In her debut book, Daphna Oren-Magidor presents a broad overview of the experience of infertility in England between 1540 and the first half of 18th century. She argues that most historians of this period underestimate both the emotional toll on and social ramifications for childless married couples in Early Modern England. To elucidate this point, Infertility in Early Modern England explores the ways in which religion, medicine and gender interacted to define the experiences of childlessness for both men and women and holds that the presence of widespread negative attitudes surrounding infertility reflected contemporary fears of an upended social order.

The book is organized into four thematic chapters. In the first chapter, “Experiencing Infertility,” Oren-Magidor uses the letters and diaries of aristocratic men and women to explore how each interpreted infertility differently. She argues that “regardless of how men were affected by infertility, it was not as central to their identity and the fulfillment of their social and religious duties as it was for women” (33).

Instead, Oren-Magidor finds that men were more concerned with questions of inheritance and legacy. Women, on the other hand, struggled to comes to terms with their infertility in large part because they also understood childbearing as a religious duty which they had failed to fulfill (39). While she convincingly establishes that there were different social meanings for infertility between men and women, I am not entirely persuaded that infertility was less important to men’s identities than it was to women’s. The significance of an heir for purposes of inheritance might have been as just as important to shaping men’s identity as the religious implications were for women’s.

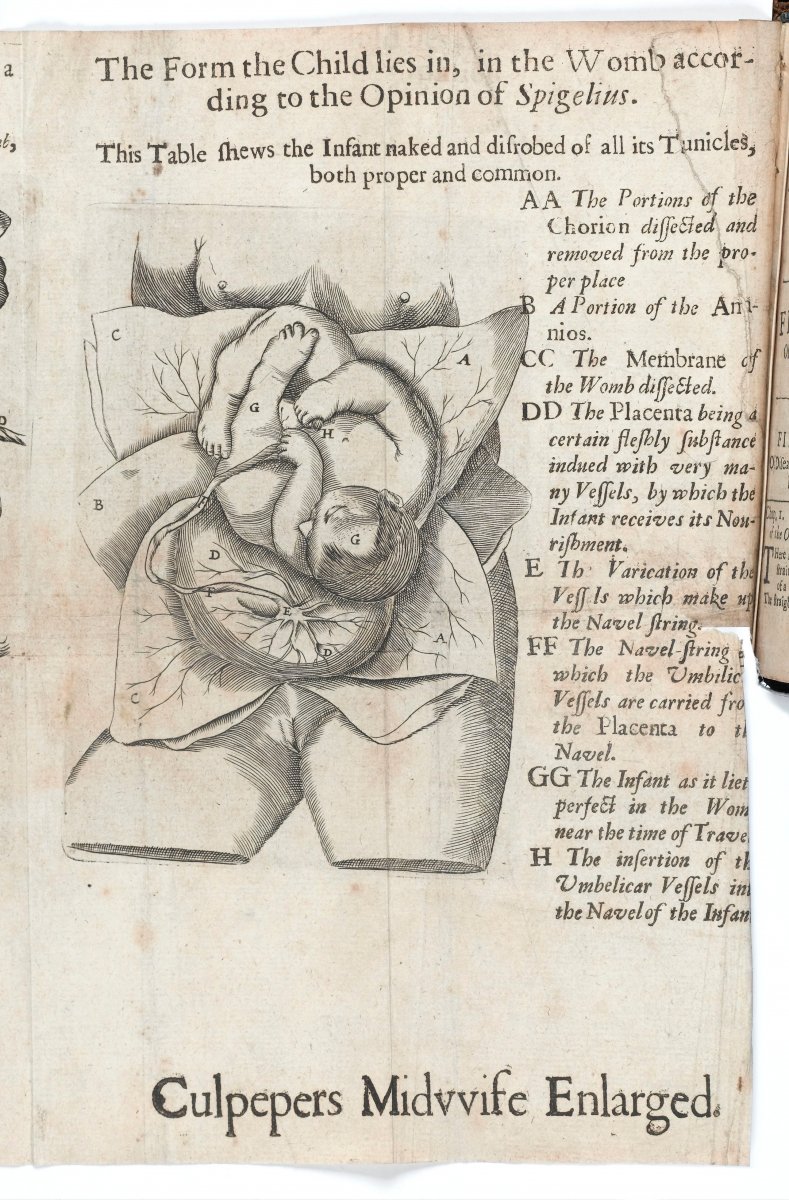

In “Explaining Infertility” Oren-Magidor emphasizes the ways in which religious beliefs and medical theories worked together to explain the occurrence of infertility. For example, she points out that many of the behavioral causes of infertility addressed in the medical literature correlated to ‘mortal sins’ like lust and gluttony. In one illuminating example Oren-Magidor offers, Nicholas Fontanus, the author of a 17th century gynecological manual, linked women’s lust with infertility, suggesting that “an excess of sexual activity” would hinder conception. His views were not uncommon, either. Nicholas Culpeper in his 1651 A Directory for Midwives suggested that prostitutes were unlikely to conceive for the very same reason. Unfortunately, much of this chapter loses the religious through-line and instead relies on the reader to make connections between the many causes of infertility as they were presented in medical manuals and religious beliefs.

Similarly, in the following chapter titled ‘Society and Infertility,’ Oren-Magidor saves the most succinct statement of argument until the final few sentences in which she claims that when couples failed to produce children they also upset the social order by allowing for “an opening for the reversal of anxieties about paternity” (112). For example, men who were impotent were sometimes mocked as effeminate and publicly ridiculed (99) and infertile women were occasionally described as more masculine, depicted as too outspoken or visible in public spaces. Specifically, Oren-Magidor describes tropes about the adulterous barren wife who was cured of her infertility when transgressing the marital bed (105-110).

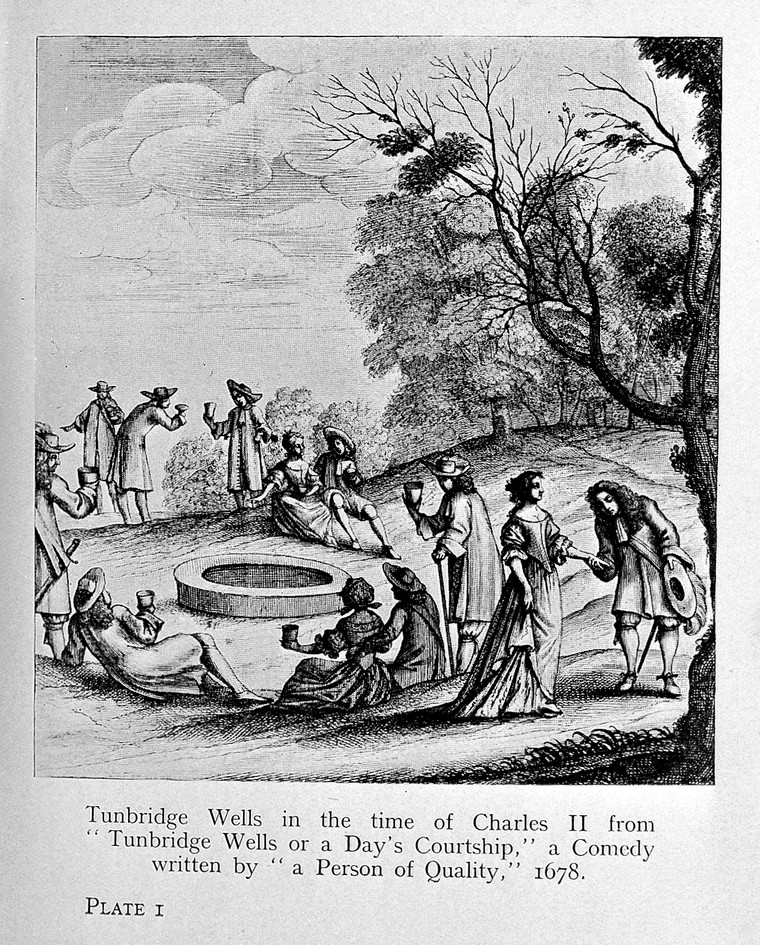

Finally, “Treating Fertility Problems” suggests ways in which women employed both religious beliefs and early modern ‘physic’ to cure infertility. While some of the conclusions in this chapter mirror those found in the first (and could have probably been integrated there), the section describing “taking the waters” is especially fascinating. Oren-Magidor traces the changing cultural meanings in the use of baths to treat infertility in early modern England.

She begins by noting that in pre-Reformation England, the baths held religious meaning and those who ‘took the waters’ could pray for intercession by any number of saints. However, with the Reformation Oren-Magidor argues that though the practice did not become entirely secular, the terminology associated with water cures shifted from religious to medical in nature (147). Their medicinal properties, therefore, were a consequence of “God’s particular divine gift to England…and would work through God’s will,” rather than as a result of saintly intervention or heavenly miracle (147).

At the same time, the vast majority of women continued to rely on ‘kitchen physic,’ or remedies made at home with widely available ingredients. Her examination of this dimension of infertility is intriguing and it best illustrates the connections between religion and medicine in the experience of infertility which she sets out to highlight.

Infertility in Early Modern England convincingly establishes that infertility deserves more thoughtful treatment than it currently receives from scholars, and this book is an important step in that direction. Further, her reminder that the inclusion of religion as fundamental to our understanding of medical explanations of childbearing is a point well taken.

Yet even as Oren-Magidor draws out fascinating elements surrounding infertility she is not always explicit about how those observations are important to her overall argument about the interaction of gender, religion and medicine. Her treatment of magical causes and cures for infertility in “Explaining Infertility” is one such example of this. In the section “Magical Explanations,” she deftly traces the manifestation of magical elements found in medical manuals and in at least one ballad (71-75). However, this discussion would be improved with reference to religious analogues or implications for men and women’s experience of infertility that would justify its inclusion in the book.

Despite its limitations, Infertility in Early Modern England works as an examination of the experience of infertility and offers several jumping off points for further research. Oren-Magidor’s source base is broad, and the inclusion of women’s letters and diaries is particularly refreshing. Women’s voices are often difficult to uncover in this period, especially in medical histories where women’s words were rarely recorded outside of civil and ecclesiastical courts. Those voices make Infertility in Early Modern England worthwhile for experts and general audiences alike.