2019 was an important anniversary year, not only in the history of the United States but also for the genesis of American capitalism.

1619 saw the arrival of the first enslaved Africans in the Virginia colony, marking the beginning of a dark legacy, the impacts of which are still felt in American institutions. The 1619 Project, directed by New York Times reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones, has brought public attention to how slavery and American capitalism grew up together and alongside the global economy.

This conversation has raised uncomfortable questions about contemporary businesses and other institutions. But not for the first time. As Bronwen Everill demonstrates, consumers and businessmen in the late eighteenth- and early nineteenth- centuries also came face to face with the ethical dilemmas of an Atlantic commercial system dependent on enslaved labor.

The questions Americans ask themselves today about ethical consumption in our capitalist society were the same questions abolitionists began to ask as the Atlantic economy developed: Do we have an obligation to participate in moral consumerism? How do we promote public goods in an inherently immoral system while maintaining our humanity? Moreover, how do we reshape our political economy to instill corporate responsibility?

Everill argues that what we call “ethical capitalism” was envisioned by abolitionists in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries who sought to engage with the economy through legitimate commerce and products that were Not Made by Slaves.

In her book, Everill explores how various actors conceptualized solutions to demonstrate the value of “free” labor in the developing global supply chain as well as how they promoted more ethical relationships between production and consumption. Additionally, she highlights the role of West Africa in shaping these ideals, which makes a stark contrast with the “dependency theory” of Africa prevalent in many economic histories.

Though there were many stakeholders loosely bound together by the mutual endorsement of ethical capitalism, this did not lead to a unified vision for undermining enslaved labor, in part, Everill asserts, due to the conflicting motivations of abolitionists. Furthermore, outside influences such as government interference, cultural differences in West African polities, supply and demand dictated by consumers themselves, and the political and economic trends of the era defined engagements with the Atlantic economy and made consistency challenging.

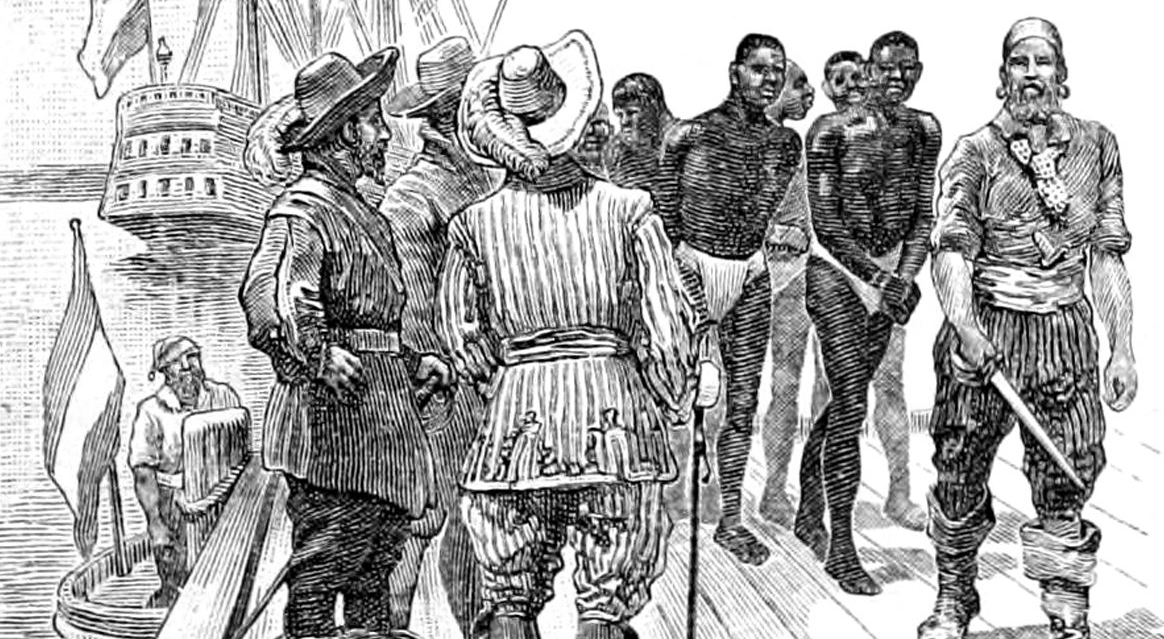

The Slave Trade by Auguste Francois Biard (1833).

Merchants in England, America, and Africa all had an interest in the development of the transatlantic economy, whether they were invested in maintaining production by enslaved labor or not. Everill contends that the tensions and innovations implemented by reformers, who were attempting to “mitigate externalities” and “generate moral outcomes,” framed the principles of ethical capitalism that have persisted in the modern age.

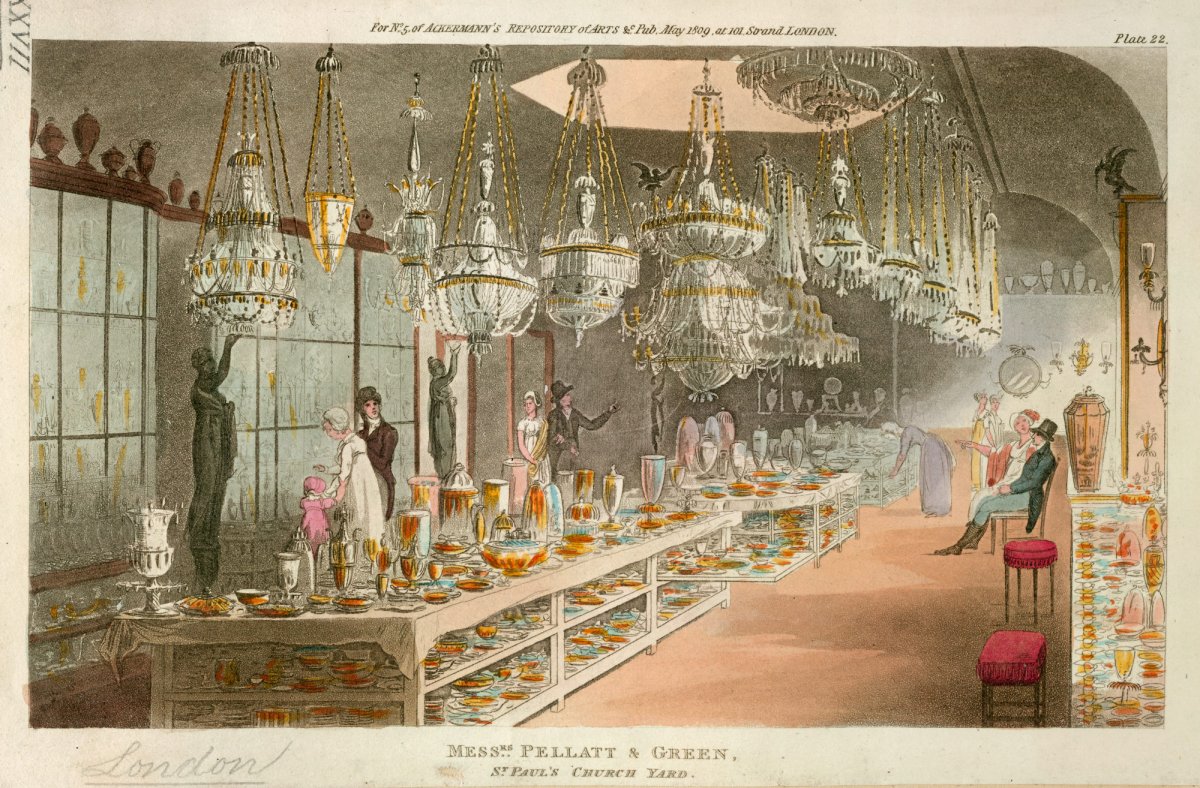

The first two chapters of the book explore the consumer role in driving a more ethical economy. Moral reformers targeted consumers because their consumption essentially relied on the enslavement of Africans. Merchants invested in propagating ethical capitalism did so by promoting “free-produce” and “legitimate commerce,” or in other words goods not produced by enslaved labor or entangled with the slave trade. Everill analyzes the methods by which these reformers identified “ethical commodities” and how they determined what goods were acceptable to trade in Africa.

Interestingly, slavery itself was not often the primary concern of these reformers. West African, British, and American campaigners alike “...were largely focused on the Atlantic trade and its associations with excess.” The advocates for “free-produce” sought to convince buyers that their increased consumption of luxury goods not only supported, but demanded enslaved labor.

Nevertheless, reformers capitalized on how the global economy’s emerging interconnectedness created a space where morality and commerce met, and in turn, publicized campaigns of boycotting and abstention. By placing responsibility on consumers, some reformers were able to make headway with ethical capitalism and ensure profit and consumption while avoiding the slave trade.

The next three chapters of Everill’s study grapple with the movement’s business transactions, delving into issues of fraud, credit, and government relations. Merchants involved in ethical commerce adopted strategies to distinguish “free-produce” goods for the consumer through labeling, imagery, and publications in abolitionist newspapers. These efforts were designed to convince buyers to overlook higher prices for the goods and consider the consumption of ethical products to be a part of their identity.

Abolitionists were also deeply engaged in a debate over credit and fraud. Some argued that credit was necessary to control the market and provide security for legitimate traders; however, more liberal advocates asserted that credit was responsible for expanding slavery in the first place. Creditors continued to operate, calling for governments to intervene and protect their profits, which advanced the interests of American and European firms, but proved to be a disadvantage for African debtors.

Merchants who were peddling legitimate commerce had no shortage of obstacles to overcome. Small victories with credit and fraud were crippled by tariffs that favored the slave labor market. Businessmen used government connections to lobby for non-preferential tariffs to convince consumers and businesses that free-labor produce could be just as profitable. However, Everill writes that “Tariffs created a government-sanctioned monopoly for the West-Indies and empowered slave-trading states in West Africa.”

If abolitionists wanted to win over the market, they had to play by the same rules. They leveraged their networks to participate in Atlantic trade despite the tariffs, though participating in an unethical system led to other questionable business practices. It turned out that abolitionists became responsible for fostering new forms of exploitation.

These labor value and legitimate commerce developments evolved over time, and chapters six and seven look at the implications of newly formed practices and the controversies that shaped changing global producer and consumer relationships.

“Free-produce” might have allowed consumers to continue to enjoy luxury products without the taint of enslaved labor, but the search for free labor did not come without consequences. New conflicts over profitability led those involved with the new trade system to overlook the abuse of foreign workers. The search for ethical capitalism created a new dichotomy of winners and losers, in which most Americans expected the white yeoman farmer to come out on top.

The term “ethical capitalism” as used by Everill in this work poses some problems. Everill accepts slavery and capitalism as two inseparable systems and shows throughout her work that advocates of legitimate commerce were more concerned with their profits rather than the fates of enslaved Africans themselves. Though abolitionists were striving to create a more acceptable system, it certainly was not fully ethical. Personal gain was still an objective, and as Everill admits, there were still losers. The point of her work is well taken, but another term may have been a better fit.

The age of abolition and the controversies that emerged in the development of the global economy helped “free commerce” advocates re-imagine a system that could benefit everyone, resulting in both innovations and inconsistencies. Bronwen Everill has given us an exceptional interpretation of how the Atlantic world envisioned social responsibility and how some people faced questions about ethical capitalism that still vex us today.