On November 8-9, 1923, at a local beer hall in Munich, Germany, Adolf Hitler and General Erich Ludendorff led an ill-fated attempt to overthrow the Bavarian government and establish a new nationalist regime. Often cited as a watershed moment in the rise of National Socialism, Hitler’s brazen plan to overthrow the Weimar government has been scrutinized for its audacity, its failures, and what it foretold for Germany's future.

Yet, as we look back, it is time we consider a less-explored aspect of this pivotal event: not as a failed putsch, but as a confirmation of the resilience of the Weimar Republic, a system so robust that it withstood numerous adversities, from economic turmoil to political unrest.

The year 1923 was indeed a crucible for the fledgling German Republic. Delinquent on World War I reparation payments required by the Treaty of Versailles, Germany faced the punitive occupation of the Ruhr by Franco-Belgian forces, stoking nationalist resentments.

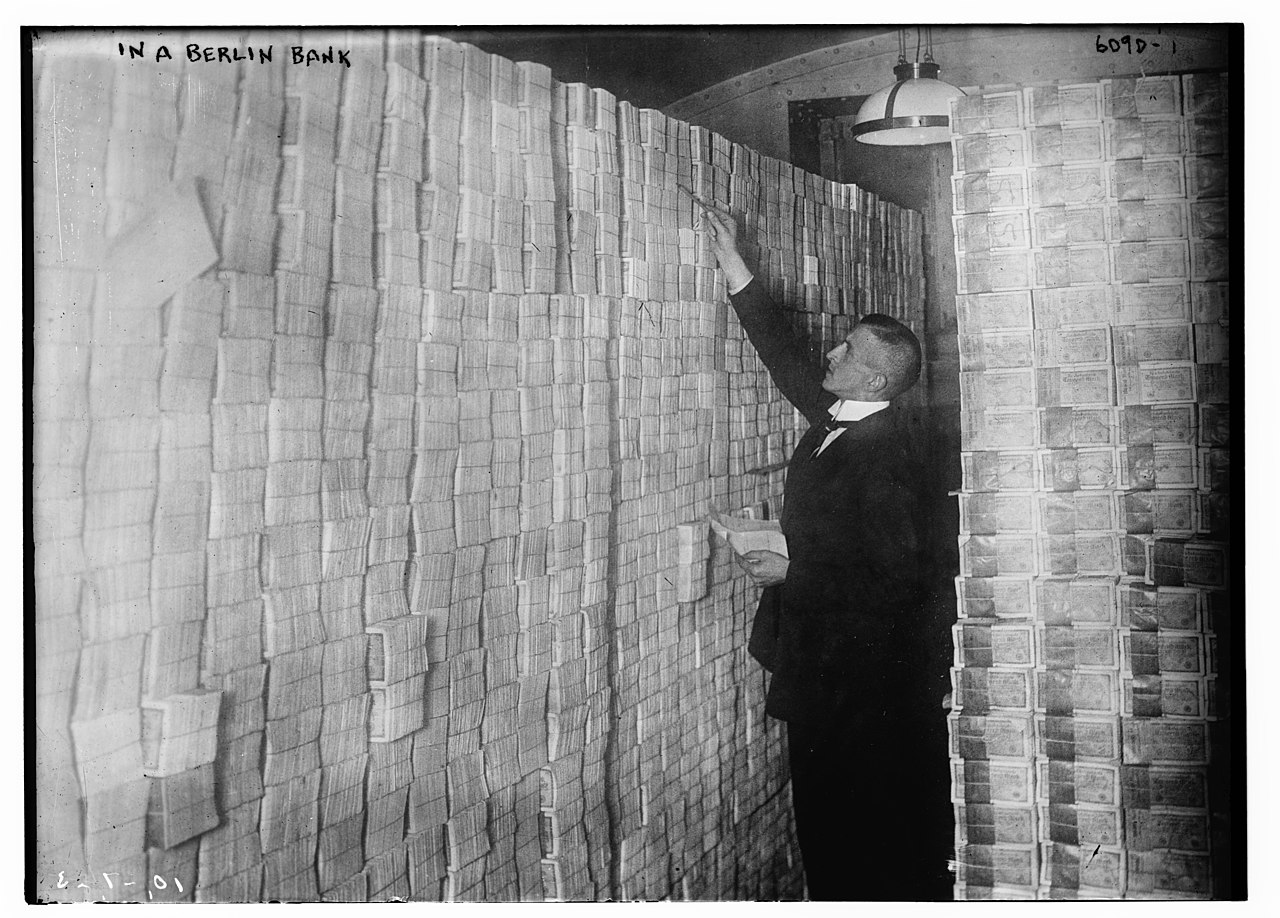

The economy, already in shambles, plunged steadily into hyperinflation, eviscerating the savings of millions. The eight-hour workday, a cherished promise to Germany’s working class that stood out as one of the few tangible victories of Weimar democracy, was revoked.

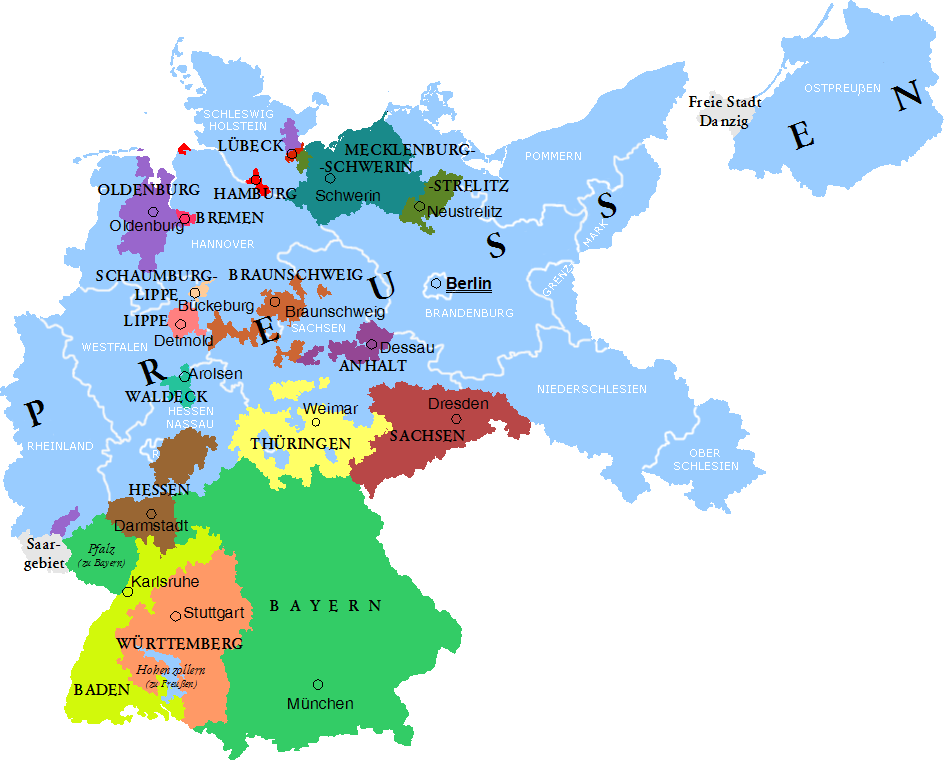

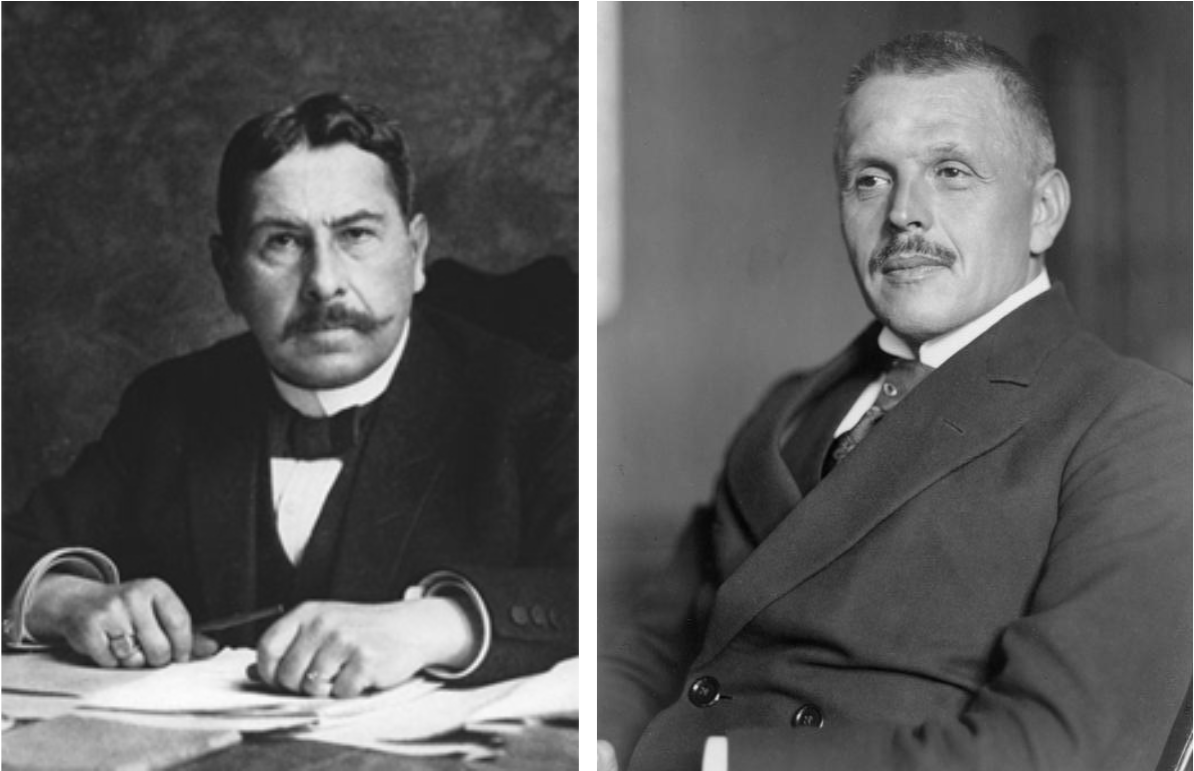

In August, Chancellor Wilhelm Cuno’s resignation gave Gustav Stresemann the unenviable task of steering a beleaguered nation through these crises. Just one month later, as “vigilante” assassinations and political violence destabilized the nation, Bavaria appointed Gustav Ritter von Kahr as State Commissioner General (Generalstaatskommissar), granting him emergency dictatorial powers. Through this appointment, Bavaria symbolically condemned the Weimar government’s perceived passive acceptance of the Ruhr occupation.

Kahr was a right-wing conservative politician who sympathized with the nationalist movements that had grown since the end of the World War I and was keen to topple the government in Berlin. Once in power, he immediately repealed laws designed to safeguard the republic from anti-democratic organizations, including legislation that had prevented these groups from sharing printed material or assembling with the intent to conspire against the existing government.

Following Kahr’s example, the Minister of Defense (Reichswehrminister), Otto Gessler, attained similar emergency powers over the German military. As Minister of Defense, Gessler was aware of the need to maintain order and unity within the German military, especially given the volatile political landscape.

While Kahr was busy repealing laws in Bavaria, Lieutenant General Otto von Lossow, high-ranking officer of the German armed forces (Reichswehr), defied orders from Berlin to suppress those same right-wing organizations. Lossow joined in alliance with Kahr and the commander of the Bavarian police, Hans von Seisser, to form a “triumvirate” in Munich to govern the region.

The triumvirate spent the next few months scheming to mobilize the Bavarian military and far-right nationalist groups in a “March on Berlin,” drawing inspiration from Italian fascist leader Benito Mussolini’s successful “March on Rome.”

Amidst growing dissent, Gessler found himself caught in a difficult position: enforcing Berlin’s edicts could exacerbate already fragile relations with Bavarian authorities, while giving in would signal weakness.

It seemed that the Weimar Republic was on its knees, beset from all sides by economic, political, and social crises. In terms of timing, the conditions for a successful coup d’état seemed to be perfect. Yet the resilience of the republic proved itself at precisely this moment.

When all that remained of the Weimar democracy was the allegiance of key individuals, Hitler and Ludendorff led their attempted coup. As Kahr was giving a speech at the Bürgerbräukeller, a beer hall, in Munich, nationalist paramilitary groups surrounded the scene and held the triumvirate hostage. The triumvirate soon announced that it would join ranks with the paramilitary—bringing its command over the Bavarian military and police with them—and cooperate enthusiastically under Hitler.

Kahr, who up to that moment had allied with far-right factions, unexpectedly became a lynchpin in the response that crushed the putsch.

Gessler responded to the putsch by transferring his authority to General Hans von Seeckt, with instructions to “do whatever you must to secure the republic.” Seeckt, a right-wing military leader and Monarchist who knew more than most of the devastating impact of the Treaty of Versailles, is credited with having resuscitated the German army in the 1920s. His commitment to Germany and its people was clear, but so was his disdain for the politicians in Berlin.

During a previous putsch, Seeckt had refused to mobilize the military against the putschists, and the government was forced to evacuate Berlin. While eventually he ordered the German military to bring an end to the uprising, it was not because he supported the sitting government, but because he was compelled to do what was best for his country. He may have admired Hitler, but he proved loyal to constitutional stability and the rule of law.

While initially appearing to yield to the coercion of Hitler and his entourage, Kahr's steadfast dedication to law and order would not permit him to collaborate in the overthrow of Germany’s constitutional framework. In the days leading up to his speech at the beer hall, Kahr and the triumvirate had already secretly arranged for a peaceful conclusion to the tension between Munich and Berlin.

By the time the putsch began, it had already failed. During the night, Hitler left the beer hall to take care of some business, leaving Ludendorff in charge. This moment is often regarded as Hitler’s fatal error, as Ludendorff, having been convinced by Kahr that the triumvirate had fallen in line as willing conspirators, allowed them to leave the premises.

Once safe, Kahr ordered local radio stations to broadcast a clear message: “Generalkommissar von Kahr, Colonel von Seisser, and General von Lossow renounce the Hitler putsch. Expressions of support extracted at gunpoint are invalid.” He followed this statement by issuing a series of declarations that outlawed and dissolved the Nazi Party, prohibited local newspapers from printing for the day, and ordered the arrests of Hitler and Ludendorff.

Kahr’s actions to protect the Weimar Republic exemplified the will among even the most discontented sections of the establishment to preserve the existing order, even when that order was severely challenged at the height of its vulnerability. The failure of the Beer Hall Putsch was not just a personal defeat or misstep for Hitler; it was a triumph for the Weimar Republic, illustrating its unexpected staying power.

Despite the overwhelming odds stacked against it—economic collapse, political instability, and social unrest—the Weimar Republic did not just limp on. It weathered one of the most daring challenges to its existence and emerged, perhaps paradoxically, stronger. By the time Hitler and his conspirators faced trial the following spring, the currency had stabilized and the German republic remained.

From his putsch attempt, Hitler learned that if he wanted to attain power in Germany, he would have to do it democratically.

![]()

Learn More:

Koepp, Roy G. "Gustav von Kahr and the Radical Right In Bavaria." Historian, 77 (2015): 740-763.

Hett, Benjamin C. Death of Democracy: Hitler’s Rise to Power and the Downfall of the Weimar Republic. New York: Henry Holt and Co, 2018.

Evans, Richard J. The Coming of the Third Reich. New York: Penguin Books, 2003.