The 1972 Munich Olympics were billed as Die Heiteren Spiele—the “Happy Games.” West Germans hoped they would help rehabilitate their country in international eyes after the horrors of Nazism, and nothing symbolized this new Germany more than the participation of a team from Israel. To avoid appearing militarized, the Olympic safety guards were largely unarmed.

The “Happy Games” soon became the “Olympics of Terror.” A global audience watched a tragic attack on the Israeli athletes unfold on television, which brought the world’s attention to the plight of Palestinians even as it drew condemnation for the Palestinian terrorists’ methods.

On September 4, while the Israeli team settled into bed in their apartments at 31 Connollystrasse in the Olympic Village, a group of Palestinians met to plan Operation “Ikrit and Biram” under mission commander “Issa,” Arabic for Jesus. Ikrit and Biram were two Palestinian Christian villages that had been razed by the Israeli Defense Force in 1951.

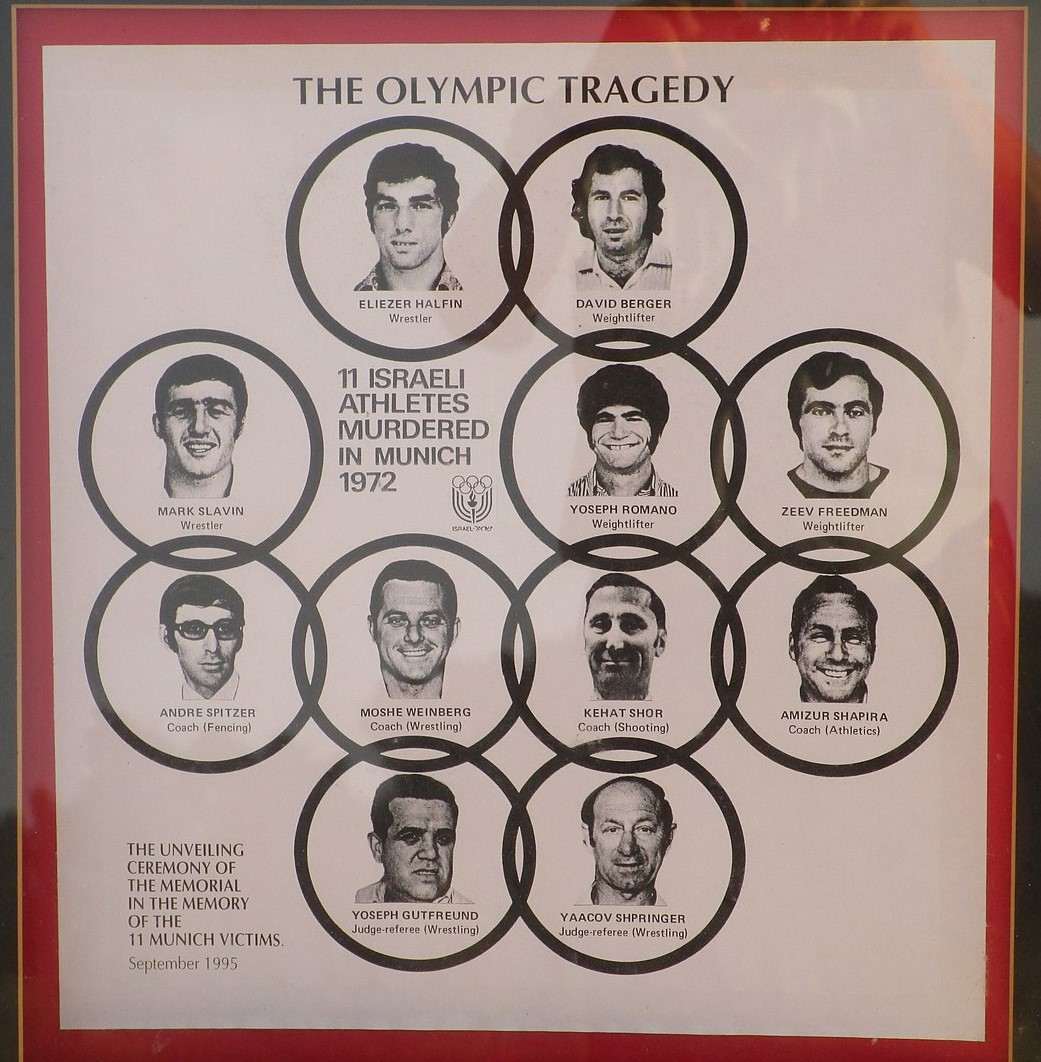

At 4:10 am, drunk American athletes helped the tracksuit-clad fedayeen over the Village fence. Despite Israeli wrestling judge Yossef Gutfreund’s efforts to block the way, the terrorists pushed into 31 Connollystrasse. Tuvia Sokolsky, a Holocaust survivor, escaped out the back window, but 11 other teammates, most in their underwear, were bound at their wrists and ankles.

The hostages attempted to fight back. Yossef Romano and Moshe Weinberg were shot trying to grab the terrorists’ guns; Gad Tsobari was able to sprint away in the distraction. Reports revealed that the terrorists gruesomely castrated Romano, likely before his death. Nine hostages remained.

As the Olympic Village woke, officials locked the gates and isolated the dorms. At 7:40 am, two sheets of paper floated down from a window detailing the terrorists’ demand: the release of prisoners—234 from Israel and two from West Germany—by 9 am, or an Israeli hostage would be executed every hour. The prisoners were to be taken to an Arab country for the exchange. The demands were signed Black September.

The post-war UN partition plan of Palestine envisioned both an Arab and a Jewish state, but after the 1948 Arab-Israeli War only Israel existed, with most Palestinians displaced as refugees. In the 1967 war, a threatened Israel unilaterally annexed huge swaths of the surrounding territory. Palestinians refer to the events of 1948 and their dispossession and statelessness as al-Nakba—“catastrophe.” The Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) was born in 1964 with the goal of self-determination for Palestine.

In 1970, Jordan’s King Hussein ruled more Palestinian refugees than Jordanians, and he feared overthrow from the defiant PLO. His army killed thousands of Palestinians in what was called “Black September,” and many survivors fled. A secretly affiliated extremist wing of the PLO named Black September was formed the next year to avenge the slaughter.

The secretive organization assassinated Jordanian Prime Minister Wasfi Al-Tell. The Israeli Olympic team was their newest target.

As German officers tried to negotiate, Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir told West German officials she refused to bargain with terrorists and trusted West Germany would do their best to protect the hostages. Back in Munich, Issa, who always held a hand grenade, extended the deadline several times.

Botched rescue attempts included sending police dressed as chefs to deliver food for the hostages in the hope they would be let in; but Issa carried the boxes in one by one. “Operation Sunshine” sent police officers onto nearby rooftops to ambush 31 Connollystrasse, but as the world watched the roofs on live TV, so did the terrorists inside their apartment. Issa shouted at the officials to abort the mission.

As West Germany stalled, Issa grew impatient, eventually threatening to kill all the athletes. An agreement was reached: the terrorists and hostages would be helicoptered to Fürstenfeldbruck military airfield, where a fully equipped Boeing 727 would be waiting, Issa was promised, to take them to Cairo.

At 10:36 pm, the eight terrorists and nine hostages arrived at the airport. Issa and second-in-command “Tony” hurried to inspect the Boeing but encountered an empty plane.

Twenty minutes earlier, 13 German police officers dressed as flight crew for a planned ambush had abandoned mission over “fear for their lives.” The disguised squad was inexplicably left to wear police trousers, and the plane, which would never take off, was carrying 8,300 liters of fuel. Even a single bullet could engulf the whole scene in fire.

As Issa and Tony returned from the deserted plane, two of five police sharpshooters opened fire from a rooftop. The scene quickly devolved into chaotic crossfire as the lighting units were hit and the airfield plunged into total darkness. A tense silence followed the frenzy.

At nearly midnight, German police vehicles rolled in. The terrorists, who still had hostages, panicked. One Palestinian threw a grenade into his fueled helicopter, killing four hostages in a fireball; the remaining five in the other helicopter were shot, still shackled. Three terrorists were captured.

The German rescue attempt was a tragic, colossal failure. At 3:17 am, Reuters declared, “Flash! All Israeli hostages seized by Arab Guerrillas killed,” in addition to five terrorists and one German police officer. A memorial held the next day honored the victims, but the Games continued.

Effects of the hostage crisis reverberated. The massacre was met with international horror. Global news coverage of the violent attack shocked the world, affecting public opinion on non-state violence as a political tool.

Germans failed in their efforts to rehabilitate their global reputation and were seen as unprepared and incompetent. They, in turn, blamed the Israeli government for not yielding to the terrorists’ demands. Only 50 years later, on September 5, 2022, did the German government formally apologize to the families of the victims for failing to keep the Olympic athletes safe.

Some Palestinians saw the terrorist attack as bringing welcome, worldwide attention to their struggle, despite denunciations for the terrorists’ methods. A PLO organ wrote, “It was like painting the name ‘Palestine’ on a mountaintop visible from all corners of the globe.”

For Israelis, the public killing of Jews on German soil reopened old wounds and sparked a movement for retribution. The emotional response to the tragedy led to the creation of an Israeli assassination campaign, known as Operation “Wrath of God.”

![]()

Learn More:

Klein, A. J. (2005). Striking back: The 1972 Munich Olympics massacre and Israel's deadly response. Random House.

Reeve, S. (2000). One Day in September: The full story of the 1972 Munich Olympics massacre and the Israeli revenge operation 'Wrath of God' with a new epilogue. Arcade.

Armed Struggle and the Search for State: The Palestinian National Movement, 1949-1993– Book by Yezid Sayigh

Bergman, R. (2018). Rise and kill first: The secret history of Israel's targeted assassinations. Random House.

ARTICLES

Wolf, J. B. (1973). Black September: militant palestinianism. Current History, 64(377), 5-8, 37.

Bohr, F. (2012, August). Germany's Secret Contacts to Palestinian Terrorists. Der Spiegel. https://www.spiegel.de/international/world/germany-maintained-contacts-with-palestinians-after-munich-massacre-a-852322.html

50 Years After Attack at Munich Olympics, a Formal German Apology (New York Times). https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/05/world/europe/germany-israel-apology-munich-games.html

TV & PODCASTS

Crisman, S. (Director). (2016, July 6). Munich '72 and beyond [TV special]. KLRU Presents. https://www.pbs.org/video/klru-presents-munich-72-and-beyond/

“One Day in September” documentary directed by Kevin McDonald.

BBC Radio’s episode of “You Don’t Have to Be Jewish” from Sep 17, 1972 https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p09fwlwn