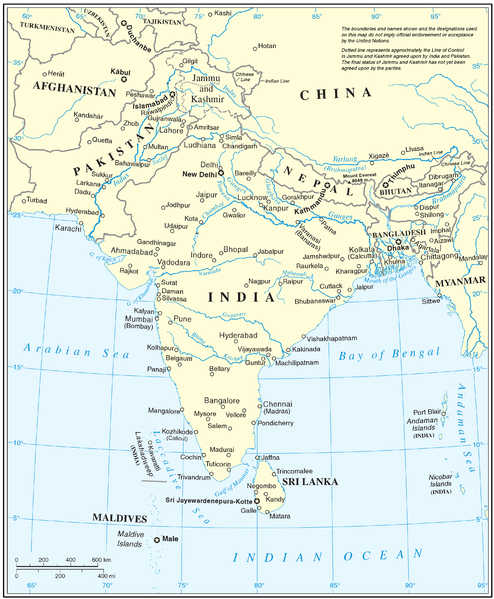

Salman Rushdie’s novel Midnight’s Children features a memorable adventure through the jungles of the Sundarbans, in whose labyrinths of mangroves the book’s main character Saleem rediscovers forgotten memories of his past, of India’s early years of independence, and the upheavals wrought by Partition. It is fitting, therefore, that John Keay’s book, Midnight’s Descendants, begins in these same mangroves, where the maze of waterways serves as a metaphor for the subcontinent’s complicated post-colonial coming of age. Favoring academic history over Rushdie’s magical realism, Keay’s work examines the history of South Asia from the Partition of British India in 1947 to the present. For Keay, the tumultuous histories of independent India, Pakistan, and later Bangladesh stem directly from Partition, which was hasty, chaotic, and left many problems unresolved.

After decades of discussion over the fate of British India, the plan for independence and Partition was announced only ten weeks in advance and featured many unresolved issues, including the fate of the princely states and identification of exact borders. In finally quitting India, the British favored expediency over exactitude and forethought. The result was the unchecked migration of between ten and twenty million people, accompanied by a quick descent into chaos, violence, and at times, mass slaughter. Thus, in addition to the usual business of state formation and administration, both India and Pakistan were confronted with millions of often destitute and traumatized refugees at the moment of independence, swelling urban centers such as Delhi, Calcutta, and Karachi far beyond their capacity.

Keay points out that India enjoyed certain immediate advantages over Pakistan, including geographic contiguity and the inheritance of a functioning state apparatus left from the British. Both India and Pakistan initially embraced the rhetoric of secularism, but for the latter this proved increasingly problematic. Ethnic and linguistic divisions in Pakistan meant that an Islamic religious majority was the only real justification for the nation’s existence and the inclusion of East and West Pakistan in the state. Internally, East Pakistanis felt increasingly underprivileged, neglected, and politically excluded. These tensions exploded in the early 1970’s as Pakistani troops massacred an estimated three million Muslim East Pakistani “insurgents” and then targeted the ten million strong Hindu minority, who were blamed for stoking rebellion and undermining Muslim solidarity. This created a refugee crisis on India’s eastern border that brought the two nations to war in 1971, which ended in a swift, decisive Indian victory and secured the secession of East Pakistan as the independent country of Bangladesh.

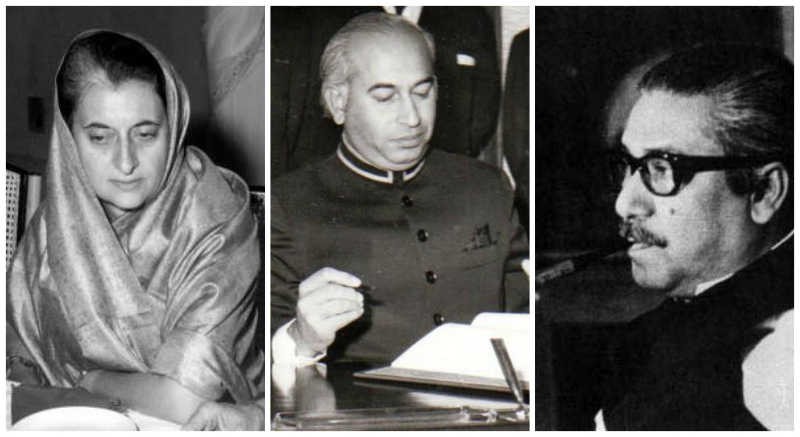

In Keay’s estimation, the 1970’s ushered in a new period of populist rule under India’s Indira Gandhi, Pakistan’s Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, and Bangladesh’s Mujibur Rahman. All three leaders came to power as representatives of directly elected civilian governments, though eventually all three would exhibit dictatorial streaks. They would also all pay for their political actions with their lives: Mujibur Rahman and most of his family were assassinated during a military coup; Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was also executed following a military coup; and Indira Gandhi was shot and killed by her Sikh bodyguards.

In order, India’s Indira Gandhi, Pakistan’s Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, and Bangladesh’s Mujibur Rahman

In order, India’s Indira Gandhi, Pakistan’s Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, and Bangladesh’s Mujibur Rahman

During the 1980s, Pakistan and Bangladesh experienced extended periods of military rule under leaders committed to promoting Islamic identity. The Soviet war in Afghanistan and the influx of ideas and money from the Gulf States supported the proliferation of extremist religious ideologies in Pakistan. In Bangladesh, military rule was replaced with an ongoing cycle of competing dynastic politics as two leaders, General Ziaur Rahman’s widow Khaleda Zia, and Mujibir Rahman’s daughter Sheikh Hasina Wajed, prioritized their obsessions with seeking justice for past wrongs over the present needs of their country. In India, the rise of a new wave of Hindu nationalist movements threatened the subcontinent’s secular identity. These movements promoted Hindu-centric versions of history and have turned violent, as when protestors demolished the sixteenth-century Babri Mosque brick-by-brick in 1992.

Despite the bleak portrait of modern South Asian history presented throughout the book, Keay closes his study on a hopeful note by focusing on the increasing economic prosperity the era of globalization has brought to India—though his earlier point that, in terms of numbers, there are more poverty-stricken people in India than in Pakistan and Bangladesh combined somewhat tempers this optimism.

This is a complex story, and Keay has covered a great deal of ground. The end product suffers greatly, however, from a lack of focus and falls victim to its own ambitions. By beginning the story in 1946, Keay divorces Partition from the larger historical context. The motivations of key figures such as Nehru and Jinnah are obscured as a result, while the British are largely exonerated as arbiters merely attempting to find a workable solution. Additionally, though organized chronologically, the juggling of multiple narratives makes the timeline muddled and difficult to follow regardless of the reader’s familiarity with the period. The half-hearted inclusion of Sri Lanka and Nepal—while understandable in a history of “South Asia”—feels haphazard and distracting. Lastly, Keay does not commit to the kind of story he wants to tell and wavers between social, economic, and political history, compounding the confusion arising from the various individual narratives already at play. This is especially problematic as the book appears to be directed at a popular audience rather than an academic one (after all, Keay is a journalist, not a historian). There is much to learn in Midnight’s Descendant’s, but the multiple stories are not told in an accessible or compelling way.