Secretary of State John Kerry meeting in Lausanne with Iranian Foreign Minister Zarif, 2015.

Preventing Iran from developing nuclear weapons has been a foreign policy imperative for years, not just for the United States but for Israel and Western Europe as well. That imperative, as historian Annie Tracy Samuel tells us, fails to take Iran's own recent history into account, especially during the Iran-Iraq War. This month she invites us to look at this nuclear dilemma from Tehran's point of view.

Over the course of the past year international negotiators have met periodically in Vienna in an attempt to accomplish what was long considered a near-impossible task. Once again they are working to conclude an agreement with the Islamic Republic of Iran to check its nuclear activities, ensure that it doesn’t develop nuclear weapons, and thereby mitigate one of the most pressing international security concerns of the past several decades.

In 2015, the weight of historically tense U.S.-Iranian relations was overcome and the nearly impossible realized in the form of the nuclear deal known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA).

But that monumental diplomatic achievement fell victim to the regressive and reactionary foreign policies of the Trump presidency. With a confidence born of disdainful egoism and contempt for the past, the former president destroyed that highly successful accord and with it the improvements in relations between the United States and Iran that had accompanied it.

Moreover, in withdrawing the United States from the JCPOA and instituting a policy of “maximum pressure” designed to bring “Iran to heel,” Trump reversed the progress made by his predecessor to overcome Iran’s well-founded distrust of the United States and set efforts to curb its nuclear program back to square one.

Trump also reinforced Tehran’s fears about the dangers of engaging with Washington. In acceding to the original accord, the Iranian leaders who negotiated it had staked their names and political careers on the claim that the United States could be trusted, that lowering Iran’s defenses would not make it vulnerable, and that the country would benefit from engaging with its long-standing adversary.

And for a time, it seemed they were right; that is, until Trump proved them wrong. Those in Iran who had criticized the deal—who maintained that the United States had proven itself untrustworthy, that Iran must not jeopardize its independence and security by compromising with a country committed to restricting its power, and that the past was too fraught to be overcome—were vindicated.

To be sure, the breakdown of previous negotiations and resolutions derives from a variety of factors and failings on both sides. At the same time, Iran’s continuous defiance of past predictions and contemporary assessments of its aims, strategy, power, and nuclear program always stems in part from a profound lack of strategic empathy that the careful consideration of history provides.

The Legacies of the Past

With the exception of the policies that culminated in the JCPOA, the conventional wisdom on Iran in the United States has rested precariously on several deficiencies and misinterpretations.

First and foremost, the established approach suffers from a neglect of the basic scheme of modern Iranian history. It disregards especially the enormous role of outside powers in curbing Iran’s independence and sovereignty, pilfering its resources and wealth, and manipulating its internal politics for their own benefit, often by propping up autocratic and unpopular but pliable rulers.

Second, the standard narrative holds that Islamic revolutionary ideology has been the paramount frame of reference guiding Iranian policymakers since the establishment of the Islamic Republic in 1979, and thus forms the lens through which the regime’s nuclear program and policies ought to be viewed.

Third, existing interpretations cast Iranian policies as fundamentally aggressive and expansionist, having as their foremost aims the establishment of an Islamic and revolutionary regional order, Iranian hegemony, and the obliteration of Israel. This view accordingly deems Iran a serious threat to international security even without a nuclear weapon and a potentially existential threat should it acquire one.

All these contentions are detrimental to understanding Iran and preventing it from acquiring nuclear weapons.

In the first case, Americans know little about their country’s relationship with Iran in the present, and even less about its bases in the past. Iranians, however, regard the relationship as part of a long and troubling pattern of foreign intervention that reaches back into the nineteenth century.

A profound consciousness of the past informs Iran’s conception of itself and its position in the world. Current attempts to reset the fraught relationship must therefore be informed by history and by an understanding of how Iran perceives the history of its relations with the United States.

Indeed, Iranian leaders argue that if interactions between Iran and the United States are to improve, these legacies will have to be acknowledged and rectified. That contention, further, is one shared by Iranian leaders from across the political spectrum, which is particularly notable given the deep cleavages that divide Iran’s leaders and people alike and that very few policies can effectively bridge.

There are several significant historical episodes of the United States working counter to the interests and wellbeing of the Iranian people that still resonate in Iran. These include orchestrating (along with the United Kingdom) the overthrow of popularly elected prime minister Mohammad Mosaddeq and subsequently supporting the repressive regime of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, who was overthrown in the 1979 Iranian Revolution.

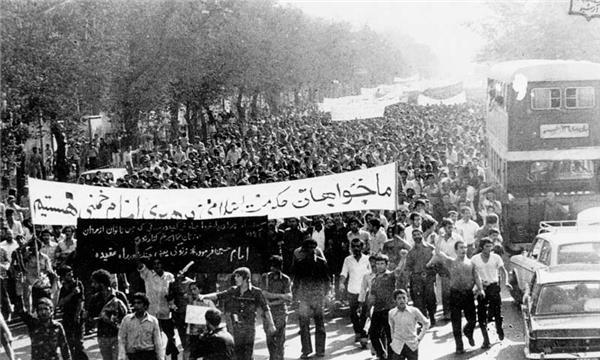

The episode with the greatest bearing on the nuclear negotiations, however, is U.S. involvement in the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq War. Beginning just eighteen months after the revolution, lasting nearly eight brutal years, and ending less than four decades ago, the depth, extent, and endurance of the conflict’s impact are difficult to overstate.

U.S. support for Iraq in that war has profoundly shaped Iranians’ views and distrust of the United States in the years since.

According to figures as dissimilar as Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, former Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif, and military commander Masoud Jazayeri, U.S. policies like providing aid to Saddam Hussein and failing to condemn his use of chemical weapons means that the United States, in the words of Jazayeri, is “complicit in all of the devastation and crimes that occurred during that period.” Accordingly, “before America considers its future relations with the Islamic Republic of Iran,” Jazayeri warned in 2013, “it must clear the many debts it has to the Iranian nation.”

Zarif, Khamenei, and others have made nearly identical arguments, with the former foreign minister pointing to those same policies to assert that the “historical sources of Iran’s very serious and deep mistrust of the behavior of the United States needs to be addressed” for trust to be restored and for relations and negotiations over its nuclear program to progress positively.

Implacably Ideological?

Second, ever since the 1979 revolution succeeded in toppling the shah’s U.S.-backed regime, fears that Iran presented a wildly dangerous and irrational threat, driven by its “fanatical,” Islamic, and revolutionary ideology, have dominated U.S. thinking about Iran. This interpretive tone is widely apparent in media, scholarship, and policy alike, and has been a stubbornly consistent feature of the narrative in the United States, even if it has become more measured over the years.

A December 1980 article in The New York Times, for example, claimed that “the dominant clerical political figures” who had come to power in Iran espoused an “ideology hold[ing] that Islam should sweep across all borders” and that the war they were then fighting with Iraq must be understood in those terms as well.

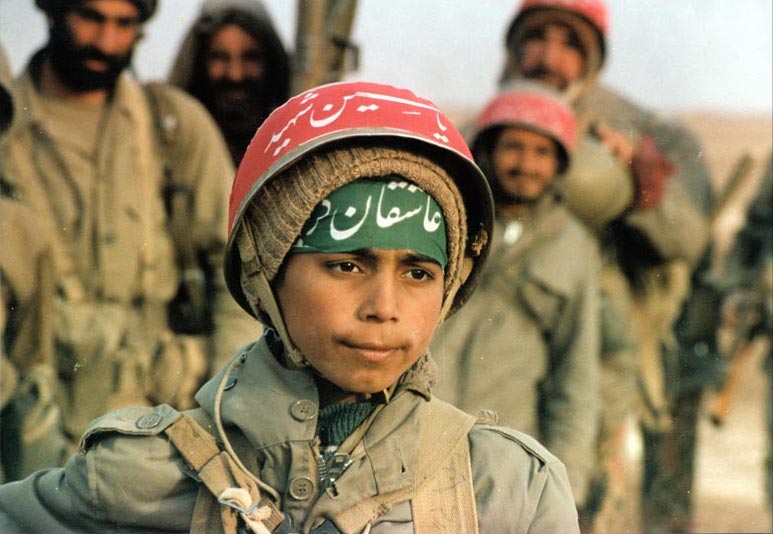

Another article from the same period and publication turned Americans’ gaze to “a lean, fiery-eyed, young mullah”—a favorite term used by Western writers to refer to Shi’i clerics but one that often carries derogatory connotations in Iran—who was effectively inspiring Iranian soldiers fighting in the war. Those soldiers, the article asserted, were fighting not to free their country from a foreign invasion, but for “martyrdom,” which was evident from the fact that they “universally … describe their motivation in theological terms.”

Yet despite their eccentricity, Iran’s “zealous” and “fiercely religious” fighters proved formidable foes for the Iraqi invaders and enigmatic subjects for Western reporters as they “charged headlong against tanks in search of martyrdom” and in the process effectively “blunted” and then reversed the Iraqi invasion.

And therein lies the rub. The Islamic Republic, the standard narrative holds, is not just fanatical but powerful, not just irrational but dangerous and threatening to the forces of the Western-dominated liberal international order and the friendly autocrats who maintain it in the Middle East and elsewhere. Just imagine, such sophistry entreats, what this mullah-led regime might do with a nuclear bomb.

The Shadow of the Iran-Iraq War

Despite the American focus on ideology and its purported role in driving Iranian behavior, by far the most important experience influencing Iran’s security strategy generally and its nuclear program specifically is not the Islamic Revolution but the Iran-Iraq War. More than anything, that war generated Iran’s determination to prevent an armed conflict that could directly threaten its security and territory.

Indeed, the defining features of this war (at least from Iran’s perspective)—an all-out attack on its territory, its almost complete lack of allies, its inability to fulfill its weapons and other matériel needs, and its ability to mobilize its population to prosecute the war—have since become the key considerations shaping Iran’s security policy.

They have been manifested as the determination to prevent such an attack from happening again, particularly through robust conventional deterrence; concerted efforts to form regional alliances and to minimize enmity against Iran; the development of indigenous defense industries and capabilities, enabling Iran to be as self-reliant as possible; and strategies for maintaining popular support for the regime, at least to the extent that such support will prove sufficient to mobilize people to fight in Iran’s defense.

The Iran-Iraq War also led Iran to appreciate how indigenous nuclear technology and weapons of mass destruction (WMD) can contribute to a self-sufficient security architecture.

Iraq’s deployment of chemical weapons during the conflict left Iran with distinct and contradictory conclusions. On one hand, Iranians intimately understand the heinousness of WMD and thus maintain a lasting abhorrence of their use. On the other hand, they regard Iraq’s employment of chemical weapons as having been very effective because it gave Iraq an important advantage on the battlefield, deterred Iran from launching attacks, and contributed to Tehran’s decision to end the war.

Iran’s experience with WMD thus helps explain the country’s vacillation regarding the acquisition of both chemical and nuclear weapons. While Iran’s understanding of the deterrent and practical utility of these weapons had led it to pursue their possession, its repugnance toward them helped undermine these efforts.

Although it is not possible to determine the extent to which the latter has deterred Iran from proliferating, Iranian leaders have asserted that the country’s exposure to chemical weapons during the Iran-Iraq War has contributed to its reluctance to develop an unconventional arsenal.

In addition to Iran’s experience as the victim of chemical weapons during the war with Iraq, the fact that world powers failed to condemn Iraq’s actions in invading and using WMD against Iran has had direct bearing on Iran’s nuclear policy.

To Iranian leaders, the selective toleration and inconsistent condemnation of the development and use of WMD exemplifies the inequitable structure of the international system generally, and the nonproliferation regime specifically, in which countries like Iran have usually been disadvantaged while countries like Israel maintain an actual arsenal of nuclear weapons without any of the retributive response Iran’s own activities have generated.

Iranian leaders are quite cognizant of this duality and have sought to remedy their vulnerability by maintaining the ability to independently defend their national and security interests. Doing otherwise, they assert, would be foolish.

For example, according to a report published about a week after his assassination by the United States in January 2020, former Quds Force commander Qassem Soleimani issued such a warning to his compatriots in the final month of the Iran-Iraq War. Appearing under the headline “The Superpowers’ Friendship with Us Is Like the Friendship of a Wolf and a Sheep,” the story recounted that Soleimani had demonstrated the imprudence of trusting a superpower by comparing it to having “a friend who swallows us whenever he gets hungry.”

Indeed, independence, self-reliance, and self-sufficiency have long formed the core of the country’s international posture. Though more prominent under the Islamic Republic, those tenets were also manifest in the shah’s foreign and nuclear policies, and their durability again reflects Iran’s long history of struggling to overcome its forced subservience to foreign powers.

Self-Protection and Aggressive Defense

Finally, the common view of Iran as belligerent and bellicose is likewise undermined by a sober assessment of Iranian sources and actions. The West’s belief that the Islamic Republic pursues aggressive policies that threaten Iran’s neighbors and international security has had an immense impact on U.S. policy. While much of Tehran’s rhetoric and some of its actions are aggressive in tone and practice, they have consistently been driven by self-protection and deterrence.

Today, Iranian leaders often directly connect their “aggressive defensive” policies to their experiences in the Iran-Iraq War, and especially to their failure to protect themselves from the Iraqi invasion that initiated it. In their view, the aggression against Iran that the war embodied has continued in the form of the pressure and sanctions imposed on the country as a result of its nuclear activities, which have exacted a severe toll on its people.

In the years since the war, Iranian leaders have developed a security strategy that aims to rectify the weaknesses exposed by the conflict. The impetus to do so has been heightened by Iran’s position in a perennially volatile region, surrounded by U.S.-backed adversaries stocked with advanced weapons, and its belief that the United States’ ultimate objective is to weaken and isolate the country if not change its regime. Many of the Islamic Republic’s foreign activities—like its support for nonstate actors and its involvement in regional conflicts—have been driven by self-protection rather than offensive aggression.

Thus, Iranian policies, whether aligned with U.S. interests and values or not, should not be dismissed as irrational or branded as fundamentally expansionist. This is not to say that U.S. concerns surrounding Iran’s activities are ill-founded. Tehran’s policies in certain areas (e.g., the Syrian civil war) are patently deleterious and destructive and should be countered. Yet the fact remains that their primary aim is not truculence or regional hegemony but the country’s survival.

Iran’s Nuclear Program

It is in this context that we must understand Iran’s long-held stance of refusing to acquiesce to demands for it to halt its nuclear program entirely, which derives from the lessons of history and is based on the conviction that doing so would erode its independence and security. From the initiation of its nuclear program in 1967 to the present, the shifts in Iran’s nuclear policies have reflected the fluctuating set of threats it faces and an evolving set of measures designed to promote its security in the given circumstances.

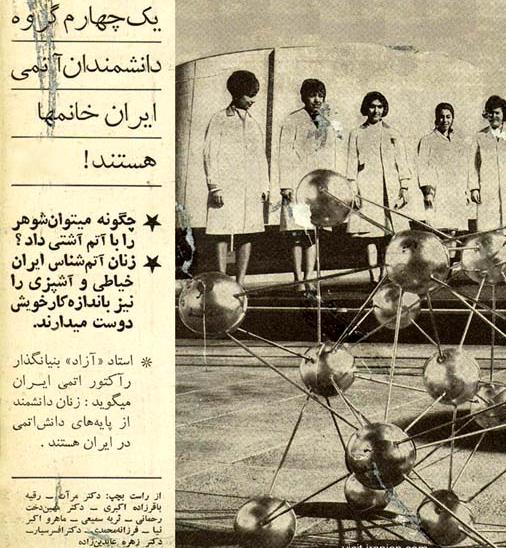

Although launched in 1957 as part of the Atoms for Peace initiative spearheaded by U.S. President Eisenhower, Iranian leaders consistently declined to commit to limiting their nuclear program to purely peaceful purposes. Thus, Iran’s policy of hedging—of developing a nuclear energy infrastructure that could also serve as the basis for a weapons program—was first espoused not by the Islamic Republic but by the monarchy.

The shah’s regime did not decide to weaponize the program in part because its conventional superiority and alliance with the United States helped guarantee its security and made doing so unnecessary. But the shah nonetheless held fast to preserving that possibility. While in the mid 1970s he expressed concern about the dangers of nuclear proliferation, he maintained that the fact of it meant that Iran would be foolish to rule out weaponization altogether.

It was the Islamic Republic, in fact, that proved willing to abandon not only that possibility but the entirety of its nuclear program. Faced with the program’s soaring costs and dependence on foreign advisors, and in light of revolutionary leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s avowed and religiously based opposition to nuclear weapons, the new regime decided to scrap it in the spring of 1979, just a few months after coming to power.

If anything, then, Islam has constrained, not emboldened, Iran’s nuclear ambitions.

Further, the Islamic Republic reversed course not because of the impetus of ideology but as a result of the exigencies of insecurity generated by the Iran-Iraq War. Confronted at that point with a foreign invasion launched by a state with a covert nuclear program and a proven willingness to deploy WMD, Iranian leaders determined in the mid 1980s that the security of their country demanded the revival of the nuclear program and the development of the technical know-how and capability to weaponize it if necessary.

Yet, in the early 2000s, when it became clear that its nuclear policies were making Iran less rather than more secure—with crippling sanctions imposed on the country and the looming threat of another war—Tehran came to the negotiating table prepared to discuss halting some of its nuclear activities. Thus, the conception that a nuclear weapon would decrease rather than increase the country’s security and defense has forestalled weaponization and strengthened Iran’s willingness to make the kinds of compromises it committed to as part of the JCPOA.

This commitment to flexibility and pragmatism is indeed a defining feature of Iranian policy- and decision-making, though one that is too often discounted in Western analyses. It’s also one that even leaders typically characterized as “hardline” or “dogmatic” opponents of engagement with the United States have espoused. For example, in the midst of the negotiations culminating in the 2015 nuclear deal, commanders of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps left room for the possibility of rapprochement should the United States alter its policy of enmity toward the Islamic Republic and should some trust between the countries be restored.

It was the discounting of this record of pragmatic decision-making and the willful neglect of the historical bases of Iran’s distrust of the United States, its sense of insecurity, and its quest for independence that generated the unnecessary revival of the nuclear standoff in 2018 and the efforts over the past year to resolve it once more.

Yet, as the successful conclusion and implementation of the JCPOA demonstrated and as Iranian leaders have reiterated, a negotiated end to that standoff and peaceful means for countering the weaponization of Iran’s nuclear program are indeed possible.

Making them a reality depends on reinvigorating and sustaining an approach to Iran that takes history into account.

Ervand Abrahamian, Oil Crisis in Iran: From Nationalism to Coup D’état (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2021).

James G. Blight, et. al., Becoming Enemies: U.S.-Iran Relations and the Iran-Iraq War, 1979-1988 (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2012).

Malcolm Byrne and Kian Byrne, Worlds Apart: A Documentary History of US-Iranian Relations, 1978-2018 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2022).

John Ghazvinian, American and Iran: A History, 1720 to the Present (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2021).

Bryan R. Gibson, Covert Relationship: American Foreign Policy, Intelligence, and the Iran-Iraq War, 1980-1988 (New York: Praeger, 2010).

John W. Limbert, Negotiating with Iran: Wrestling the Ghosts of History (Washington: United States Institute of Peace, 2009).

Trita Parsi, Losing an Enemy: Obama, Iran, and the Triumph of Diplomacy (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017).

Lawrence G. Potter and Gary Sick, eds., Iran, Iraq, and the Legacies of War (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004).

Ariane M. Tabatabai, No Conquest, No Defeat: Iran’s National Security Strategy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

Annie Tracy Samuel, The Unfinished History of the Iran-Iraq War: Faith, Firepower, and Iran’s Revolutionary Guards (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2022).