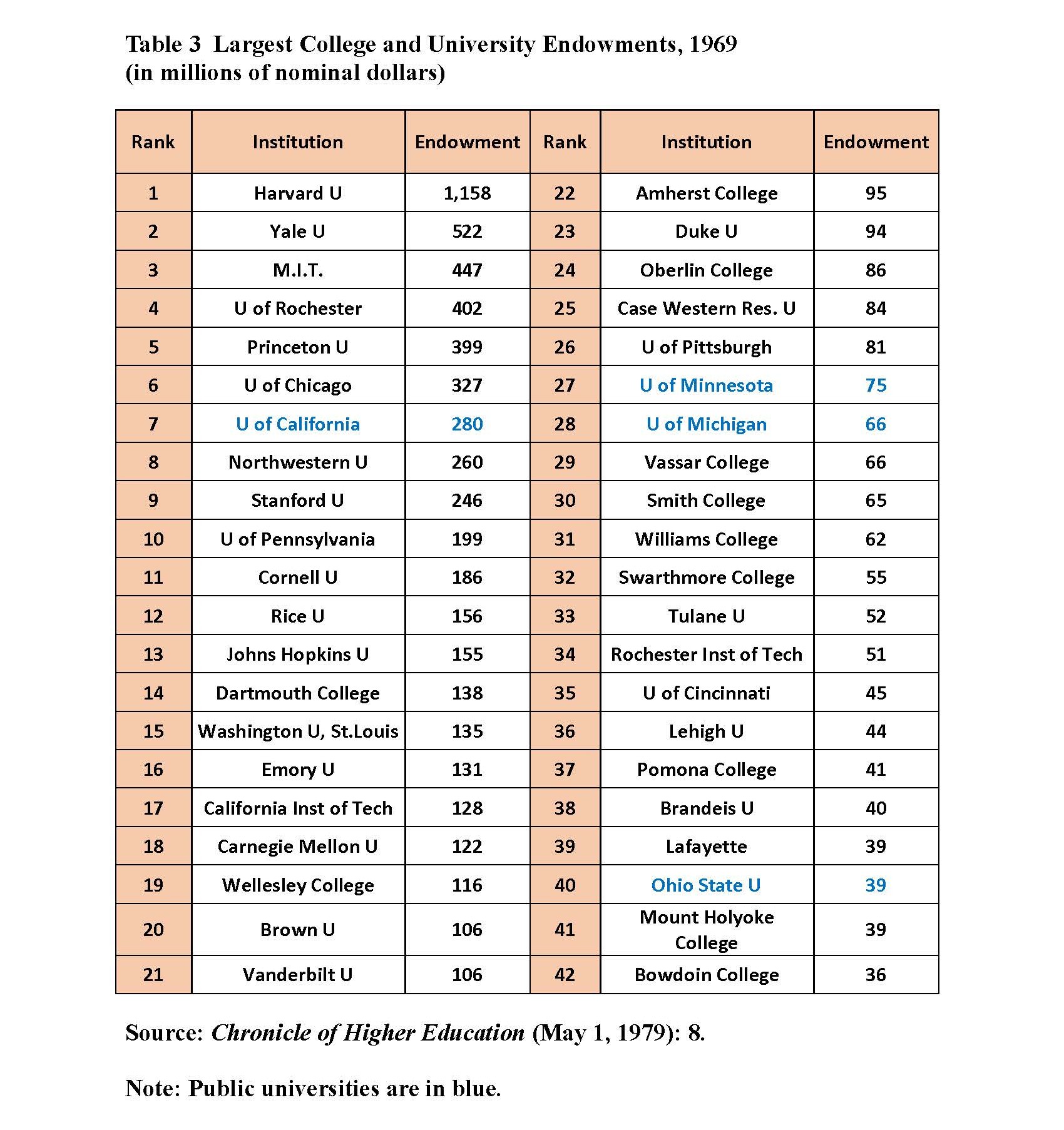

By 1970, Harvard had cemented its top rank, as seen in the first public listing of endowments in higher education, which appeared in the Chronicle of Higher Education. The largest endowments at the time are presented in Table 3.

The second step occurred during the 1970s, even though the nation slipped into a decade of “stagflation,” that is, stagnant growth and steep inflation coupled with high unemployment. Encouraged by the Ford Foundation, a few wealthy colleges and universities began to replace “value stocks” (of large companies paying high dividends) with risky “growth stocks” (of small companies having high potential for growth).

This risky strategy yielded massive returns in the 1980s and 1990s. But, as before, treasurers and trustees of most colleges and universities feared assuming more risk in their portfolios. For example, many land-grant institutions were still primarily invested in bonds. Endowment portfolios excluding growth stocks fell further behind, widening the stratification.

Third, in the 1990s, Yale’s Chief Investment Officer, David Swensen, developed a model of investing in extremely risky “alternative assets,” which include hedge funds, private equity, and “real assets,” that is, natural resources.

An investor must wait several years, even decades, to harvest the return on alternative assets, and the risk is much greater than stocks. Only schools with the largest endowments could afford to diversify their portfolios and assume the huge, short-term risk of alternative assets.

But the long-term reward is much greater. The annual return on Yale's endowment under Swensen exceeded virtually all others through 2007.

In the 2020s, the largest endowments, boosted by alternative assets, reached astronomical amounts in the tens of billions. Richer schools became richer even faster, and higher education became more steeply stratified by wealth.

Of the some 3,300 colleges and universities today, the top 25 have endowments exceeding $7 billion (Table 4), and those 25 own about half of the permanent invested funds in higher education.

II. Hunger for Revenue

Even as endowment size and annual yield rapidly increased—at least for the wealthiest and most aggressively invested—colleges and universities hungered for more operating revenue throughout the 20th century.

Three kinds of revenue mattered most: fundraising, government grants and subsidies, and tuition, which seemed to increase student debt.

New Forms of Fundraising

Public fundraising is so rampant in higher education today that it is hard to imagine a time when colleges and universities did not openly solicit donations. It is even more difficult to conceive that many presidents resisted doing so in the early 20th century. Even the presidents of Yale and Columbia believed that publicly “begging” for money was undignified, like asking for charity. They preferred to appeal privately to wealthy donors.

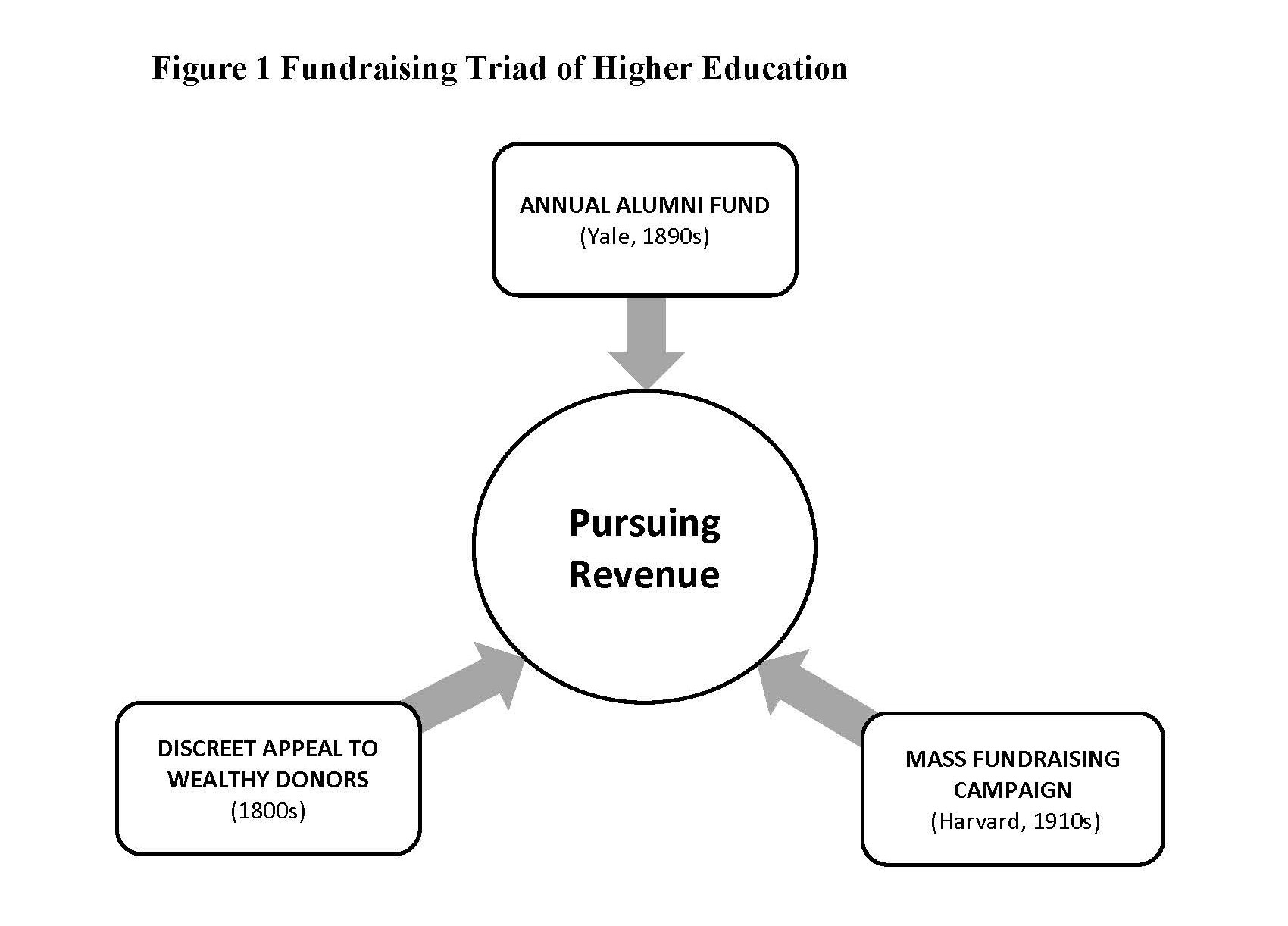

Yet innovation in fundraising occurred despite a president’s lack of cooperation. Yale alumni invented the annual canvass of alumni for donations in the 1890s. They justified this innovation as “democratic” in contrast to the traditional “aristocratic” mode of discreetly asking only wealthy donors for large gifts. By 1930, about 150 colleges and universities had adopted the new “democratic” practice, including state universities and HBCUs from California to Vermont.

Meanwhile, inspired by novel initiatives at the women’s colleges of Smith and Wellesley, Harvard alumni in 1915 introduced the first national multi-year fundraising campaign, administered by paid staff.

By 1920 at least 75 colleges and universities were running public campaigns based on the Harvard model and seeking more than $3 billion in 2025 dollars. Then, in 1925, just as the first novel drive was ending, the Harvard administration initiated a new drive by appealing discreetly to wealthy donors.

Thus commenced the now conventional fundraising triad in higher education, depicted in Figure 1.

Traditional discreet appeals to wealthy donors and foundations continue; alumni canvassing operates annually; large fundraising campaigns run concurrently; and planning for a new public drive begins as soon as the prior one ends. In such campaigns, about 10 percent of the donors consistently give about 90 percent of the funds raised.

Government Grants and Subsidies

During the 1930s and 1940s, fundraising naturally slowed amid the Depression and World War II. Then, in the 1950s, another new revenue source emerged, when huge federal grants and contracts began to flow to universities.

However, the bulk of this revenue during the Golden Age went to just 25 elite universities, and supported research in defense, medicine, and advanced natural sciences. These federal grants did not directly support “educational” expenses—the production cost of educating students, particularly undergraduates.

In fact, in the closing decades of the 20th century, federal grants began to drain universities’ resources, as the amount of overhead paid by grantors fell dramatically. The trend continued in the 21st century, belying the impression that research grants were enriching higher education.

Federal support for the production cost of educating students came primarily from legislative appropriations, such as the G.I. Bill (1944), National Defense Education Act (1957), Higher Education Facilities Act (1963), and Higher Education Act (1965).

Yet the oldest and strongest continuing source of direct government support was state-level subsidies, beginning in the 1870s.

After a century, however, the proportion of production cost paid by state subsidies began to decrease during the stagflation of the 1970s, and continued to fall for the next four decades (Table 5).

Tuition and fees rose after 1980 to cover the shortfall, particularly in the public sector. The burden of paying the production cost of higher education shifted from the nation’s taxpayers to the individual student, as economists have observed.

Tuition

Tuition and fees are often likened to prices in business, which are set by a markup over expenses. But in higher education, revenue from tuition and fees has always paid less than half of the cost to produce students’ education, and usually less than a third of that production cost, depending on the era and the sector of higher education.

Before 1970, all students paid the full list price of tuition, even if partly funded through a scholarship, and schools received all the tuition revenue that they charged. Then came the stagflation of the 1970s, when the relative value of all subsidies declined. Listed tuition, or price, rose to compensate for the shortfall.

To maintain enrollment levels, a few private colleges and universities introduced a radical new tactic. They began to discount tuition, that is, to cut the list price for certain students whom they wished to enroll.

The price cut was disguised as an “institutional grant” that schools gave back to students. But students were actually paying a “net price”: the listed tuition minus the price cut. The “institutional grant,” or price cut, amounted to lost tuition revenue for the school.

During the 1980s and subsequently, tuition discounting proliferated rapidly, particularly at private colleges and universities, which competed to attract the best students, diversify the student body, or simply fill their seats. The frequency and amount of tuition discounting are difficult to calculate because most schools do not publish the data. But it is clear that discount rates continued to increase in the twenty-first century (Table 6).

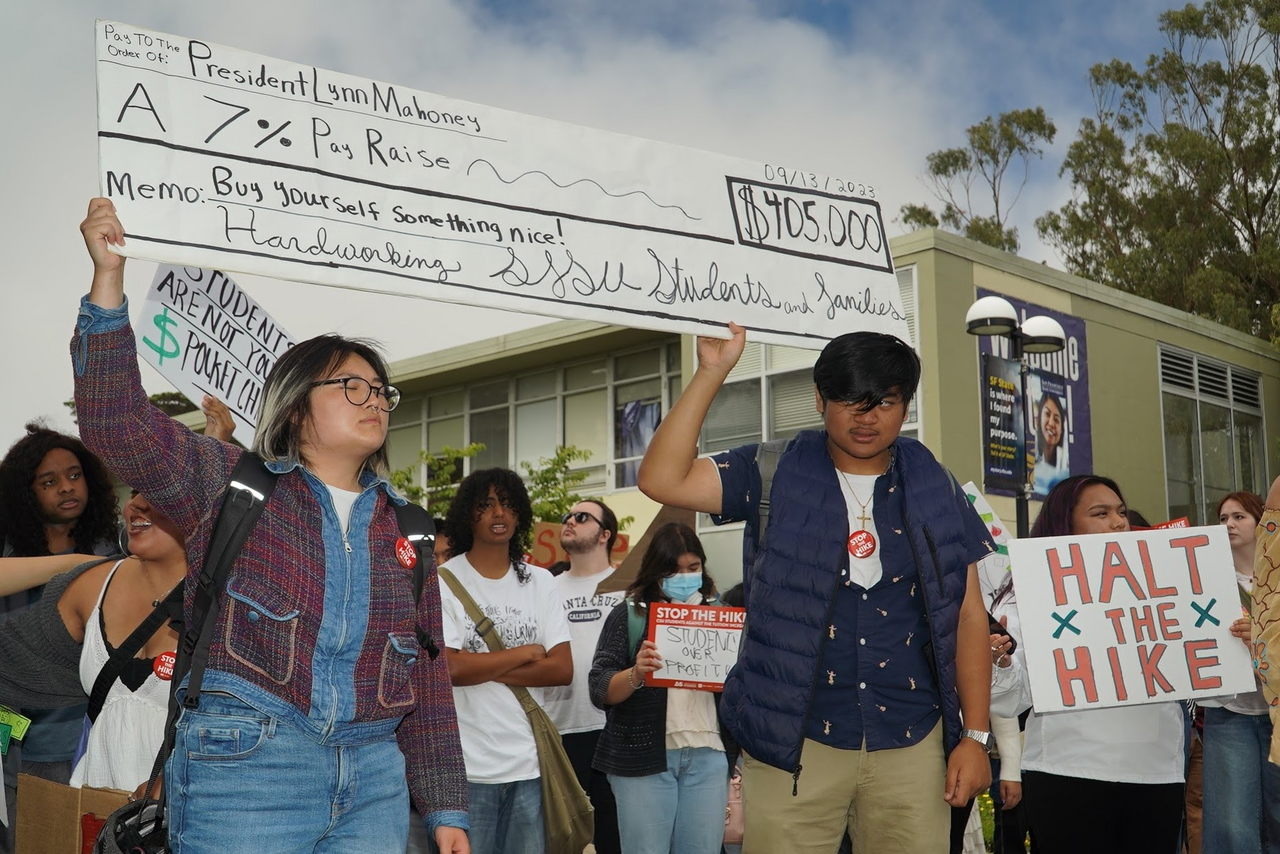

Schools that discounted tuition were therefore caught in a whipsaw. Hikes in list tuition spawned widespread criticism. Yet students on average were not paying more in tuition, and schools did not receive more tuition revenue unless their enrollment increased.

The paradox culminated in the early 21st century. The average net price paid by undergraduates at both public and private four-year institutions held steady in constant dollars between 2006 and 2020, while the average list price of tuition and fees increased by 16 percent in constant dollars between 2010 and 2020 at those schools.

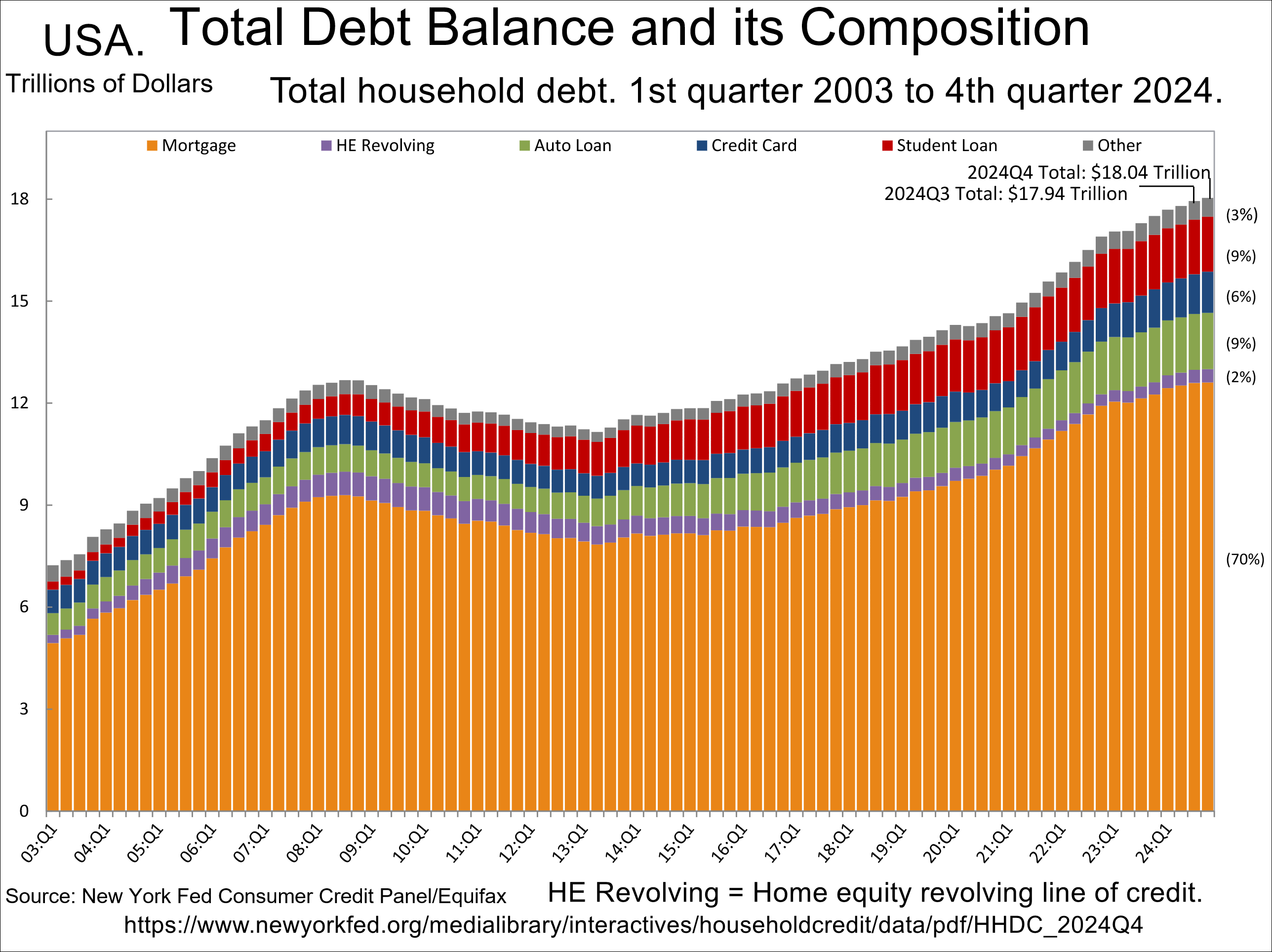

Student Debt and Total Price

As list tuition rose, aggregate student debt ballooned to about $1.7 trillion by 2020, inciting public resentment and prompting legislative proposals designed to force colleges and universities to reduce student debt. To evaluate such proposals, it is important to understand the different kinds of debt.

About half the debt is owed by students who chose to attend graduate and professional schools, including in the fields of medicine, law, and business.

Another quarter of the debt is owed by undergraduates who attended for-profit colleges and universities. Many of these schools are predatory. Their students generally owe the largest amounts of debt and also have the highest default rates.

The last quarter of the debt is owed by students of greatest concern to non-profit, degree-granting colleges: their undergraduates. More than 60 percent of this debt is owed by students from middle-class or working-class families whose wages and salaries have not kept pace with the cost of living over the last forty years.

Yet this burdensome debt is due neither to the rising list tuition nor to the discounted net price, which has plateaued for most of the last two decades.

Rather, these undergraduates have assumed debt to pay for ancillary expenses—room, board, clothing, books, technology, travel, recreation, entertainment, and so forth—which have grown faster than the cost of living.

The total price paid by students has thus spiraled higher, generating debt and resentment.

III. Production Cost and Competition

Apart from the total price that students were paying, the total production cost that schools were bearing grew even faster because colleges and universities were also expanding their administration and support services. Some of these were required by government regulation, such as the Americans with Disabilities Act. But many were optional, including the expansion of legal staff, administrative staff, maintenance, security, career services, counseling services, and other support services.

The average, total, per-student production cost of higher education, excluding medical centers, has been rising faster than the cost of living since 1970.

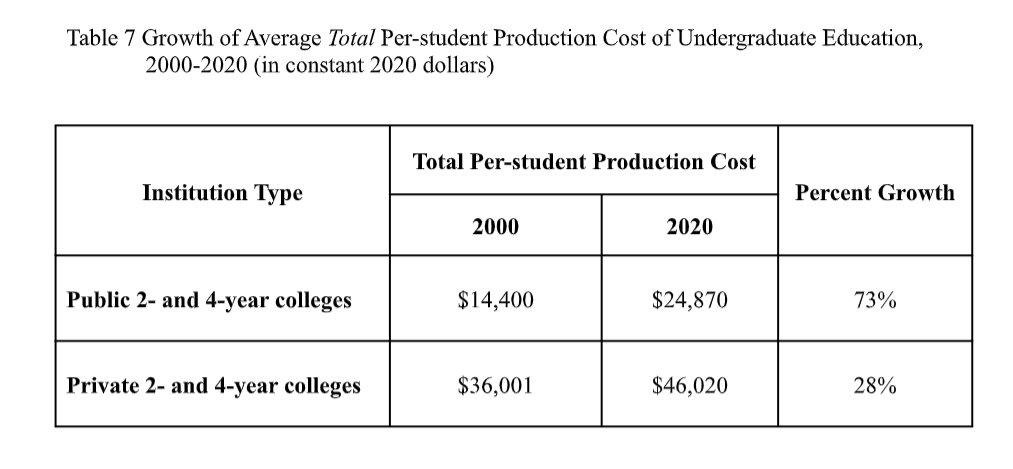

In the first two decades of the 21st century, the total per-student cost has continued to rise, as shown in Table 7. The difference in growth between the private and public sectors is largely due to the proportional decline in state subsidies for public institutions and the growth of endowment yields in the private sector.

Why do colleges continue to increase both ancillary expenses charged to students and ancillary costs in administration and support services? The fundamental and generally accepted explanation is two-fold.

On the one hand, colleges and universities have acted like most charitable, ecclesiastical, and social service organizations. They believe that their financial need is infinite because additional revenue can always be put to good use.

On the other hand, and in addition to that benign motive, competition to recruit students and to increase their prestige and influence fuels the insatiable need for more funding.

Every college and university has therefore become “engaged in the equivalent of an arms race of spending to improve its absolute quality and . . . its relative stature in the prestige pecking order.” This arms race is most intense among the wealthiest, elite schools. Their exemplary status has then stoked the competition for revenue throughout higher education.

IV. “Our Greedy Colleges”

Taken together, the immense growth of endowments, the widening stratification of institutional wealth, the incessant cycle of fundraising, the steep increase in listed tuition, and the expansion of production costs for ancillary services and administration began to ignite resentment about “our greedy colleges” during the administration of President Ronald Reagan in the 1980s.

By the beginning of the 21st century, these factors triggered “intense scrutiny and criticism” of higher education.

Early in the 21st century, bipartisan Congressional committees began to scrutinize the rising wealth, cost, and price of higher education. Then, in 2017, Congress passed the Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA) that imposed an unprecedented excise tax on the endowment income of the wealthiest, private, non-profit colleges and universities.

In 2023, 56 schools were subject to the tax and paid a total of about $380 million in excise taxes. Increases in the excise tax are under consideration.

Elected officials nationwide are thus scoring political points by denigrating the crown jewels of American higher education. The success of their criticisms reflects the public ire that had been building against higher education—especially the wealthy, elite institutions—during the prior four decades, and culminated the prior century of financial developments explained above.

But TCJA did not have to happen. Wealthy elite schools could have alleviated public criticism and resentment by ending their financial arms race and adopting a new financial strategy of cooperation rather than competition.

These institutions can still pursue this strategy and rebuild public esteem and political favor by sharing their endowment income with needy school systems, colleges, and universities.

Doing so would contribute more to the public good than a punitive excise tax because the wealthy elite schools, we believe, would spend the amount of their excise tax much more effectively and efficiently than the federal government. A few schools have begun to do this, such as the University of Pennsylvania.

In general, however, the wealthiest elite schools appear to have forgotten their foundational purposes and are persevering in intense competition to acquire more money and prestige, which serves as a proxy for academic excellence. And that is why we call our current era the Gilded Bronze Age of Higher Education.

Tables 1-7 and Figure 1 are all courtesy of the authors.

“2024 Nacubo-Commonfund Study of Endowments.” NACUBO. February 12, 2025, https://www.nacubo.org/Research/2024/NACUBO-Commonfund-Study-of-Endowments.

“2024 Tuition Discounting Study.” NACUBO. October 8, 2024, https://www.nacubo.org/Research/2024/NACUBO-Tuition-Discounting-Study.

American Council on Education. “Understanding College and University Endowments: Answers to Commonly Asked Questions Regarding the Purpose. History, and Functionality of Endowments.” 2024, https://www.acenet.edu/Documents/Understanding-College-and-University-Endowments.pdf.

A.J. Angulo. Diploma Mills: How For-Profit Colleges Stiffed Students, Taxpayers, and the American Dream. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016.

Trevor Arnett. College and University Finance. New York General Education Board, 1922.

Michael N. Bastedo, et. al., ed. American Higher Education in the Twenty-First Century: Social, Political, and Economic Challenges. Fourth Edition. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016.

William J. Bennet. “Our Greedy Colleges.” New York Times. February 18, 1987, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1987/02/18/623887.html?pageNumber=31.

Collin Binkley, “More Than 50 Universities Face Federal Investigations as Part of Trump’s Anti-DEI Campain.” AP, March 14, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/trump-dei-universities-investigated-f89dc9ec2a98897577ed0a6c446fae7b.

William G. Bowen and David W. Breneman. “Student Aid: Price Discount or Educational Investment?” The Brookings Review. 11, no. 1 (1993): 28.

Megan Breeman. “Americans’ Confidence in Higher Education Down Sharply.” Gallup, Jul 11, 2023, https://news.gallup.com/poll/508352/americans-confidence-higher-education-down-sharply.aspx.

Hilary Burns, “Too Much Student Debt? Or Too Many Students in College? Conservatives Take Aim at Higher Education.” Boston Globe. December 18, 2024, https://www.bostonglobe.com/2024/12/18/metro/conservatives-students-college-debt-enrollment/

College Board. “Trends in College Pricing.” 2009, College Board, Trends in College Pricing 2009.

College Board. “Trends in College Pricing and Student Aid. 2020, College Board, Trends in College Pricing and Student Aid 2020.

Colleen Cordes. “Lower Overhead Costs.” Chronicle of Higher Education, 40 no. 16 (1993), https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ476048.

Alisa F. Cunningham et. al. “Study of College Costs and Prices, 1988-89 to 1997-98.” National Center for Education Statistics, 2001, https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED462047.

Ronald G. Ehrenberg. Tuition Rising: Why College Costs So Much. Harvard University Press, 2002.

Ronald G. Ehrenberg, ed. What’s Happening to Public Higher Education? The Shifting Financial Burden. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008.

Richard M. Freeland. Academia’s Golden Age: Universities in Massachusetts, 1945-1970. Oxford University Press, 1992.

Lee Gardner. “Plans to Hike the College-Endowment Tax are Taking Shape. They’re Not What You’d Expect.” Chronicle of Higher Education. March 10, 2025, https://www.chronicle.com/article/plans-to-hike-the-college-endowment-tax-are-taking-shape-theyre-not-what-youd-expect?utm_source=Iterable&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=campaign_12883190_nl_Academe-Today_date_20250313.

Andrew Gillen. “Trends in Higher Education: State Funding and Tuition Revenue at Public Colleges from 1980 to 2023.” Cato Institute. November 14, 2024, https://www.cato.org/briefing-paper/trends-higher-education-state-funding-tuition-revenue-public-colleges-1980-2023.

Bruce A. Kimball. “Book Review Essay.” The Journal of Higher Education 86, no. 1 (2015): 156–70.

Bruce A. Kimball. “‘Democratizing’ Fundraising at Elite Universities: The Discursive Legitimation of Mass Giving at Yale, Harvard, 1890-1920. History of Education Quarterly, 55, no. 2 (2015): 164-189.

Bruce A. Kimball. “The First Campaign and the Paradoxical Transformation of Fundraising in American Higher Education, 1915–1925.” Teachers College Record, 116, no. 7 (2014): 1-44.

Bruce A. Kimball. “The Rising Cost of Higher Education: Charles Eliot’s ‘Free Money’ Strategy and the Beginning of Howard Bowen’s ‘Revenue Theory of Cost,’ 1869—1979.” The Journal of Higher Education 85, no. 6 (2014): 886–912, doi:10.1080/00221546.2014.11777351.

Bruce A. Kimball and Sarah M. Iler. “The Case Against Any Divestment, Ever.” Inside Higher Ed. May 28, 2024, https://www.insidehighered.com/opinion/views/2024/05/28/case-against-any-divestment-ever-opinion.

Bruce A. Kimball and Sarah M. Iler. “Rising Production Cost—and Rising Resentment.” Inside Higher Ed. December 18, 2022, https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2022/12/19/why-production-cost-and-resentment-rising-opinion.

Bruce A. Kimball and Sarah M. Iler. “Share the Wealth.” Insider Higher Ed. March 1, 2023, https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2023/03/02/it%E2%80%99s-time-wealthy-colleges-share-wealth-opinion.

Bruce A. Kimball and Sarah M. Iler. Wealth, Cost, and Price in American Higher Education. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2023.

Bruce A. Kimball and Benjamin Ashby Johnson. “The Beginning of ‘Free Money’ Ideology in American Universities: Charles W. Eliot at Harvard, 1869-1909.” History of Education Quarterly, 52, no. 2 (2012): 222-250.

Bruce A. Kimball and Jeremy B. Luke. “Historical Dimensions of the ‘Cost Disease’ in US Higher Education, 1870s-2010s. Social Science History, 42 no. 1 (2018): 29-55.

Adam Looney, David Wessel, and Kadija Yilla. “Who Owes All That Student Debt? And Who’d Benefit If It Were Forgiven?” Brookings. January 28, 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/policy2020/votervital/who-owes-all-that-student-debt-and-whod-benefit-if-it-were-forgiven/.

Vimal Patel and Sharon Otterman. “Colleges Wonder if They Will Be ‘The Enemy’ Under Trump.” New York Times. November 12, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/11/12/us/trump-higher-education-policy-universities.html.

Michael B. Paulsen and John C. Smart, ed. The Finance of Higher Education: Theory, Research, Policy, and Practice. Agathon Press, 2001.

“Penn Pledges $100 Million to the School District of Philadelphia. Upenn.edu. November 17, 2020, https://penntoday.upenn.edu/news/penn-pledges-100-million-school-district-philadelphia.

George Putnam, “Sound Investing: A Brief Comparison of the Financial Policies of Five Eastern Universities,” Harvard Alumni Bulletin, May 9, 1953, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000499743.

Stephanie Sual and Alan Blinder. “As Trump Targets Universities, Schools Plan a Counteroffensive.” New York Times. January 29, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/29/us/trump-targets-universities-schools-plan-counteroffensive.html?searchResultPosition=2.

David Swensen. Pioneering Portfolio Management: An Unconventional Approach to Institutional Investment. Free Press, 2009.

Ways and Means. Bill, Congress.gov § Public Law No. 115-97 (2017), https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/1/text.

“What if the Tax Treatment of College and University Endowments?” Tax Policy Center. January 2024, https://taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/what-tax-treatment-college-and-university-endowments.

J. Peter Williamson. Funds for the Future: Report of the Twentieth Century Fund Task Force on College and University Endowment Policy. Institute of Education Science, 1975.

Megan Zahneis. “Research Universities Are Poised to Lose Billions Under Trump’s Sudden Cut.” Chronicle of Higher Education. February 8, 2025, https://www.chronicle.com/article/research-universities-are-poised-to-lose-billions-under-trumps-sudden-cut.